20

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ ASSESSMENT IN MANAGING PATIENTS WITH SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

■ NEEDS OF DIFFERENT ASSESSORS

■ TASKS OF THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS

■ SOURCES OF ASSESSMENT INFORMATION

■ SUMMARY

ASSESSMENT IN MANAGING PATIENTS WITH SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Individualized patient assessment is a basic clinical skill and is one of the foundations of quality patient care. As such, it is introduced in the earliest levels of health professional training, and the development of assessment skills is critically evaluated by health educators. Patient assessment can also be an extremely complex and sophisticated clinical or research evaluation involving a multidisciplinary team and multiple forms of patient testing. The importance of assessment in patient evaluation, treatment planning and evolution of the treatment plan, patient safety, and provision of optimal patient care cannot be overstated. Quality assessment bridges the gap between patient diagnosis and the initiation of treatment, ensuring the accuracy of the initial diagnosis and identifying the most effective and efficient care. Patient assessment is as important when dealing with substance use disorders as it is for other medical or psychiatric illnesses.

Addictive disease is a brain disease that when active affects the behavioral control areas. As a consequence, signs and symptoms of active addictive disease are primarily displayed in terms of aberrant, problematic, and atypical behaviors. Contrary to most other diseases, when dealing with addictions, the morbidity of this disease moves from the intrapersonal sense of self (self-image, self-respect, self-concept, sense of self-efficacy, and even psychiatric symptomatology are often the earliest evidence of disease) to interpersonal relationships (family and close friends and then social relationships suffer), to avocations and hobbies, to financial status, to legal standing, to employment or school performance, and finally to physical or end-organ damage. Addictive disease typically affects all of these varied domains of life and is affected in turn by many domains, including legal and licensure status, insurance eligibility, comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions, and family relationships (CSAT TIP #27) (1). This is why the assessment process is such a critical aspect of the approach to addictive disease (2).

NEEDS OF DIFFERENT ASSESSORS

Different clinicians have different clinical decision-making needs when it comes to the initial assessment of substance use disorders, and these different clinicians can be generally divided into four groups: primary care clinicians, addiction medicine or psychiatry specialists, substance use disorder treatment programs, and substance use disorder researchers. Although the use of different levels of assessment may not seem patient centered, the goal is to provide the patient with the right degree of assessment necessary for individualized clinical decision making wherever the patient may access help. Across these settings, assessment is a necessary part of the evaluation of patients with addictive disease and is a critical bridge between screening and diagnosis and treatment planning. There are many tools available to assist in the assessment process. Choosing the right tool for the clinical needs of the patient and the capability of the provider or treatment program can be difficult. The level of staff training and the availability of time and assessment resources (e.g., computerized database access) can all impact on the selection of assessment tools.

Primary Care Assessment Needs and Tools

The primary care provider needs to perform a reasonably brief patient assessment to quickly verify the diagnosis, stage the severity of the disease from the perspective of psychosocial morbidity/end-organ damage/physical dependence, stage the patient’s readiness for behavior change, and screen for immediately important medical or psychiatric comorbidities. This needs to be done in parts of one or more office visits through patient interview, physical examination, use of one or more validated questionnaires or assessment tools, laboratory including toxicology, query of the Pharmacy Monitoring Program (PMP), and, if possible, corroboration in person or by phone from collateral sources (family, friends, other health care providers) after informed consent and release of information for matters related to substance abuse. As is the case for other medical illnesses, different primary care physicians (PCPs) may have different levels of expertise and involvement in the management of addictions. For example, some PCPs may choose more minimal involvement, which would include the ability to identify the substance use disorder, the main substance, severity (e.g., severe/dependent or not), and readiness to change. Others may want to be more closely involved with management or even deliver treatment (e.g., buprenorphine) and coordinate specialty counseling referrals themselves. In that circumstance, more detailed and specific assessments would be necessary.

The primary care practice should utilize a structured approach to this assessment as much as possible to try to ensure an appropriately careful and thorough evaluation. The assessment resources available to the primary care practitioner are limited but quite adequate to perform an addiction assessment. The provider can use and follow up on the results of typically used screening tools like the single screening questions, AUDIT-C, AUDIT, and DAST by eliciting information about patterns of use, adverse consequences of use, possible physiologic dependence, and quantity/frequency of data (included in some screening instruments such as the AUDIT or ASSIST). Screening question responses already provide substantial information and can even be used directly. For example, an AUDIT-C score of 7 or greater substantially increases the probability of alcohol dependence (severe disorder); the frequency of use reported on single-item screeners, AUDIT and AUDIT-C, is likely correlated with severity. And longer questionnaires (e.g., ASSIST) and screening tests recommended decades ago but no longer recommended for screening because they focus only on severe and lifetime disorders (e.g., CAGE/ CAGE-AID, family-CAGE [F-CAGE]) can be useful as brief assessments. This strategy helps with assessing psychosocial morbidity, risk of withdrawal, and need for detoxification and suggests whether or not specialized treatments (e.g., behavioral therapies or pharmacotherapies, some of which can be prescribed by PCPs) might be indicated. In addition, the primary care physician would want to inquire about prior success or failure with abstinence, prior treatment experience, and affiliation with the 12-step or self-help community. Any primary care assessment should include laboratory evaluation including toxicology testing, complete blood count, and liver profile and the use of the pharmacy board Web site or Prescription Monitoring Program if one is available in the practitioner’s state. Assessments should be repeated over time to identify treatment response and needs for changes in strategy. Because of this, assessments that both provide useful information and might be responsive to time and even the target of treatment are particularly useful (e.g., number of heavy drinking days). Brief depression screening is always important, as is a medical history review and review of systems to identify illnesses and symptoms that may be related to substance use. Brief tools can also be used to assess readiness to change. For example, the clinician can ask how ready the patient is to make a change, how important it is to the patients to change, and how confident the patients are that they could change, each on a scale from 1 to 10. The answers can be used to generate discussion toward change (e.g., “why did you say four and not a zero?”).

Addiction Medicine Assessment Needs and Tools

The addiction medicine or psychiatry specialist will approach the assessment from a different perspective. Certainly, assessing the severity of the addictive disease and stage of readiness for behavior change, as well as expert evaluation for medical withdrawal or detoxification needs, must be accomplished. Further evaluation for co-occurring psychiatric disorders, a more thorough family assessment, careful evaluation of all prior assessments and attempts at treatment, patterns of substantial remissions and relapses, and the potential role for pharmacotherapy should all be part of this specialist assessment process.

The addiction medicine or psychiatry physician’s needs, when approaching the assessment process, require much more in-depth evaluation and typically necessitate the use of more formal tools for staging the addictive disease and quantifying the disease severity. The use of the aforementioned screening and brief assessment tools and a more extensive diagnostic interview is required. In addition, formal depression and anxiety screening with tools, such as the Beck Depression Inventory or the Hamilton Anxiety Scale, is often performed. In addition, assessing for new emergence of or change in symptoms of other psychiatric disorders should be performed. Thorough review of prior treatments, length and characteristics of remissions, patterns and triggers for relapse, and current supports and resources available for treatment is essential. Assessment of the readiness for behavior change, of the level of commitment to a recovery program, and of the possibilities for pharmacotherapy are necessary as is careful evaluation for acute, subacute, and postacute withdrawal issues. Interviewing significant others about the patient in order to corroborate the history is even more essential, but still requires informed consent and a release of information for addiction-related information.

Substance Use Disorder Treatment Provider Needs and Tools

The substance use disorder treatment program must spend less time on evaluating patient readiness for behavior change and place more emphasis on prior treatment experiences, identification and management of co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions, family issues and the therapeutic milieu of the living environment, and past relapse patterns (see Chapter 27). The purpose of assessment in this setting extends to details relevant to designing individualized treatment approaches.

The addiction treatment program must use a formalized addiction assessment process for quality control and accreditation reasons. A full medical history and physical exam are mandatory focusing on the aforementioned areas, but a structured interview such as the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) or even the Psychoactive Substance Use Disorders module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (3), or the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM) should also be used. Programs that care for patients with a high prevalence of psychiatric dual diagnosis will utilize the more extensive SCID or at least will need to use specific anxiety and depression screens. Assessing treatment readiness and treatment resistance, as well as relapse patterns and coping skills, is typically a part of the addiction treatment program assessment process. Corroboration of this assessment process is absolutely necessary.

Substance Use Disorder Researcher Needs

The substance use disorder research or evaluation organization has a very different goal when it comes to assessment. The focus tends to be on quantitative evaluation of the degree of accumulated morbidity in the patient’s life, patient-centered research into treatment-matching efforts, identification and exploration of patient characteristics that predict response to treatment, and the elucidation of different types and subtypes of addictive disorders. Well-validated diagnostic tools and measures of change over time, administered in ways that minimize error, are key.

TASKS OF THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS

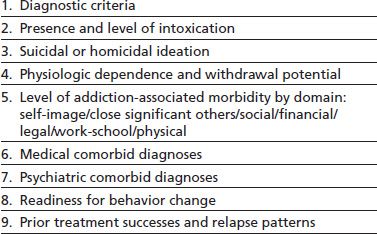

Assessment of substance use disorders within the context of the rest of the patient’s life circumstances is a process that should be utilized when evaluating every patient. The nature of the assessment process is influenced not only by patient factors but by clinician and organizational factors. Therefore, the tools used in an assessment may change depending upon the clinical situation, the skills and resources available to the clinician, and the specific characteristics of patient presentation, but the basic areas to be assessed remain fairly constant as indicated in Table 20-1.

TABLE 20-1 MAJOR AREAS FOR ADDICTION ASSESSMENT

Generally speaking, assessment of a substance use disorder is utilized for one or more of the following tasks: diagnostic verification, assessing for physiologic dependence, staging disease severity, identifying the domains of life affected by the disease, evaluating for additional medical or psychiatric diagnosis, quantifying the disease-associated morbidity, identifying characteristics of the disease that are important from a prognostic or a treatment-matching perspective, quantifying the impact of treatment on disease-associated morbidity, or attempting to determine subtypes of addictive disease.

The assessment process can also be thought about from the perspective of timing. Since 1990, the addiction treatment field has been challenged to improve the pretreatment assessment of alcoholism and other addictions in order to provide better treatment decisions (4). More recently, the concept of intratreatment and even posttreatment assessment has gained favor, urging formal ongoing assessment performed at transition points in the treatment process. This permits the continued adaptation of the treatment plan, a key criterion for most treatment program accreditation reviews (3,5). Pretreatment assessments are focused on identifying the treatment needs of the patient, identifying positive and negative predictive factors for treatment retention, quantifying the pretreatment level of morbidity and impairment of functioning from the addictive disease, and screening for urgent comorbid medical psychiatric and psychosocial issues. It is critical that “pretreatment” assessment not be a barrier to treatment entry (e.g., requirements for hours and hours of assessment before committing to or proceeding with help for the patient). Intratreatment assessment updates should be performed at periodic intervals during the formal treatment and aftercare phase, especially at times of treatment transition or whenever substantial additional or new clinical information becomes available. This intratreatment assessment update should focus on organizing the accumulating data from the treatment experience in such a way as to inform the ongoing treatment planning and patient diagnostic process. This concept, also known as “measurement-based care,” is the norm in the rest of health care (one initiates treatment for hypertension or depression and then assesses response by measuring blood pressure levels and symptoms to determine if treatment is adequate or needs change). Assessments must be used this way in the treatment of addictions; they are only useful to the extent their results are used in treatment decisions. Posttreatment assessment is a bit of a misnomer since the concept that for all with addictions have a start and end date for treatment is antiquated and, again, a foreign concept to the management of chronic illness for other health conditions (e.g., there is no “posttreatment” period for hypertension). Nonetheless, because of the way the addiction treatment system is largely (dis)organized around treatment programs and discrete episodes (not patient illness characteristics and needs), many patients continue to experience discrete episodes of specialized treatment. Assessment at the conclusion of such episodes could be called “posttreatment”—an assessment update performed at the end of formal addiction treatment to summarize the treatment experience, inform aftercare and follow-up monitoring, focus on relapse prevention, reorder the problem list, and focus attention on additional, new, or previously deferred problems. In addition, posttreatment assessment can be used to quantify the patient’s post-treatment level of morbidity and impairment of functioning from addictive disease. The difference between pretreatment and posttreatment assessment can, therefore, quantify and characterize the difference in patient morbidity and thus measure the impact of addiction treatment. “Posttreatment” assessments are now beginning to be recurrent and longitudinal as part of continuing care (that may occur across “program” boundaries according to patient need).

SOURCES OF ASSESSMENT INFORMATION

As domains of patient life affected by addictive disease include such varied areas as intrapersonal, interpersonal, avocations and hobbies, financial status, legal issues, employment or school performance, and physical or end-organ damage, it becomes incumbent on the assessment process to gather information from many different—and at times atypical—sources. This is in contrast to the assessment of most medical or surgical conditions wherein the usual and adequate sources for assessment and management are provided by the initial history and physical followed by laboratory and diagnostic study review.

Sources that commonly are utilized in assessing addictive disease include patient history, physical exam, and laboratory results; toxicology testing; family interview; use of pharmacology (licit and illicit) with special emphasis on the controlled drug use history; legal history questioning, Prescription Monitoring Program data, and educational and occupational interview; and readiness for behavior change evaluation. These areas of questioning and examination are even more important than during routine medical care. Substance use disorders are some of the most highly stigmatized disorders in our society. As a result, issues of the reliability of patient self-report are even more suspect than with other health problems faced by clinicians. It is important to interview patients in ways that avoid defensiveness about the behaviors resulting from their addictive disease. Just as in the area of screening and brief intervention, patient self-report reliability can be improved by using a consistent series of questions that progress from general and open-ended to specific information sought in a more closed-ended question form and by utilizing the family or significant other interview whenever possible.

Owing to high rates of psychiatric symptomatology, a psychiatric screening interview and specific screening for suicidal or homicidal ideation are required. Rates of interpersonal violence are quite high in patients with chemical dependence, either as a child or as an adult, or both, so assessing for physical emotional or sexual abuse history is necessary. Even the cultural background, spiritual inclination, and belief system that the patient holds regarding substance use disorders can be essential areas of assessment. As a consequence, assessment entails extensive patient interview, family interview, checking pharmacy profiles, toxicology testing, documenting legal issues and the actual causes of legal issues, and careful review of prior treatment and relapse experiences. Thus, the assessment process typically is extended in time and multidisciplinary in nature.

ASSESSMENT TOOLS

A thorough assessment should evaluate each area or domain of patient function that is necessary for the needs of the clinician performing or requesting the assessment. As indicated above, typically, the natural history of addictive disease involves progressive dysfunction and disability in the major life domains in a cascade pattern, starting with the interpersonal and eventually progressing to the physical in the later stages. This is why assessment strategies must be sensitive to the natural history of addictive disease. In addition, the assessment tool used should be reliable, reproducible, and verifiable. Diagnostic and assessment strategies are often evaluated based upon their convergent validity (consistency with an established best practice of “gold standard”) and ability to predict different outcomes (predictive validity). A high-quality assessment tool should also have face validity (seems to be clear and logical-, and makes sense), as well as retest and interrater reliability (reoffering the assessment to the same patient by the same or a different staff member should produce a consistent result).

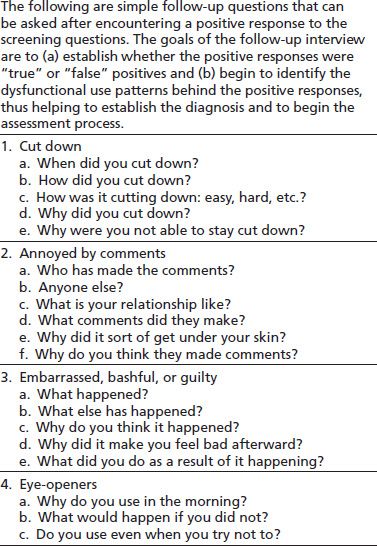

This section suggests tools to assist the clinician in key assessments. The clinician often begins by assessing the severity of the patient’s substance use problem. There are a number of options that vary in the effort required and the range of use they span. The instruments highlighted have been shown to be reliable and valid for the purposes suggested. Some of the tools (like the single screening questions, AUDIT-C, AUDIT, and DAST) are primarily screening tools, but the assessment process is a clear and direct extension of the screening and diagnosis process. As a consequence, extending the use of a screening tool by asking straightforward follow-up questions for each positive screening response can result in a substantial assessment without needing to use additional clinical tools. Table 20-2 demonstrates this process of extending a screening tool for use in assessment. Further information on many of these tools, and other assessment options, can be found online at niaaa.nih.gov/publications, drugabuse.gov, or samsha.gov.

TABLE 20-2 MOVING FROM SCREENING TOOLS TO PATIENT ASSESSMENT

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree