Articulations

CLASSIFICATION OF JOINTS

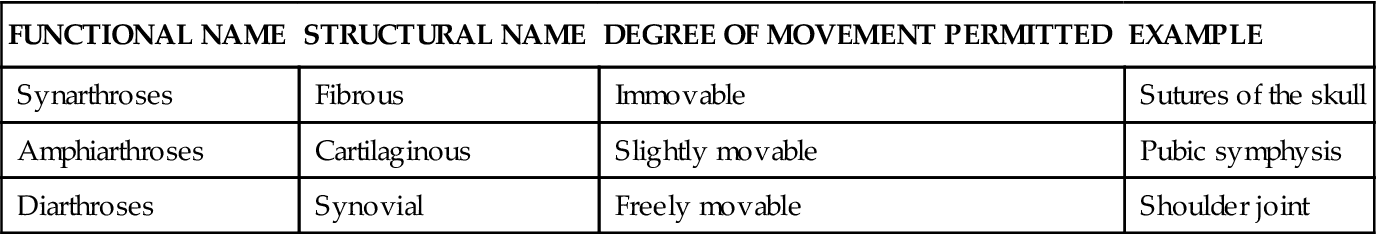

Joints may be classified into three major categories by using a structural or a functional scheme. If a structural classification is used, joints are named according to the type of connective tissue that joins the bones together (fibrous or cartilaginous joints) or by the presence of a fluid-filled joint capsule (synovial joints). If a functional classification scheme is used, joints are divided into three classes according to the degree of movement they permit: synarthroses (immovable), amphiarthroses (slightly movable), and diarthroses (freely movable). Table 10-1 classifies joints according to structure, function, and range of movement. Refer often to this Table and to the illustrations that follow as you read about each of the major joint types in this chapter.

TABLE 10-1

| FUNCTIONAL NAME | STRUCTURAL NAME | DEGREE OF MOVEMENT PERMITTED | EXAMPLE |

| Synarthroses | Fibrous | Immovable | Sutures of the skull |

| Amphiarthroses | Cartilaginous | Slightly movable | Pubic symphysis |

| Diarthroses | Synovial | Freely movable | Shoulder joint |

Fibrous Joints (Synarthroses)

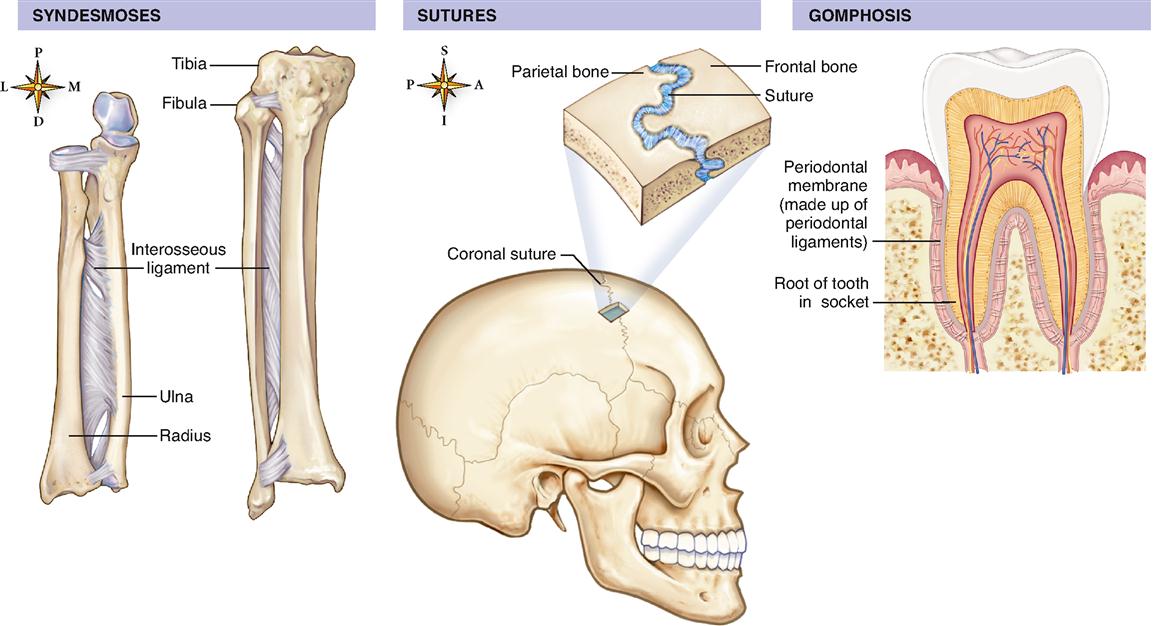

The articulating surfaces of bones that form fibrous joints fit closely together. The different types and amount of connective tissue joining bones in this group may permit very limited movement in some fibrous joints, but most are fixed. There are three subtypes of fibrous joints: syndesmoses, sutures, and gomphoses.

SYNDESMOSES

Syndesmoses (SIN-dez-MO-seez) are joints in which fibrous bands (ligaments) connect two bones. The joint between the distal ends of the radius and ulna is joined by the radioulnar interosseous ligament (Figure 10-1). Although this joint is classified as a fibrous joint, some movement is possible because of ligament flexibility.

SUTURES

Sutures are found only in the skull. In most sutures, teethlike projections jut out from adjacent bones and interlock with each other with only a thin layer of fibrous tissue between them. Sutures become ossified in older adults and form extremely strong lines of fusion between opposing skull bones (see Figure 10-1).

GOMPHOSES

Gomphoses (gom-FOH-seez) are unique joints that occur between the root of a tooth and the alveolar process of the mandible or maxilla (see Figure 10-1). The fibrous tissue between the tooth’s root and the alveolar process is a sheet made up of tiny ligaments and called the periodontal membrane.

Cartilaginous Joints (Amphiarthroses)

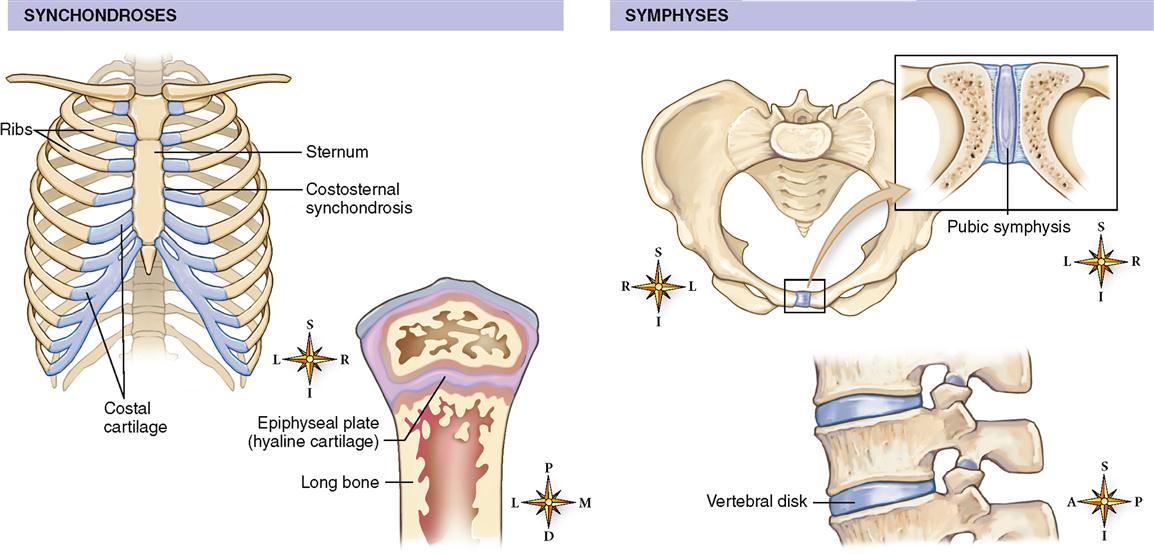

The bones that articulate to form cartilaginous joints are joined together by either hyaline cartilage or fibrocartilage. Joints characterized by the presence of hyaline cartilage between articulating bones are called synchondroses, and those joined by fibrocartilage are called symphyses. Cartilaginous joints permit only very limited movement between articulating bones in certain circumstances. During childbirth, for example, slight movement at the pubic symphysis facilitates the baby’s passage through the pelvis.

SYNCHONDROSES

Note that joints identified as synchondroses (SIN-kon-DROH-seez) have hyaline cartilage between articulating bones. One example of a synchondrosis is the joint between the sphenoid bone and the occipital bone (see Figure 9-4 on p. 229). Another commonly cited example is the articulation between the first rib and sternum (a costosternal synchondrosis; Figure 10-2). Some anatomists, however, prefer to classify this joint as a special kind of synarthrosis. All other sternocostal joints are synovial joints, even though they often lack joint capsules.

The best example of a synchondrosis is the joint present during the growth years between the epiphyses of a long bone and its diaphysis (see Figure 10-2). The epiphyseal plate between the epiphysis and diaphyses of a long bone is a temporary synchondrosis that normally does not move. The plate of hyaline cartilage is totally replaced by bone at skeletal maturity. Most synchondroses are present only in the immature skeleton as epiphyseal plates—they eventually disappear as the bones fuse together.

SYMPHYSES

A symphysis (SIM-fi-sis) is a joint in which a pad or disk of fibrocartilage connects two bones. The tough fibrocartilage disks in these joints may permit slight movement when pressure is applied between the bones.

Most symphyses are located in the midline of the body. Examples of symphyses include the pubic symphysis and the articulation between the bodies of adjacent vertebrae (see Figure 10-2). The intervertebral disk in these joints is composed of tough and resilient fibrocartilage that absorbs shock and permits limited movement. The bones of the vertebral column have numerous points of articulation between them. Collectively, these joints permit limited motion of the spine in a very restricted range. The articulation between the bodies of adjacent vertebrae is classified as a cartilaginous joint. The points of contact between the articular facets of adjacent vertebrae are, however, considered synovial joints and are described later in the chapter.

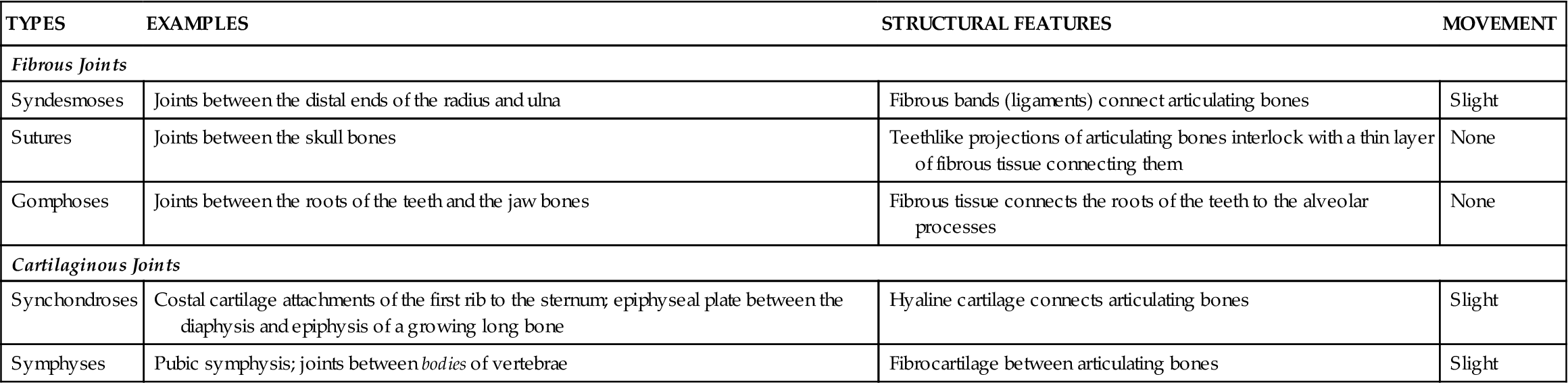

Table 10-2 summarizes the different kinds of fibrous and cartilaginous joints.

TABLE 10-2

Classification of Fibrous and Cartilaginous Joints

| TYPES | EXAMPLES | STRUCTURAL FEATURES | MOVEMENT |

| Fibrous Joints | |||

| Syndesmoses | Joints between the distal ends of the radius and ulna | Fibrous bands (ligaments) connect articulating bones | Slight |

| Sutures | Joints between the skull bones | Teethlike projections of articulating bones interlock with a thin layer of fibrous tissue connecting them | None |

| Gomphoses | Joints between the roots of the teeth and the jaw bones | Fibrous tissue connects the roots of the teeth to the alveolar processes | None |

| Cartilaginous Joints | |||

| Synchondroses | Costal cartilage attachments of the first rib to the sternum; epiphyseal plate between the diaphysis and epiphysis of a growing long bone | Hyaline cartilage connects articulating bones | Slight |

| Symphyses | Pubic symphysis; joints between bodies of vertebrae | Fibrocartilage between articulating bones | Slight |

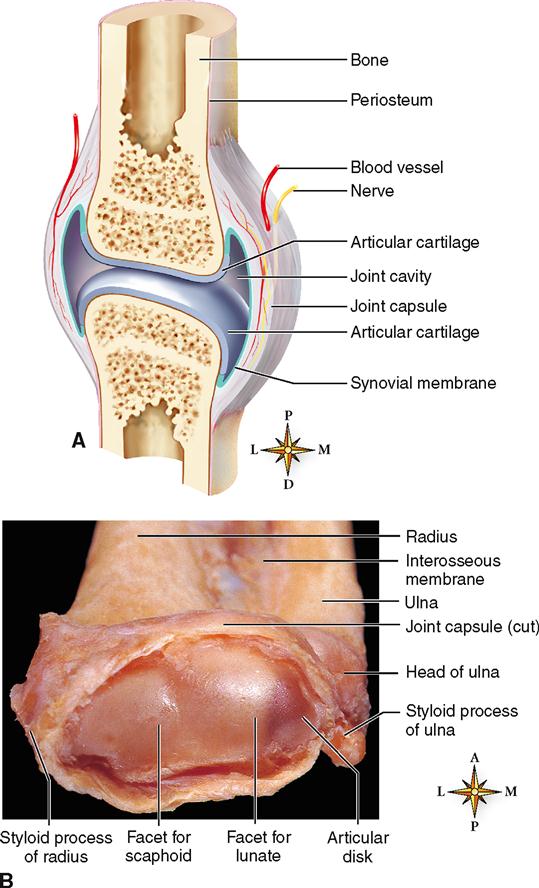

Synovial Joints (Diarthroses)

Synovial joints are freely movable joints. They are not only the body’s most mobile but also its most numerous and anatomically most complex joints. A majority of the joints between bones in the appendicular skeleton are synovial joints.

STRUCTURE OF SYNOVIAL JOINTS

The following seven structures characterize synovial, or freely movable, joints (Figure 10-3):

5. Menisci (articular disks). Pads of fibrocartilage located between the articulating ends of bones in some diarthroses. Usually these pads divide the joint cavity into two separate cavities. The knee joint contains two menisci (see Figure 10-10).

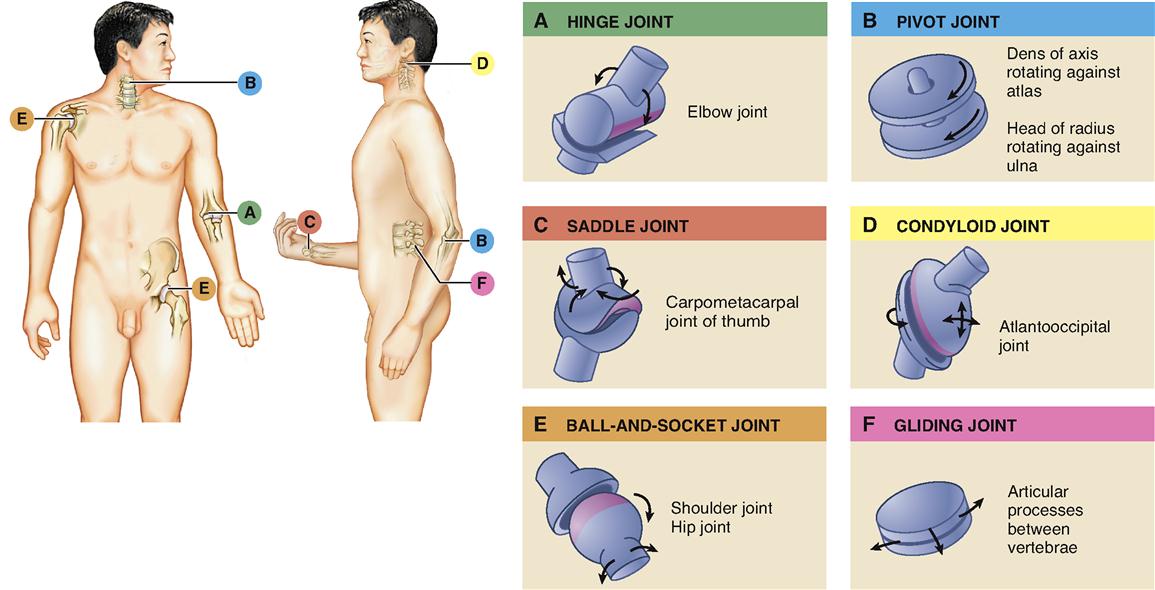

TYPES OF SYNOVIAL JOINTS

Synovial joints are divided into three main groups: uniaxial, biaxial, and multiaxial. Each is subdivided further into two subtypes as follows:

1. Uniaxial joints. Synovial joints that permit movement around only one axis and in only one plane. Hinge and pivot joints are types of uniaxial joints (Figure 10-4, A and B).

a. Hinge joints. Those in which the articulating ends of the bones form a hinge-shaped unit. Like a common door hinge, hinge joints permit only back-and-forth movements, namely, flexion and extension. If you have access to an articulated skeleton, examine the articulating end of the humerus (the trochlea) and the ulna (the semilunar notch). Observe their interaction as you flex and extend the forearm. Do you see why you can flex and extend your forearm but cannot move it in any other way at this joint? The shapes of the trochlea and the semilunar notch (see Figure 9-18, p. 252, and Figure 9-19, p. 253) permit only the uniaxial, horizontal-plane movements of flexion and extension at the elbow. Other hinge joints include the knee and interphalangeal joints.

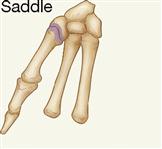

2. Biaxial joints. Diarthroses that permit movement around two perpendicular axes in two perpendicular planes. Saddle and condyloid joints are types of biaxial joints (Figure 10-4, C and D).

3. Multiaxial joints. Joints that permit movement around three or more axes and in three or more planes (Figure 10-4, E and F).

Table 10-3 summarizes the classes of synovial joints.

TABLE 10-3

Classification of Synovial Joints

| TYPES | EXAMPLES | STRUCTURE | MOVEMENT |

| Uniaxial | Around one axis; in one place | ||

| Elbow joint | Spool-shaped process fits into a concave socket | Flexion and extension only |

| Joint between the first and second cervical vertebrae | Arch-shaped process fits around a peglike process | Rotation |

| Biaxial | Around two axes, perpendicular to each other; in two planes | ||

|