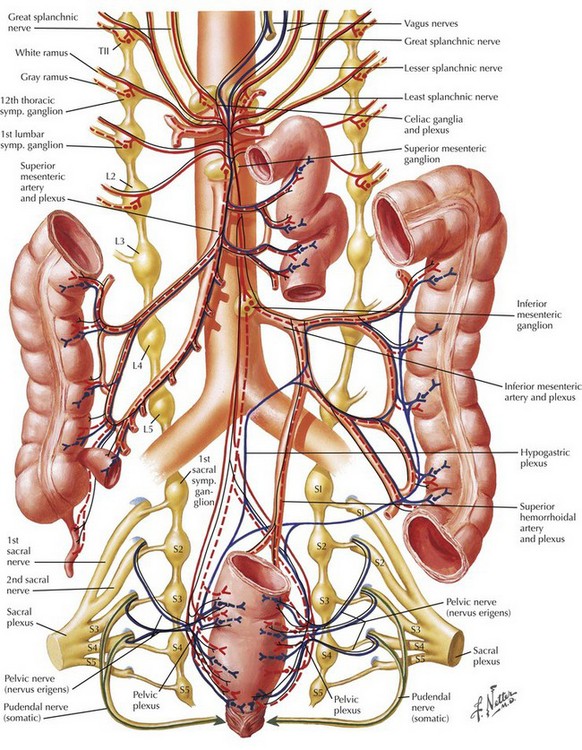

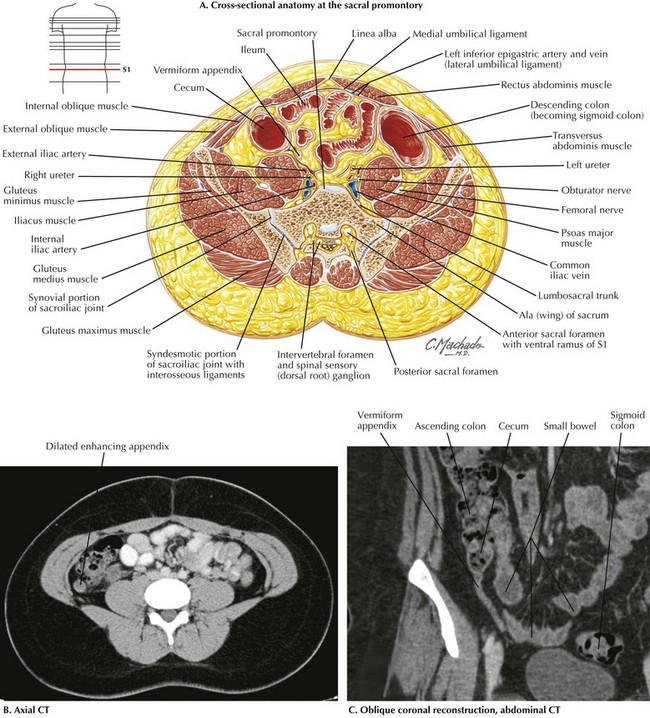

Chapter 19 There is considerable variation in the clinical presentation of appendicitis. The classic patient presents with several hours of periumbilical pain that “migrates” to the right lower abdomen, with associated anorexia. The migration of the pain is mediated by the separate innervation of visceral and parietal tissues. Appendiceal obstruction and inflammation, which occur early in the process, cause irritation of autonomic visceral afferent nerves of the superior mesenteric ganglion that result in a nonspecific, poorly localized epigastric or periumbilical pain, secondary to the location and lack of specificity of the autonomic ganglion (Fig. 19-1). Ileus, nausea, anorexia, and diarrhea may also be mediated in this manner. Once inflammation reaches parietal surfaces of the peritoneum (e.g., through perforation), somatic sensory fibers create localized pain in the right lower quadrant (RLQ) with findings of peritonitis, including rigidity, distention, and hyperesthesia. Examination of the patient with appendicitis may further localize inflammation and determine the stage of the diagnosis. Tenderness in the RLQ at McBurney’s point is typical. Well-recognized signs include RLQ pain on palpation of the left abdomen (Rovsing’s sign) and internal rotation of the right hip resulting in motion of deep pelvic musculature, which can cause pain in the case of pelvic appendicitis (obturator sign). Pain with extension of the right hip is caused by motion of the psoas muscle posterior to the cecum (psoas sign) (Fig. 19-2, A). FIGURE 19–2 Cross-sectional periappendicular anatomy. Although the diagnosis of appendicitis may often be made with physical examination alone, computed tomography (CT) has been increasingly used for the evaluation of patients with appendiceal pathology because of its high sensitivity and specificity. Coronal and sagittal reconstructions provide excellent anatomic detail that is useful in surgical planning (Fig. 19-2, B and C).

Appendectomy

Anatomic Principles of Diagnosis and Evaluation

CT, Computed tomography; S1, 1st sacral vertebra.

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine