Whenever the anatomy of the anal canal is discussed, one visible landmark, namely the dentate or pectinate line, is mentioned as important. This line is located at the distal end of the anal columns where the anal valves are situated. It has also been called the mucocutaneous line, although it is separated from the perianal skin by the distal most anal canal. The lymphatic drainage proximal to the dentate line is to the internal iliac nodes and the blood supply is from the superior rectal artery, whereas below the line, the lymphatic drainage is to the superficial inguinal nodes and the blood supply is from the inferior rectal artery. When the upper margin of the anal canal is defined as the level of insertion of the levator ani muscle, part of the external anal sphincter, then most of the proximal-most anal canal is lined by the distal-most rectal columnar mucosa (2).

At flexible sigmoidoscopic or colonoscopic examination, the anal mucosa is often difficult to visualize because the endoscope quickly slips through the anal canal into the wider and longer rectum. The best views of the anus are obtained either on retroflex examination with a flexible endoscope or by using a rigid anoscope. However, subtle alterations in anal mucosal architecture, some of which are neoplasms, may be missed unless the endoscopic procedure is directed toward a detailed anal examination.

Histologically, when the anus is defined as everything surrounded by the sphincter muscles, it is divided into three zones: an upper or proximal colorectal zone, a middle anal transitional zone (ATZ), and a lower or distal squamous zone (3). The colorectal zone mucosa is similar to rectal mucosa; however, compared to the more proximal rectal mucosa, the crypts are normally shorter and more irregular in shape and orientation, and the lamina propria may contain more smooth muscle fibers that extend upward from the muscularis mucosae. These normal findings should not be interpreted as evidence of inactive chronic inflammation because they may be nothing more than the consequence of chronic physiologic prolapse of the most distal columnar mucosa.

Diseases in this proximal columnar zone are indistinguishable from those occurring in the rectum. Thus, for example, adenocarcinomas arising here are identical to colorectal carcinomas, and they should be included with the colorectal neoplasms rather than making them a specific type of anal canal carcinoma. However, some studies, such as the national cancer database report, include these adenocarcinomas in the category of anal neoplasms, thus confusing the data and making comparative analyses difficult (4). When diseases of the anus are discussed in pathology journals or textbooks, only those indigenous to the transitional and squamous zones are included. Diseases of the rectal mucosa that overlie the sphincter muscles are considered to be colorectal diseases.

Remember that the dentate line is a circumferential line that is located at the level of the anal valves. It is remarkable how many clinicians, both gastroenterologists and surgeons, mistakenly think that the dentate line is more proximal at the level of the junction between the rectal columnar mucosa and the ATZ. The ATZ extends upward from the dentate line for variable distances (from barely discernible to 2 cm in different specimens) to join the colorectal zone. It may contain a variety of epithelia (Fig. 39.1). The most typical variant (“ATZ epithelium”) is four to nine cells thick and is composed of relatively small cells surmounted by a layer of cuboidal, polygonal, or mucinous columnar cells. This epithelium has features of both metaplastic squamous mucosa and of urothelium (3,5). The ATZ may also contain colorectal crypts (especially in its upper part) and areas of mature squamous epithelium. Endocrine cells and melanocytes are also normal epithelial constituents (6). The melanocytes are most numerous in the distal squamous zone, rare in the ATZ, and not present in the colorectal zone (7). However, in patients with anal melanomas, melanocytes have also been found in the colorectal zone. Six to eight anal glands or ducts extend from the ATZ into the submucosa. Some extend perpendicularly deeply toward the internal anal sphincter which they may actually penetrate (3), whereas others extend distally or proximally beneath the anal epithelium. Some of these are lined by multilayered epithelium identical to anal transitional epithelium, whereas others have epithelium resembling tubal epithelium, usually without cilia, and still others have goblet cells and look colorectal. In men, they may occasionally end in prostatic epithelium.

The distal squamous zone, also known as the pectinate zone, has a nonkeratinized squamous epithelium with scattered melanocytes but without ducts or glands. It merges distally with perianal skin, the latter characterized by keratinization of the squamous epithelium and by the presence of hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands, mostly apocrine glands (1).

Although these epithelial types generally occur in the specific gross zones, they are not totally predictable. In some anuses, the transitional epithelium may cover only a few millimeters of the ATZ, whereas in others, its length may be much greater. It is not unusual for there to be areas where squamous, rather than transitional, epithelium abuts the rectal columnar mucosa.

The subepithelial stroma of the anal canal, sometimes referred to as the submucosa, is loose collagenous and contains small smooth muscle bundles, nerves, and vessels. Multinucleated stromal cells, peculiar fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts are common and should not be confused with neoplastic cells (8). The reader is referred to the standard anatomy textbooks for a discussion of the vasculature and innervation of the anal canal.

NONNEOPLASTIC DISEASES INTRINSIC TO THE ANUS

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES

Embryologic abnormalities involving the anal canal occur in approximately 1 in 5000 births and include stenosis and absence of the anal canal, imperforate anus, fistulae, and anorectal duplications and cysts (1,9). Some of these conditions, as well as Hirschsprung disease (aganglionic megacolon, which is not really an anal disease but a distal rectal disease), are discussed in the chapter “Nonneoplastic Intestinal Diseases.” In the evaluation of patients suspected of having Hirschsprung disease, it should be remembered that ganglion cells are normally absent or sparse in the distal most rectum for at least 1 to 2 cm above the anorectal junction (1,10). Therefore, biopsies performed to detect ganglion cells in the submucosal plexus should always be taken from above this zone.

HEMORRHOIDS

If there is deterioration of the connective tissue, including the smooth muscle that normally anchors the anal submucosal vascular channels known as veins or sinusoids, these vessels may enlarge, develop thick walls, and then prolapse to form hemorrhoids. Bleeding is the major sign of hemorrhoids; pain occurs only when they are strangulated and thrombosed (11). Portal hypertension is not associated with an increased prevalence of hemorrhoids but, rather, with more severe hemorrhoidal bleeding related to elevated portal venous pressure and, possibly, defects in coagulation (1,12).

Prolapsed or thrombosed hemorrhoids may be resected. Microscopically, excision specimens contain dilated, thick-walled submucosal vessels and sinusoidal spaces, often with thrombi and adjacent old hemorrhage with stromal hemosiderin. The surface epithelium varies depending on the site of origin of the hemorrhoid within the anal canal; thus, it may be colorectal, ATZ type, or squamous, and it is frequently ulcerated (11).

All tissues excised as clinical hemorrhoids should be examined histologically. Hemorrhoids are common, but any anal neoplasm may present clinically as a hemorrhoid. Furthermore, the ATZ and squamous epithelium covering the hemorrhoids may contain flat or papillary condylomata, a variety of squamous hyperplasias and the whole gamut of intraepithelial neoplasias, and even invasive carcinoma (see “Neoplasms Intrinsic to the Anus”). The stroma may contain unexpectedly florid inflammation that may raise the possibility of infections, including those that are granulomatous, or Crohn disease (1,9,11). An inflammatory infiltrate rich in plasma cells may suggest syphilis.

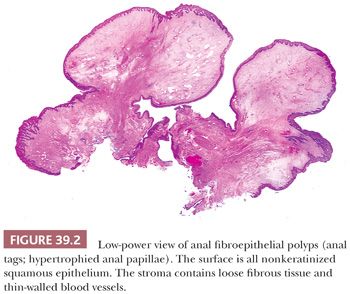

ANAL TAGS, PAPILLAE, AND FIBROEPITHELIAL POLYPS

Anal tags, also known as fibroepithelial polyps, are projections of submucosa and overlying mucosa, the latter usually squamous. The submucosa contains loose fibrous tissue with scattered blood vessels that is characteristic of anal submucosa in general. However, some anal tags contain the same large, multinucleated, stellate-shaped fibroblasts and myofibroblasts as are normally found in the anal stroma, but they may be more numerous and larger (8). These tags often have the clinical appearance of hemorrhoids, so they are usually resected and submitted to the pathologist as hemorrhoids; however, they do not contain dilated thick-walled varices or any old hemorrhage. They are identical to cutaneous acrochordons and may be the same as some forms of hypertrophied anal papillae (13,14) (Fig. 39.2).

INFLAMMATORY CLOACOGENIC POLYPS

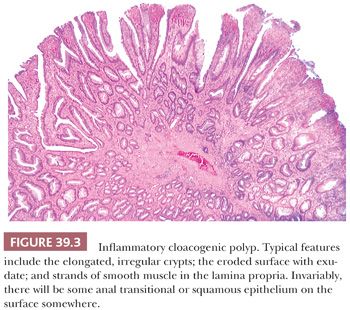

Inflammatory cloacogenic polyps (ICPs) occur predominantly in middle-aged patients whose most common complaint is rectal bleeding of variable (but often lengthy) duration. The polyps, which are located within the anal canal at the junction of the distal rectal and ATZs, are single or multiple, generally about 1 to 2 cm in range, and sessile. Thus, they clinically and grossly mimic hemorrhoids and are usually resected because they are diagnosed as hemorrhoids (15,16). The pathogenesis is presumably prolapse with subsequent damage and repair. They also have been described in two patients with Crohn disease (but without documented anal involvement by the Crohn disease) and distal to one rectal carcinoma. However, the ICPs are generally unrelated to the other diseases. Simple excision is usually curative (15).

Histologically, the features of ICPs are variable (Fig. 39.3). They straddle the junction between the distal rectal columnar mucosa and the anal transitional or squamous mucosa. As a result, the epithelium is a mixture of rectal columnar and anal squamous and transitional zone epithelia. Some ICPs have a predominantly tubular, villous, or mixed architecture. When there is a villiform surface, commonly, the tips of the villi are eroded and covered by exudates. The crypts are longer than normal, distorted with branching and budding, and some crypts have a serrated luminal contour. We have seen some ICPs with prominent serrated crypts misdiagnosed as hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. In some ICPs, some of the basal crypts extend into the submucosa as small, mucus-filled cysts, an appearance identical to colitis cystica profunda. The columnar epithelium lining the crypts and cysts and covering the surface may be regenerative or hyperplastic, so much so that there may be areas that mimic adenomas. The muscularis mucosae is thickened and irregular, frequently extending as muscular strands high into the lamina propria, often accompanied by collagen fibers and small vessels. In those polyps with the most muscle, the basal crypts may be squeezed by the muscle bundles, resulting in pointed ends to the crypts, the diamond-shaped crypts of prolapse. Some ICPs are therefore identical to colorectal polypoid mucosal prolapse, such as in the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome and cap polyposis. In some cases, it may be almost impossible to tell them apart. Because of the combination of villi and hyperplastic columnar epithelium, ICPs may superficially resemble villous adenomas (15,16). However, these lesions should not be misdiagnosed as colorectal-type adenomas, and the submucosal cystic crypts should not be misinterpreted as invasive carcinoma. Recognition of the benign epithelial nuclear cytology, the lack of desmoplasia, the fibromuscular lamina propria, the mixture of colorectal and ATZ and/or squamous epithelia, and the typically eroded villiform surface of ICP should eliminate diagnostic errors.

FISSURES AND FISTULAE

Anal fissures are common posttraumatic lesions, typically located posteriorly in the midline (9). Anal fistulae are also common and usually develop secondary to chronic infection of the anal glands or ducts. Many are idiopathic but they are also frequent in patients with Crohn disease and in occasional patients with ulcerative colitis. On microscopic examination, specimens from fistulae contain a central core of active and chronic inflammation with granulation tissue, possibly with foreign body giant cells, surrounded by scar. Occasionally, granulomas are present. Squamous or ATZ epithelium may extend into the tract and partially epithelialize it.

CROHN DISEASE

In Crohn disease (CD), the anal canal is involved in patients with small intestinal and/or colonic disease (17). The anal findings in CD are varied and include fissures, fistulae, ulcers, abscesses, and tags. Anal involvement may be the first manifestation of CD. Very rare malignant complications have been reported (see the section “Adenocarcinoma”) (17–21).

In CD, the most characteristic finding is the nonnecrotic granuloma that may contain multinucleated giant cells. From a practical standpoint, the diagnosis of CD cannot be made on a biopsy of an anal fissure, fistula, or inflammatory polyp that contains granulomas, unless the patient has known CD elsewhere. However, CD can be suspected if an anal biopsy contains small, tight, nonnecrotizing granulomas close to the mucosa, especially in a young person with no other explanation for fissures or fistulae. Patients with disseminated tuberculosis may also have anal disease with granulomas. Remember that infectious granulomatous diseases, such as tuberculosis and histoplasmosis can also involve the anal canal, but such granulomas are commonly necrotizing (9).

ULCERATIVE COLITIS

Ulcerative colitis commonly involves the distal-most rectal mucosa that is surrounded by the proximal end of the anal sphincter musculature, but we do not think of this as anal involvement. Nevertheless, in rare patients with ulcerative colitis, chronic inflammation extends distally to involve the anal transitional and squamous mucosae with plasma cells and even lymphoid follicles in the stroma and various types of injuries to the epithelium, including spongiosis and lymphocytic transmigration. None of this is specific for ulcerative colitis, and it is not clear whether this inflammation is even a part of ulcerative colitis or secondary to irritation from the severe diarrhea that many of these patients have. This also occurs in patients who have had total colectomies with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. In such cases, biopsies of the rectal cuff occasionally will also capture some anal canal epithelium with underlying chronic inflammation.

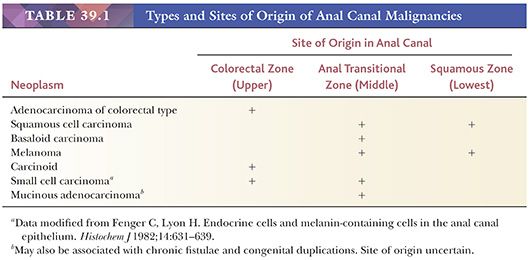

NEOPLASMS INTRINSIC TO THE ANUS

Although uncommon, malignancies of the anal canal encompass a complex array of neoplasms (Table 39.1). The most confusing groups in terms of nomenclature have been the tumors arising from the surface epithelium of the ATZ and distal squamous mucosa, which have been variously categorized as “squamous,” “basaloid,” “cloacogenic,” and “transitional.” The World Health Organization recognizes the following anal carcinomas: squamous cell, verrucous, undifferentiated, adenocarcinoma (arising in mucosa, extramucosal, within anorectal fistulae, and of anal glands), mucinous adenocarcinoma, and the usual variety of neuroendocrine neoplasms that seem to occur everywhere (22). Verrucous carcinomas include what used to be called giant condylomas of Buschke and Lowenstein, regardless of their lack of significant keratinization. The reader is referred to previously published reviews for further discussion of these various categories (3,9,22,23).

SURFACE EPITHELIAL CARCINOMAS OF THE ANAL TRANSITIONAL ZONE AND SQUAMOUS ZONE

In this chapter, according to current terminology, all these carcinomas of the anal canal are variants of squamous cell carcinoma. The formerly accepted terms such as cloacogenic and transitional are no longer used. Many of these carcinomas have mixed histologic features with different cell types, and classification as to predominant cell type may be subjective and is dependent on the extent of tissue sampling (24). In fact, reproducibility among even experienced pathologists in recognizing specific subtypes is poor (25). Furthermore, recent studies indicate that all the carcinomas, regardless of major cell type, have the same association with human papillomavirus (HPV). Finally, although earlier studies suggested differences in prognosis between patients with the basaloid type of carcinoma when compared to those with more traditional squamous cell carcinoma, recent large series have demonstrated that, in general, the histologic features of the tumor are not of clinical significance (22,26).

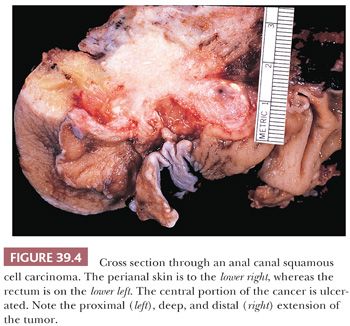

Squamous cell carcinomas of the anal canal, which account for 1% to 2% of all colonic and anal malignancies (27–29), have increased in incidence in Western countries over the past 30 years. They occur chiefly in middle-aged patients with a marked female predominance that varies from 5:1 to 3:2, depending on the population studied (3,23,24,27,30–32). There has also been an increased incidence in male homosexual patients. Rectal bleeding is the most common presenting feature, followed by anorectal pain or a mass (18,24,27).

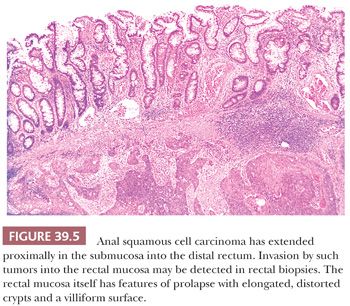

Grossly, the carcinomas are typically nodular and/or ulcerated. Unfortunately, most are large (more than 3 to 4 cm in diameter) when first diagnosed (24). They invade deeply into the wall and spread distally and proximally. Some cancers extend proximally in the submucosa beneath the rectal columnar mucosa and invade that mucosa, producing an erosion, ulcer, or polypoid projection proximal to the primary site of the carcinoma in the more distal ATZ or squamous zone (Figs. 39.4 and 39.5).

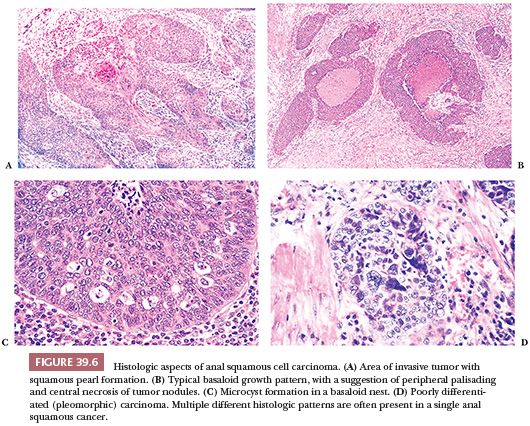

The histologic features are variable (Fig. 39.6). There are two dominant cell types and growth patterns. The first type is focally keratinizing differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with various degrees of pleomorphism, which resembles invasive squamous cell carcinomas in other body sites. The second type, the basaloid, has nests of small, crowded, undifferentiated cells resembling cutaneous basal carcinoma cells, with focal, generally imperfect, palisading of nuclei at the edges of the nests. The center of these nests often contains tiny foci of keratinization and/or foci of granular necrosis. On occasions, basaloid nests in biopsies, especially biopsies from the distal rectum, mimic nests of carcinoid tumor or even melanoma (33). Appropriate immunostains will help to make the correct diagnosis. The basaloid pattern can be distinguished from upward extension of basal cell carcinoma originating in perianal skin because of the necrosis, the generally larger cells of the basaloid carcinoma, its more numerous mitoses, and its more flagrant invasive growth pattern (3). Also, basal cell carcinomas have the characteristic basophilic desmoplastic stroma that is seen in identical tumors of the skin. In some anal carcinomas, there are equal squamous and basaloid components. Occasional tumors are composed mostly of squamous carcinoma with scattered mucin cells or small, mucin-filled cysts, so that, to a limited degree, they may resemble mucoepidermoid tumors of salivary gland origin (3,23,29). Finally, there are tumors that contain all or a large variety of patterns. Common to all types are scattered holes or microcysts within the nests that do not contain anything.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree