Chapter 49 It is important to understand that psychosis is not a disease. Psychosis is the term that is used to describe a general symptom complex in which gross impairment of reality is demonstrated. It has many causes—both organic and psychiatric. Box 49-1 lists symptoms that are commonly associated with the presentation of a clinical psychosis. Table 49-1 shows the most common medical disorders that may present with psychiatric symptoms, but not all of these represent psychotic symptoms. A large number of diverse and even common medications can cause psychotic symptoms (Table 49-2). Table 49-3 lists different psychiatric disorders that may present with psychosis. Therefore, it is difficult to talk about treating the general symptoms of psychosis; it is more productive to talk about specific psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. TABLE 49-1 Medical Conditions Associated with Psychiatric Symptoms Modified from Gabbard GO: Gabbard’s treatment of psychiatric disorders,ed 4, New York, 2007, American Psychiatric Publishing. TABLE 49-2 Medications That Can Cause Psychotic Symptoms Acyclovir Amantadine Amphetamine-like drugs Anabolic steroids Anticholinergics and atropine Anticonvulsants Antidepressants, all Baclofen Barbiturates Benzodiazepines α-Adrenergic blockers Calcium channel blockers Cephalosporins Corticosteroids Dopamine receptor agonists fluoroquinolone antibiotics Histamine H1-receptor blockers Histamine H2-receptor blockers HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) NSAIDs Opioids Procaine derivatives Salicylates Sulfonamides Data from The Medical Letter: Some drugs that cause psychiatric symptoms, Med Lett 44:1134, 2002, and Gabbard GO: Gabbard’s treatment of psychiatric disorders, ed 4, New York, 2007, American Psychiatric Publishing. TABLE 49-3 Psychiatric Disorders That May Present with Psychosis Modified from Stern TA et al: Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry,ed 5, St Louis, 2004, Mosby. Schizophrenia is diagnosed by history after the patient is assessed in three areas: 1. Characteristic symptoms: Two of more of the following: 2. Social or occupational dysfunction, notably problems with work, school, interpersonal relations, or self-care 1. Has a reversible organic or substance-induced cause of psychosis been ruled out? 2. Are cognitive deficits prominent? (i.e., delirium or dementia) 3. Is the psychotic illness continuous or episodic? Have psychotic symptoms (active phase) been present for at least 4 weeks? Has evidence of the illness been present for at least 6 months? Is a decline in level of functioning evident? Are negative symptoms present? 4. Are mood episodes prominent? Have episodes of major depression or mania occurred? Do psychotic features occur only during affective episodes? The exact mechanism of antipsychotic drug action is unknown. These drugs are thought to work by blocking postsynaptic dopamine receptors in the hypothalamus, basal ganglia, limbic system, brainstem, and medulla, and to some extent serotonin receptors. Much work has been done to elucidate which receptors each drug affects. How this receptor blocking causes specific changes in behavior and cognition is not known. See Table 49-4 for specific neurotransmitter-receptor blocking actions of individual medications. Each neurotransmitter is associated with specific side effects. However, the correlation between the two is not completely understood. A very complicated and overlapping set of mechanisms interact to produce a wide variety of effects. Another complication is that these drugs produce different effects from patient to patient. Most cause sedation in some people and agitation in others (Box 49-2). Some antipsychotic drugs cause metabolic side effects such as obesity and diabetes by activating the SMAD3 protein, which plays a role in the transforming growth factor beta pathway—a cellular mechanism responsible for inflammation and insulin signaling, among other processes. TABLE 49-4 Comparison of Mechanism of Action and Associated Adverse Reactions

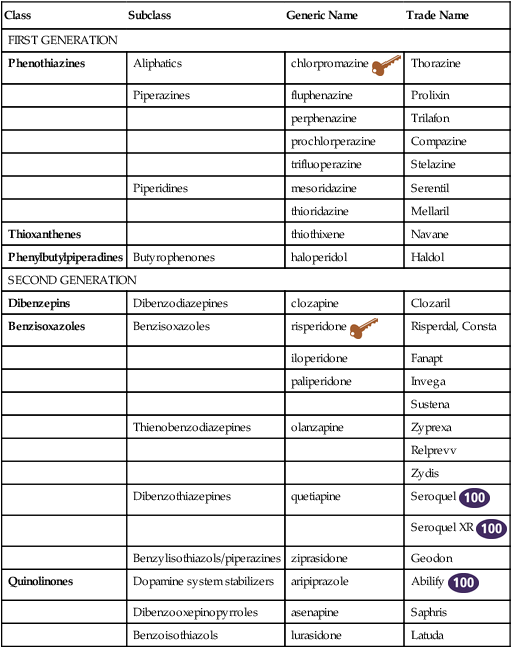

Antipsychotics

Class

Subclass

Generic Name

Trade Name

FIRST GENERATION

Phenothiazines

Aliphatics

chlorpromazine ![]()

Thorazine

Piperazines

fluphenazine

Prolixin

perphenazine

Trilafon

prochlorperazine

Compazine

trifluoperazine

Stelazine

Piperidines

mesoridazine

Serentil

thioridazine

Mellaril

Thioxanthenes

thiothixene

Navane

Phenylbutylpiperadines

Butyrophenones

haloperidol

Haldol

SECOND GENERATION

Dibenzepins

Dibenzodiazepines

clozapine

Clozaril

Benzisoxazoles

Benzisoxazoles

risperidone ![]()

Risperdal, Consta

iloperidone

Fanapt

paliperidone

Invega

Sustena

Thienobenzodiazepines

olanzapine

Zyprexa

Relprevv

Zydis

Dibenzothiazepines

quetiapine

Seroquel ![]()

Seroquel XR ![]()

Benzylisothiazols/piperazines

ziprasidone

Geodon

Quinolinones

Dopamine system stabilizers

aripiprazole

Abilify ![]()

Dibenzooxepinopyrroles

asenapine

Saphris

Benzoisothiazols

lurasidone

Latuda

![]() Top 100 Icon;

Top 100 Icon; ![]() key drug. Key drug selected because it was the first and is still in use.

key drug. Key drug selected because it was the first and is still in use.

Therapeutic Overview

Causes

Example

Metabolic and endocrine

Addison’s disease

Calcium imbalance

Carcinoid syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome

Electrolyte abnormalities

Hepatic failure

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperthyroidism

Hypoglycemia

Hypothyroidism

Hypoxia

Magnesium imbalance

Pheochromocytoma

Porphyria

Renal failure

Serotonin syndrome

Wilson’s disease

Electrical

Complex partial seizures

Peri-ictal states (depression, hallucinations)

Postictal states (depression, dissociation, or disinhibition)

Temporal lobe status epilepticus

Neoplastic

Carcinoid syndrome

Carcinoma of the pancreas

Metastatic brain tumors

Primary brain tumor

Remote effects of carcinoma

Arterial

Arteriovenous malformations

Hypertensive lacunar state

Inflammation (cranial arteritis, lupus)

Migraine

Multi-infarct states

Subarachnoid bleeds

Subclavian steal syndrome

Thromboembolic phenomena

Transient ischemic attacks

Mechanical

Concussion

Normal pressure hydrocephalus

Subdural or epidural hematoma

Trauma

Infectious

Abscesses

AIDS

Hepatitis

Meningoencephalitis (including tuberculosis, fungal, herpes)

Multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Subacute sclerosingpanencephalitis

Syphilis

Nutritional

Vitamin B12 deficiency

Folate deficiency

Niacin deficiency

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) deficiency

Thiamine deficiency

Degenerative and neurologic

Aging

Alzheimer’s disease

Heavy metal toxicity

Huntington’s disease

Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease

Multiple sclerosis

Parkinson’s disease

Pick’s disease

Type of Psychiatric Disorder

Examples

Chronic psychosis (severe)

Schizophrenia

Schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type (with prominent episodes of mania)

Schizoaffective disorder, depressed type (with prominent depressive episodes)

Schizophreniform (<6 months’ duration)

Chronic psychosis (less severe or bizarre)

Delusional disorder

Shared psychotic disorder

Episodic psychosis

Depression with psychotic features

Bipolar disorder (manic or depressed)

Brief psychotic disorder

PTSD; borderline personality disorder

Schizophrenia

Assessment

Mechanism of Action

Drug

Potency

D1

D2/EPS Prolactin

D4

5-HT2/Weight Gain

Anti-Cholinergic

α1/Orthostasis

α2

Histamine H1/Sedation

FIRST GENERATION

chlorpromazine (Thorazine)

Low

++

++/++

+/0

++

+/+++

+

+/+++

fluphenazine (Prolixin)

High

+

+/+++

++/0

+

+/+

+++

+/+

perphenazine (Trilafon)

Low

0

++/++

+/0

+

+/+

++

0/++

prochlorperazine (Compazine)

Low

++/+++

+

+

++

trifluoperazine (Stelazine)

High

+++

+

+

+

mesoridazine (Serentil)

0

++/+

+/0

+++

0/++

0

0/+++

thioridazine (Mellaril)

Low

+

++/+

+

+++/0

+++

+/+++

0

0/+++

thiothixene (Navane)

High

+++

+/+++

+++

+++/0

+

+/++

++

+/+

haloperidol (Haldol)

High

++

+/+++

+

+++/0

+

+/+

+++

+++/+

molindone (Moban)

0

+++/++

0

++++/0

+

+++/+

++

+++/++

loxapine (Loxitane)

High

0

+++/++

+

+/0

+

++/+

+++

+/+

SECOND GENERATION

clozapine (Clozaril)

High

+

+/+

+++

++/++++

+++/++

+/++

++

+/+++

risperidone (Risperdal)

High

++/++

++/0

0

+

++

+

iloperidone (Fanapt)

High

+

++/++

+

++/+

0

+/+

+

+

paliperidone (Invega)

High

++/++

++/+

0

+/+

+

+

olanzapine (Zyprexa)

High

+

++/+

++

+/+++

+++/++

+/++

++

+/++

quetiapine (Seroquel)

High

+++

+++/+

+++

+++/+

0/++

++/++

+++

+/++

ziprasidone (Geodon)

High

+++

+/++

+++

+

+++

+

0

++

aripiprazole (Abilify)

High

0

Partial +++/0

D3 +++

Partial 1 and 2A +++; 2c and 7 ++

+/+

+/+

+/+

asenaprine (Saphris)

High

+++

+++/+

+++

+++/+

0

+/+

++

++

lurasidone (Latuda)

High

+++/+

++/0

0

+/+

+

0 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Antipsychotics

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue