Chapter 45 A seizure is an alteration in behavior, function, and/or consciousness that results from an abnormal electrical discharge of neurons in the brain. Epilepsy, or the term seizure disorder, is used to describe chronic unprovoked recurrent seizures. Seizures are classified according to clinical presentation and EEG characteristics. The International Classification of Seizures by the Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy is summarized in Table 45-2. The treatment chosen for seizure disorder depends on the type of seizure; thus, the correct diagnosis of seizure disorder is imperative. Drugs appear in the table in the order in which they usually are initiated for each type of seizure. TABLE 45-2 Seizure Classification and Recommended Medication Therapy ∗Listed in order currently recommended for use, although these recommendations frequently change. • French JA, et al: Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs, I: Treatment of new onset epilepsy: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee and Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society, Neurology 62:1252-1260, 2004. • Practice parameter: treatment of the child with a first unprovoked seizure. Report of the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society, 2012. • Little good-quality evidence has been gathered from clinical trials to support the use of newer monotherapy or adjunctive therapy AEDs over older drugs or to support the use of one newer AED in preference to another. In general, data related to clinical effectiveness, safety, and tolerability have failed to demonstrate consistent and statistically significant differences between drugs. • Newer AEDs, when used as monotherapy, may be cost-effective for the treatment of patients who have experienced adverse events with older AEDs, who have failed to respond to the older drugs, or in whom such drugs are contraindicated. • Partial epilepsy: Beneficial—carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, valproate. Unknown effectiveness—other drugs • Generalized epilepsy: Beneficial—carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, valproate; unknown effectiveness—other drugs • Drug-resistant partial epilepsy: Beneficial—addition of gabapentin, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, tiagabine, topiramate, vigabatrin, or zonisamide • Lamotrigine may be a clinical and cost-effective alternative to existing standard drug treatment—carbamazepine—for patients given a diagnosis of partial seizures. • For patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy or difficult to classify epilepsy, valproate remains the drug that is clinically most effective, although topiramate may be a cost-effective alternative for some patients. • Gabapentin, lamotrigine, topiramate, and oxcarbazepine have efficacy as monotherapy in newly diagnosed adolescents and adults with either partial or mixed seizure disorders. • Lamotrigine is effective for newly diagnosed absence seizures in children. • Evidence is lacking for the effectiveness of the new antiseizure medications in newly diagnosed patients with other generalized epilepsy. • Choose an agent appropriate to the type of seizure. • Choose the least toxic option. Most older antiepileptics are cytochrome P450 inducers and, as such, are involved in many drug–drug interactions. • Initiate monotherapy; start slowly and continue until steady state is reached (five times the half-life). • Titrate the dose upward until control is achieved or adverse reactions occur. • Choose an alternative monotherapy drug if adverse reactions to the first drug occur. • Do not discontinue abruptly because of the possibility of increasing seizure frequency; therapy should be withdrawn gradually to minimize the potential of increased seizure frequency unless safety concerns require a more rapid withdrawal. • All current AEDs pose an increased risk of suicidality (defined as suicidal ideation and behavior), and prescriptions should be accompanied by a patient medication guide describing this risk. • Patients with status epilepticus who are given midazolam through an autoinjector rather than IV lorazepam are more likely to be seizure free by the time they arrive at the hospital and are also less likely to require hospitalization. The medication to use depends on the type of seizure (see Table 45-1). A neurologist generally makes this decision. The medication is started at a low dose and gradually is increased until seizures are controlled or the patient exhibits adverse effects. If the patient continues to experience seizures despite the highest-tolerated dose, a second drug is added gradually. Then the first drug is withdrawn gradually. The use of complementary or alternative medicine may interact with other antiepileptic drugs and must be used cautiously and with the knowledge of the health care provider. See Table 45-3 for a list of some of these potential interactions. TABLE 45-3

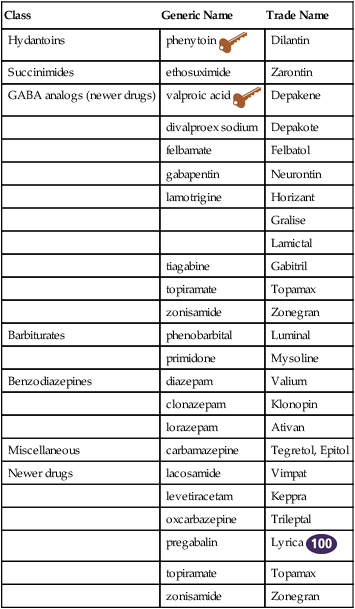

Antiepileptics

Class

Generic Name

Trade Name

Hydantoins

phenytoin ![]()

Dilantin

Succinimides

ethosuximide

Zarontin

GABA analogs (newer drugs)

valproic acid ![]()

Depakene

divalproex sodium

Depakote

felbamate

Felbatol

gabapentin

Neurontin

lamotrigine

Horizant

Gralise

Lamictal

tiagabine

Gabitril

topiramate

Topamax

zonisamide

Zonegran

Barbiturates

phenobarbital

Luminal

primidone

Mysoline

Benzodiazepines

diazepam

Valium

clonazepam

Klonopin

lorazepam

Ativan

Miscellaneous

carbamazepine

Tegretol, Epitol

Newer drugs

lacosamide

Vimpat

levetiracetam

Keppra

oxcarbazepine

Trileptal

pregabalin

Lyrica ![]()

topiramate

Topamax

zonisamide

Zonegran

Therapeutic Overview

Pathophysiology and the Disease Process

Seizure Type

Description

Drug∗

Simple partial

Focal motor or sensory symptoms; reflects area of brain affected; no change in consciousness

phenytoin

carbamazepine

valproic acid

phenobarbital

topiramate

gabapentin

oxcarbazepine

Adjunct—lamotrigine

Adjunct—pregabalin

Adjunct—tiagabine

Adjunct—zonisamide

Complex partial

Characterized by an aura, followed by impaired consciousness with automatisms, usually originating from temporal lobe

carbamazepine

phenytoin

phenobarbital

valproic acid

gabapentin

Secondarily generalized

Simple or complex partial seizures that progress to generalized tonic-clonic seizures

phenytoin

carbamazepine

phenobarbital

valproic acid

Generalized tonic-clonic

Formerly “grand mal”; sudden loss of consciousness with tonic-clonic motor activity, postictal state of confusion, drowsiness, and headache

phenytoin

carbamazepine

phenobarbital

valproic acid

topiramate

Absence

Formerly “petit mal”; brief (<30 seconds) episodes of unresponsiveness characterized by staring, blinking, or facial twitching

ethosuximide

valproic acid

clonazepam

Myoclonic

Series of brief jerky contractions of specific muscle groups

oxcarbazepine

zonisamide

clonazepam

Refractory

Unable to control with other medications

felbamate

levetiracetam

Treatment Principles

Standardized Guidelines

Evidence-Based Recommendations

Cardinal Points of Treatment

Pharmacologic Treatment

![]() Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Herbal Interactions with Common Antiepileptics

Product

Comments

Bitter melon

Potential interactions with insulin, oral hypoglycemics

Chamomile (German or Roman)

May increase effect of antiepileptics such as phenytoin, valproic acid, and barbiturates

Ginkgo

Potential interaction with anticoagulants, aspirin, NSAIDs, antiplatelet drugs; may interact with MAO inhibitors and other antidepressants, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, antihypertensives, insulin, trazodone. High doses decrease effectiveness of antiepileptic medications.

Gymnema

Potential interactions with insulin, oral hypoglycemics

Horsetail

Diuretic effect may enhance action of phenytoin

Kava kava

May increase the effects of medications used to treat seizures

Milk thistle

May interfere with phenytoin

Passionflower

May increase sedative effects of phenytoin, barbiturates

Siberian ginseng

Increases sedative effects of barbiturates

Skullcap (American and Chinese)

Increases sedative effect of barbiturates, benzodiazepines, drugs used to treat insomnia, alcohol, phenytoin, valproic acid

St. John’s wort

May increase the sedation effect of phenytoin and valproic acid, barbiturates

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree