Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Fluoxetine Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor Venlafaxine Tricyclic Antidepressant Imipramine Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor Phenelzine Atypical Antidepressant Bupropion

Drugs Used for Depression

Drugs are the primary therapy for major depression. However, benefits are limited mainly to patients with severe depression. In patients with mild to moderate depression, antidepressants have little or no beneficial effect.

Available antidepressants are listed in Table 25.1. As indicated, these drugs fall into five major classes: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and atypical antidepressants. All of these classes are equally effective, as are the individual drugs within each class. Hence differences among these drugs relate mainly to side effects and drug interactions.

TABLE 25.1

Antidepressant Classes and Adult Dosages

| Generic Name | Trade Name | Availability | Initial Dose*,† (mg/day) | Maintenance Dose* (mg/day) |

| SELECTIVE SEROTONIN REUPTAKE INHIBITORS (SSRIs) | ||||

| Citalopram | Celexa | 10 mg/5 mL oral solution 10-, 20-, 40-mg tablets | 20 | 20–40 |

| Escitalopram | Lexapro, Cipralex  | 5 mg/5 mL oral solution 5-, 10-, 20-mg tablets | 10 | 10–20 |

| Fluoxetine | Prozac, Sarafem, Selfemra | 20 mg/5 mL oral solution 10-, 20-, 60-mg tablets 90-mg delayed release tablets 10-, 20-, 40-mg capsules | 20 | 20–80 |

| Fluvoxamine‡ | Luvox | 25-, 50-, 100-mg tablets 100-, 150-mg controlled-release capsules | 50 | 100–300 |

| Paroxetine | Paxil, Pexeva | 10 mg/5 mL oral solution 10-, 20-, 30-, 40-mg tablets 12.5-, 25-, 37.5-mg controlled-release tablets | 12.5–20 | 20–50 |

| Sertraline | Zoloft | 20 mg/mL oral solution 25-, 50-, 100-mg tablets | 50 | 50–200 |

| SEROTONIN-NOREPINEPHRINE REUPTAKE INHIBITORS (SNRIs) | ||||

| Desvenlafaxine | Pristiq | 50-, 100-mg extended-release tablets | 50 | 50–100 |

| Duloxetine | Cymbalta | 20-, 30-, 60-mg delayed-release tablets | 40–60 | 60–120 |

| Levomilnacipran | Fetzima | 20-, 40-, 80-, 120-mg capsules | 20 mg | 40–120 |

| Venlafaxine | Effexor XR | 25-, 37.5-, 50-, 75-, 100-mg tablets 37.5-, 75-, 150-, 225-mg extended-release tablets 37.5-, 75-, 150-mg extended-release capsules | 37.5–75 | 75–375 |

| TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS (TCAs) | ||||

| Amitriptyline | generic only | 10-, 25-, 50-, 75-, 100-, 125-, 150-mg tablets | 25–50 | 100–300 |

| Clomipramine‡ | Anafranil | 25-, 50-, 75-mg tablets | 25 | 100–250 |

| Desipramine | Norpramin | 10-, 25-, 50-, 75-, 100-, 150-mg tablets | 25–50 | 100–300 |

| Doxepin | Sinequan§ | 10 mg/mL oral solution 10-, 25-, 50-, 75-, 100-, 150-mg tablets | 50 | 75–300 |

| Imipramine | Tofranil | 10-, 25-, 50-mg tablets 75-, 100-, 125-, 150-mg capsules | 25–50 | 100–200 |

| Maprotiline | generic only | 25-, 50-, 75-mg tablets | 75 | 100–225 |

| Nortriptyline | Aventyl, Pamelor | 10 mg/5 mL oral solution 10-, 25-, 50-, 75-mg tablets | 75–100 | 50–150 |

| Protriptyline | Vivactil | 5-, 10-mg tablets | 15–40 | 20–60 |

| Trimipramine | Surmontil | 10-mg tablets | 75–100 | 75–200 |

| MONOAMINE OXIDASE INHIBITORS (MAOIs) | ||||

| Isocarboxazid | Marplan | 10-mg tablets | 10–20 | 30–60 |

| Phenelzine | Nardil | 15-mg tablets | 45 | 60–90 |

| Selegiline (transdermal) | Emsam | 6-, 9-, 12-mg/24 hr transdermal patches | 6 | 6–12 |

| Tranylcypromine | Parnate | 10-mg tablets | 10–30 | 30–60 |

| ATYPICAL ANTIDEPRESSANTS | ||||

| Amoxapine | generic only | 25-, 50-, 100-, 150-mg tablets | 100 | 200–400 |

| Bupropion | Wellbutrin, others | 75-, 100-mg tablets 100-, 150-, 200-, 300-mg sustained-release tablets | 200 | 300–450 |

| Mirtazapine | Remeron | 7.5-, 15-, 30-, 45-mg tablets 15-, 30-, 45-mg orally disintegrating tablets | 15 | 15–45 |

| Nefazodone | generic only | 50-, 100-, 150-, 200-, 250-mg tablets | 200 | 300–600 |

| Trazodone | generic only | 50-, 100-, 150-, 300- mg tablets | 150 | 150–600 |

| Trazodone ER | Oleptro | 150-, 300-mg extended-release tablets | 150 | 150–375 |

| Vilazodone | Viibryd | 10-, 20-, 40-mg tablets | 10 | 40 |

Basic Considerations

In this section we consider basic issues that apply to all antidepressant drugs. The information on suicide risk is especially important.

Time Course of Response

With all antidepressants, symptoms resolve slowly. Initial responses develop in 1 to 3 weeks. Maximal responses may not be seen until 12 weeks. Because therapeutic effects are delayed, antidepressants cannot be used PRN. Furthermore, a therapeutic trial should not be considered a failure until a drug has been taken for at least 1 month without success.

Drug Selection

Because all antidepressants have nearly equal efficacy, selection among them is based largely on tolerability and safety. Additional considerations are drug interactions, patient preference, and cost. The usual drugs of first choice are the SSRIs, SNRIs, bupropion, and mirtazapine. Older antidepressants—TCAs and MAOIs—have more adverse effects and are less well tolerated than the first-line agents and hence are generally reserved for patients who have not responded to the first-line drugs.

In some cases, the side effects of a drug, when matched to the right patient, can actually be beneficial. Here are some examples:

• For a patient with fatigue, choose a drug that causes central nervous system (CNS) stimulation (e.g., fluoxetine, bupropion).

• For a patient with insomnia, choose a drug that causes substantial sedation (e.g., mirtazapine).

• For a patient with sexual dysfunction, choose bupropion, a drug that enhances libido.

• For a patient with chronic pain, choose duloxetine or a TCA, drugs that can relieve chronic pain.

Managing Treatment

After a drug has been selected for initial treatment, it should be used for 4 to 8 weeks to assess efficacy. As a rule, dosage should be low initially (to reduce side effects) and then gradually increased (see Table 25.1). If the initial drug is not effective, we have four major options:

• Switch to another drug in the same class.

• Switch to another drug in a different class.

• Add a second drug, such as lithium or an atypical antidepressant.

After symptoms are in remission, treatment should continue for at least 4 to 9 months to prevent relapse. To this end, patients should be encouraged to take their drugs even if they are symptom free and hence feel that continued dosing is unnecessary. When antidepressant therapy is discontinued, dosage should be gradually tapered over several weeks because abrupt withdrawal can trigger withdrawal symptoms.

To reduce the risk for suicide, patients taking antidepressant drugs should be observed closely for suicidality, worsening mood, and unusual changes in behavior. Close observation is especially important during the first few months of therapy and whenever antidepressant dosage is changed (either increased or decreased). Ideally, the patient or caregiver should meet with the prescriber at least weekly during the first 4 weeks of treatment, then biweekly for the next 4 weeks, then once 1 month later, and periodically thereafter. Phone contact may be appropriate between visits. In addition, family members or caregivers should monitor the patient daily, being alert for symptoms of decline (e.g., anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility, impulsivity, hypomania, and, of course, emergence of suicidality). If these symptoms are severe or develop abruptly, the patient should see his or her prescriber immediately.

Because antidepressant drugs can be used to commit suicide, prescriptions should be written for the smallest number of doses consistent with good patient management. What should be done if suicidal thoughts emerge during drug therapy, or if depression is persistently worse while taking drugs? One option is to switch to another antidepressant. However, as noted, the risk for suicidality appears equal with all antidepressants. Another option is to stop antidepressants entirely. However, this option is probably unwise because the long-term risk for suicide from untreated depression is much greater than the long-term risk associated with antidepressant drugs. If the risk for suicide appears high, temporary hospitalization may be the best protection.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

The SSRIs were introduced in 1987 and have since become our most commonly prescribed antidepressants, accounting for more than $3 billion in annual sales. These drugs are indicated for major depression as well as several other psychological disorders (Table 25.2). Characteristic side effects are nausea, agitation and insomnia, and sexual dysfunction (especially anorgasmia). Like all other antidepressants, SSRIs may increase the risk for suicide. Compared with the TCAs and MAOIs, SSRIs are equally effective, better tolerated, and much safer. Death by overdose is extremely rare.

TABLE 25.2

Therapeutic Uses of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

| Therapeutic Use* | |||||||||

| Drug | Major Depression | OCD | Panic Disorder | Social Phobia | GAD | PTSD | PMDD | Bulimia Nervosa | Chronic Pain Disorders† |

| Citalopram [Celexa] | A | U | U | U | U | U | U | ||

| Escitalopram [Lexapro] | A | A | U | A | U | ||||

| Fluoxetine [Prozac] | A | A | A | U | U | U | A | A | |

| Fluvoxamine [Luvox] | U | A | U | A | U | U | U | U | |

| Paroxetine [Paxil] | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | ||

| Sertraline [Zoloft] | A | A | A | A | U | A | A | ||

| Desvenlafaxine [Pristiq] | A | U | U | U | U | ||||

| Duloxetine [Cymbalta] | A | A | A | ||||||

| Levomilnacipran [Fetzima] | A | U | U | ||||||

| Venlafaxine [Effexor] | A | A | A | U | |||||

Fluoxetine

Fluoxetine [Prozac, Prozac Weekly], the first SSRI available, will serve as our prototype for the group. At one time, this drug was the most widely prescribed antidepressant in the world.

Mechanism of Action

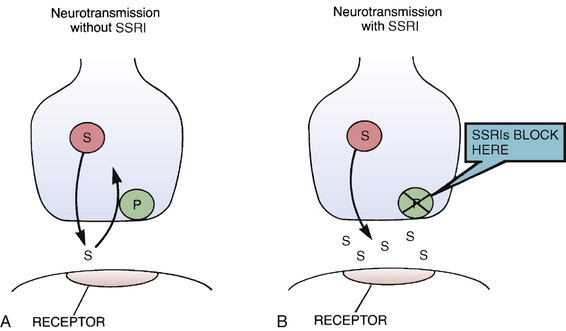

The mechanism of action of fluoxetine and the other SSRIs is depicted in Fig. 25.1. As shown, SSRIs selectively block neuronal reuptake of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]), a monoamine neurotransmitter. As a result of reuptake blockade, the concentration of 5-HT in the synapse increases, causing increased activation of postsynaptic 5-HT receptors. This mechanism is consistent with the theory that depression stems from a deficiency in monoamine-mediated transmission—and hence should be relieved by drugs that can intensify monoamine effects.

It is important to appreciate that blockade of 5-HT reuptake, by itself, cannot fully account for therapeutic effects. Clinical responses to SSRIs (relief of depressive symptoms) and the biochemical effect of the SSRIs (blockade of 5-HT reuptake) do not occur in the same time frame. That is, whereas SSRIs block 5-HT reuptake within hours of dosing, relief of depression takes several weeks to fully develop. This delay suggests that therapeutic effects are the result of adaptive cellular changes that take place in response to prolonged reuptake blockade. Fluoxetine and the other SSRIs do not block reuptake of dopamine or norepinephrine (NE). In contrast to the TCAs (see later), fluoxetine does not block cholinergic, histaminergic, or alpha1-adrenergic receptors. Furthermore, fluoxetine produces CNS excitation rather than sedation.

Therapeutic Uses

Fluoxetine is used primarily for major depression. In addition, the drug is approved for bipolar disorder (see Chapter 26), obsessive-compulsive disorder (see Chapter 28), panic disorder (see Chapter 28), bulimia nervosa, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (see Chapter 48).

Pharmacokinetics

Fluoxetine is well absorbed after oral administration, even in the presence of food. The drug is widely distributed and highly bound to plasma proteins. Fluoxetine undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism, primarily by CYP2D6 (the 2D6 isoenzyme of cytochrome P450). The major metabolite—norfluoxetine—is active, and later undergoes metabolic inactivation, followed by excretion in the urine. The half-life of fluoxetine is 2 days, and the half-life of norfluoxetine is 7 days. Because the effective half-life is prolonged, about 4 weeks are required to produce steady-state plasma drug levels—and about 4 weeks are required for washout after dosing stops.

Adverse Effects

Fluoxetine is safer and better tolerated than TCAs and MAOIs. Death from overdose with fluoxetine alone has not been reported. In contrast to TCAs, fluoxetine does not block receptors for histamine, NE, or acetylcholine and hence does not cause sedation, orthostatic hypotension, anticholinergic effects, or cardiotoxicity. The most common side effects are sexual dysfunction, nausea, headache, and manifestations of CNS stimulation, including nervousness, insomnia, and anxiety. Weight gain can also occur.

Sexual Dysfunction.

Fluoxetine causes sexual problems (impotence, delayed or absent orgasm, delayed or absent ejaculation, decreased sexual interest) in nearly 70% of men and women. The underlying mechanism is unknown.

Sexual dysfunction can be managed in several ways. In some cases, reducing the dosage or taking “drug holidays” (e.g., discontinuing medication on Fridays and Saturdays) can help. Another solution is to add a drug that can overcome the problem. Among these are yohimbine, buspirone [BuSpar], and three atypical antidepressants: bupropion [Wellbutrin, others], nefazodone, and mirtazapine [Remeron]. Drugs such as sildenafil [Viagra] can also help: In men, these drugs improve erectile dysfunction as well as arousal, ejaculation, orgasm, and overall satisfaction; in women, they can improve delayed orgasm. If all of these measures fail, the patient can try a different antidepressant. Agents that cause the least sexual dysfunction are the same three atypical antidepressants just mentioned.

Sexual problems often go unreported, either because patients are uncomfortable discussing them or because patients don’t realize their medicine is the cause. Accordingly, patients should be informed about the high probability of sexual dysfunction and told to report any problems so that they can be addressed.

Weight Gain.

Like many other antidepressants, fluoxetine and other SSRIs cause weight gain. When these drugs were first introduced, we thought they caused weight loss. During the first few weeks of therapy patients lose weight, perhaps because of drug-induced nausea and vomiting. However, with long-term treatment, the lost weight is regained. Furthermore, about one third of patients continue gaining weight. Although the reason is unknown, a good possibility is decreased sensitivity of 5-HT receptors that regulate appetite.

Serotonin Syndrome.

By increasing serotonergic transmission in the brainstem and spinal cord, fluoxetine and other SSRIs can cause serotonin syndrome. This syndrome usually begins 2 to 72 hours after treatment onset. Signs and symptoms include altered mental status (agitation, confusion, disorientation, anxiety, hallucinations, poor concentration) as well as incoordination, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, excessive sweating, tremor, and fever. Deaths have occurred. The syndrome resolves spontaneously after discontinuing the drug. The risk for serotonin syndrome is increased by concurrent use of MAOIs and other drugs (see later section “Drug Interactions”).

Neonatal Effects From Use in Pregnancy.

Use of fluoxetine and other SSRIs late in pregnancy poses a small risk for two adverse effects in the newborn: (1) neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and (2) persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). NAS is characterized by irritability, abnormal crying, tremor, respiratory distress, and possibly seizures. The syndrome can be managed with supportive care and generally abates within a few days. PPHN, which compromises tissue oxygenation, carries a significant risk for death, and, among survivors, a risk for cognitive delay, hearing loss, and neurologic abnormalities. Treatment measures include providing ventilatory support, giving oxygen and nitric oxide (to dilate pulmonary blood vessels), and giving intravenous (IV) sodium bicarbonate (to maintain alkalosis) and dopamine or dobutamine (to increase cardiac output and thereby maintain pulmonary perfusion). Infants exposed to SSRIs late in gestation should be monitored closely for NAS and PPHN.

Teratogenesis.

The risk for birth defects when taking fluoxetine and other SSRIs appears to be very low. Two SSRIs—paroxetine and fluoxetine—may cause septal heart defects. But even with these agents, the absolute risk is very low.

Extrapyramidal Side Effects.

SSRIs cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPSs) in about 0.1% of patients. This is much less frequent than among patients taking antipsychotic medications (see Chapter 24). Among patients taking SSRIs, the most common EPS is akathisia, characterized by restlessness and agitation. However, parkinsonism, dystonic reactions, and tardive dyskinesia can also occur. EPSs typically develop during the first month of treatment. The risk is increased by concurrent use of an antipsychotic drug. The underlying cause of SSRI-induced EPSs may be alteration of serotonergic transmission within the extrapyramidal system. For a detailed discussion of EPSs, refer to Chapter 24.

Bruxism.

SSRIs may cause bruxism (clenching and grinding of teeth). However, because bruxism usually occurs during sleep, the condition often goes unrecognized. Sequelae of bruxism include headache, jaw pain, and dental problems (e.g., cracked fillings).

SSRIs may cause bruxism by inhibiting release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that suppresses activity in certain muscles, including those of the jaw. By decreasing dopamine availability, SSRIs could release these muscles from inhibition, and excessive activity could result. This same mechanism may be responsible for SSRI-induced EPSs.

Bruxism can be managed by reducing the SSRI dosage. However, this may cause depression to return. Other options include switching to a different class of antidepressant, use of a mouth guard, and treatment with low-dose buspirone.

Bleeding Disorders.

Fluoxetine and other SSRIs can increase the risk for bleeding in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and at other sites by impeding platelet aggregation. Platelets require 5-HT for aggregation, but can’t make it themselves, and hence must take 5-HT up from the blood; by blocking 5-HT uptake, SSRIs suppress aggregation. The SSRIs cause a threefold increase in the risk for GI bleeding. However, the absolute risk is still low (about 1%). Caution is advised in patients with ulcers or a history of GI bleeding, in patients older than 60 years, and in patients taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or anticoagulants.

Hyponatremia.

Fluoxetine can cause hyponatremia (serum sodium <135 mEq/L), probably by increasing secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Most cases involve older-adult patients taking thiazide diuretics. Accordingly, when fluoxetine is used in older-adult patients, sodium should be measured at baseline and periodically thereafter.

Other Adverse Effects.

Fluoxetine may cause dizziness and fatigue; patients who experience intense dizziness and fatigue should be warned against driving and other hazardous activities. Skin rash, which can be severe, has occurred in 4% of patients; in most cases, rashes readily respond to drug therapy (antihistamines, glucocorticoids) or to withdrawal of fluoxetine. Other common reactions include diarrhea and excessive sweating.

Drug Interactions

MAOIs and Other Drugs That Increase the Risk for Serotonin Syndrome.

MAOIs increase 5-HT availability and hence greatly increase the risk for serotonin syndrome. Accordingly, use of MAOIs with SSRIs is contraindicated. Because MAOIs cause irreversible inhibition of monoamine oxidase (MAO; see later), their effects persist long after dosing stops. Therefore MAOIs should be withdrawn at least 14 days before starting an SSRI. Because fluoxetine and its active metabolite have long half-lives, at least 5 weeks should elapse between stopping fluoxetine and starting an MAOI. For other SSRIs, at least 2 weeks should elapse between treatment cessation and starting an MAOI.

Other drugs that increase the risk for serotonin syndrome include the serotonergic drugs listed in Table 25.3, drugs that inhibit CYP2D6 (and thereby raise fluoxetine levels), tramadol (an analgesic), and linezolid (an antibiotic that inhibits MAO).

TABLE 25.3

Drugs That Promote Activation of Serotonin Receptors

| Drug | Mechanism |

| SELECTIVE SEROTONIN REUPTAKE INHIBITORS (SSRIs) | |

Citalopram [Celexa] Escitalopram [Lexapro, Cipralex Fluoxetine [Prozac] Fluvoxamine [Luvox] Paroxetine [Paxil] Sertraline [Zoloft] | Block 5-HT reuptake and thereby increase 5-HT in the synapse |

| SEROTONIN/NOREPINEPHRINE REUPTAKE INHIBITORS (SNRIs) | |

Desvenlafaxine [Pristiq] Duloxetine [Cymbalta] Venlafaxine [Effexor XR] Levomilnacipran [Fetzima] | Same as SSRIs |

| TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS (TCAs) | |

Amitriptyline Clomipramine [Anafranil] Desipramine [Norpramin] Doxepin [Sinequan] Imipramine [Tofranil] Trimipramine [Surmontil] | Same as SSRIs |

| MONOAMINE OXIDASE INHIBITORS (MAOIs) | |

Isocarboxazid [Marplan] Phenelzine [Nardil] Selegiline [Emsam] | Inhibit neuronal breakdown of 5-HT by MAO and thereby increase stores of 5-HT available for release |

| ATYPICAL ANTIDEPRESSANTS | |

| Mirtazapine [Remeron] | Promotes release of 5-HT |

| Nefazodone | Same as SSRIs |

| Trazodone [Oleptro] | Same as SSRIs |

| ANALGESICS | |

| Meperidine [Demerol] | Same as SSRIs and MAOIs |

| Methadone [Dolophine] | Same as SSRIs and MAOIs |

| Tramadol [Ultram] | Same as SSRIs |

| TRIPTAN ANTIMIGRAINE DRUGS | |

Almotriptan [Axert] Eletriptan [Relpax] Frovatriptan [Frova] Rizatriptan [Maxalt] Sumatriptan [Imitrex] Zolmitriptan [Zomig] | Cause direct activation of serotonin receptors |

| OTHERS | |

| St. John’s wort | Same as SSRIs and MAOIs |

| Linezolid [Zyvox] | Same as MAOIs |

Tricyclic Antidepressants and Lithium.

Fluoxetine can elevate plasma levels of TCAs and lithium. Exercise caution if fluoxetine is combined with these agents.

Antiplatelet Drugs and Anticoagulants.

Antiplatelet drugs (e.g., aspirin, NSAIDs) and anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin) increase the risk for GI bleeding. Exercise caution if fluoxetine is combined with these drugs.

The risk for bleeding with warfarin is compounded by a pharmacokinetic interaction. Because fluoxetine is highly bound to plasma proteins, it can displace other highly bound drugs. Displacement of warfarin is of particular concern. Monitor responses to warfarin closely.

Drugs That Are Substrates for or Inhibitors of CYP2D6.

Fluoxetine and most other SSRIs are inactivated by CYP2D6. Accordingly, drugs that inhibit this enzyme can raise SSRI levels, thereby posing a risk for toxicity.

In addition to being a substrate for CYP2D6, fluoxetine itself can inhibit CYP2D6. As a result, fluoxetine can raise levels of other drugs that are CYP2D6 substrates. Among these are TCAs, several antipsychotics, and two antidysrhythmics: propafenone and flecainide. Combined use of fluoxetine with these drugs should be done with caution.

Other Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

In addition to fluoxetine, five other SSRIs are available: citalopram [Celexa], escitalopram [Lexapro, Cipralex  ], fluvoxamine [Luvox], paroxetine [Paxil, Pexeva], and sertraline [Zoloft]. All five are similar to fluoxetine. Antidepressant effects equal those of TCAs. Characteristic side effects are nausea, insomnia, headache, nervousness, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, hyponatremia, GI bleeding, and NAS and PPHN (in infants who were exposed to these drugs late in gestation). Serotonin syndrome is a potential complication with all SSRIs, especially if these agents are combined with MAOIs or other serotonergic drugs. The principal differences among the SSRIs relate to duration of action. Patients who experience intolerable adverse effects with one SSRI may find a different SSRI more acceptable. As with fluoxetine, withdrawal should be done slowly. In contrast to the TCAs, the SSRIs do not cause hypotension or anticholinergic effects and, with the exception of fluvoxamine, do not cause sedation. When taken in overdose, these drugs do not cause cardiotoxicity. Therapeutic uses for individual SSRIs are shown in Table 25.2.

], fluvoxamine [Luvox], paroxetine [Paxil, Pexeva], and sertraline [Zoloft]. All five are similar to fluoxetine. Antidepressant effects equal those of TCAs. Characteristic side effects are nausea, insomnia, headache, nervousness, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, hyponatremia, GI bleeding, and NAS and PPHN (in infants who were exposed to these drugs late in gestation). Serotonin syndrome is a potential complication with all SSRIs, especially if these agents are combined with MAOIs or other serotonergic drugs. The principal differences among the SSRIs relate to duration of action. Patients who experience intolerable adverse effects with one SSRI may find a different SSRI more acceptable. As with fluoxetine, withdrawal should be done slowly. In contrast to the TCAs, the SSRIs do not cause hypotension or anticholinergic effects and, with the exception of fluvoxamine, do not cause sedation. When taken in overdose, these drugs do not cause cardiotoxicity. Therapeutic uses for individual SSRIs are shown in Table 25.2.

Sertraline

Sertraline [Zoloft] is much like fluoxetine: both drugs block reuptake of 5-HT, both relieve symptoms of major depression, both cause CNS stimulation rather than sedation, and both have minimal effects on seizure threshold and the electrocardiogram (ECG). Sertraline is indicated for major depression, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and social anxiety disorder. Sertraline is slowly absorbed after oral administration. Food increases the extent of absorption. In the blood, the drug is highly bound (99%) to plasma proteins. Sertraline undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism followed by elimination in the urine and feces. The plasma half-life is approximately 1 day.

Common side effects include headache, tremor, insomnia, agitation, nervousness, nausea, diarrhea, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction. Treatment may also increase the risk for suicide. Because of the risk for serotonin syndrome, sertraline must not be combined with MAOIs and other serotonergic drugs (see Table 25.3). MAOIs should be withdrawn at least 14 days before starting sertraline, and sertraline should be withdrawn at least 14 days before starting an MAOI. Because of a risk for pimozide-induced dysrhythmias, sertraline (which raises pimozide levels) and pimozide should not be combined. Like fluoxetine and other SSRIs, sertraline poses a risk for hyponatremia, GI bleeding, and NAS and PPHN when used late in pregnancy.

Fluvoxamine

Like other SSRIs, fluvoxamine [Luvox] produces powerful and selective inhibition of 5-HT reuptake. The drug is approved for obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder, bulimia, and panic disorder. Fluvoxamine is rapidly absorbed from the GI tract, in both the presence and absence of food. The drug undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism followed by excretion in the urine. The half-life is about 15 hours.

Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, headache, constipation, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction. In contrast to other SSRIs, fluvoxamine has moderate sedative effects, although it nonetheless can cause insomnia. Some patients have developed abnormal liver function tests. Accordingly, liver function should be assessed before treatment and weekly during the first month of therapy. Like other SSRIs, fluvoxamine interacts adversely with MAOIs and other serotonergic drugs, and hence these combinations must be avoided. As with other SSRIs, fluvoxamine poses a risk for hyponatremia, GI bleeding, and NAS and PPHN in infants exposed to the drug in utero.

Paroxetine

Like other SSRIs, paroxetine [Paxil, Paxil CR, Pexeva] produces powerful and selective inhibition of 5-HT reuptake. The drug is indicated for major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes). Paroxetine is well absorbed after oral administration, even in the presence of food. The drug is widely distributed and highly bound (95%) to plasma proteins. Concentrations in breast milk equal those in plasma. The drug undergoes hepatic metabolism followed by renal excretion. The half-life is about 20 hours.

Side effects are dose dependent and generally mild. Early reactions include nausea, somnolence, sweating, tremor, and fatigue. These tend to diminish over time. After 5 to 6 weeks, the major complaints are headache, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction. Like fluoxetine, paroxetine causes signs of CNS stimulation (increased awakenings, reduced time in rapid-eye-movement sleep, insomnia). In contrast to TCAs, paroxetine has no effect on heart rate, blood pressure, or the ECG—but does have some antimuscarinic effects. Like other SSRIs, paroxetine interacts adversely with MAOIs and other serotonergic drugs, and hence these combinations must be avoided. Also, like other SSRIs, paroxetine can increase the risk for GI bleeding and can cause hyponatremia (especially in older-adult patients taking thiazide diuretics). As with other SSRIs, use late in pregnancy can result in NAS and PPHN. In addition, paroxetine, but not other SSRIs (except possibly fluoxetine), poses a small risk for cardiovascular birth defects, primarily ventricular septal defects. Because of this risk, the drug is classified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as Pregnancy Risk Category D. Like all other antidepressants, paroxetine may increase the risk for suicide, especially in children and young adults.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Black Box Warning: Suicide Risk With Antidepressant Drugs

Black Box Warning: Suicide Risk With Antidepressant Drugs ]

]