Chapter 26 Providers must ask specifically about antacids and other OTC remedies when taking a medication history. Many patients will have tried OTC remedies before going to their primary care provider. Most will have tried antacids, OTC histamine blockers, or proton pump inhibitors (see Chapter 27). Many patients do not consider antacids to be a medication and will not mention taking them when asked about medication use. • American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement: Evaluation of Dyspepsia (http://www.guidelines.gov/) on the Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/50016-5085(08)01606-5/full text 2008. • Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF et al: American Gastroenterological association medical position statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease, Gastroenterology 135(4):1383-1391, 2008. • DeVault KR, Castell DO: Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology, Am J Gastroenterol 94:1434, 1999. • Patients should begin by making lifestyle changes in diet and by managing stress. • For patients with esophageal GERD syndromes, treatment with antisecretory drugs is recommended for healing esophagitis, symptomatic relief, and maintenance of esophageal healing. In this situation proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are more effective than histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs), which, in turn, are more effective than placebo. • Once PPIs have proven clinically effective for the treatment of patients with esophagitis, therapy should be continued long-term and titrated down to the lowest effective dose on the basis of symptom control. • When treatment with antireflux surgery or PPIs is thought to be similarly effective in a patient with an esophageal GERD syndrome, PPI therapy is considered safer and is therefore preferred as initial treatment. • Antireflux surgery should be recommended when a patient with an esophageal GERD syndrome cannot tolerate acid suppressive therapy, even if pharmacotherapy is effective. • In patients with suspected reflux chest pain syndrome, an empiric trial of twice-daily PPI therapy is recommended after careful evaluation for a cardiac cause. • Patients should begin by making lifestyle changes in diet and by managing stress. • Diagnostic Guideline 1: Empirical Therapy—If a patient’s history is typical for uncomplicated GERD, an initial trial of empirical therapy is appropriate (with lifestyle modification, particularly weight loss and diet control in obese patients). Lack of response does not rule out GERD. Additional testing should be considered if GERD symptoms are refractory to empirical therapy. • Treatment Guideline II: Patient-Directed Therapy—Antacids, H2-receptor antagonists, and omeprazole are available OTC in the United States. Patients should not self-medicate for longer than 14 days without further evaluation. • Treatment Guideline III: Acid Suppression—The mainstay of treatment for GERD is acid suppression. • PPIs—PPIs are first-line treatment because they are the most effective option. Few data favor one agent over another. Long-term therapy is beneficial in chronic and complicated GERD. Higher than approved dosages may be indicated in certain situations. To achieve optimal benefit, PPIs should be taken 30 to 60 minutes prior to the timing of other medications, breakfast, or the evening meal. • H2 receptor agonists—H2 receptor agonists may be used as premedication before meals. Efficacy may outlast that of antacids. Once-a-day dosing is not appropriate as long-term therapy for GERD. • Promotility agents (cisapride and metoclopramide)—These have poor side effect profiles but may be used as adjunctive acid suppression therapy for GERD. Promotility agents may eliminate the root cause of GERD and may make acid suppression unnecessary. Promotility agents are not effective as monotherapy for GERD. • The goals of treatment include symptomatic relief and prevention of complications. GERD is a lifelong disease that requires lifestyle modifications and medications as indicated.

Antacids and the Management of GERD

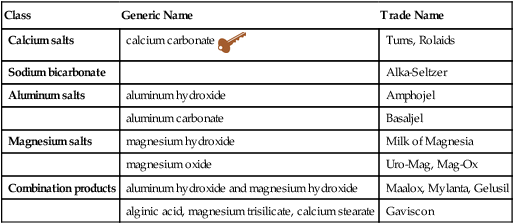

Class

Generic Name

Trade Name

Calcium salts

calcium carbonate ![]()

Tums, Rolaids

Sodium bicarbonate

Alka-Seltzer

Aluminum salts

aluminum hydroxide

Amphojel

aluminum carbonate

Basaljel

Magnesium salts

magnesium hydroxide

Milk of Magnesia

magnesium oxide

Uro-Mag, Mag-Ox

Combination products

aluminum hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide

Maalox, Mylanta, Gelusil

alginic acid, magnesium trisilicate, calcium stearate

Gaviscon

![]() Key drug, as it is the most commonly used except for the combination products.

Key drug, as it is the most commonly used except for the combination products.

Therapeutic Overview of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Anatomy and Physiology

Disease Process

Treatment Principles

Standardized Guidelines

Cardinal Points of Treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Antacids and the Management of GERD

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue