Anatomy of the Digestive System

ORGANIZATION OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

Organs of Digestion

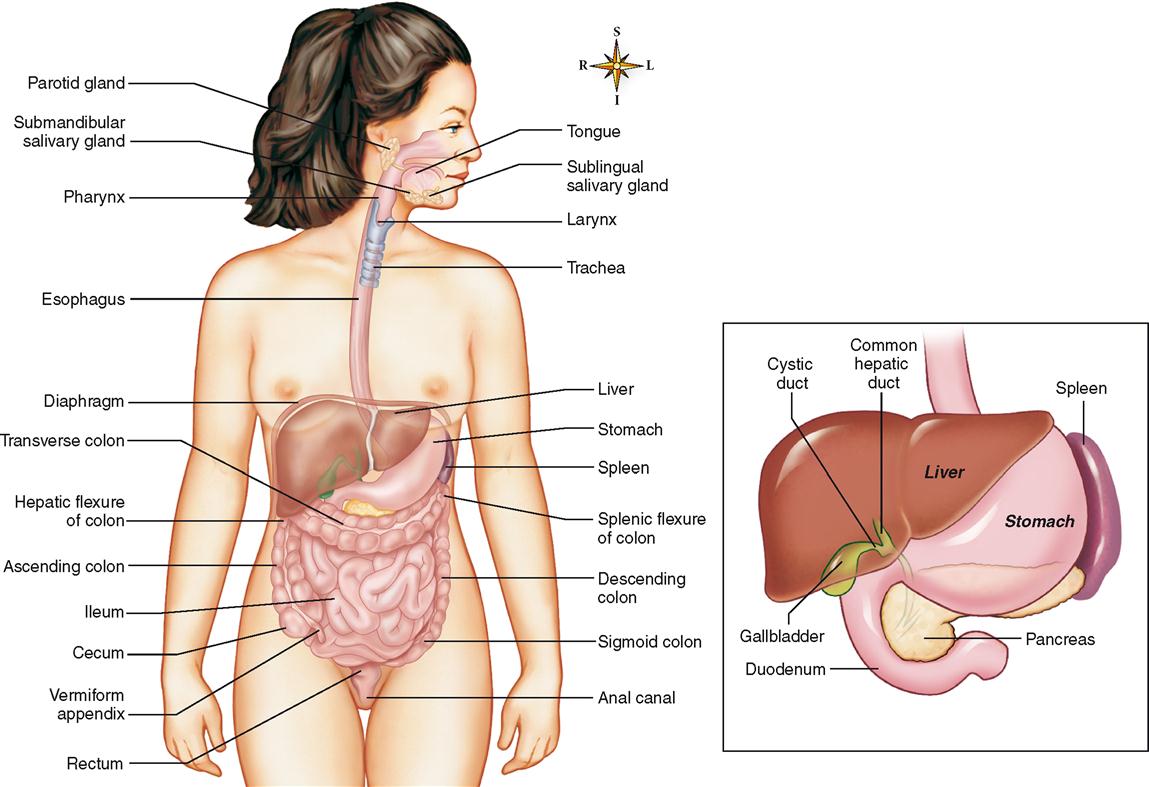

The main organs of the digestive system (Figure 28-1) form a tube that goes all the way through the ventral cavities of the body. It is open at both ends. This tube is usually referred to as the alimentary canal (tract). The term gastrointestinal (GI) tract refers only to the stomach and intestines but is sometimes used in reference to the entire alimentary canal.

It is important to realize that ingested food material passing through the lumen of the GI tract is actually outside the internal environment of the body, even though the tube itself is inside the ventral body cavity.

Box 28-1 lists the main organs of the digestive system, that is, the segments of the alimentary canal, and the accessory organs located in the main digestive organs or opening into them. Organs such as the larynx, trachea, diaphragm, and spleen are labeled in Figure 28-1, but they are not digestive organs. They are shown to assist in orienting the digestive organs to other important body structures.

Wall of the GI Tract

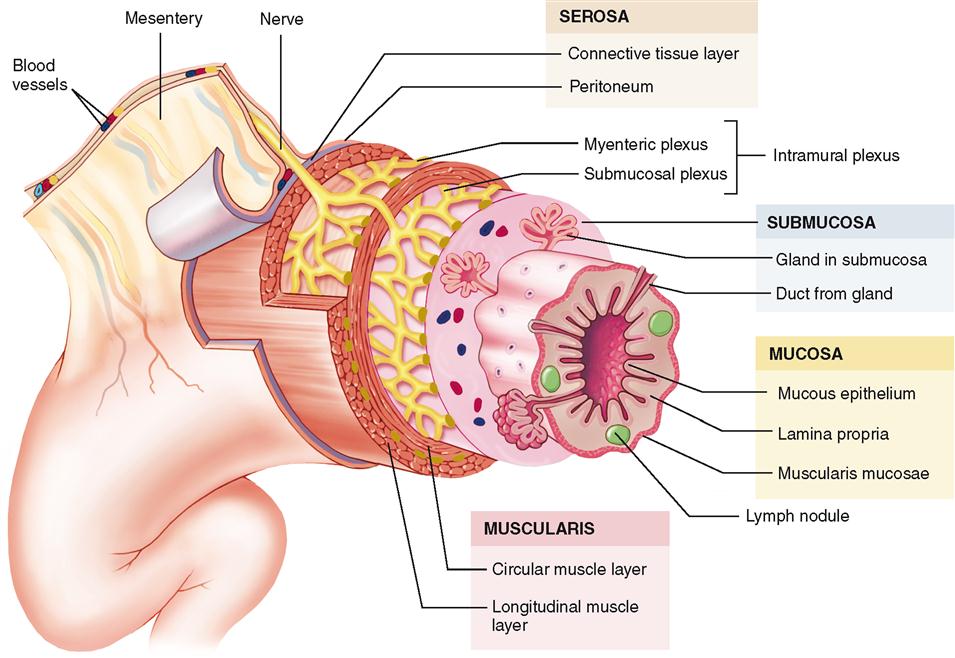

The GI tract is essentially a tube with walls fashioned of four layers of tissues: a mucous lining, a submucous coat of connective tissue in which are embedded the main blood vessels of the tract, a muscular layer, and a fibroserous layer (Figure 28-2). Blood vessels and nerves travel through the mesentery to reach the digestive tube throughout most of its length.

MUCOSA

The innermost layer of the GI wall—the layer facing the lumen, or open space, of the tube—is called the mucosa or mucous layer. Note in Figure 28-2 that the mucosa is made up of three layers—an inner mucous epithelium, a layer of loose fibrous connective tissue called the lamina propria, and a thin layer of smooth muscle called the muscularis mucosae.

SUBMUCOSA

The submucosa layer of the digestive tube is composed of connective tissue that is thicker than the mucosal layer. It contains numerous small glands, blood vessels, and parasympathetic nerves that form the submucosal plexus (Meissner plexus).

MUSCULARIS

The muscularis—or muscular layer—is a thick layer of muscle tissue that wraps around the submucosa. This portion of the wall is characterized by an inner layer of circular and an outer layer of longitudinal smooth muscle. Like the submucosa, the muscularis contains nerves organized into a plexus called the myenteric plexus (Auerbach plexus). This plexus lies between the two muscle layers. Note in Figure 28-2 that the term intramural plexus is used to describe both plexuses. Together they play an important role in the regulation of digestive tract movement and secretion.

SEROSA

The serosa—or serous layer—is the outermost layer of the GI wall. It is made up of serous membrane (see Figures 6-39 and 6-40 on pp. 639 and 640). The serosa is actually the visceral layer of the peritoneum—the serous membrane that lines the abdominopelvic cavity and covers its organs. The lining attached to and covering the walls of the abdominopelvic cavity is called the parietal layer of the peritoneum. The fold of serous membrane shown in Figure 28-2 that connects the parietal and visceral portions is called a mesentery.

MODIFICATIONS OF LAYERS

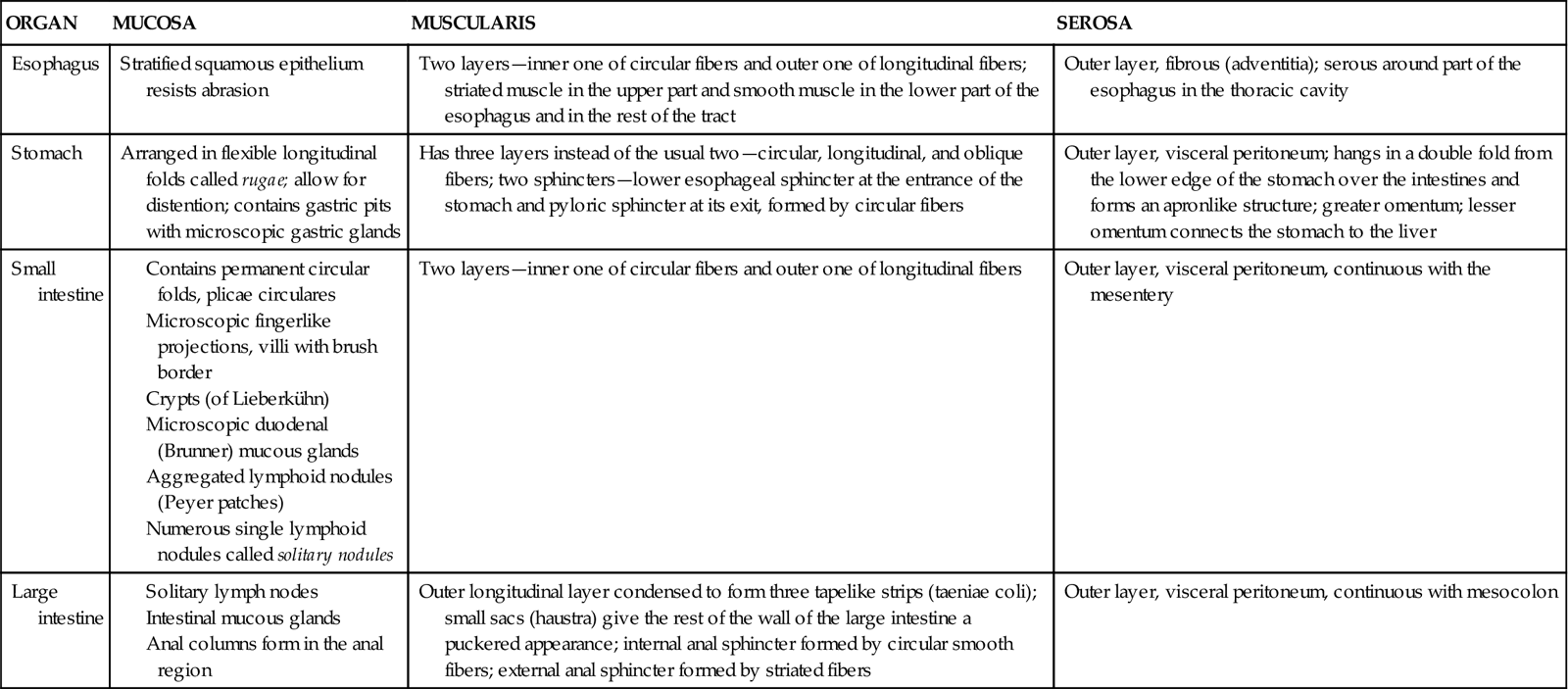

Although the same four tissue layers form the various organs of the GI tract, their structures vary in different regions of the tube throughout its length. Variations in the epithelial layer of the mucosa, for example, range from stratified layers of squamous cells that provide protection from abrasion in the upper part of the esophagus to the simple columnar epithelium, designed for absorption and secretion, which is found throughout most of the tract. Notice in Figure 28-2 that exocrine glands empty their secretions into the lumen of the GI tract through ducts. Some of these modifications are listed in Table 28-1; refer back to this table when each of these organs is studied in detail.

TABLE 28-1

Modifications of Layers of the Digestive Tract Wall

MOUTH

Structure of the Oral Cavity

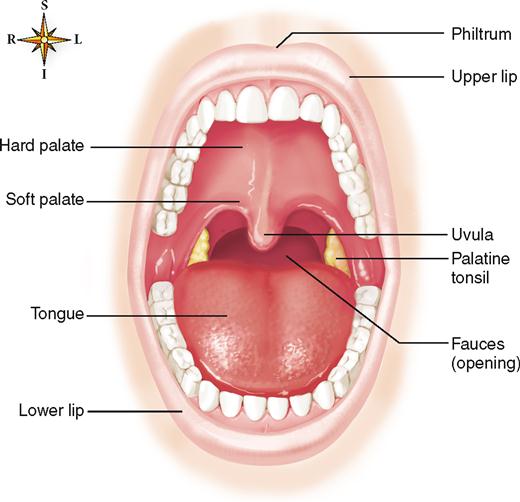

The mouth is also called the oral cavity. The following structures form the oral cavity (buccal cavity): the lips, which surround the orifice of the mouth and form the anterior boundary of the oral cavity, the cheeks (side walls), the tongue and its muscles (floor), and the hard palate and soft palate (roof) (Figure 28-3).

LIPS

The lips are covered externally by skin and internally by mucous membrane that continues into the oral cavity and lines the mouth. The junction between skin and mucous membrane is highly sensitive and easily irritated. The upper lip is marked near the midline by a shallow vertical groove called the philtrum, which ends at the junction between skin and mucous membrane in a slight prominence called the tubercle. The term fissure is often used to describe a cleft or groove between or separating anatomical structures. Therefore, when the lips are closed, the line of contact between them is called the oral fissure. Besides keeping food in the mouth while it is being chewed, the lips help sense the temperature and texture of food before it enters the mouth. The lips are also needed to form many speech sounds (syllables).

CHEEKS

The cheeks form the lateral boundaries of the oral cavity. They are continuous with the lips in front and are lined by mucous membrane that is reflected onto the gingiva, or gums, and the soft palate. The cheeks are formed in large part by the buccinator muscle, which is sandwiched with a considerable amount of adipose, or fat, tissue between the outer skin and mucous membrane lining. Numerous small mucus-secreting glands are located between the mucous membrane and the buccinator muscle; their ducts open opposite the last molar teeth.

HARD PALATE AND SOFT PALATE

The hard palate consists of portions of four bones: two maxillae and two palatines (see Figure 8-5. B on p. 205). The soft palate, which forms a partition between the mouth and nasopharynx (see Figure 26-3), is fashioned of muscle arranged in the shape of an arch. The opening in the arch leads from the mouth into the oropharynx and is named the fauces. Suspended from the midpoint of the posterior border of the arch is a small cone-shaped process, the uvula.

TONGUE

The tongue is a solid mass of skeletal muscle components (intrinsic muscles) covered by a mucous membrane.

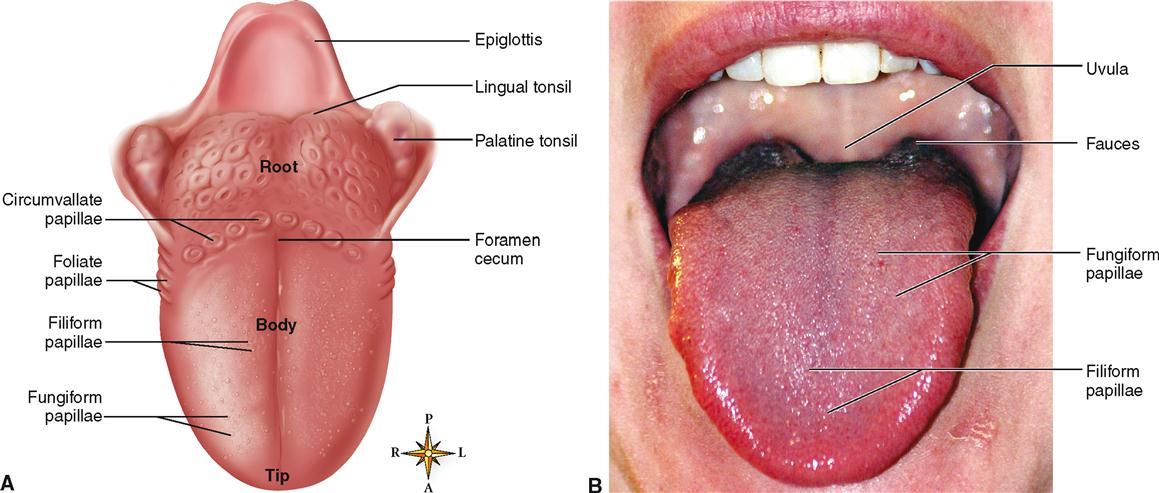

Note in Figure 28-4, A, that the tongue has a blunt root, a tip, and a central body. The upper, or dorsal, surface of the tongue is normally moist, pink, and covered by rough elevations, called papillae (Figure 28-4, B). Recall from Chapter 17 that papillae possess sensory organs called taste buds.

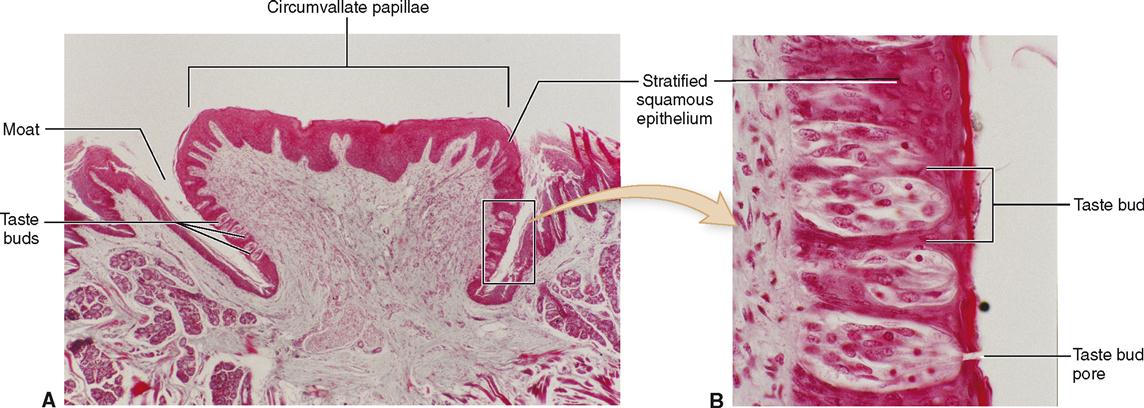

The four types of papillae—circumvallate, fungiform, foliate, and filiform—are all located on the sides or upper surface (dorsum) of the tongue. Note in Figure 28-4, A, that the large circumvallate papillae form an inverted V-shaped row extending from a median pit named the foramen cecum on the posterior part of the tongue. There are 10 to 14 of these large, mushroomlike papillae. You can readily distinguish them if you look at your own tongue. Figure 28-5 shows two micrographs of circumvallate papillae. To be tasted, a dissolved substance must enter a moatlike depression surrounding the papillae where it contacts taste buds located on the lateral surface.

Taste buds are also located on the sides of the fungiform papillae, which are found chiefly on the sides and tip of the tongue. Foliate papillae are leaflike ridges on the posterior, lateral edges of the tongue that also posses taste buds. The numerous filiform papillae are filamentous and threadlike in appearance. They have a whitish coloration and are distributed over the anterior two thirds of the tongue. Filiform papillae do not contain taste buds. Refer back to Chapter 17, p. 516, for more discussion of papillae and taste buds.

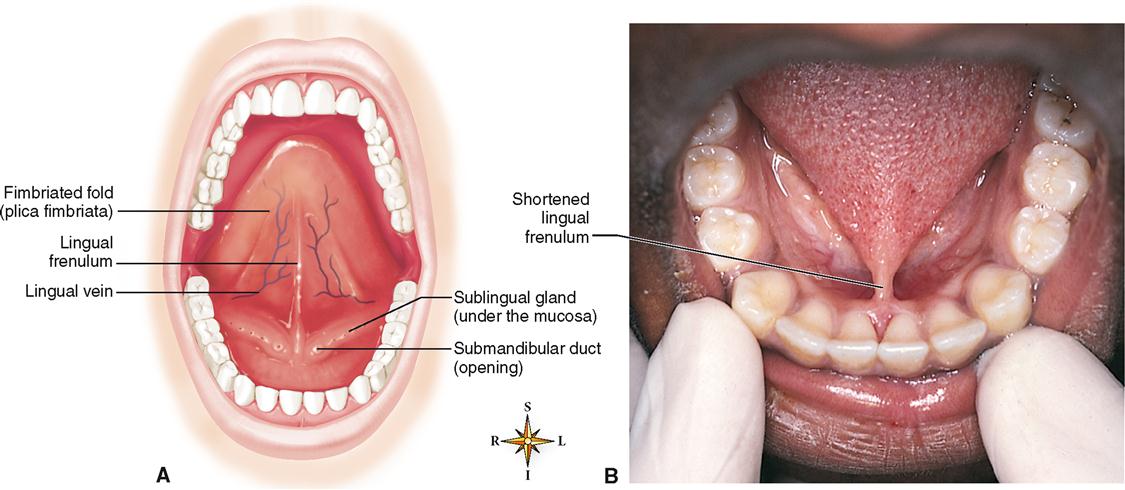

The lingual frenulum (Figure 28-6, A) is a fold of mucous membrane in the midline of the undersurface of the tongue that helps anchor the tongue to the floor of the mouth. If the frenulum is too short and hinders tongue movement—a congenital condition called ankyloglossia—the individual is said to be tongue-tied; this causes faulty speech (Figure 28-6, B).

A fold of mucous membrane called the fimbriated fold (or plica fimbriata) (see Figure 28-6, A) extends toward the apex of the tongue on either side of the lingual frenulum. The floor of the mouth and undersurface of the tongue are richly supplied with blood vessels. The deep lingual vein can be seen (see Figure 28-6, A) shining through the mucous membrane between the lingual frenulum and fimbriated fold. In this region many vessels are extremely superficial and are covered only by a very thin layer of mucosa. Soluble drugs, such as aspirin or nitroglycerin used during a heart attack, are absorbed into the circulation rapidly if placed under the tongue.

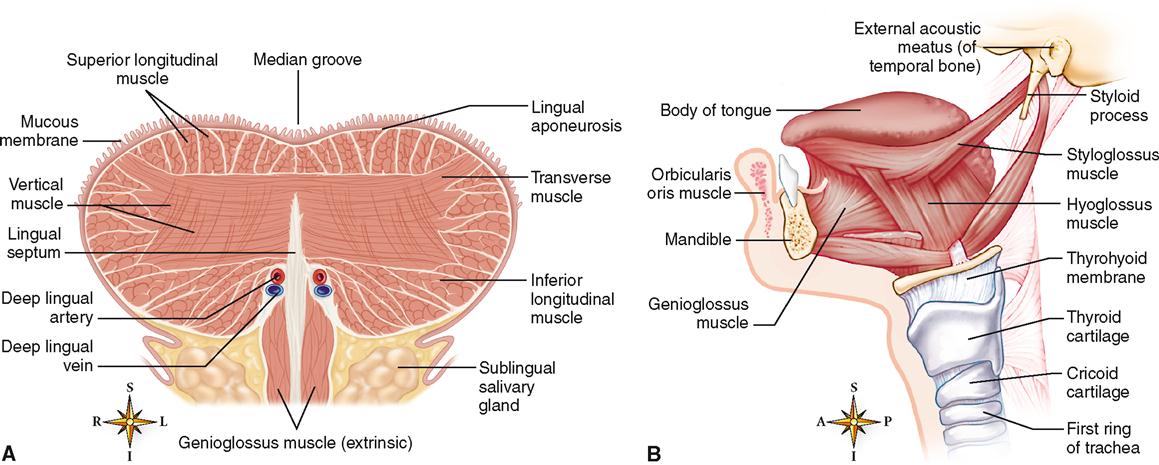

The intrinsic muscles of the tongue have, by definition, both their origin and their insertion in the tongue itself. As you can see in Figure 28-7, A, intrinsic muscles have their fibers oriented in all directions, thus providing a basis for extreme maneuverability. Changes in the size and shape of the tongue caused by intrinsic muscle contraction assist in placement of food material between the teeth during mastication (chewing). Such movements are also necessary for forming speech syllables properly.

Extrinsic tongue muscles are those that insert into the tongue but have their origin on some other structure, such as the hyoid bone or one of the bones of the skull. Examples of extrinsic tongue muscles are the genioglossus, which protrudes the tongue, and the hyoglossus, which depresses it (see Figure 28-7, B). Contraction of the extrinsic muscles is important during deglutition, or swallowing, and speech.

Salivary Glands

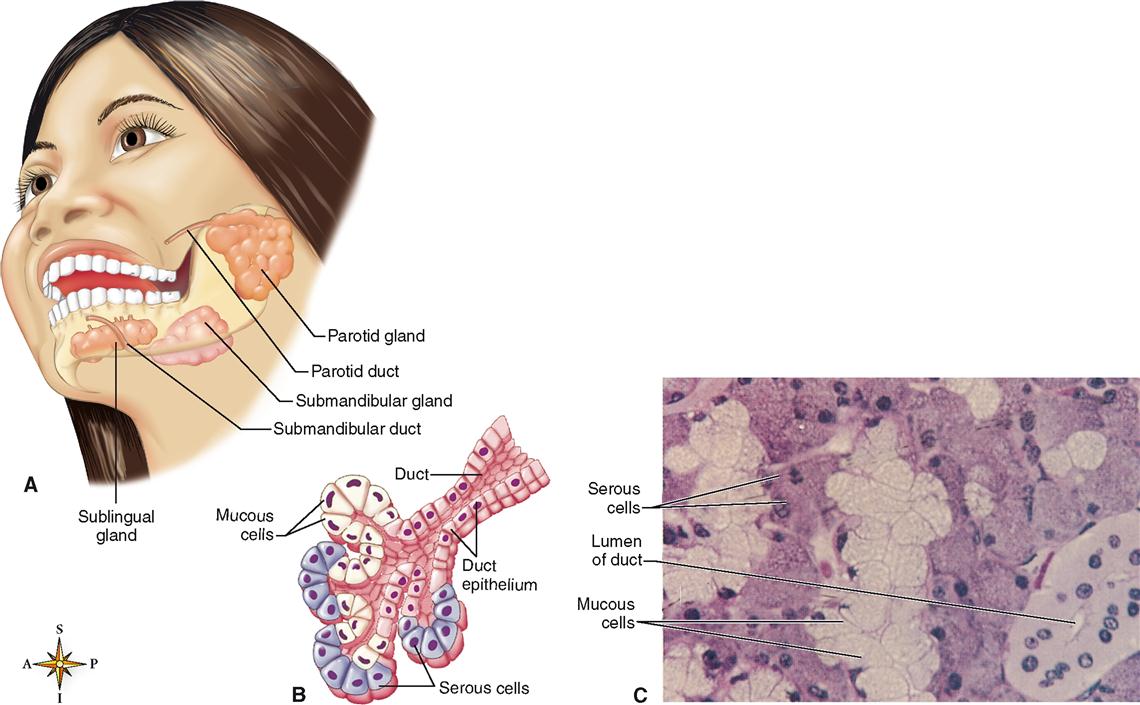

The salivary glands are typical of the accessory glands associated with the digestive system. They are located outside the alimentary canal and convey their exocrine secretions by way of ducts from the glands into the lumen of the tract (Figure 28-8, A). The mucous and serous cells seen in the compound tubuloalveolar gland pictured in Figure 28-8, B, together secrete a mixture of fluids that are then modified by the duct cells on their way out of the salivary gland. The functions of saliva in the digestive process are discussed in Chapter 29.

Three pairs of major salivary glands (see Figure 28-8)—the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands—secrete a major amount (about 1 liter) of the saliva produced each day. The minor salivary glands (buccal glands) that occur in the mucosa lining the cheeks and mouth contribute less than 5% of the total salivary volume. Buccal gland secretion is important, however, to the hygiene and comfort of the mouth tissues.

PAROTID GLANDS

The pyramidal parotids are the largest of the paired salivary glands (see Figure 28-8, A). They are located between the skin and underlying masseter muscle in front of and below the external ear. The parotids produce a watery, or serous, type of saliva containing enzymes but not mucus. The parotid (Stensen) ducts are about 5 cm (2 inches) long. They penetrate the buccinator muscle on each side and open into the mouth through the parotid papilla opposite the upper second molars. Inflammation of the parotids is called mumps or parotitis and is caused by paramyxovirus (see Mechanisms of Disease, p. 888).

SUBMANDIBULAR GLANDS

Submandibular glands (see Figure 28-8, A) are called mixed or compound glands because they contain both serous (enzyme) and mucus-producing elements (see Figure 28-8, B and C). These glands are located just below the mandibular angle. You can feel the gland by placing your index finger on the posterior part of the floor of the mouth and your thumb medial to and just in front of the angle of the mandible. The gland is irregular in form and about the size of a walnut. The ducts of the submandibular glands (Wharton ducts) open into the mouth on either side of the lingual frenulum.

SUBLINGUAL GLANDS

Sublingual glands are the smallest of the main salivary glands (see Figure 28-8, A). They lie in front of the submandibular glands, under the mucous membrane covering the floor of the mouth. Each sublingual gland is drained by 8 to 20 ducts (ducts of Rivinus) that open into the floor of the mouth. Unlike the other salivary glands, the sublingual glands produce only a mucous type of saliva.

Teeth

The teeth are the organs of mastication, or chewing. They are designed to cut, tear, and grind ingested food so that it can be mixed with saliva and swallowed. During the process of mastication, food is ground into small bits. This increases the surface area that can be acted on by the digestive enzymes.

TYPICAL TOOTH

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree