Anatomy of Cells

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY OF CELLS

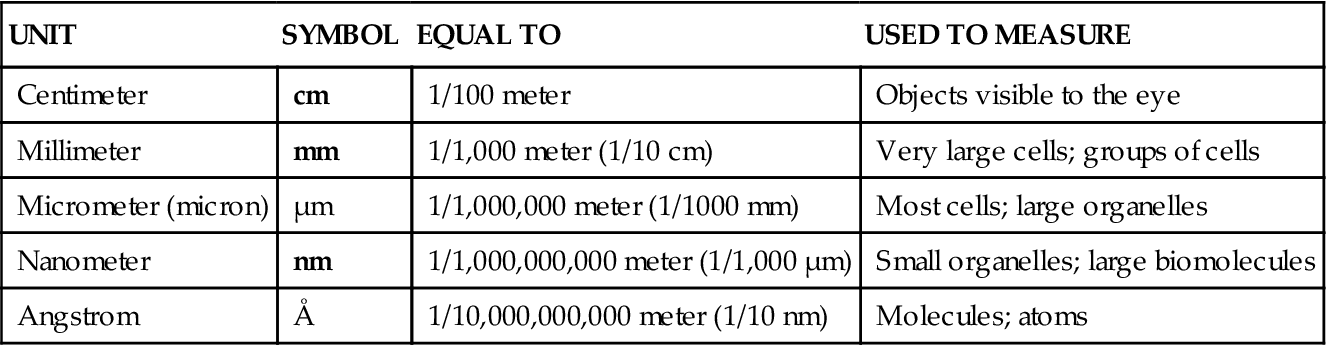

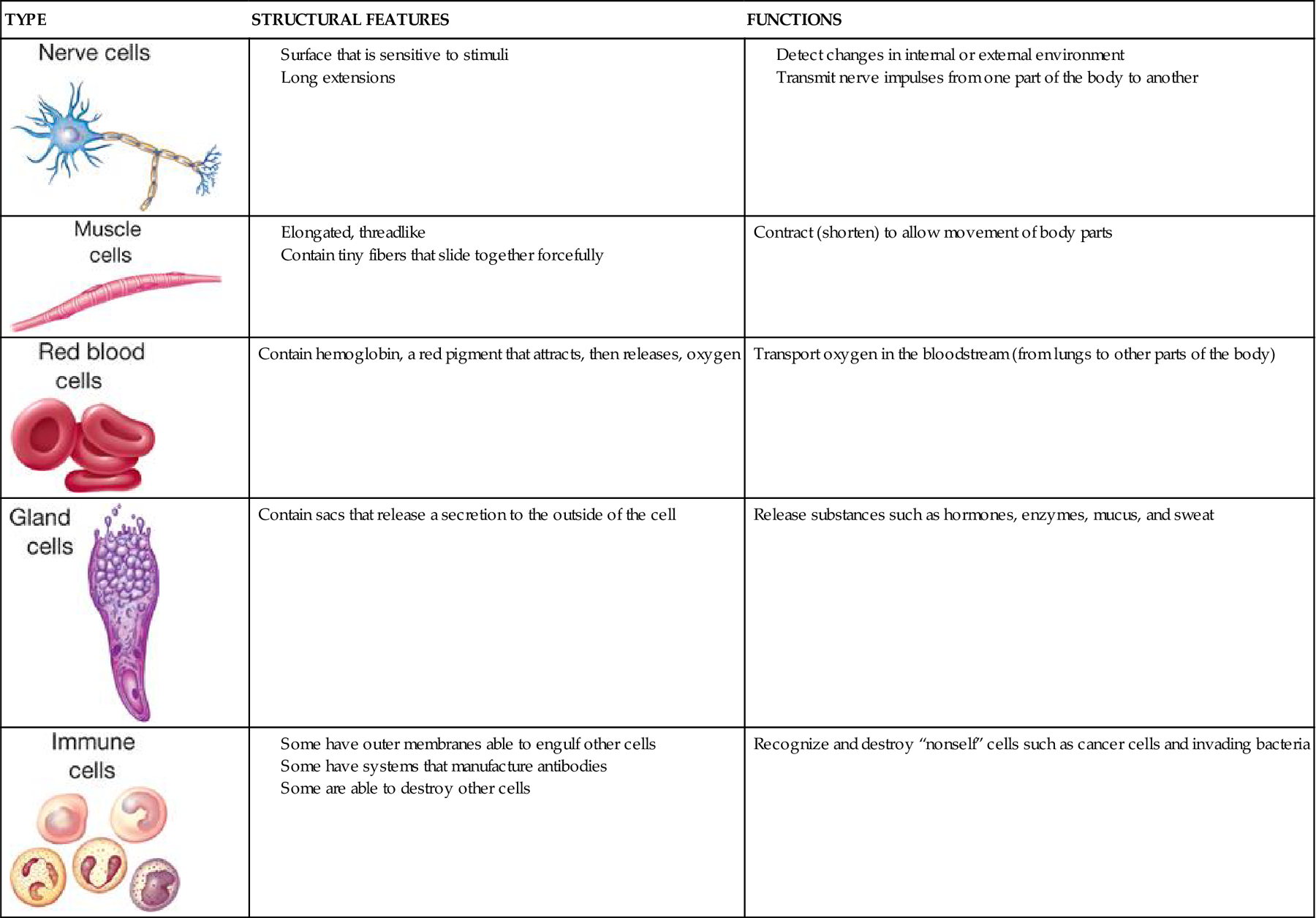

The principle of complementarity of structure and function was introduced in Chapter 1 and is evident in the relationships that exist between cell size, shape, and function. Almost all human cells are microscopic in size (Table 3-1). Their diameters range from 7.5 micrometers (μm) (example, red blood cells) to about 150 μm (example, female sex cell or ovum). The period at the end of this sentence measures about 100 μm—roughly 13 times as large as our smallest cells and two thirds the size of the human ovum. Like other anatomical structures, cells exhibit a particular size or form because they are intended to perform a certain activity. A nerve cell, for example, may have threadlike extensions over a meter in length! Such a cell is ideally suited to transmit nervous impulses from one area of the body to another. Muscle cells are adapted to contract, that is, to shorten or lengthen with pulling strength. Other types of cells may serve protective or secretory functions (Table 3-2).

TABLE 3-1

| UNIT | SYMBOL | EQUAL TO | USED TO MEASURE |

| Centimeter | cm | 1/100 meter | Objects visible to the eye |

| Millimeter | mm | 1/1,000 meter (1/10 cm) | Very large cells; groups of cells |

| Micrometer (micron) | μm | 1/1,000,000 meter (1/1000 mm) | Most cells; large organelles |

| Nanometer | nm | 1/1,000,000,000 meter (1/1,000 μm) | Small organelles; large biomolecules |

| Angstrom | Å | 1/10,000,000,000 meter (1/10 nm) | Molecules; atoms |

TABLE 3-2

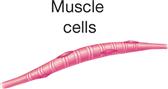

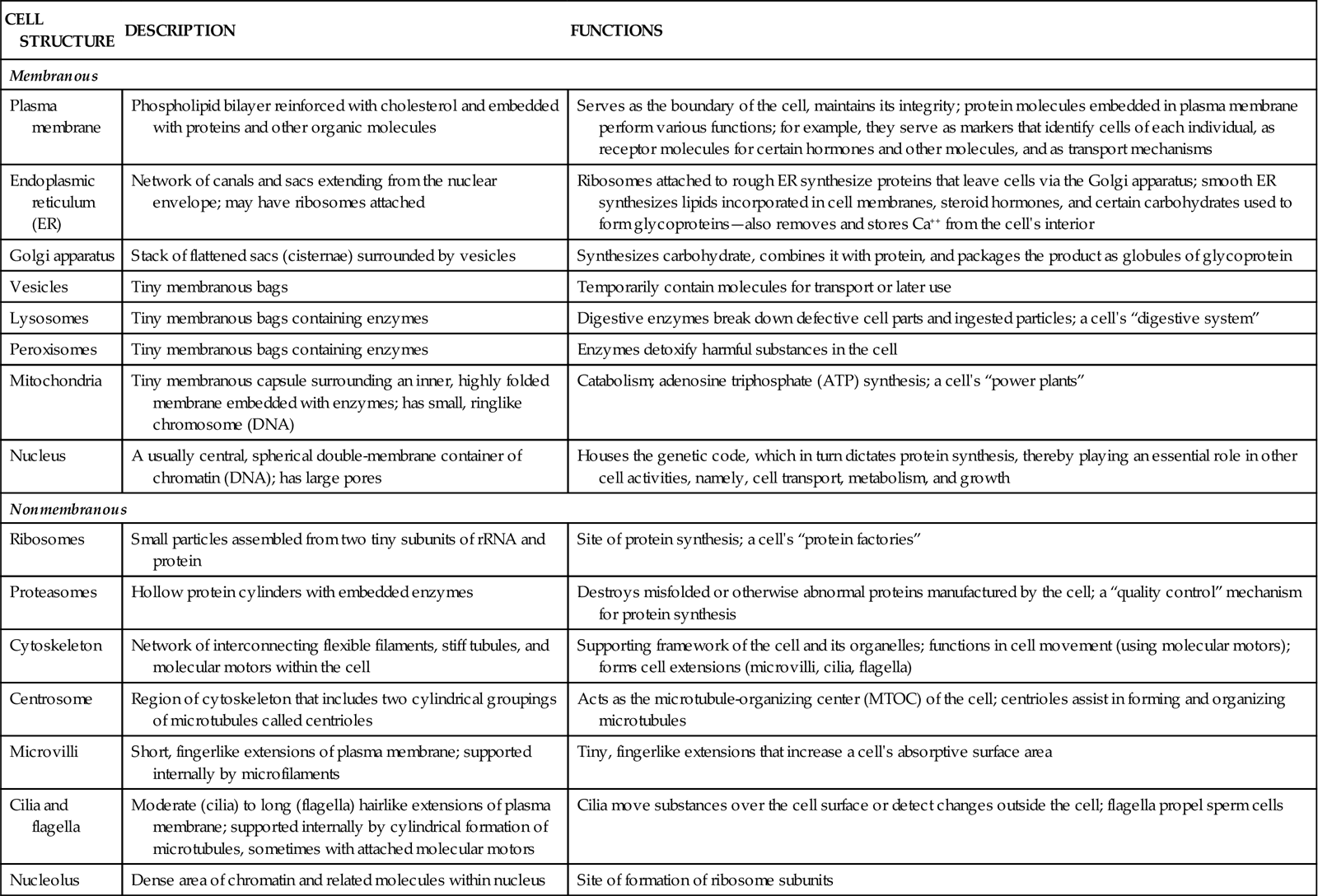

The Typical Cell

Despite their distinctive anatomical characteristics and specialized functions, the cells of your body have many similarities. There is no cell that truly represents or contains all of the various components found in the many types of human body cells. As a result, students are often introduced to the anatomy of cells by studying a so-called typical or composite cell—one that exhibits the most important characteristics of many different human cell types. Such a generalized cell is illustrated in Figure 3-1. Keep in mind that no such “typical” cell actually exists in the body; it is a composite structure created for study purposes. Refer to Figure 3-1 and Table 3-3 often as you learn about the principal cell structures described in the paragraphs that follow.

TABLE 3-3

Some Major Cell Structures and Their Functions

| CELL STRUCTURE | DESCRIPTION | FUNCTIONS |

| Membranous | ||

| Plasma membrane | Phospholipid bilayer reinforced with cholesterol and embedded with proteins and other organic molecules | Serves as the boundary of the cell, maintains its integrity; protein molecules embedded in plasma membrane perform various functions; for example, they serve as markers that identify cells of each individual, as receptor molecules for certain hormones and other molecules, and as transport mechanisms |

| Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) | Network of canals and sacs extending from the nuclear envelope; may have ribosomes attached | Ribosomes attached to rough ER synthesize proteins that leave cells via the Golgi apparatus; smooth ER synthesizes lipids incorporated in cell membranes, steroid hormones, and certain carbohydrates used to form glycoproteins—also removes and stores Ca++ from the cell’s interior |

| Golgi apparatus | Stack of flattened sacs (cisternae) surrounded by vesicles | Synthesizes carbohydrate, combines it with protein, and packages the product as globules of glycoprotein |

| Vesicles | Tiny membranous bags | Temporarily contain molecules for transport or later use |

| Lysosomes | Tiny membranous bags containing enzymes | Digestive enzymes break down defective cell parts and ingested particles; a cell’s “digestive system” |

| Peroxisomes | Tiny membranous bags containing enzymes | Enzymes detoxify harmful substances in the cell |

| Mitochondria | Tiny membranous capsule surrounding an inner, highly folded membrane embedded with enzymes; has small, ringlike chromosome (DNA) | Catabolism; adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis; a cell’s “power plants” |

| Nucleus | A usually central, spherical double-membrane container of chromatin (DNA); has large pores | Houses the genetic code, which in turn dictates protein synthesis, thereby playing an essential role in other cell activities, namely, cell transport, metabolism, and growth |

| Nonmembranous | ||

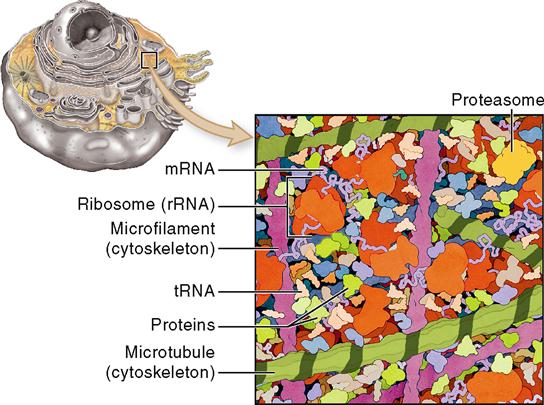

| Ribosomes | Small particles assembled from two tiny subunits of rRNA and protein | Site of protein synthesis; a cell’s “protein factories” |

| Proteasomes | Hollow protein cylinders with embedded enzymes | Destroys misfolded or otherwise abnormal proteins manufactured by the cell; a “quality control” mechanism for protein synthesis |

| Cytoskeleton | Network of interconnecting flexible filaments, stiff tubules, and molecular motors within the cell | Supporting framework of the cell and its organelles; functions in cell movement (using molecular motors); forms cell extensions (microvilli, cilia, flagella) |

| Centrosome | Region of cytoskeleton that includes two cylindrical groupings of microtubules called centrioles | Acts as the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) of the cell; centrioles assist in forming and organizing microtubules |

| Microvilli | Short, fingerlike extensions of plasma membrane; supported internally by microfilaments | Tiny, fingerlike extensions that increase a cell’s absorptive surface area |

| Cilia and flagella | Moderate (cilia) to long (flagella) hairlike extensions of plasma membrane; supported internally by cylindrical formation of microtubules, sometimes with attached molecular motors | Cilia move substances over the cell surface or detect changes outside the cell; flagella propel sperm cells |

| Nucleolus | Dense area of chromatin and related molecules within nucleus | Site of formation of ribosome subunits |

Cell Structures

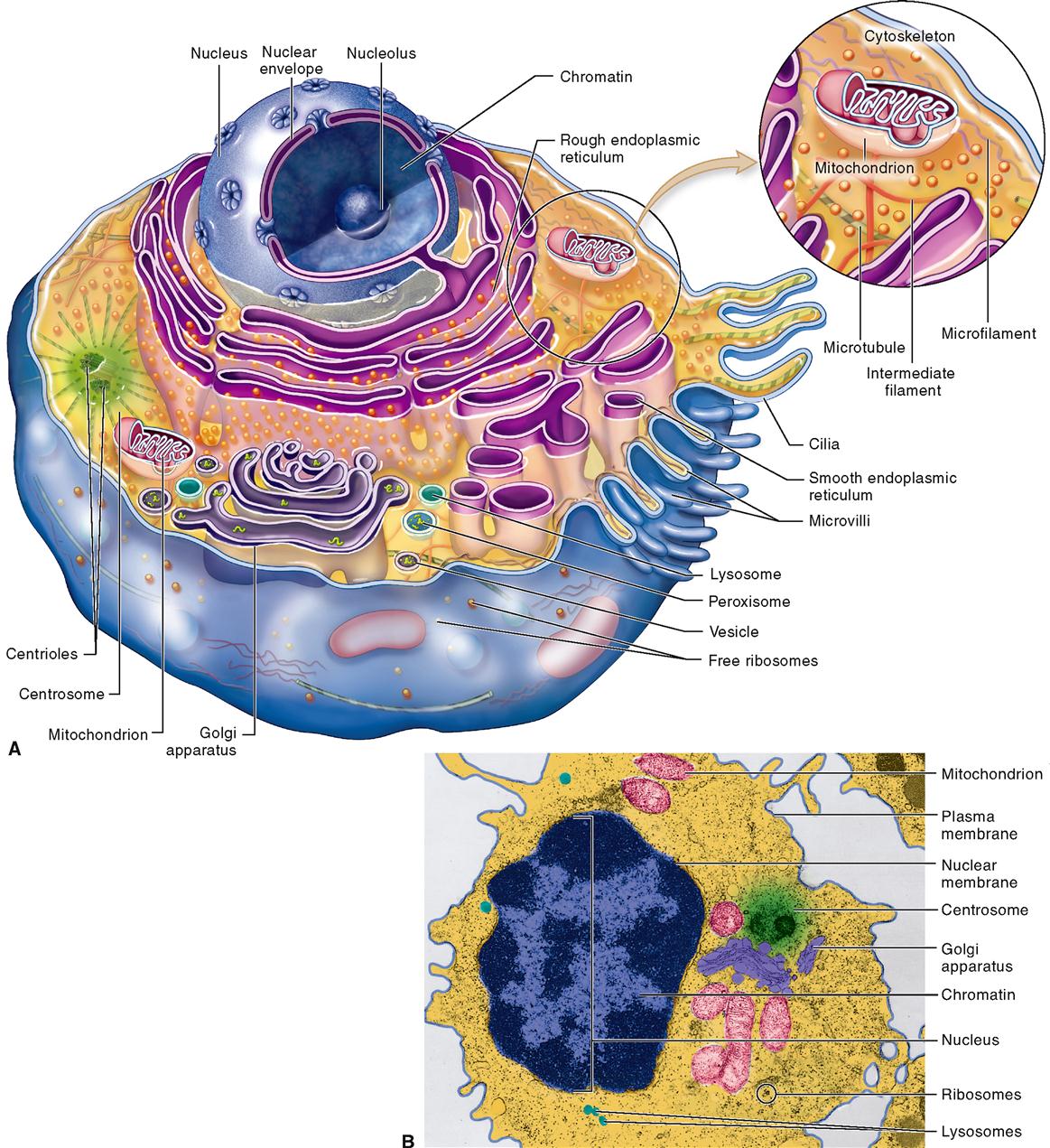

Ideas about cell structure have changed considerably over the years. Early biologists saw cells as simple, fluid-filled bubbles. Today’s biologists know that cells are far more complex than this. Each cell is surrounded by a plasma membrane that separates the cell from its surrounding environment. The inside of the cell is composed largely of a gel-like substance called cytoplasm (literally, “cell substance”). The cytoplasm is made of various organelles and molecules suspended in a watery fluid called cytosol, or sometimes intracellular fluid. As Figure 3-2 shows, the cytoplasm is crowded with large and small molecules—and various organelles. This dense crowding of molecules and organelles actually helps improve the efficiency of chemical reactions in the cell.

The nucleus, which is not usually considered to be part of the cytoplasm, is generally at the center of the cell. Each different cell part is structurally suited to perform a specific function within the cell—much as each of your organs is suited to a specific function within your body. In short, the main cell structures are (1) the plasma membrane; (2) cytoplasm, including the organelles; and (3) the nucleus (see Figure 3-1).

CELL MEMBRANES

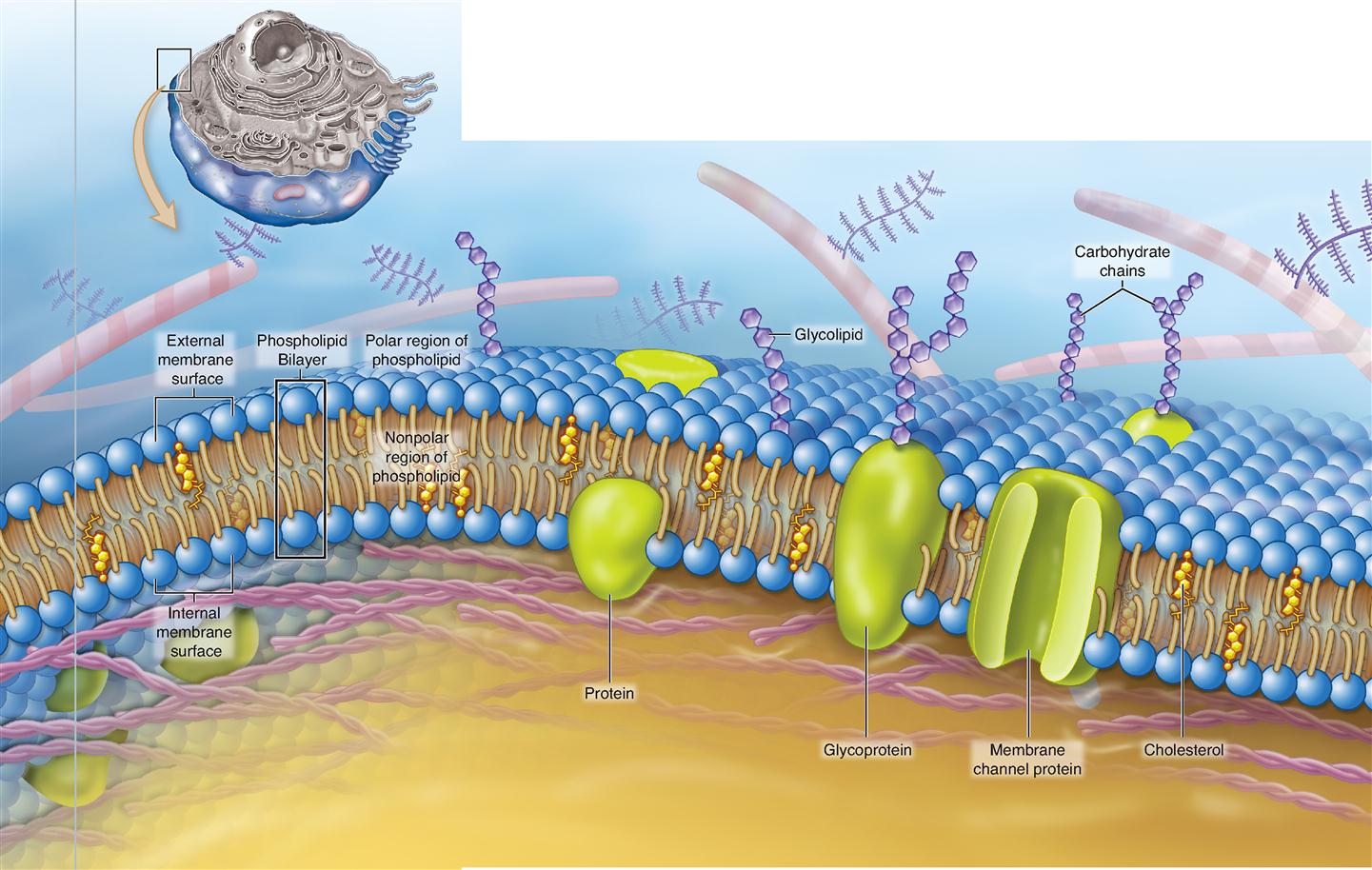

Figure 3-1 shows that a typical cell contains a variety of membranes. The outer boundary of the cell, or plasma membrane, is just one of these membranes. Each cell also has various membranous organelles. Membranous organelles are sacs and canals made of the same type of membrane material as the plasma membrane. This membrane material is a very thin sheet—averaging only about 75 angstroms (Å) or 0.0000003 inch thick—made of lipid, protein, and other molecules (Table 3-1).

Membrane Structure

Figure 3-3 shows a simplified view of the evolving model of cell membrane structure. This concept of cell membranes is called the fluid mosaic model. Like the tiles in an art mosaic, the different molecules that make up a cell membrane are arranged in a sheet. Unlike art mosaics, however, this mosaic of molecules is fluid; that is, the molecules are able to slowly float around the membrane like icebergs in the ocean. The fluid mosaic model shows us that the molecules of a cell membrane are bound tightly enough to form a continuous sheet but loosely enough that the molecules can slip past one another.

What are the forces that hold a cell membrane together? The short answer to that question is chemical attractions. The primary structure of a cell membrane is a double layer of phospholipid molecules. Recall from Chapter 2 that phospholipid molecules have “heads” that are water soluble and double “tails” that are lipid soluble (see Figure 2-21 on p. 49). Because their heads are hydrophilic (water loving) and their tails are hydrophobic (water fearing), phospholipid molecules naturally arrange themselves into double layers, or bilayers, in water. This allows all the hydrophilic heads to face toward water and all the hydrophobic tails to face away from water (see Figure 2-22 on p. 50).

Because the internal environment of the body is simply a water-based solution, phospholipid bilayers appear wherever phospholipid molecules are scattered among the water molecules. Cholesterol is a steroid lipid that mixes with phospholipid molecules to form a blend of lipids that stays just fluid enough to function properly at body temperature. Without cholesterol, cell membranes would break far too easily.

Each human cell manufactures various kinds of phospholipid and cholesterol molecules, which then arrange in a bilayer to form a natural “fencing” material of varying thickness that can be used throughout the cell. This “fence” allows many lipid-soluble molecules to pass through easily—just like a picket fence allows air and water to pass through easily. However, because most of the phospholipid bilayer is hydrophobic, cell membranes do not allow water or water-soluble molecules to pass through easily. This characteristic of cell membranes is ideal because most of the substances in the internal environment are water soluble. What good is a membrane boundary if it allows just about everything to pass through it?

Just as there are different fencing materials for different kinds of fences, cells can make any of a variety of different phospholipids for different areas of a cell membrane. For example, some areas of a membrane are stiff and less fluid; others are somewhat flimsy. Many cell membranes are packed more densely with proteins than seen in Figure 3-3; other membranes have less protein.

Some membrane lipids combine with carbohydrates to form glycolipids, and some unite with protein to form lipoproteins easily. Recall from Chapter 2 that proteins are made up of many amino acids, some of which are polar, some nonpolar (see Figure 2-26, p. 53). By having different kinds of amino acids in specific locations, protein molecules may become anchored within the bilayer of phospholipid heads and tails or attached to one side or the other of the membrane.

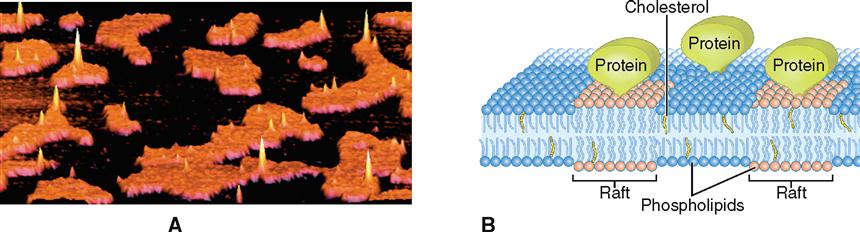

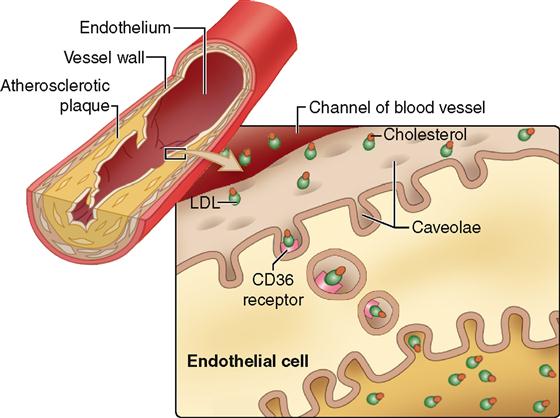

The different molecular interactions within the membrane allow the formation of lipid rafts, which are stiff groupings of membrane molecules (often very rich in cholesterol) that travel together like a log raft on the surface of a lake (Figure 3-4). Rafts help organize the various components of a membrane. Rafts play an important role in the pinching of a parent cell into two daughter cells during cell division. Rafts may also sometimes allow the cell to form depressions that pouch inward and then pinch off as a means of carrying substances into the cell (Box 3-1). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), for example, enters cells by first connecting to a raft protein in the plasma membrane and then subsequently being pulled into the cell.

Membrane Function

Embedded within the phospholipid bilayer are a variety of integral membrane proteins (IMPs). As their name implies, they are integrated into structure of the membrane itself. Proteins that have some functional regions or domains that are hydrophilic and other domains that are hydrophobic can be integrated into a phospholipid bilayer and remain stable. IMPs have many different structural forms that allow them to serve various functions (see Table 3-3).

A cell can control what moves through any section of membrane by means of IMPs that act as transporters (see Figure 3-3). Many of these transporters have domains forming openings that, like gates in a fence, allow water-soluble molecules to pass through the membrane. Specific kinds of transporterss allow only certain kinds of molecules to pass through—and the cell can determine whether these “gates” are open or closed at any particular time. We consider this function of integral membrane proteins again in Chapter 4 when we study transport mechanisms in the cell.

Some IMPs have carbohydrates attached to their outer surface—forming glycoprotein

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree