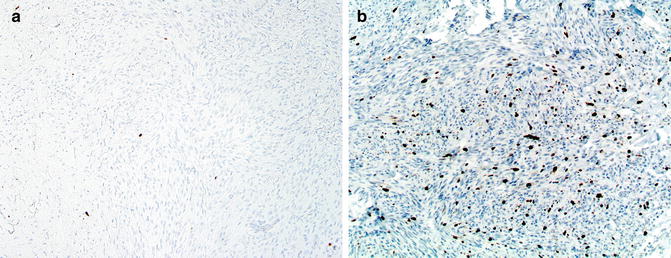

Fig. 4.1

Distinction between nevus and melanoma. (a) HMB45 labels the intraepidermal and upper dermal components of this large compound nevus. In contrast (b) melanoma cells show strong, but patchy labeling with HMB45, without showing the zonation change typical of nevi (HMB45, diaminobenzidine with light hematoxylin)

The two types of nevi that diverge from this pattern of maturation with HMB-45 are blue nevi (including cellular blue, plexiform, and “deep penetrating” nevi) and Spitz nevi, since both may show diffuse labeling with HMB-45 throughout the lesion. However, as with common nevi, these lesions show a very low proliferation rate as assessed with Ki67 expression (Fig. 4.2).

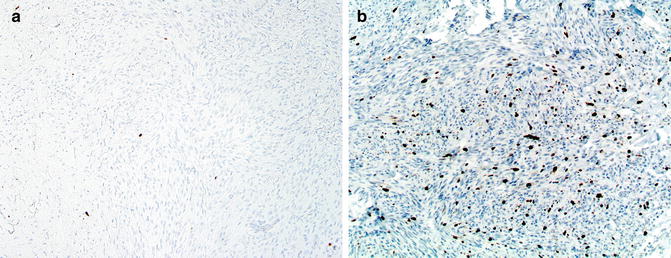

Fig. 4.2

Comparison of degree of proliferation between a large intradermal nevus and a melanoma. (a) The former has very rare cells in the dermis expressing Ki67. In contrast (b) melanoma cells typically have high rates of proliferation (anti-Ki67, diaminobencidine, with light hematoxylin)

The use of these two immunohistochemical markers may help also in the distinction between combined nevi and melanomas arising in association with a nevus. The most common scenario of a combined nevus is probably intradermal and blue. These combined nevi show low proliferation rates with anti-Ki67 (in both components) and display strong and diffuse labeling with HMB-45 in the blue nevus area only, while the standard intradermal nevus is negative. Similarly, immunohistochemistry may be helpful in delimiting the depth of invasion of melanomas arising in association with nevi (Fig. 4.3). In contrast with the associated dermal nevus, the invasive component of melanoma is usually positive with HMB-45 and has a higher percentage of Ki67-positive cells. Furthermore, by examining the pattern of expression of gp100 in a blue-nevus-type lesion it may be possible to distinguish primary blue-nevus-type melanoma from metastatic melanoma. A number of these melanomas resembling blue nevus (so-called malignant blue nevus) arise in association with a blue nevus. In such lesions, gp100 is strongly and diffusely expressed in the benign, preexistent blue nevus, while its expression becomes patchy in the malignant areas, along with increased Ki67 (see Chap. 10).

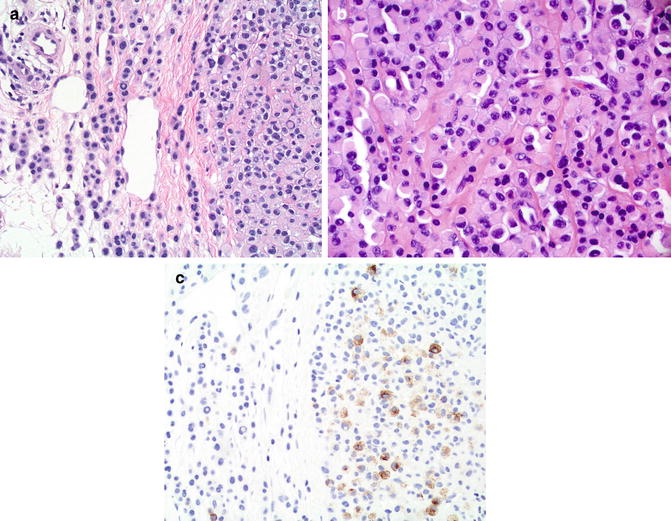

Fig. 4.3

Melanoma arising in association with a nevus; note the two different areas within the lesion. (a) This area shows benign-appearing melanocytes without significant cytologic atypia. (b) Other areas show atypical melanocytes. (c) HMB45 labels the atypical melanocytes (to the right) but not the benign melanocytes of the associated nevus (to the left) (HMB45, Diaminobenzidine and light hematoxylin as counterstain)

Possible Pitfalls of Immunohistochemistry Applied to the Diagnosis of Melanocytic Lesions

Some of the pitfalls to be included in this section also apply to other fields in pathology. Thus it is very important to determine that there is appropriate immunoreaction on the slide by observing the presence of both positive and negative internal controls. For instance, when examining a lesion for possible expression of MART1, it is necessary to examine the overlying epidermis and confirm that normal melanocytes are positive while keratinocytes are negative. Possible immunohistochemical pitfalls that we have observed are:

Decreased or absent expression of S100 protein [31]. As mentioned above, the antibody anti-S100 detects S100 protein in formalin-fixed tissue (since it requires cross-linkage). Therefore, it may not work in frozen sections. Also the antibody may not highlight consistently melanocytes in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of previously frozen tissue. Furthermore, if the tissue is over- or underfixed, S100 expression may be impaired (Fig. 4.4). Also, it has been suggested that S100 expression may be decreased in sun-damaged melanocytes [32].

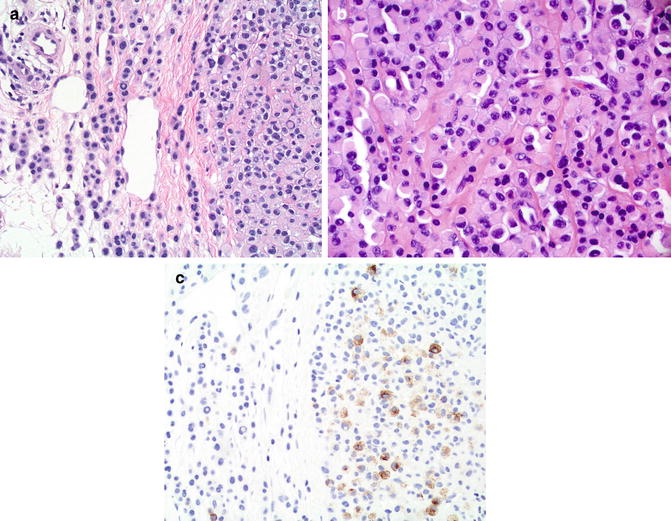

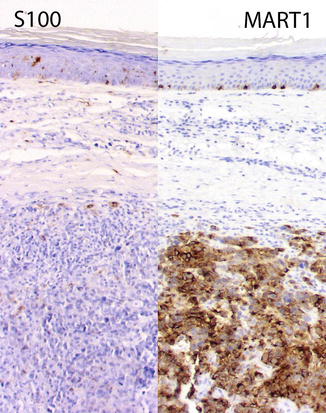

Fig. 4.4

Weak expression of S100 in a primary cutaneous melanoma likely due to fixation/processing reasons. To the left S100 only labels rare cells in the epidermis and dermis, likely dendritic cells. In contrast, note the strong expression of MART1 highlighting the intraepidermal melanocytes as well as the invasive component (anti-S100 protein and andi-MART1, DAB with light hematoxylin as counterstain)

Labeling of macrophages by anti-MART1 (and less frequently HMB-45) [12]. It is possible that current detection systems are more sensitive and may detect melanocytic antigens that have been phagocytized by macrophages.

Increased expression of gp100 (HMB-45 antigen) in benign melanocytic lesions. We have observed that the latest clones of HMB-45 appear to be more sensitive than the older ones. Dermatopathologists should be aware of this possibility; we recently reviewed a case that had been called metastatic melanoma to a sentinel lymph node, based upon the location (subcapsular and intraparenchymal) and reactivity with HMB-45 (see also the chapter on sentinel lymph nodes).

Summary

It is our opinion that immunohistochemistry has an important role in the diagnosis of melanocytic lesions. However, there is no single marker, or combination thereof, that establishes an unequivocal diagnosis of melanoma or nevus. Therefore, it is necessary to carefully analyze the pattern of expression (patchy versus diffuse) and localization/pattern of distribution (maturation) in the context of morphologic standard features.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree