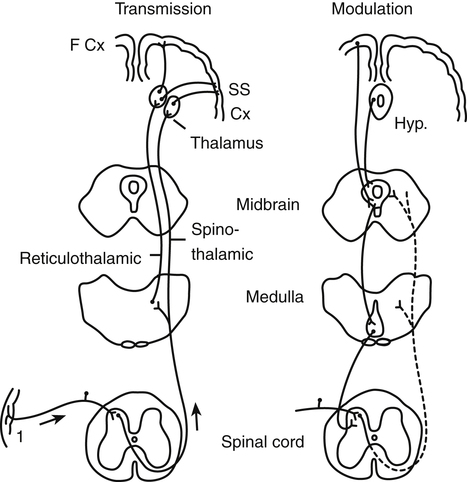

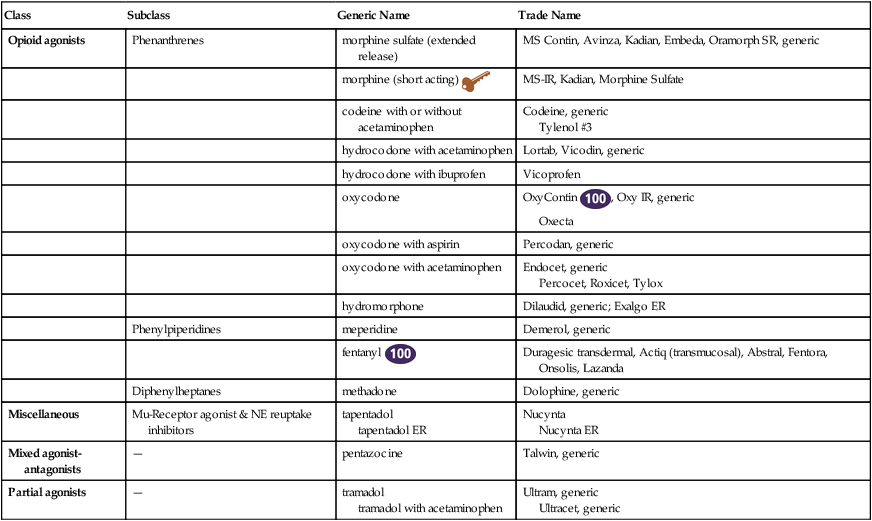

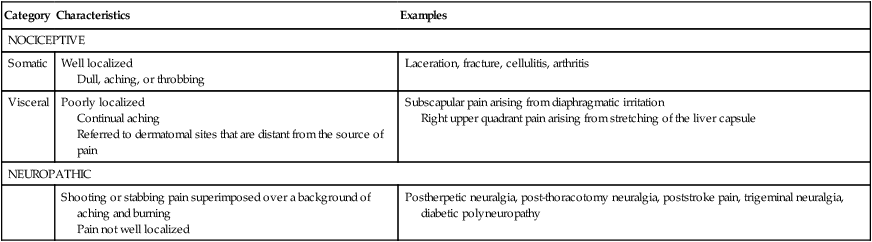

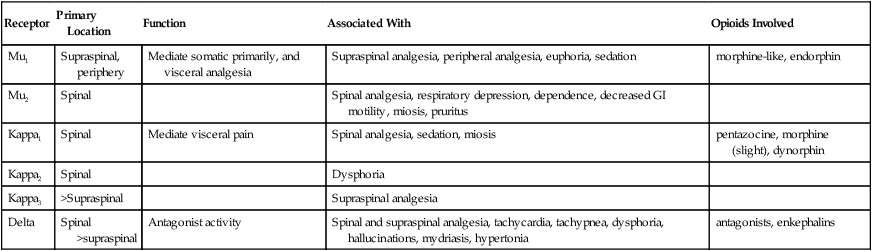

Chapter 43 Information about acetaminophen can be found in Chapter 35. Information about aspirin and NSAIDs can be found in Chapter 36. Synthetic opioids were developed in the hope of producing a less addictive drug. These attempts failed, but the drugs have proved to be extremely useful for management of both acute and chronic pain. Many semisynthetic derivatives are made through simple modifications of morphine or thebaine. Morphine is the precursor of the synthetic opioid analgesics hydrocodone, hydromorphone, and oxycodone. Thebaine is the precursor of naloxone, an opioid antagonist (see Chapter 50). The phenylpiperidines and the diphenylheptanes are chemical classes that are structurally distinct yet similar to morphine. These drugs have actions similar to those of morphine. The opioids are classified as narcotics and thus are considered controlled substances because of their abuse potential, as mandated by the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. Clinicians should be familiar with regulations regarding the use and dispensing of narcotic analgesics. Methadone is prescribed chiefly for the treatment of opiate detoxification and may be dispensed only by pharmacies and maintenance programs approved by the FDA and by state authorities, according to the requirements of the Federal Methadone Regulations. Methadone also is used for pain management; it may be prescribed by any provider with a DEA license to prescribe Schedule II drugs and can be dispensed by any licensed pharmacy (see Chapter 10). Because of the potential for abuse, the health care provider must justify the use of opioid analgesics for ambulatory patients. Next, transmission occurs, whereby electrical impulses are carried throughout the peripheral and CNS. Modulation is the central neural activity that controls the transmission of pain impulses. Finally, during perception, the neural activities involved in transmission and modulation result in a subjective correlate of pain that includes behavioral, psychologic, and emotional factors (Figure 43-1). Pain can be classified as nociceptive or neuropathic (Table 43-1). Nociceptive pain is further divided into two categories: somatic and visceral. Nociceptive pain arises from the direct stimulation of afferent nerves in cutaneous or deep musculoskeletal tissues. It occurs in response to tissue injury or disease infiltration of the skin, soft tissue, or viscera. Somatic pain is well localized in skin and subcutaneous tissues but not in bone, muscle, blood vessels, and connective tissue and is often described as dull or aching. Visceral pain is poorly localized and often is described as a continual aching, or a deep, crampy, or sharp, squeezing pain. Visceral pain may be referred to dermatomal or myotomal sites that are distant from the source of pain. Visceral pain occurs in response to stretching, distention, compression, or infiltration of organs such as the liver. TABLE 43-1 • Ask about pain at every office visit or phone call. • Assess pain systematically. (Be consistent in using the same pain intensity scales for pain measurement.) • Believe the patient and family regarding their reports of pain and what relieves it. • Choose pain control options that are appropriate for the patient, family, and setting. • Delivery of pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic interventions should be made in a timely, logical, and coordinated fashion. • Empower patients and their families. • Enable them to control their course to the greatest extent possible. Actions of opioid analgesics can be defined by their activity at three specific receptor types: mu, kappa, and delta. The mu receptors mediate morphine-like supraspinal analgesia, miosis, respiratory depression, euphoria, physical dependence, and suppression of opiate withdrawal. The kappa receptors mediate spinal analgesia, respiratory depression, and sedation. The delta receptors mediate antagonist activity (Table 43-2). Morphine-like agonists have activity at the mu, kappa, and delta receptors. Mixed agonist-antagonist drugs, such as pentazocine, have agonist activity at some receptors and antagonist activity at other receptors. The opioid antagonist naloxone does not have agonist activity at any opioid receptors. TABLE 43-2 Action of Opioids on Pain Receptor Sites • Gruener D, Lande SD, editors: Pain control in the primary care setting, Glenview, IL, 2006, American Pain Society. (Available at www.ampainsoc.org)www.ampainsoc.org. • Chou R et al: Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain, The Journal of Pain 10(2):113-130, 2009. Available at www.ampainsoc.org. • American Pain Society: Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain, Glenview, IL, 2003. • Qaseen A et al: Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians, Ann Intern Med 148(2):141-146, 2008. • Chou R, Huffman LH, American Pain Society, American College of Physicians: Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline, Ann Intern Med 147:505-514, 2007. • Lorenz KA: Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review, Ann Intern Med 148:147-159, 2008. • Some evidence suggests that long-term management of chronic pain with opiates may significantly improve functional outcomes and quality of life. • Morphine is effective in providing relief of moderate to severe pain but is associated with the adverse effects of constipation, nausea, and vomiting. • Limited evidence suggests that there is very little difference between hydromorphone and other opioids in terms of analgesic efficacy, adverse effects, and patient preference. • Limited evidence indicates that methadone is effective for relief of cancer pain, and it is available for administration via multiple routes. • Randomized, controlled trials conducted to support the practice of switching opioids to manage inadequate pain relief and intolerable side effects are lacking. • To avoid problems with prescribing opioids, the provider must follow federal and state regulations and commonly accepted guidelines. • Chronic pain requires routine administration of drugs. Giving medication before pain is severe means that the patient will use less of the drug. The clinician should instruct that medication is to be given regularly without waiting until the patient is in severe pain and is begging for medication. Long-acting preparations should be considered for patients with chronic pain. • Experts agree that addiction generally is not a concern, especially for patients with chronic pain or terminal illness. Primary care providers should be comfortable about treating patients who have chronic pain. Pain of greater severity may be relieved by combining therapies. More severe pain may require the addition of an opioid preparation that is useful at higher dosages. Analgesic adjuvants may be useful. Frequent follow-up is needed to assess outcomes and side effects, provide reassurance, and establish goals. It is unrealistic to expect total pain relief in patients with chronic pain. Concurrent problems such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia augment the perception of pain in many patients. • The variety of patients who present with pain is extensive, and treatment should be individualized to the patient’s response. Acute mild to moderate pain, such as that seen with strains and sprains, is commonly managed in the primary care setting. Acute severe pain usually is managed in an acute care setting to address the underlying cause, such as acute myocardial infarction or fracture. Chronic pain, both benign and malignant, is managed in primary care or by referral to specialty pain management clinics. Hospice referral is important for the management of pain and other symptoms associated with terminal disease and dying. Because of reimbursement mechanisms and changes in practice, pain management is being moved increasingly from the purview of the specialist to the primary care setting. • Patients with chronic pain may have multiple problems, including psychiatric responses to chronic pain and other comorbid conditions. Simply prescribing a pill is not an effective way to manage pain. These patients require a comprehensive pain management program that includes the patient, the family, and caregivers, along with all health care providers, including specialists. The plan must be consistent from one health professional to the next. Primary care clinicians may have to refer patients to pain management clinics for evaluation and specialized treatment, such as nerve block. Hospice referral must be considered for terminal conditions. • A 2011 CDC report revealed that more than 40 people die each day due to overdoses of prescription painkillers, such as Vicodin, methadone, Opana, and OxyContin, that are routinely prescribed for medical or dental problems. Painkiller overdoses causing death have more than tripled in a decade. Clinicians should carefully assess patients before giving prescriptions and when patients return for follow-up care and more medication. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that 1 in 20 people aged 12 and older claimed they had used prescription painkillers for nonmedical reasons in 2010. • For adequate treatment of pain, the cause first must be identified, and then management of the underlying disease must be maximized. Refer the patient to appropriate specialists and members of the interdisciplinary team, such as orthopedists, neurosurgeons, psychiatrists, pain specialists, physical and occupational therapists, or hospice staff, for further evaluation and additional interventions. Provide the patient with education regarding the nature of pain, assessment tools (e.g., use of pain scales and pain diaries), and the purposes and expected results of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management. To reduce anxiety, allow the patient to have some control over the situation and to make decisions when possible. • Nonpharmacologic treatment of pain can be used alone or in combination with medications. Nonpharmacologic measures include patient education, management of anxiety and depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and appropriate exercise and activity. Common cognitive-behavioral interventions include distraction, meditation, and progressive relaxation therapy. Expressive therapies such as art, music, and movement therapy also have proved effective. Complementary and alternative medicine therapies may be helpful, although little scientific evidence is available to support the use of chiropractic manipulation, homeopathy, and spiritual healing. Heat, ice, massage, topical analgesics, acupuncture, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may provide relief when used alone or in combination with analgesic medications. • Whenever possible for mild to moderate pain, begin pharmacologic pain management with acetaminophen (see Chapter 35) on an around-the-clock schedule if the patient has not yet tried this regimen. The maximum dose for patients without renal or hepatic dysfunction or alcohol use is 4000 mg/day given in divided doses. If acetaminophen is not effective, an NSAID (see Chapter 36) can be used. The combined use of NSAIDs and acetaminophen is unlikely to improve pain relief. NSAIDs have a side effect of GI bleeding; in addition, they elevate blood pressure, cause fluid retention, and may provoke renal failure, particularly in the elderly. • If nonopioid medications are not effective or are not tolerated, opiates can be given alone or with acetaminophen for nonmalignant and malignant pain. Dosage may depend on whether the patient is opiate naive. Fear of drug dependency or addiction does not justify withholding of opiates or inadequate management of pain. Advise patients regarding side effects and driving. Prophylactically treat constipation. Obtain an informed consent before initiating therapy. Discuss goals, expectations, potential risks, and alternative therapies. The goal of therapy must be clearly stated and should not be complete elimination of pain. Consider a written plan with an exit strategy. The patient should have only provider-prescribed opioids and should get them from only one pharmacy. Document carefully in the patient chart. • Adjuvant drugs, which are medications developed for purposes other than analgesia, use different pain pathways in reducing pain. They are particularly useful for neuropathic pain when given alone or in combination with NSAIDs or opioids. Gabapentin and other, newer anticonvulsants are good first-line choices and have fewer side effects than the older tricyclic antidepressants (Table 43-3). Serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as paroxetine (Paxil) have not been effective in pain relief, while serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as duloxetine (Cymbalta) have proved effective. TABLE 43-3

Analgesia and Pain Management

Class

Subclass

Generic Name

Trade Name

Opioid agonists

Phenanthrenes

morphine sulfate (extended release)

MS Contin, Avinza, Kadian, Embeda, Oramorph SR, generic

morphine (short acting) ![]()

MS-IR, Kadian, Morphine Sulfate

codeine with or without acetaminophen

Codeine, generic

Tylenol #3

hydrocodone with acetaminophen

Lortab, Vicodin, generic

hydrocodone with ibuprofen

Vicoprofen

oxycodone

OxyContin ![]() , Oxy IR, generic

, Oxy IR, generic

Oxecta

oxycodone with aspirin

Percodan, generic

oxycodone with acetaminophen

Endocet, generic

Percocet, Roxicet, Tylox

hydromorphone

Dilaudid, generic; Exalgo ER

Phenylpiperidines

meperidine

Demerol, generic

fentanyl ![]()

Duragesic transdermal, Actiq (transmucosal), Abstral, Fentora, Onsolis, Lazanda

Diphenylheptanes

methadone

Dolophine, generic

Miscellaneous

Mu-Receptor agonist & NE reuptake inhibitors

tapentadol

tapentadol ER

Nucynta

Nucynta ER

Mixed agonist-antagonists

—

pentazocine

Talwin, generic

Partial agonists

—

tramadol

tramadol with acetaminophen

Ultram, generic

Ultracet, generic

Therapeutic Overview

Pathophysiology

Disease Process

Classification of Pain

Category

Characteristics

Examples

NOCICEPTIVE

Somatic

Well localized

Dull, aching, or throbbing

Laceration, fracture, cellulitis, arthritis

Visceral

Poorly localized

Continual aching

Referred to dermatomal sites that are distant from the source of pain

Subscapular pain arising from diaphragmatic irritation

Right upper quadrant pain arising from stretching of the liver capsule

NEUROPATHIC

Shooting or stabbing pain superimposed over a background of aching and burning

Pain not well localized

Postherpetic neuralgia, post-thoracotomy neuralgia, poststroke pain, trigeminal neuralgia, diabetic polyneuropathy

Assessment

Mechanism of Action

Opioid Agonists

Receptor

Primary Location

Function

Associated With

Opioids Involved

Mu1

Supraspinal, periphery

Mediate somatic primarily, and visceral analgesia

Supraspinal analgesia, peripheral analgesia, euphoria, sedation

morphine-like, endorphin

Mu2

Spinal

Spinal analgesia, respiratory depression, dependence, decreased GI motility, miosis, pruritus

Kappa1

Spinal

Mediate visceral pain

Spinal analgesia, sedation, miosis

pentazocine, morphine (slight), dynorphin

Kappa2

Spinal

Dysphoria

Kappa3

>Supraspinal

Supraspinal analgesia

Delta

Spinal >supraspinal

Antagonist activity

Spinal and supraspinal analgesia, tachycardia, tachypnea, dysphoria, hallucinations, mydriasis, hypertonia

antagonists, enkephalins

Treatment Principles

Standardized Guidelines

Evidence-Based Recommendations

Cardinal Points of Treatment

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

Pharmacologic Treatment

Drug Class

Indications

Comments

Examples

Anticonvulsants

Neuropathic pain from diabetic neuropathy, trigeminal neuralgia, postherpetic neuralgia, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, and neuralgia from nerve trauma or cancer infiltration

Especially useful for episodic lancing or burning pain

clonazepam

gabapentin

pregabalin

Neuroleptics

Chronic pain syndromes, moderate to severe pain unrelieved by opioids, or the presence of severe side effects with use of opioids

Antiemetic and anxiolytic effects

chlorpromazine

Tricyclic antidepressants

Neuropathic pain, including postherpetic neuralgia and neuropathy

These drugs have innate analgesic properties and may potentiate the analgesic effects of opioids.

Anticholinergic side effects

amitriptyline

nortriptyline

Serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

Pain from diabetic neuropathy

Only drug of its class that is FDA approved for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy

duloxetine ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Analgesia and Pain Management

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue