Alterations in the Integumentary System

Lee-Ellen C. Copstead, Ruth E. Diestelmeier and Michael R. Diestelmeier

Key Questions

• How does the aging process affect the integumentary system?

• Why is it important to differentiate primary from secondary skin lesions?

• What lesion characteristics are assessed to aid in determination of the lesion’s cause?

• How do systemic disorders affect nail and hair growth?

• How does ultraviolet radiation affect the skin?

• How do superficial and deep pressure ulcers differ in clinical and etiologic features?

• How can malignant melanoma be differentiated from other skin lesions?

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Copstead/

This chapter focuses on altered structure and function of the integumentary system. The etiologic factors, pathogenesis, and clinical manifestations of selected skin disorders as well as general considerations regarding treatment modalities and their therapeutic application are described.

Age-Related Changes

The skin undergoes dramatic changes from birth through the mature years. Healthy infants and young children have relatively smooth and unwrinkled skin characterized by elasticity and flexibility. Because skin tissues are in an active phase of new growth, healing of skin injuries is often rapid and efficient. Young children and elderly individuals have fewer sweat glands than adults do, so their bodies rely more on increased blood flow to maintain a normal body temperature.

As adulthood begins at puberty, hormones stimulate the development and activation of sebaceous glands and sweat glands. After the sebaceous glands become active, especially during the initial years, they may overproduce sebum and thus give the skin an unusually oily appearance. Sebaceous ducts may become clogged or infected and form acne pimples or other blemishes on the skin. Activation of apocrine sweat glands during puberty causes increased sweat production, an ability needed to maintain an adult body properly, and also the possibility of increased “body odor.” Body odor is caused by wastes produced by bacteria that feed on the organic compounds found in apocrine sweat and on the surface of the skin.

Past early adulthood and into middle age, the sebaceous and sweat glands become less active. Although this can provide relief to those who suffer from acne or other problems associated with overactivity of these glands, it can affect the normal function of the body. For example, the reduction in sebum production can cause the skin and hair to become less resilient.

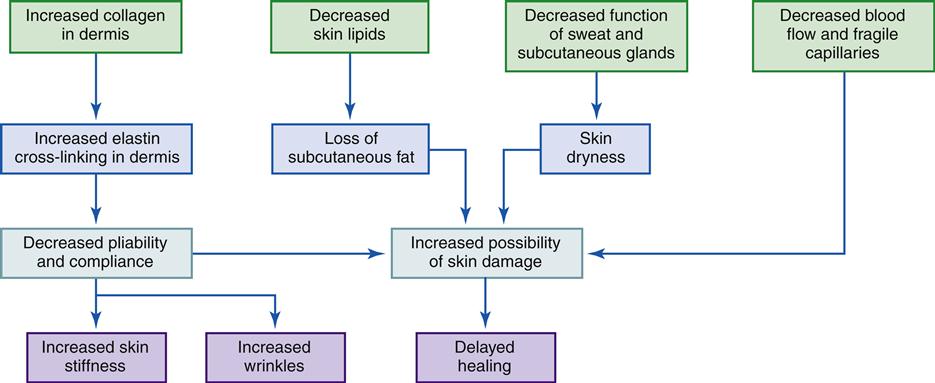

Changes in the appearance and function of the skin, perhaps more than in any other organ, reflect the continual aging process (see Geriatric Considerations: Changes in the Integumentary System). One need only look at a person to determine an approximate age. Evidence of advancing age includes wrinkling and sagging skin, gray hair, and baldness. Aging changes are also linked to environmental influences, genetic makeup, and other bodily changes (Figure 53-1).

Exposure to sunlight is one of the greatest factors in age-related skin changes. The result of such exposure can be seen in people who work outdoors in sunlight. Results are also evident when skin exposed to sunlight is compared with unexposed skin. Skin that is usually covered shows little change with age. Blue-eyed, fair-skinned individuals are more susceptible to solar skin damage than are people with darker, more heavily pigmented skin.

Epidermis

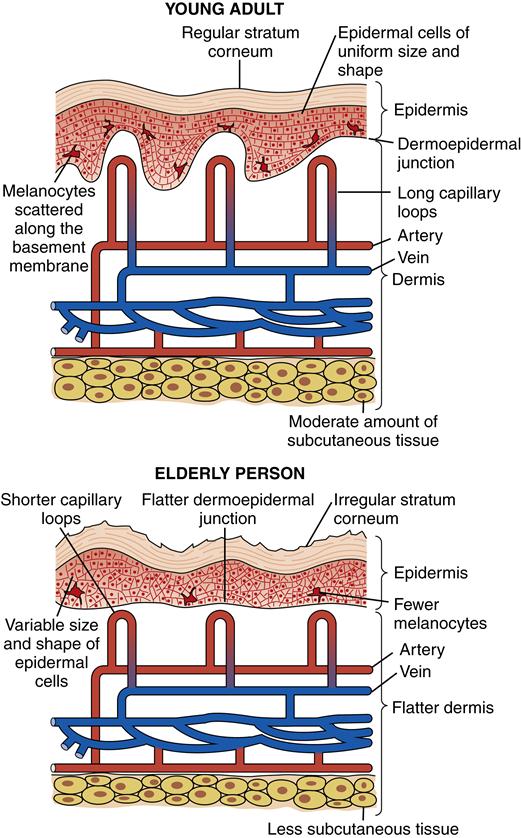

The epidermis shows a generalized thinning with advancing age, although there may be some thickening in sun-exposed areas. Although there is an increased variation in epidermal thickness, the average number of cell layers remains unchanged. The prickle cells of the inner layer of the epidermis show greater variation in nuclear and cytoplasmic size with a less orderly arrangement of cells. Cells reproduce more slowly and are larger and more irregular; however, exposed epidermal cells may divide more frequently than unexposed cells.

Dermis and Subcutaneous Tissue

The dermis contains blood vessels, nerves, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands, but the major portion is composed of collagen and elastin. The elasticity of the skin is largely due to dermal elastin. Decreased skin strength and elasticity with aging are attributed to a decreased amount of elastin and a proportionate increase in the collagen-to-elastin ratio. Collagen fibers change with age, becoming cross-linked and rearranged into thicker bundles. This condition is called elastosis and is closely associated with exposure to sunlight (solar elastosis). It produces a weather-beaten or tanned appearance.

Aging also produces a decrease in the vascularity of the dermal skin, as evidenced by decreasing numbers of epithelial cells and blood vessels. There is greater vascular fragility, leading to the frequent appearance of hemorrhages (senile purpura); cherry angiomas; venous stasis; and venous lakes on the ears, face, lips, and neck. The decreased vascularity and circulation in the dermis and the underlying subcutaneous tissue also have an effect on drug absorption. Drugs administered subcutaneously are absorbed more slowly, thus prolonging their half-life. The amount of subcutaneous fat tissue also decreases, especially in the extremities, so that arms and legs appear to be thinner.

Appendages

Hair

The most obvious change in aging hair is its color. Half of the population over age 50 years has at least 50% gray body hair, regardless of gender or hair color. Gray hair is determined by an autosomal dominant gene and results from a decreased rate of melanin production by the hair follicle. Hair color generally darkens with age, but this process is reversed with the onset of graying. Graying usually begins at the temples of the head and extends to the vertex of the scalp. It may not occur in the axilla, especially in women, and occurs to a lesser extent in the presternum or the pubis.

Changes in hair growth and distribution are also associated with aging. The amount and distribution of hair are determined by racial, genetic, and sex-linked factors; however, almost all older people have a diminution of body hair except on the face. Adults develop a full terminal hair pattern by age 40 years, and this is followed by a progressive loss of hair in reverse order of development. Postmenopausal Caucasian women lose trunk hair first, then pubic and axillary hair. Unopposed adrenal androgens produce coarse facial hair in 50% of Caucasian women older than 60 years, especially on the chin and around the lips.

Men also show a general thinning of hair distribution, with the hairs of the eyebrows, ears, and nose becoming longer and coarser. Baldness is often a concern, particularly in aging men, although women also tend to show some thinning of scalp hair. Frontal recession of the hairline occurs in 80% of older women and 100% of older men. Baldness in men is inherited from the mother and occurs only in the presence of testosterone. Onset is variable and is manifested by an M-shaped pattern of hair loss on either side of the midline or by a thinning patch over the vertex.

In general, the hair of both men and women changes from darker, thicker, and more numerous to lighter, thinner, and less numerous with aging. Hair changes begin in midlife and become highly noticeable in later life, especially after age 60 years. Women seem to manifest more hair loss on the trunk and extremities, whereas men have greater hair loss on the head.

Nails

With aging, nails become dull, brittle, hard, and thick. Most nail changes are due to a diminished vascular supply to the nail bed. There is approximately a 30% to 50% decrease in the growth rate of fingernails, from 0.1 mm/day in 30 year olds to 0.07 mm/day in 90 year olds. Aging nails show an increase in longitudinal striations, which can cause splitting of the nail surface.

Toenails are particularly prone to hyperkeratosis and resultant thickening. Pressure and trauma from poorly fitting footwear may be a significant factor, but onychomycosis, which affects approximately 20% of individuals over age 60, is the primary factor.1

Glands

Sebaceous glands show little atrophy or histologic change with age; however, their function tends to diminish, as evidenced by a decrease in sebum secretion. In men the decrease is minimal, but in women there is a gradual diminution in sebum secretion after menopause, with no significant changes after the seventh decade. There are fewer sebaceous glands in older individuals, which appear related to the loss of hair follicles. The decrease in sebum secretion and in the number of sebaceous glands results in the drier, coarser skin associated with aging.

Sweat glands generally decrease in size, number, and function with age. In the eccrine glands, the secretory epithelial cells become uneven in size, ranging from normal to small, and there is a progressive accumulation of lipofuscin in the cytoplasm. In the very old, the secretory coils of many eccrine glands are replaced by fibrous tissue, which drastically diminishes their capacity to produce sweat. The thermal threshold for sweating is raised, so that the amount of sweat output at a body temperature of 38° C (100.4° F) decreases. This may be due to the fact that there are fewer blood vessels and nerve cells around the glands that enable the body to respond to temperature changes. Apocrine glands do not decrease in number or size, but they do decrease in function. An accumulation of lipofuscin has also been noted in apocrine glands. The diminished functioning of sweat glands in the elderly greatly impairs the ability to maintain body temperature homeostasis.

Box 53-1 summarizes the morphologic features of aging human skin, and Figure 53-2 summarizes the histologic changes associated with aging in normal human skin.

Evaluation of the Integumentary System

A careful examination of the skin yields valuable information that may aid in identifying a systemic disease or a specific problem of the skin or appendages. Diagnostic evaluations include a careful history, and Table 53-1 provides a general guide. A proper skin examination also describes the objective signs of dermatologic disease, including all types of lesions and their distribution.

TABLE 53-1

SUMMARY OF KEY ASSESSMENT ITEMS

| ASSESSMENT ITEM | PURPOSE AND RELEVANT QUESTIONS TO ASK |

| Family history | Some skin diseases are familial or hereditary. When hereditary skin disease is ascertained, one may have the opportunity to both correct misconceptions and allay fears about the presence, absence, or prognosis of disease. What are the current familial dermatologic diseases? |

| Personal history | What was the age at onset of the problem? How has the patient adjusted to the problem? By social withdrawal? Cosmetic cover-up? Withdrawal from school athletic activities that require showers (e.g., football, tennis)? Does the problem threaten the patient’s self-image of masculinity or femininity? What is the patient’s ethnic origin? (Some skin diseases are more common in certain ethic groups.) |

| Geographic origin and present abode | Length of time spent living in each area? Some skin diseases are indigenous, which may be important because of increased exposure. Occasionally, a contact of only 5 min is all that is necessary for acquisition of a disease. |

| Season | Seasonal occurrence of a problem? Pollen? Sunlight? |

| Occupation | Type of work? Skin contact material (e.g., chemicals, dust, gas), excessive heat and abnormal lighting, unhygienic surroundings, possible infective insects, other family members’ occupational exposures? |

| Leisure activities | Does the problem occur only on weekends? After yard activities? Painting? Woodworking? Camping? Fishing? Hiking? In association with children’s play? |

| Accompanying diseases | Collagen disease? Drug therapy for collagen disease? Other diseases and their drug therapy? |

| Previous treatment | Self-treatment? Other drugs prescribed? |

| Special history | Onset of skin lesions (abnormality)? Remissions, exacerbations, or recurrences? Site of onset? Character of lesions? Original character and subsequent changes? Course or extension? Symptoms? Itching? Ability to perform duties? Topical therapy? Self-treatment? Psychological factor? What does the patient associate with exacerbations of the problem (e.g., stress of a family argument, tax time, report time)? |

Data from Rosen T et al, editors: Nurse’s atlas of dermatology, Boston, 1983, Little, Brown.

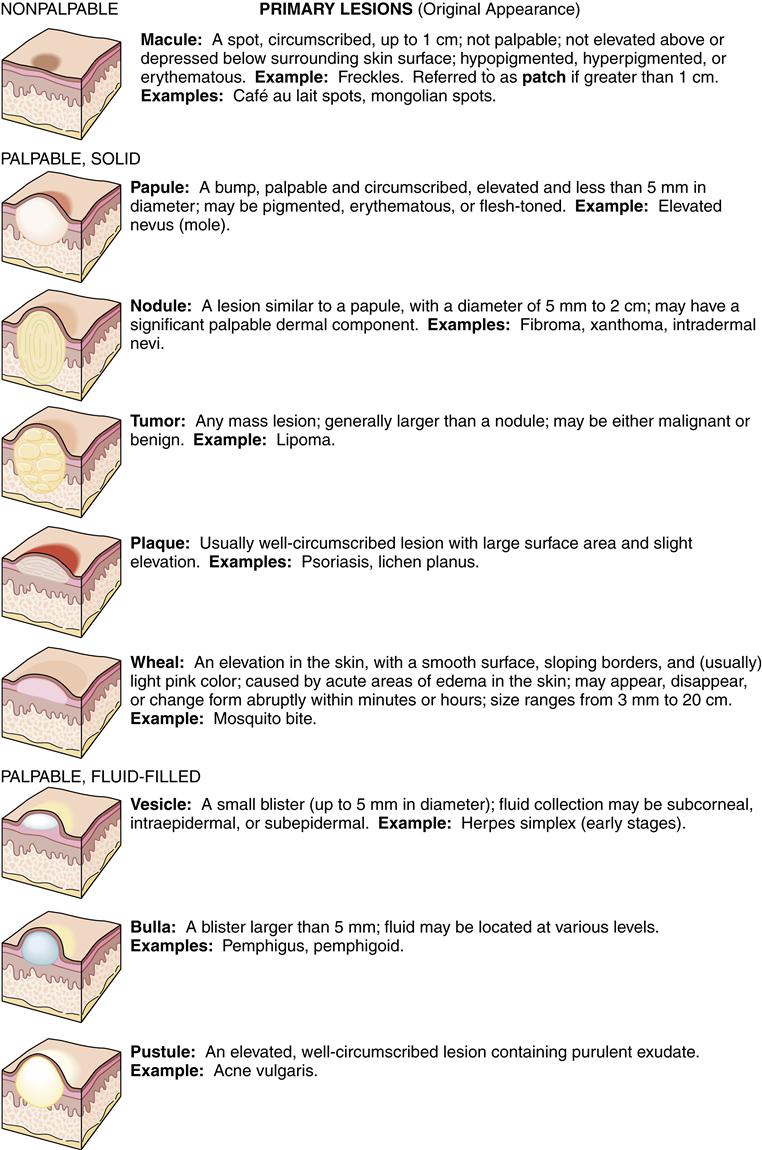

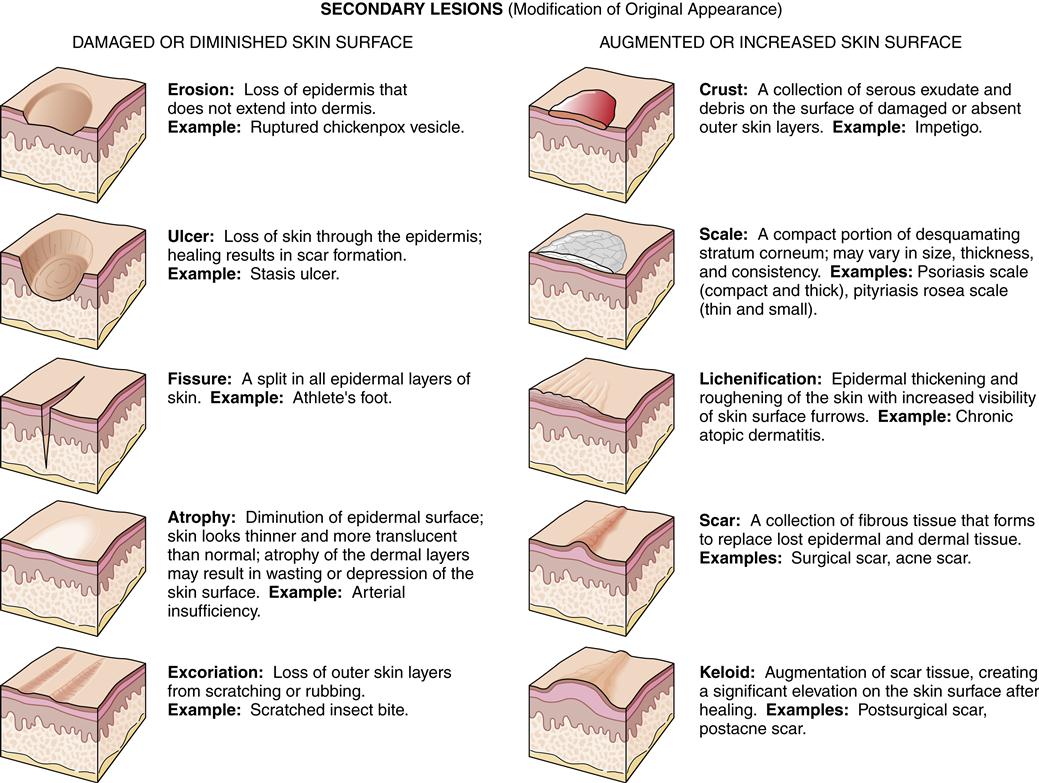

Primary and Secondary Lesions

Physical descriptions should include the lesions and their classification, generally primary (original appearance) or secondary (appearance modified by normal progress over time or by such external agents as scratching). Figure 53-3 shows clinical examples of primary and secondary lesions.

Lesion Descriptors

After a skin lesion has been classified as primary or secondary, other features should be noted, particularly size, symmetry of color and shape, and distribution if more than one lesion is present. Skin lesions may assume a wide range of colors—red–salmon pink, brown-black, blue-purple, bone white–slate gray, and yellow, to name a few. Each color suggests certain diagnoses. Skin lesions may be solitary, few, or profuse. When more than one lesion is present, the distribution pattern may be important in suggesting the diagnosis. Look for the following common patterns: symmetric (affecting mirror-image portions of the body), sun-exposed (affecting skin sites that routinely receive solar irradiation), intertriginous (affecting warm, moist, apposed skin sites), acral (affecting the distal extremities, ears, and nose), genital, and flexor or extensor predominance. Additional descriptors are often used to further characterize and describe a skin lesion or the relationship between various skin lesions such as confluent or clustered. Table 53-2 lists common morphologic and configurational terms.

TABLE 53-2

| TERM | DEFINITION |

| Confluent | Blending together |

| Diffuse | Generalized or widespread |

| Discrete | Remaining separate but close together |

| Eczematous | Vesicles with an oozing crust |

| Herpetiform | Closely grouped vesicles (herpeslike) |

| Linear | Set in a straight line |

| Localized | Found only in one area |

| Pedunculated | On a stalk |

| Reticulated | Netlike array |

| Round lesions | Annular (ring shaped, active edge, clear center) |

| Arcuate (arc shaped, incomplete circle) | |

| Circinate (circular) | |

| Guttate (small droplet–like) | |

| Iris (concentric circles such as a bull’s eye) | |

| Nummular (coin shaped) | |

| Ovoid (oval shaped) | |

| Serpiginous | Wandering, snakelike |

| Telangiectatic | Characterized by dilated surface vessels |

| Verrucous | Rough, wartlike surface |

| Zosteriform | Similar to shingles, following along a nerve root dermatome |

Data from Sauer GC: Manual of skin diseases, ed 6, Philadelphia, 1991, Lippincott.

Selected Skin Disorders

Diseases of the skin are divisible into two broad etiologic categories: inflammatory/infectious and proliferative/neoplastic. Inflammatory disorders of the skin often occur in individuals who have hypersensitivity reactions to substances in the environment. Infectious agents ranging from viruses to insects may infect the skin. Proliferative conditions include psoriasis, seborrheic keratosis, cysts, warts, and papillomas. Other benign tumors arise from other cells in the skin: nevi, lipomas, dermatofibromas, neuromas, and hemangiomas. Kaposi sarcoma is a malignant, opportunistic neoplasm that occurs in persons with preexisting immunodeficiency.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States; however, with the exceptions of malignant melanoma and a few squamous carcinomas, skin cancers are not life threatening. Ultraviolet light damages sun-exposed skin and is a major factor in development of skin cancer. Although many of the disorders described in the following section are not life threatening, they can affect the quality of life.

Infectious Processes

Viral Infections

Verrucae

Etiology and pathogenesis

Verrucae, or warts (Figure 53-4), are common benign papillomas caused by DNA-containing papillomaviruses. Although warts vary in appearance depending on their location, the histologic characteristics of all lesions are similar. A wart is actually an exaggeration of normal skin composition, with the stratum corneum being irregularly thickened. The human papillomaviruses, the subgroup of papovaviruses that causes human warts, are not found in other animals and invade only the skin and mucous membranes of humans.

Warts may resolve spontaneously if immunity to the virus develops, but the immune response can be delayed for years and is not reliably activated in every case. In 95% of cases, untreated warts will resolve within 5 years,2 but they may multiply into hundreds of lesions and can involve any body site. Current surgical treatment may be directed at removal of the wart by laser. Liquid nitrogen or acid chemicals, cryotherapy, and salicylic acid paint or plasters have also been effective medical treatments. Topical blistering agents, immunomodulators, and intralesional injections of various agents may also be effective treatment modalities.

Herpes Simplex Virus

Etiology and pathogenesis

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections of the skin and mucous membranes are common (Figure 53-5). Two types of herpesviruses infect humans: type 1 and type 2. Most HSV-1 infections occur above the waist.3 HSV-1 may result when external infection is spread to the other parts of the body through the occupational hazards that exist in professions such as dentistry and medicine and some athletics. HSV-2 is responsible for most infections in the genital region.3

Herpesvirus lesions usually begin with a burning or tingling sensation. Vesicles and erythema follow and progress to pustules, ulcers, and crusts before healing. The lesion is most common on the lips, face, and mouth. Pain is common, and healing takes place in 10 to 14 days.4 After the initial infection, the herpesvirus persists in latent form in the trigeminal nerve and other ganglia. Recurrent lesions are common and may be precipitated by stress, sunlight exposure, menses, or injury.5,6 The vast majority of patients have at least 1 episode of herpesvirus reactivation, and some individuals may have 10 or more outbreaks per year. Recently, concern has arisen over the identification of infectious viral shedding in the absence of symptomatic lesions.5

Treatment

No cure for herpes simplex is known, and most treatment measures are palliative. Lidocaine (Xylocaine) or diphenhydramine (Benadryl) application and aspirin administration help relieve pain. Cold compresses help in the acute stages. Acyclovir, famciclovir, or valacyclovir is recommended to shorten the duration of active disease outbreaks; in certain situations, these drugs may be used for daily prophylaxis.

Herpes-Zoster Virus

Etiology and pathogenesis

Herpes zoster (shingles) is an acute localized inflammatory disease of a dermatomal segment of the skin (Figure 53-6). It is caused by the same herpesvirus that causes chickenpox (varicella-zoster virus). It is believed to be the result of reactivation of a latent varicella-zoster virus that has been present in the sensory dorsal ganglia since childhood infection. During an attack of shingles, the reactivated virus travels from the ganglia to the skin of the corresponding dermatome.

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations of shingles include the eruption of vesicles with erythematous bases that are restricted to skin areas supplied by sensory neurons of a single or associated group of dorsal root ganglia. Eruptions generally follow a unilateral dermatomal distribution and most often occur on the thorax, trunk, and face. In immunosuppressed persons, the lesions may extend beyond the dermatome. New crops of vesicles erupt for 3 to 5 days along the nerve pathway.3 Lesions are deeper and more confluent than those of chickenpox. The vesicles dry, form crusts, and eventually fall off. Lesions usually clear in 2 to 3 weeks.3 Severe pain and paresthesias are common. In the elderly, herpes-zoster virus is a particularly serious condition that may be long lasting. Pain reports from elderly individuals indicate an increased severity and lengthy episodes of up to 1 year.3 Systemic treatment with acyclovir, famciclovir, or valacyclovir should be initiated as soon as possible, preferably within the first 48 to 72 hours.

Postherpetic neuralgia is the most important complication occurring in people older than 50 years.3 Eye involvement can result in permanent blindness.

Treatment

Management of shingles includes oral antiviral drugs; acyclovir (Zovirax) is one example. Topical agents such as Burow compresses or aqueous alcohol shake lotions may also be used. Pain medication may be indicated in severe cases. Systemic corticosteroids have also been effective in healthy persons older than 50 years with severe pain, but their use remains controversial. High doses of interferon, an antiviral glycoprotein, have been used in persons with cancer when the herpetic lesions are limited to the dermatome.7

Additionally, vaccination is becoming an important tool in preventing herpes zoster (e.g., Zostavax).

Fungal Infections

Superficial Fungal Infections

Three genera of fungi (dermatophytes) commonly infect human skin: Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton. These organisms can cause an infection termed tinea in any cutaneous area, including the hair and nails. Infections in different locations are named after the location: tinea capitis (scalp) (Figure 53-7, A), tinea barbae (beard), tinea faciei (face) (Figure 53-7, B), tinea corporis (trunk) (Figure 53-7, C), tinea manus (hand), tinea cruris (groin), and tinea pedis (foot).

Clinical manifestations

The clinical signs of superficial fungal infection vary depending on the physical location and the host’s response to the invading organism. Often fungal infections are manifested as erythematous macules or plaques with peripheral scaling and some central clearing. Vesicular lesions often accompany the dry scaling on the feet. Because of the variability of signs and symptoms, superficial dermatophytosis must be considered when evaluating even a weeping, crusted area more suggestive of eczema or impetigo. Dermatophyte infection of the nails, or onychomycosis, is usually seen as a white or yellow opaque discoloration that often progresses to a thickened, crumbed, or deformed nail (Figure 53-8).

Treatment

Topical management of localized superficial dermatophyte infections is very effective. Among the topical antifungal preparations available in cream and solution form are miconazole nitrate, clotrimazole, econazole nitrate, ciclopirox olamine, and terbinafine. A 4-week course of twice-daily applications will usually clear the symptoms. For more extensive infections involving the hair, nails, or resistant organisms, systemic therapy (e.g., griseofulvin or intraconazole and terbinafine) is required. Treatment duration ranges from 3 or 4 weeks (tinea corporis) to 12 months (onychomycosis).

Yeast Infections

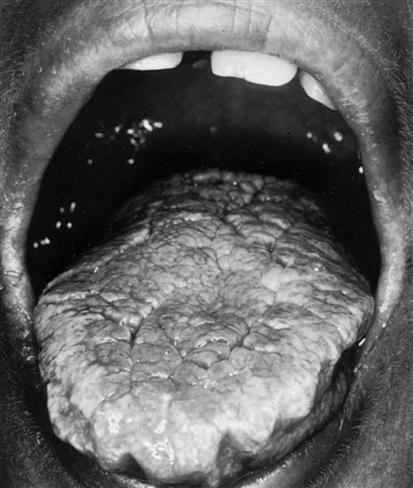

The yeast Candida albicans is another common source of superficial infection (Figure 53-9). It is manifested in newborns as the white lesions of thrush, in infants and bedridden patients as intertrigo, and in immunoimpaired individuals as the systemic disorder mucocutaneous candidiasis. Mucocutaneous candidiasis may actually be the presenting sign in an individual with a previously undiagnosed immunodeficiency disorder.

Localized yeast infections such as oral candidiasis (thrush) may be managed with nystatin mouth rinse or clotrimazole troches (throat lozenges). The topical antifungal medications mentioned earlier may also be used in the management of localized yeast infections. Widespread or systemic infections respond well to oral ketoconazole or fluconazole (Diflucan).

Bacterial Infections

Impetigo

Etiology and clinical manifestations

Impetigo is an acute, contagious skin disease characterized by the formation of vesicles, pustules, and yellowish crusts (Figure 53-10). The most common cause of infection of the skin, impetigo is caused by staphylococci or streptococci. Approximately 5% of the population each year sustains staphylococcus infections of a severity sufficient to require medical attention.8 Approximately 20% of adults are chronic carriers of the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, and another 60% are intermittent carriers.8 The bacterium is carried in the nasal area and may pass onto the skin and produce disease. Staphylococcal infections are a special problem for hospitalized patients, who may become infected from the infected hospital staff.

Treatment

Treatment for impetigo includes topical application of 2% mupirocin ointment (Bactroban) or 1% retapamulin (Altabax) ointment. If a large area of skin is involved or if the person is febrile, impetigo may be managed systemically with oral dicloxacillin, cephalexin, or erythromycin.

Syphilis

Etiology and clinical manifestations

A variety of sexually transmitted diseases caused by bacteria can infect the genitalia. The most serious is syphilis, which is caused by Treponema pallidum. If the person remains untreated, three stages can occur. In primary syphilis, a chancre (ulcer) generally occurs as a single lesion on the genitalia; the spirochetal microorganism that causes syphilis can be seen in a scraping of the chancre. Secondary syphilis is characterized by a disseminated rash that cannot be clearly distinguished from other rashes. Both the primary and the secondary stages of syphilis are contagious.

Treatment

Studies to detect serum antibodies against syphilis (such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratories [VDRL]) and examination of the pustules for the spirochete are required to achieve a diagnosis. Penicillin is very effective in eradicating syphilis in the primary and secondary stages, but unfortunately damage caused by tertiary syphilis to the cardiovascular and central nervous systems is permanent.

Leprosy

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease of the skin caused by the intracellular bacillus Mycobacterium leprae. Approximately 11 million people worldwide have leprosy.8 The diagnosis is made with a skin biopsy. Leprosy has a low rate of infectivity and is usually responsive to sulfone drugs such as dapsone. For chronic deformities, corrective orthopedic surgery may be required.

Inflammatory Conditions

Lupus Erythematosus

Lupus erythematosus (LE) is an inflammatory disease that has cutaneous manifestations. Systemic LE and chronic discoid LE are clinically dissimilar but basically related diseases. The two diseases differ with regard to characteristic skin lesions, subjective complaints, other organ involvement, LE cell test findings, response to treatment, and eventual prognosis. Discoid lupus presents with scaly red plaques with scarring that involve sun-exposed skin. Classically, systemic lupus presents with a butterfly-shaped erythema involving the cheeks and nose; discoid lesions may be seen as well. A comparison of the two conditions is found in Table 53-3. Figure 53-11 illustrates characteristic skin lesions of both conditions.

TABLE 53-3

COMPARISON OF CHRONIC DISCOID WITH SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

| PARAMETER | CHRONIC DISCOID LE | SYSTEMIC LE |

| Primary lesions | Red, scaly, thickened, well-circumscribed patches with enlarged follicles and elevated border | Red, mildly scaly, diffuse, puffy lesions; purpura also seen |

| Secondary lesions | Atrophy, scarring, and pigmentary changes | No scarring; mild hyperpigmentation |

| Distribution | Face, mainly in the “butterfly” area, but also on the scalp, ears, arms, and chest. May not be symmetric. | Face in “butterfly” area, arms, fingers, and legs; usually symmetric |

| Course | Very chronic with gradual progression; slow healing under therapy; no effect on life | Acute onset with fever, rash, malaise, and joint pains; most cases respond rather rapidly to steroid and supportive therapy, but prognosis for life is poor |

| Season | Aggravated by intense sun exposure or radiation therapy | Same |

| Gender incidence | Almost twice as common in females | Same |

| Systemic pathology | None obvious | Nephritis, arthritis, epilepsy, pancarditis, hepatitis, etc. |

| Laboratory findings | Biopsy characteristic in classic case LE cell test negative, as are other laboratory tests | Biopsy less useful |

From Sauer GC: Manual of skin diseases, ed 6, Philadelphia, 1991, Lippincott, p 253.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Clinical manifestations and treatment

Seborrheic dermatitis (Figure 53-12) is a papulosquamous skin disease manifested by various degrees of scaling and erythema in areas of high oil gland concentration such as the scalp, eyebrows, glabellae, eyelids, nasolabial folds, pinna and posterior sulcus of the ears, sternum, axillae, umbilicus, and anogenital area. Common manifestations of this disease are cradle cap in newborns and dandruff in adolescents and adults.

Although seborrheic dermatitis is not curable, it may be controlled with topical medication. The regular use of tar, zinc, selenium sulfide, or salicylic acid shampoos often clears the symptoms and signs of seborrheic dermatitis in the scalp; mild topical corticosteroids (e.g., 1% hydrocortisone) clear lesions on the face and ears.

Psoriasis

Etiology and clinical manifestations

Psoriasis is a common chronic skin disease characterized by papules and plaques with an overlying silvery scale. The specific cause of psoriasis is unknown, but it appears to be a multifactorial inherited condition in which minor aberrations of the immune system promote inflammation and hyperproliferation within the skin. The disease may affect, with varying degrees of severity, people of all ages. Lesions can appear on any area of the body; however, they seem to have a predilection for the knees, elbows, lower part of the back, scalp, and nails (Figure 53-13). Disease progression is unpredictable, and the patient may periodically experience spontaneous exacerbations or remission.

Treatment

No cure for psoriasis is known. Treatments, both topical and systemic, are directed at clearing and controlling the lesions. Therapies include topical corticosteroids (most commonly used), a vitamin D derivative (calcipotriene ointment [Dovonex]), ultraviolet light exposure, topical tar preparations, and combinations of ultraviolet light with topical tar or systemic psoralen. Systemic therapies with methotrexate and hydroxyurea are also effective in clearing psoriasis but carry considerable risk of toxicity. Newer, highly effective biological agents are now available for use by injection but are very expensive and also carry risks of significant side effects.

Lichen Planus

Etiology and pathogenesis

Lichen planus is a relatively common, chronic, pruritic disease involving inflammation and papular eruption of the skin and mucous membranes. Idiopathic lichen planus is of unknown cause but can be stimulated by a variety of drugs and chemicals in susceptible persons. The characteristic lesion is a shiny, white-topped, purplish, polygonal papule. Lesions appear on the wrists, ankles, and trunk (Figure 53-14). Mucous membrane lesions are white and lacy and may become bullous. Pruritus is severe, and new lesions develop as a result of scratching (Koebner phenomenon). Nails are affected in approximately 10% of people with lichen planus.9

Treatment

In the majority of people, lichen planus is a self-limiting disease. Treatment measures include discontinuation of all medications, followed by the administration of topical corticosteroids and occlusive dressings. Systemic corticosteroids may be indicated in severe cases, and antipruritic agents are helpful in reducing the pruritus.

Pityriasis Rosea

Etiology, pathogenesis, and treatment

Pityriasis rosea is a rash of unknown origin that primarily affects young adults. The incidence is highest in the spring and fall seasons. It has been speculated to be viral in origin, but to date no virus has been isolated. The characteristic lesion is a macule or papule with surrounding erythema. The lesion spreads with central clearing, much like tinea corporis. This initial lesion is a solitary lesion, called the herald patch, and is usually located on the trunk or neck. As the lesion enlarges and begins to fade away (2 to 10 days), successive crops of lesions appear on the trunk and neck.10 The extremities, face, and scalp may be involved, and mild to severe pruritus may occur. The disease is self-limiting and usually disappears within 2 to 10 weeks.10 Treatment is palliative and includes topical steroids, antihistamines, and colloid baths. Systemic corticosteroids may be indicated in severe cases. Systemic antibiotics, especially erythromycin, may also shorten the course.

Acne Vulgaris

Etiology and pathogenesis

Acne, an extremely common disease of the pilosebaceous unit, affects up to 90% of all individuals and produces unsightly lesions and sometimes permanent scarring and disfigurement11 (Figure 53-15). Etiologically, acne involves multiple factors such as sex hormones, heredity, bacterial flora of the skin, stress, mechanical occlusion, and cosmetics’ use. Acne arises when sludging of sebaceous oils and deposition of loose epithelial cells cause an obstruction of the follicular canal. Continued oil production and bacterial growth in this obstructed follicle may cause rupture of the wall or sebaceous gland and result in an inflamed lesion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree