Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

EDI BROGI

The term “cylindroma,” used interchangeably with “adenoid cystic carcinoma” (AdCC), was proposed by Billroth,1 who concluded that the tumor was composed of entwined cylinders of stroma and epithelial cells. Ewing2 mentioned AdCC of the salivary glands, and this term was applied in 1945 to tumors of the breast by Geschickter,3 referring to lesions he classified as “adenocystic basal cell carcinoma.” Three examples of mammary AdCC were cited by Foote and Stewart4 in 1946. Two decades later, Galloway et al.5 at the Mayo Clinic described the first series of mammary AdCCs and reviewed 12 others previously reported.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Incidence

AdCC can arise in many organs. It is most commonly found in major and minor salivary glands, and is one of the least frequent forms of primary mammary carcinoma. Only 22 cases of AdCC were recorded among nearly 28,000 patients with breast carcinoma included in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Registry database.6 The California Cancer Registry from 1988 to 20067 included 244 cases of mammary AdCC, representing 0.058% of all breast carcinomas in the same period. Review of data from nine registry areas in the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program for 1977 to 2006 yielded 338 women with AdCC with an incidence rate of 0.92 per one million person-years.8 The incidence rate was constant during the 30-year period.

Age, Gender, and Ethnicity

AdCC occurs in adult women throughout the age distribution of mammary carcinoma, with patient age ranging between 19 and 97 years.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 The mean or median age varies from 50 to 63 years in various studies. In a series of 61 cases treated between 1980 and 2007 at 16 centers that are part of the Rare Cancer Network Study,18 the median age at diagnosis was 59 years (range 28 to 94). In three studies, 70%,18 82.5%,8 and 96%19 of patients with AdCC were postmenopausal women. Most (82% to 87%) women with AdCC are White.7,16,18 Two studies7,18 found that 6% of women with AdCC were Black. In the study by Thompson et al.,7 5.7% of AdCC occurred in Asian/Pacific Islanders and 4.4% in Hispanic women. Isolated examples have been encountered in men20,21,22 and in adolescents17 (Fig. 25.1). Eight AdCCs constituted 1% of 759 primary carcinomas of the male breast in one series.23 Cutaneous AdCC has been reported in the periareolar region of a 35-year-old man.24 No specific association with familial syndromes, including familial cylindromatosis and multiple familial trichoepitheliomas (Brooke-Spiegler syndrome), has been described.

Presenting Symptoms

AdCC presents as a palpable, discrete, firm mass in about 80% of cases.18 Pain18,25,26 or tenderness26 is described in some cases. These symptoms have not been specifically correlated with the histologic finding of perineural invasion. Pain in the affected breast was reported by 14% of patients in one series.18 Skin dimpling, ulceration, and peau d’orange have been reported in patients with superficial or large lesions. Nipple discharge is rarely a presenting symptom14 despite the fact that AdCC occurs with notable frequency centrally or in the subareolar part of the breast.8,27 Rarely, AdCC arising in the nipple can be associated with Paget disease (Fig. 25.2). The most frequent sites of AdCC are the upper outer quadrant of the breast8 and the retroareolar region.8,27,28

Most patients report that their tumor was detected shortly before seeking medical attention, but intervals of 9,14,27 10,29,30 and 159 years have been described. The median duration in one series was 24 months, and six tumors were present for a year or more before diagnosis.14

The left and right breasts are equally affected,8 but there is no predilection for AdCC to develop bilaterally.8 Most tumors are unifocal, and only rare tumors consist of two18,31 or more distinct foci.18 In patients with AdCC, the frequency of subsequent carcinoma in either breast or of a solid malignant tumor at a nonmammary site is not greater than expected in the general population.8

Radiology

Mammography of clinically palpable tumors reveals a welldefined lobulated mass or an ill-defined lesion.27,32,33 A mammographic spiculated mass can also be observed.26 Only 18% of cases in the series by Khanfir et al.18 were detected by mammography. The mammograms of 8 of the 10 cases studied by Glazebrook et al.33 were abnormal. The AdCC

appeared as an irregular or lobular mass with microlobulated or indistinct margins in four of eight (50%) cases, a subtle architectural distortion in two of eight (12.5%), and as an asymmetric density in another two of eight (12.5%) cases. Two of the 10 (12.5%) AdCCs were mammographically undetected. None of the tumors had calcifications, a rare finding in AdCC. In some instances, the mammogram was reportedly negative.14,27 The sonographic appearance is that of a heterogeneous or hypoechoic mass.26,33 One tumor presented as an 8-mm hypoechoic nodule suggestive of an intramammary lymph node.34 Eight of nine tumors studied sonographically by Glazebrook et al.33 appeared as irregularly shaped hypoechoic or heterogeneous masses, oriented parallel to the skin, with no echogenic halo or posterior shadowing. Doppler sonography detected only minimal flow signal around and within the tumor. In the same study, a palpable tumor was not detected by either mammographic or sonographic examination.

appeared as an irregular or lobular mass with microlobulated or indistinct margins in four of eight (50%) cases, a subtle architectural distortion in two of eight (12.5%), and as an asymmetric density in another two of eight (12.5%) cases. Two of the 10 (12.5%) AdCCs were mammographically undetected. None of the tumors had calcifications, a rare finding in AdCC. In some instances, the mammogram was reportedly negative.14,27 The sonographic appearance is that of a heterogeneous or hypoechoic mass.26,33 One tumor presented as an 8-mm hypoechoic nodule suggestive of an intramammary lymph node.34 Eight of nine tumors studied sonographically by Glazebrook et al.33 appeared as irregularly shaped hypoechoic or heterogeneous masses, oriented parallel to the skin, with no echogenic halo or posterior shadowing. Doppler sonography detected only minimal flow signal around and within the tumor. In the same study, a palpable tumor was not detected by either mammographic or sonographic examination.

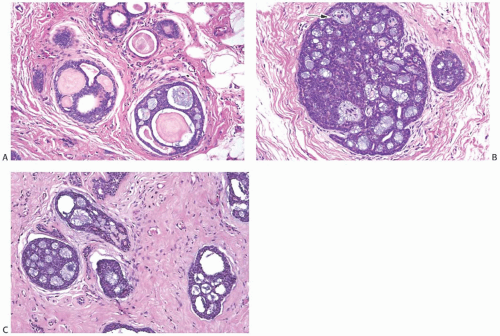

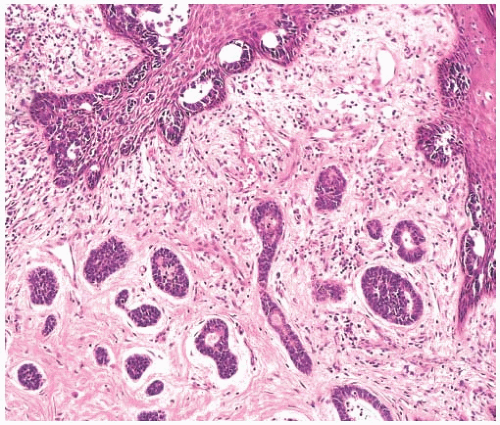

FIG. 25.1. Adenoid cystic carcinoma, child. This tumor arose in the breast of a 13-year-old boy. Juvenile breast ducts are visible in the upper left corner. |

FIG. 25.2. Paget disease and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Carcinoma glands are apparent in the epidermis overlying AdCC, which was confined to the nipple. |

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful for defining the extent of the AdCC, especially in a dense breast.33 An unusual pattern of rapid but somewhat zonal enhancement from the tumor periphery to the center has been described on T1-weighted images.35 The lesions are irregular or lobulated, with rapid and heterogeneous enhancement after injection of gadolinium and have persistent or plateau kinetic.33 T2-weighted images showed isointensity with the adjacent breast parenchyma or extensive high T2-weighted signal.

GROSS PATHOLOGY

The reported gross size of the tumors ranges from 2 mm to 25 cm.9,14,15 Most lesions measure between 1 and 3 cm. Tumors with low-grade histologic features tend to be smaller (0.5 to 2.8 cm; mean, 1.6 cm) than high-grade tumors (1.5 to 8.0 cm; mean, 3.5 cm).

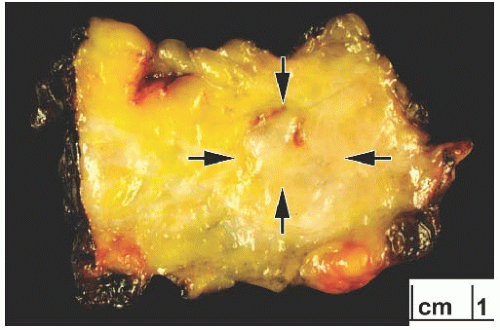

Most AdCCs are circumscribed or nodular grossly, despite a microscopically invasive growth pattern. Small cystic areas are not unusual, especially in lesions smaller than 5 cm. Larger tumors may have areas of gross cystic degeneration5,9,14 (Fig. 25.3). The lesions have been variously described as gray, pale yellow, tan, and pink (Fig. 25.4).

MICROSCOPIC PATHOLOGY

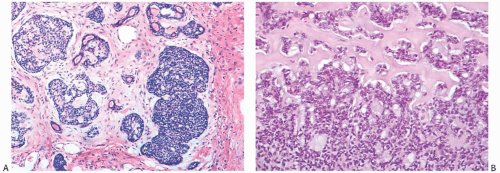

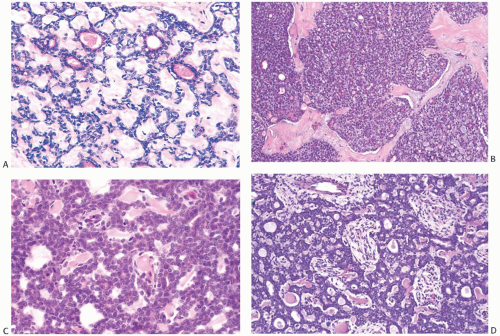

AdCC consists of a mixture of proliferating glands (adenoid component) and basaloid/myoepithelial cells producing abundant basement membrane material (“pseudoglandular” or cylindromatous component) (Fig. 25.5). These components are rarely distributed homogeneously in a given tumor (Fig. 25.6). Some areas consist predominantly of the glandular or adenoid structures, creating a close resemblance to cribriform carcinoma, either in situ or invasive (Fig. 25.5).36 Abundant basement membrane material in other parts of the tumor produces a cylindromatous pattern that, when extreme, may be mistaken for scirrhous carcinoma (Fig. 25.7).

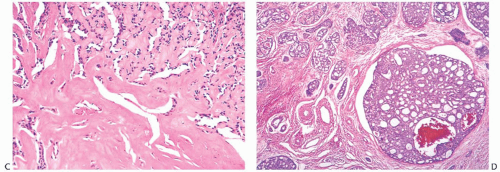

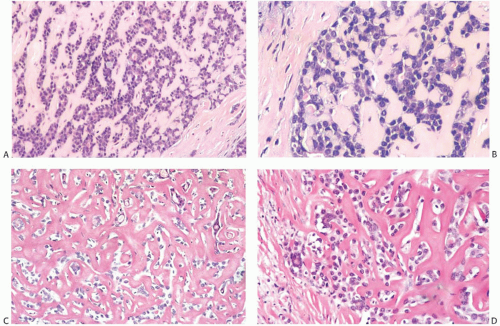

Despite a fairly circumscribed and nodular gross appearance, many AdCCs have an invasive growth pattern microscopically, in which the tumor infiltrates the surrounding breast parenchyma beyond a grossly apparent central nodule14 (Fig. 25.8). Microcystic areas formed by the coalescent spaces in dilated glands are seen in about 25% of tumors. When they are sufficiently large, these spaces can be appreciated grossly as well as microscopically (Figs. 25.8 and 25.9). Areas of nearly confluent solid growth as well as typical adenoid cystic components may be present in a single tumor (Fig. 25.10). Prominent basaloid features are seen in some instances, a pattern that is referred to as the solid variant of AdCC with basaloid features37 (Figs. 25.11, 25.12 to 25.13). Slodkowska et al.21 reported that 9/41 (22%) AdCCs in their series had basaloid morphology. Ro et al.38 suggested that AdCC be stratified into three grades on the basis of the proportion of

solid growth within the lesion: grade I, no solid elements; grade II, less than 30% solid growth; and grade III, solid areas composing more than 30% of the tumor. In high-grade lesions, tumor cells are poorly differentiated and have sparse cytoplasm, relatively large, hyperchromatic nuclei, and frequent mitoses (Figs. 25.11, 25.12, 25.13, to 25.14). High-grade AdCCs do not seem to differ from low-grade AdCCs in regard to patient age, laterality, duration before treatment, hormone receptors, or in the likelihood of finding residual tumor in a mastectomy specimen.14 Ro et al.38 found that tumors with a solid component (grades II and III) tended to be larger and were more likely to have recurrences than those without a solid element (grade I). In their series, none of five patients with a grade I AdCC developed distant metastases, whereas two of six patients with grade II AdCC recurred distally; the only patient with a grade III AdCC also developed distant metastases. In the three cases with distant disease, the morphology of the metastatic carcinoma was similar to that of the primary tumor. A patient with solid AdCC in the series by Santamaria et al.27 did not have axillary nodal metastases. The grading scheme proposed by Ro et al.38 was not prognostically significant in one study.28 In a follow-up study from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Zhu et al.15 reported that “patients with grade III tumors were more likely to have lower overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates than patients with grade I or II tumors, although the differences were not statistically significant.”

solid growth within the lesion: grade I, no solid elements; grade II, less than 30% solid growth; and grade III, solid areas composing more than 30% of the tumor. In high-grade lesions, tumor cells are poorly differentiated and have sparse cytoplasm, relatively large, hyperchromatic nuclei, and frequent mitoses (Figs. 25.11, 25.12, 25.13, to 25.14). High-grade AdCCs do not seem to differ from low-grade AdCCs in regard to patient age, laterality, duration before treatment, hormone receptors, or in the likelihood of finding residual tumor in a mastectomy specimen.14 Ro et al.38 found that tumors with a solid component (grades II and III) tended to be larger and were more likely to have recurrences than those without a solid element (grade I). In their series, none of five patients with a grade I AdCC developed distant metastases, whereas two of six patients with grade II AdCC recurred distally; the only patient with a grade III AdCC also developed distant metastases. In the three cases with distant disease, the morphology of the metastatic carcinoma was similar to that of the primary tumor. A patient with solid AdCC in the series by Santamaria et al.27 did not have axillary nodal metastases. The grading scheme proposed by Ro et al.38 was not prognostically significant in one study.28 In a follow-up study from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Zhu et al.15 reported that “patients with grade III tumors were more likely to have lower overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates than patients with grade I or II tumors, although the differences were not statistically significant.”

FIG. 25.4. Adenoid cystic carcinoma, gross appearance. A subtle ill-defined white-pink area (arrows) representing an infiltrating focus of AdCC is barely visible on the cut surface of a breast excision specimen. This is consistent with the grossly inconspicuous pattern of infiltration characteristic of AdCC. Two hemorrhagic lines in the center of the tumor constitute evidence of prior needle core biopsy. |

A variety of microscopic growth patterns found in AdCC of the salivary glands39 may also be present when this type of tumor occurs in the breast.14,38,40,41 These configurations have been described as cribriform (Fig. 25.5), tubular (Fig. 25.15), reticular (trabecular) (Fig. 25.10), solid (Fig 25.10), and basaloid (Figs. 25.11, 25.12, 25.13 to 25.14). Sebaceous metaplasia is found in 14% of AdCC (Fig. 25.16), and a substantial number of the tumors have foci of squamous differentiation (Figs. 25.9 and 25.17).42 Adenomyoepitheliomatous areas with ductular structures that resemble the intercalated ducts in salivary glands and salivary gland tumors (Fig. 25.18) and syringomatous areas (Fig. 25.19) are further evidence of structural diversity.42

Rarely, adipose differentiation and myofibroblastic hyperplasia can occur in the stroma of AdCC (Fig. 25.20). Noske et al.43 described a high-grade basaloid AdCC that gave rise to a metaplastic spindle cell and glandular adenocarcinoma with melanomatous differentiation.

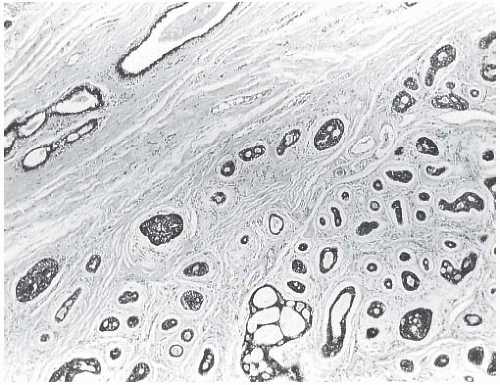

Perineural invasion (Figs. 25.14C and 25.21), a very common feature in AdCC of the oropharynx, was present in 8%18 and 15%21 of cases in two studies. It tends to be more frequent in tumors with basaloid morphology. Lymphovascular

invasion is extremely uncommon.14 Shrinkage artifacts occur relatively often in AdCC, especially in fibrotic portions of the tumor (Fig. 25.22) and should not be mistaken for lymphatic tumor emboli. The pseudovascular spaces are not lined by endothelium.

invasion is extremely uncommon.14 Shrinkage artifacts occur relatively often in AdCC, especially in fibrotic portions of the tumor (Fig. 25.22) and should not be mistaken for lymphatic tumor emboli. The pseudovascular spaces are not lined by endothelium.

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ

It is usually difficult to detect an in situ component, but in a minority of low-grade AdCCs there may be conspicuous lobular and duct involvement (Fig. 25.23). This type

of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) cannot be appreciated grossly at surgery and may be responsible for local recurrence in some cases. Intraductal AdCC with lobular extension is sometimes seen in high-grade tumors. Compared with the invasive component with cribriform morphology, the DCIS lacks the distinctive periductal cuff of cellular myxoid stroma that typically surrounds the nests of invasive AdCC. Lobules and ducts adjacent to AdCC can display adenoid cystic traits, with small cylindromatous areas (Fig. 25.24).

of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) cannot be appreciated grossly at surgery and may be responsible for local recurrence in some cases. Intraductal AdCC with lobular extension is sometimes seen in high-grade tumors. Compared with the invasive component with cribriform morphology, the DCIS lacks the distinctive periductal cuff of cellular myxoid stroma that typically surrounds the nests of invasive AdCC. Lobules and ducts adjacent to AdCC can display adenoid cystic traits, with small cylindromatous areas (Fig. 25.24).

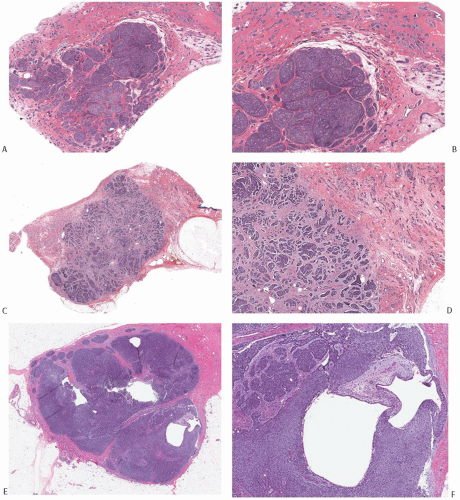

FIG. 25.8. Adenoid cystic carcinoma. A: A histologic section of an AdCC consisting of a fairly circumscribed central nodule with less conspicuous infiltration in all of the surrounding breast parenchyma. B: Magnified view of the tumor in (A) showing the nodular and solid growth in the center of the lesion and a more subtly infiltrative pattern at the tumor periphery. C: This histologic section demonstrates a circumscribed central tumor mass surrounded by small nests with an invasive pattern (upper right and left). D: Medium-power magnification of the tumor in (C). E,F: In contrast to the two carcinomas shown in (A-D), this solid and focally cystic tumor forms a discrete, circumscribed mass with no evidence of peripheral infiltration. F: Two cystic spaces in the tumor shown in (E). |

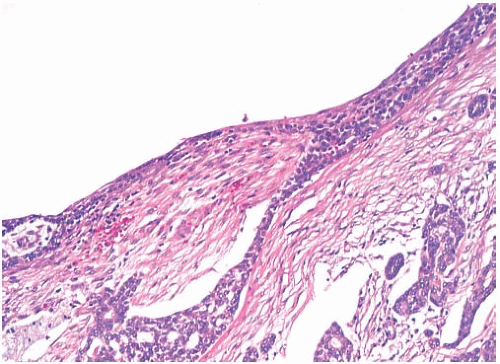

FIG. 25.9. Adenoid cystic carcinoma, cystic. The cyst cavity is lined by neoplastic epithelium with superficial squamous differentiation. |

Associated Carcinomas

Other types of carcinoma may develop in the contralateral breast,10,13,14,27 or in rare instances another type of carcinoma may be found in the same breast. One patient had separate, concurrent tubular carcinoma (Fig. 25.25) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). Another case of AdCC merged with a well-differentiated estrogen receptor (ER)-positive invasive ductal carcinoma (Fig. 25.26).

CYTOLOGY

Cytologic preparations of AdCC consist of small hyperchromatic epithelial cells with very scant cytoplasm that surround globules and cylinders of basement membrane-like material.34,44,45,46 The latter has a bright magenta color in Diff-Quik- or Giemsa-stained slides (Fig. 25.27) or a pale blue hyaline quality in Papanicolau-stained preparations. In

contrast to pleomorphic adenoma, the neoplastic cells surround the deposits of matrix material, but are not present within it. The differential diagnosis of a cytologic preparation from an AdCC includes invasive cribriform carcinoma, cribriform DCIS

contrast to pleomorphic adenoma, the neoplastic cells surround the deposits of matrix material, but are not present within it. The differential diagnosis of a cytologic preparation from an AdCC includes invasive cribriform carcinoma, cribriform DCIS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree