Chapter Forty-One. Abnormalities of uterine action and onset of labour

Introduction

Normal labour begins spontaneously at term, i.e. after 37 completed weeks and before 42 completed weeks of pregnancy (McCormick 2003). The contractions increase in length, strength and frequency, resulting in progressive descent of the fetus and dilatation of the cervical os until the fetus, placenta and membranes are expelled from the uterus and bleeding is controlled. Normal labour is also characterised by harmonious interaction between the two poles of the uterus: the upper uterine segment contracts and retracts and the lower uterine segment thins out and the cervix dilates.

Abnormalities of uterine action

Prolonged labour

The first stage of labour can be described as having latent, active and deceleration phases. During the latent phase, the uterus contracts regularly and the cervix effaces and dilates and this will determine the progress (Simkin & Ancheta 2005). The latent phase lasts until cervical dilatation is about 3–4 cm; this can take 6–8 h in a primigravida. The active phase with rapid dilatation of the cervix is about 1 cm/h in a primigravida and 1.5 cm/h in a multigravida. Defining the term ‘prolonged labour’ is problematic and related to a chosen length, mainly because of a belief that, the longer labour lasts, the more danger there is for mother and fetus. It is important to remember that although prolonged labour is common in primigravidae it occurs less often in multigravidae and may be due to obstruction of labour, where rupture of the uterus may follow careless use of oxytocic drugs in a multigravid labour.

There has been a trend to reduce the accepted length of labour in a primigravida over the last 40 years from 24 to 12 h. If the length of the latent phase of the first stage of labour in a primigravida is accepted as 6 h, resulting in a dilatation of 4 cm, and average progress of dilatation up to 10 cm in the active and deceleration phases is 1 cm/h, it is easy to see how 12 h has become the accepted norm. Labour may be prolonged in the latent, active or deceleration phases. However, NICE (2007) advocate that the length of labour for a primigravida should be on average 8 h and not last more than 18 h, whereas a multigravida labour is shorter with an average of 5 h and not lasting more than 12 h. They stipulate that all aspects of labour progress should be assessed prior to diagnosing a delay in the first stage of labour such as: cervical dilatation of less than 2 cm in 4 h for both primigravida and multigravida or slowing down of labour in multigravida; a change in the frequency, duration and strength of uterine contractions; descent and rotation of the fetal head. This is echoed by Simkin & Ancheta (2005) who state that it is important that correct diagnosis is made. They highlight that, for labour to progress, six events must occur:

1. Posterior cervix changes to the anterior position.

2. Ripening and softening of the cervix.

3. Effacement of the cervix.

4. Dilatation of the cervix.

5. Flexion, rotation and moulding of fetal head.

6. Descent and further rotation of fetus and birth.

Timing of the onset of labour

A further difficulty is how to define the onset of labour. As discussed in Chapter 36, the timing is important as it allows decisions to be made about the progress and ongoing management of labour yet it is difficult to establish with accuracy. Gibb (1988) discusses the concept of pre-labour, meaning the changes that occur in the last few weeks of pregnancy. It is often difficult to decide when the transition from the painless uterine contractions of pre-labour develops into true labour. This is reiterated by Simkin & Ancheta (2005), who argue that most slow labours do progress into normal labour patterns so it is difficult to accurately state that a labour is dysfunctional until the active phase. A slow labour before women become established is sometimes referred to as a ‘hesitant labour’.

Latent or active phase?

There is lack of agreement about whether to count the onset of labour from the onset of the latent phase or the active phase of the first stage of labour (Church & Hodgson 2004). The most frequently used marker for the commencement of labour is the onset of regular rhythmic painful uterine contractions. This is an arbitrary point in time rather than a biologically correct starting point (Enkin et al 2000). Vaginal examination of women at the time of admission demonstrates that the decision to present for admission in labour varies, depending on the advice the woman has been given on recognising the onset of labour and her anxieties and expectations.

Dangers of prolonged labour to the mother and fetus

Maternal risks

The physical effort, pain and anxiety of a prolonged labour result in dehydration, ketosis and tiredness. If this were to be allowed to continue:

• Maternal distress could occur: the temperature, pulse and blood pressure rise; dehydration, oliguria and ketosis develop; and the woman may vomit.

• If undetected cephalopelvic disproportion is present, the uterus may rupture.

• Other risks include trauma to the bladder, operative interventions and postpartum haemorrhage.

• If the membranes are ruptured, intrauterine infection is a risk (Smyth et al 2007).

• Haemorrhage is also associated with prolonged labour (Smyth et al 2007).

Fetal risks

• Intrapartum hypoxia may cause acidosis, fetal distress, neonatal asphyxia and meconium aspiration, possibly leading to perinatal death.

• Cerebral trauma may occur due to excessive pounding of the fetal head against the bony pelvis or excessive moulding.

• Prolonged rupture of the membranes may result in neonatal infection, e.g. pneumonia.

The Stillbirth, Neonatal and Post-Neonatal Mortality Report still suggests that of the intrapartum causes of fetal mortality 1.1% are due to mechanical complications (CEMACH 2007).

Inefficient uterine action

Uterine contractions are inefficient if they do not result in dilatation of the cervix. Inefficient uterine action is the most common cause of abnormal labour in primigravidae. O’Driscoll et al (1993) showed that inefficient uterine action caused delay in 65% of 9018 nulliparous women with prolonged labour. The remaining cases were caused by persistent occipitoposterior position (24%) and cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) (11%) (Malone et al 1996). There is slow progress and the length of labour is prolonged. Inefficiency may be because the contractions are too weak ( hypotonic uterine action) or because there is loss of coordination between the upper and lower uterine segments ( incoordinate uterine action).

Hypotonic uterine action

The uterine contractions are weak and short and there is slow dilatation or no dilatation of the cervix. The woman does not find the contractions too painful or distressing. The fetus remains in good condition. If hypotonic contractions occur from the commencement of labour, they are said to be primary. The cause of primary hypotonic uterine action is unknown but is more commonly seen in primigravidae. If they begin after a period of normal uterine action, they are said to be secondary and there may be abnormalities of labour such as CPD, malposition of the occiput, a malpresentation, maternal dehydration or ketosis. The commencement of epidural analgesia sometimes causes hypotonic uterine action (Church & Hodgson 2004) due to the relaxation of the pelvic floor, which interferes with the mechanisms of labour.

Incoordinate uterine action

There is loss of polarity and an increase in resting tone of the uterus. The contractions are frequent and painful and the woman feels pain between contractions. The woman feels the contraction before and after it is palpable abdominally. The cervix dilates slowly or not at all. Placental blood flow is decreased, which might lead to fetal distress. This type of uterine action is associated with malpositions of the occiput. If there is not maternal problems or fetal distress it is important to alleviate the woman’s anxiety and try mobilisation first, which might aid progress in labour prior to active management and introduction of interventions (Church & Hodgson 2004).

Active management of labour

In the 1960s, O’Driscoll introduced active management of labour for the management of labour in primigravidae (O’Driscoll et al 1986). There must be accurate diagnosis of the onset of labour with painful uterine contractions and either complete effacement of the cervix, a show or spontaneous rupture of the membranes (Henderson 1996). Amniotomy is carried out shortly after admission with augmentation of labour with Syntocinon (oxytocin) if there is inadequate progress after 1 h. Some maternity units have a policy of putting up a Syntocinon infusion immediately after amniotomy. All women are given adequate emotional support and ongoing peer review to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the protocol (Church & Hodgson 2004, Gerhardstein et al 1995).

Augmentation of labour

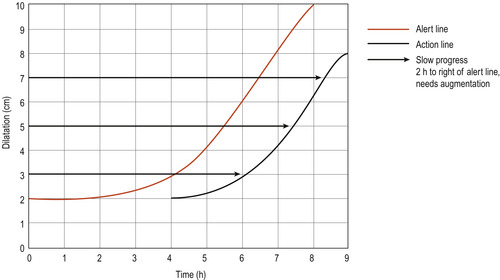

A Syntocinon infusion is used to manage prolonged labour when progress is slow but otherwise normal. This is acceleration or augmentation of labour. Once delay has been diagnosed and abnormalities of presentation or CPD ruled out, the membranes are ruptured and an intravenous infusion of Syntocinon is commenced to stimulate labour contractions. Any abnormality of fluid and electrolyte balance is corrected and both mother and fetus are monitored carefully. Adequate pain relief should be provided. Findings regarding the progress of labour should be recorded graphically on a partogram (Fig. 41.1) so that deviations from normal can be immediately recognised. There should be good psychological support of the woman. This should include explanation of what is happening and reassurance that everything is going as planned.

|

| Figure 41.1 Normogram/partogram of cervimetric progress commencing at 2 cm dilatation. ‘Alert’ line outlines normal progress. ‘Action’ line indicates when augmentation should be instituted. (After Studd 1973.) |

Amniotomy

The benefits of intact membranes throughout labour include reduced risk of intrauterine infection (Smyth et al 2007) and of fetal hypoxia because of less placental compression and less reduction of size of the placental site. Amniotomy is the artificial rupture of the fetal membranes that results in drainage of liquor (Shiers 2003). This procedure has been practiced for several decades and is usually performed to accelerate labour. Amniotomy may also be done to examine the amniotic fluid for the presence of meconium.

In a systematic review, Smyth et al (2007) studied the effects of amniotomy on the rate of caesarean sections and other indicators of maternal and neonatal morbidity. They concluded that amniotomy in spontaneous labour should not be routine practice. There was no difference in length of first stage of labour, maternal satisfaction or Apgar scores less than 7 at 5 min. The review showed an upward trend in the number of caesarean sections performed. The reviewers suggest that the findings from the paper should be discussed with women prior to amniotomy in labour being conducted. In similar fashion, Church & Hodgson (2004) believe there should be a clear indication of the need for amniotomy before it is carried out.

Oxytocic infusion

Church & Hodgson (2004) report that the use of oxytocin for labour varies, whereas O’Driscoll et al (1993) state the rates are as high as 45%. As described above, the benefits are correction of inefficient uterine action, a shorter labour, a reduced rate of caesarean section with a corresponding increase in vaginal delivery. Byrne et al (1993) found no evidence that an oxytocic infusion generated excessive intrauterine pressures. However, women experience more painful contractions and are restricted in their ability to move about.

The division of the first stage of labour into latent, active and deceleration phases must be considered as being important to the use and efficacy of oxytocin. Olah et al (1993) found that cervical muscle fibres constrict in response to oxytocin in the latent phase, leading to a poor response; they also described high intrauterine pressures and the possibility of fetal distress, although O’Driscoll et al (1993) found no evidence of this.

Expectations of childbirth have developed and the medicalisation of a normal physiological process was criticised in the 1980s (Walkinshaw 1994). There is now much variation in practice between units and, until recently, maternal satisfaction with delivery has not been considered in research protocols. Enkin et al (2000) summarised the evidence and did not think there was any benefit to women and their babies of liberal use of oxytocic infusions. They concluded that, although the use of an oxytocic infusion had its place in the management of women enduring a prolonged labour, other measures such as ambulation and allowing intake of appropriate nutrition should be considered before labelling a labour as abnormal and using medical intervention (Church & Hodgson 2004).

Prolonged second stage of labour

A discussion on the acceptable length of the second stage of labour is presented in Chapter 39. Delayed progress may be due to:

• Inefficient uterine action (primary powers).

• Inefficient maternal effort (secondary powers).

• A full bladder or rectum, a rigid perineum.

• A contracted pelvic outlet.

• A large baby.

• A fetal abnormality such as hydrocephaly or abdominal enlargement.

• Persistent occipitoposterior position.

• Deep transverse arrest of the head.

• Malpresentation.

Management

The condition of mother and fetus should be carefully assessed and as long as progress is being made, although slowly, more time may be given. Adopting an upright position, kneeling, standing or squatting may enlarge the pelvic outlet (Simkin & Ancheta 2005) and direct the presenting part against the posterior vaginal wall, utilising Ferguson’s reflex with the release of oxytocin. If the maternal or fetal condition becomes worrying or there is no obvious progress, an assisted vaginal delivery or, more rarely, a caesarean section may be needed.

Over-efficient uterine action

Precipitate labour

A precipitate labour occurs when the uterine contractions occur frequently and are intense. There is rapid completion of the first and second stages of labour and delivery normally occurs within an hour. This condition is much more common in the multigravid woman and is usually caused by lack of resistance of the maternal soft tissues. There may have been minimal pain in the first stage of labour and the woman becomes aware of imminent delivery when the head is about to be born.

Dangers of precipitate labour

The woman may have lacerations to the cervix and perineum. Postpartum haemorrhage may follow. The baby may be hypoxic and may sustain intracranial injuries because of rapid descent through the birth canal. If the birth takes place in an inappropriate place, the baby may be injured. Any labouring woman with a history of a previous precipitate delivery should not be left alone and watched very closely when in labour.

Tonic contraction of the uterus

This rare event, where the tone of the uterus is continuously high and there is no relaxation of the uterine muscle, is accompanied by intense pain. The fetus becomes distressed as the placental circulation is grossly restricted. Intrauterine death may occur. Causes may be obstructed labour or misuse of oxytocic drugs such as Syntocinon and prostaglandins. This is an emergency and immediate treatment may save the baby’s life and prevent uterine rupture:

• If an oxytocic infusion is in progress, discontinue (NICE 2008).

• Turn the mother onto her left side to enhance uteroplacental blood flow.

• Inform the obstetrician, who will review the woman with regards to caesarean section.

Administration of facial oxygen was common practice; however, there is no evidence to support either prophylaxis or short-term use of oxygen for fetal compromise (Fawole & Hofmeyr 2003, NICE 2008).

Cervical dystocia

Cervical dystocia, where the cervix dilates slowly if at all, may be congenital or acquired. Congenital problems may be fibrosis, stenosis or poor cervical development. Acquired cervical dystocia may be due to fibrosis and scarring of the cervix following surgery, cautery or irradiation. In the past when there was failure to recognise the condition, prolonged pressure would result in ischaemia and there would be annular detachment of the cervix.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree