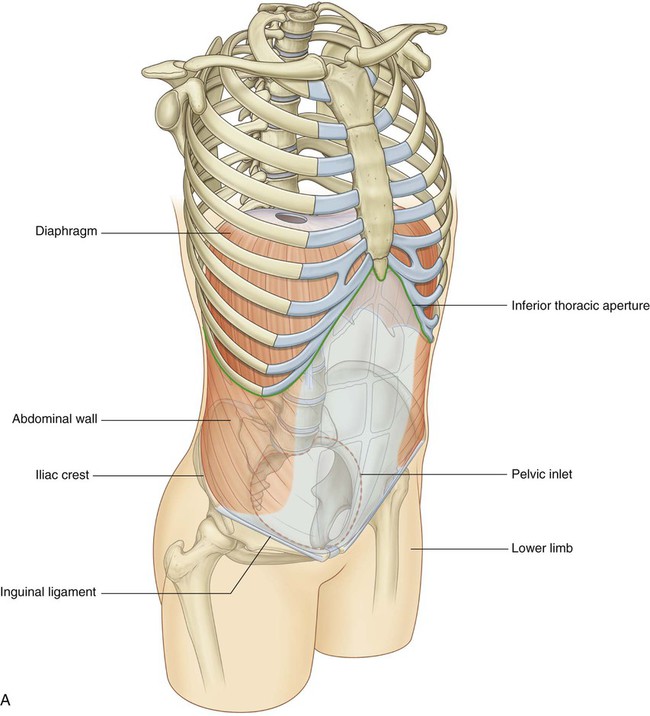

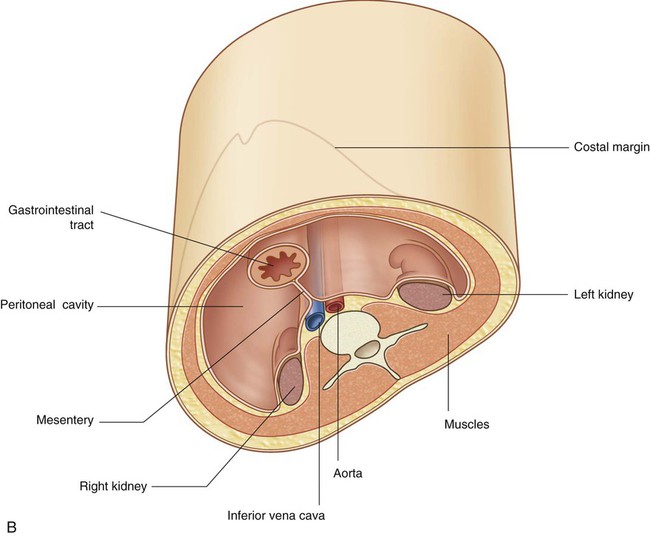

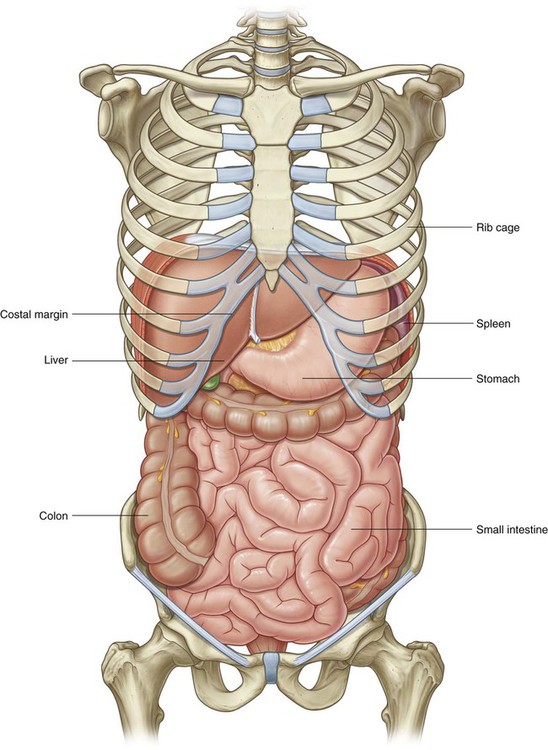

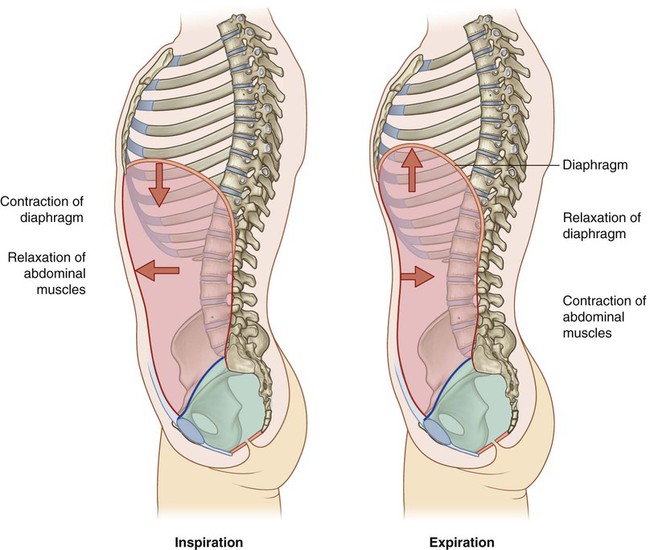

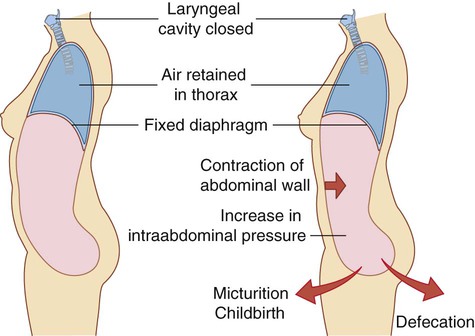

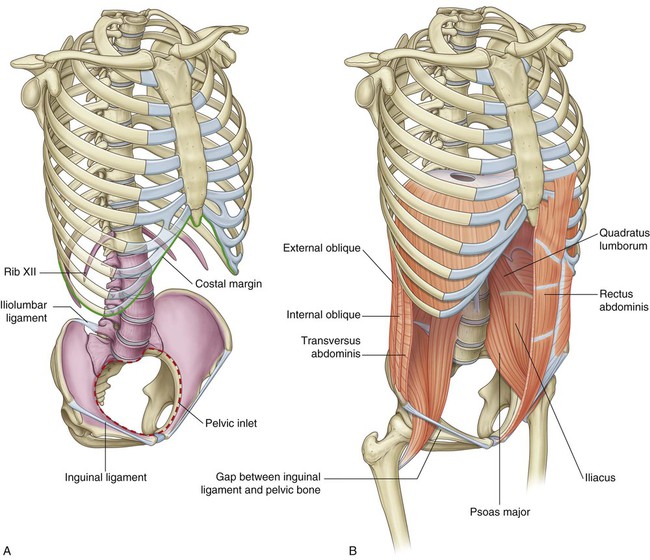

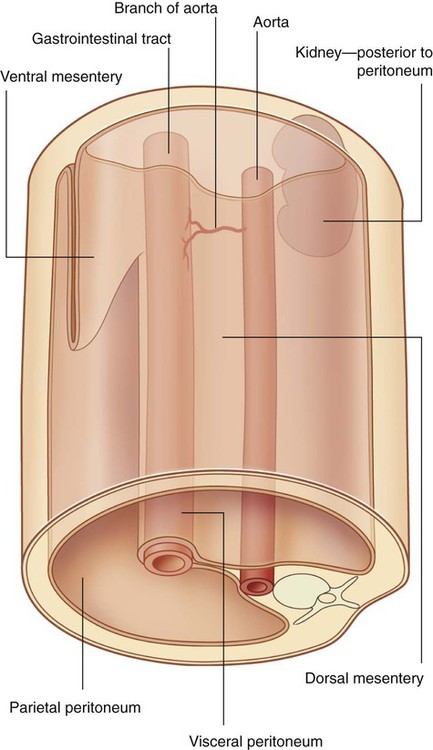

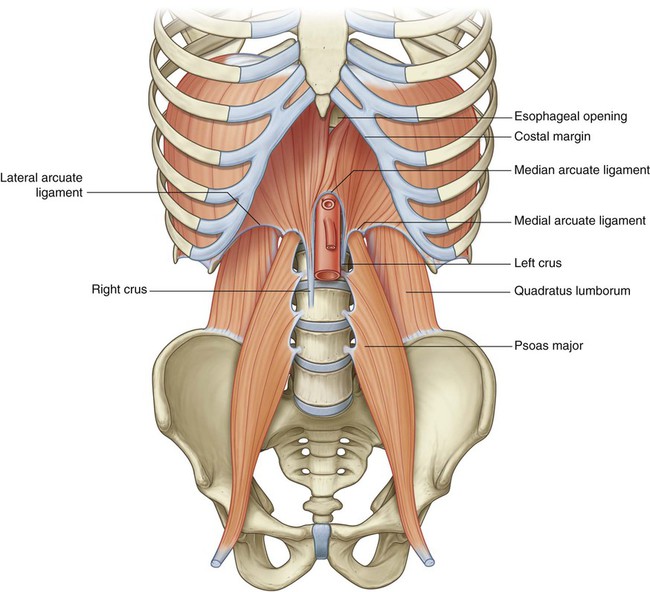

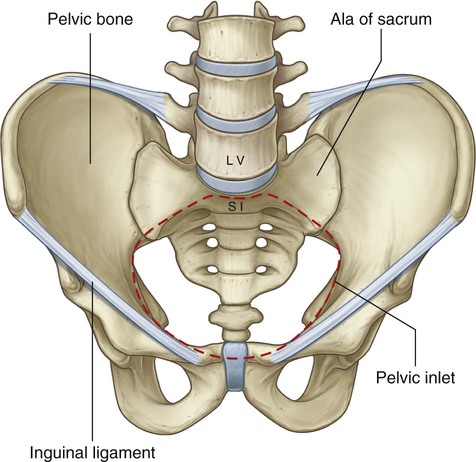

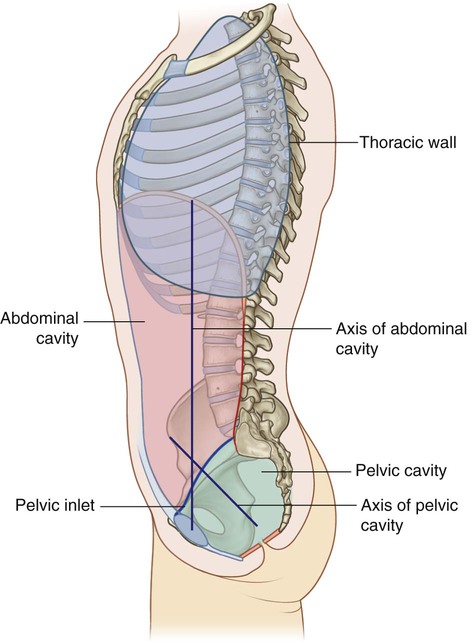

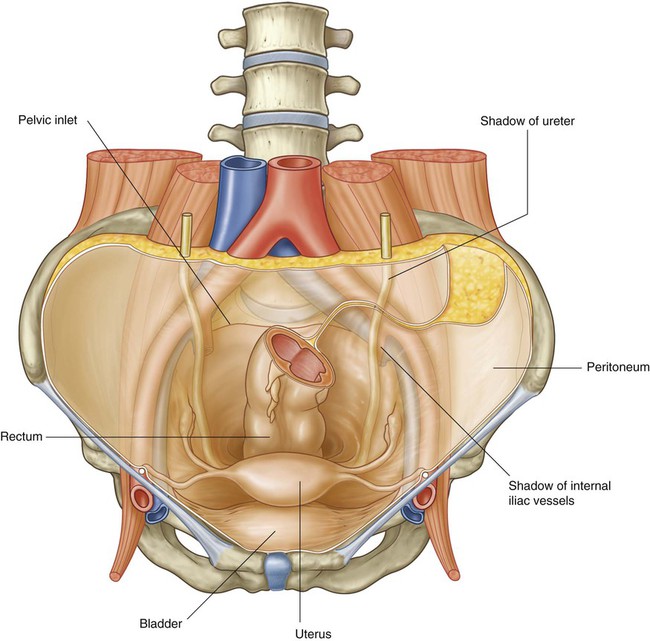

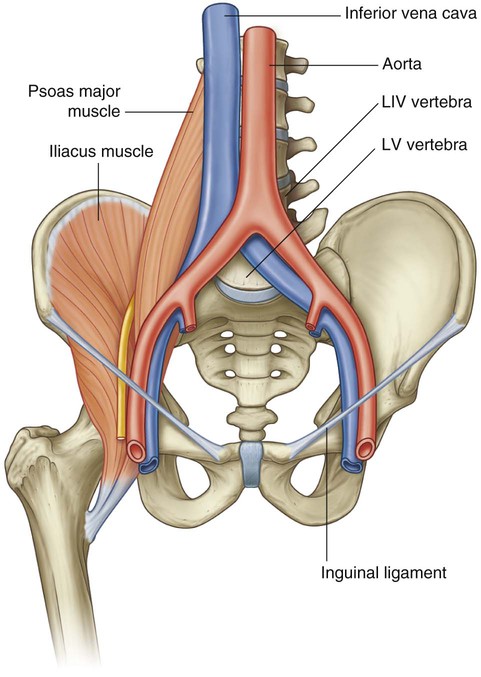

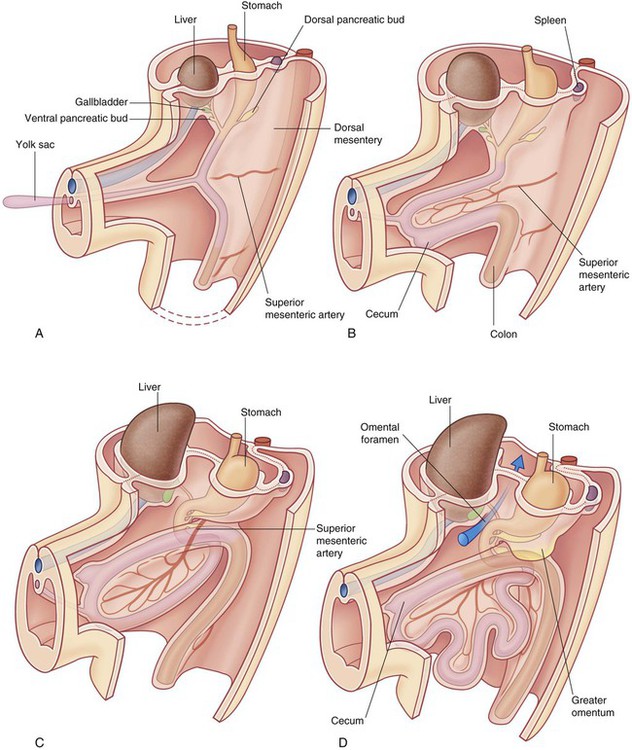

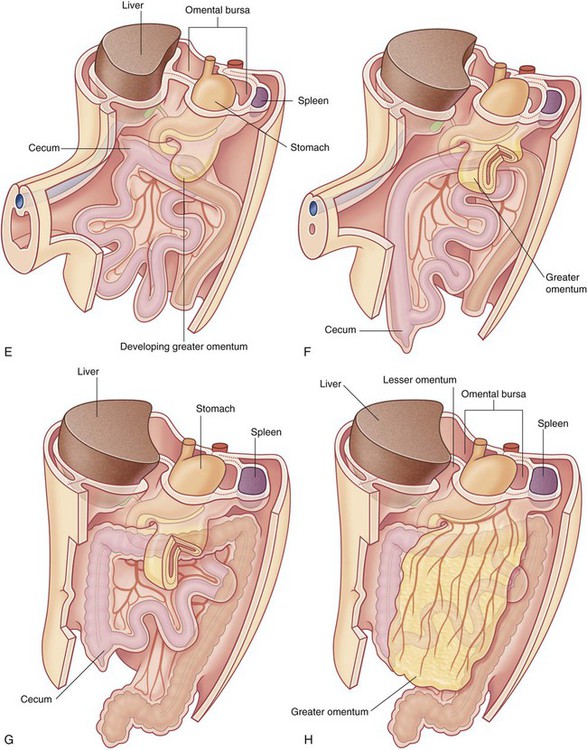

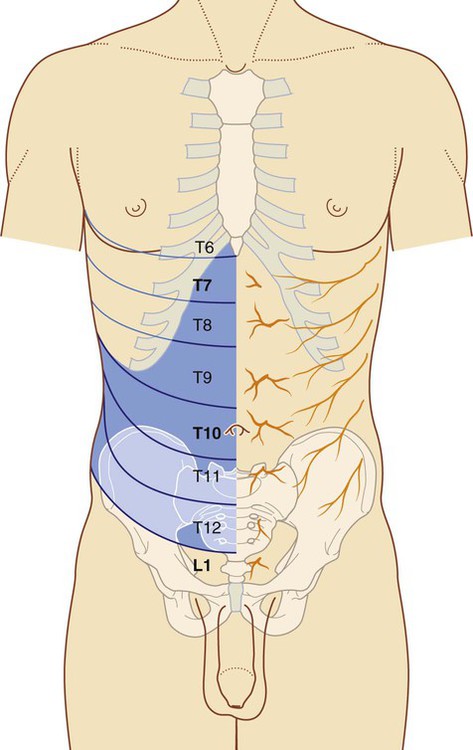

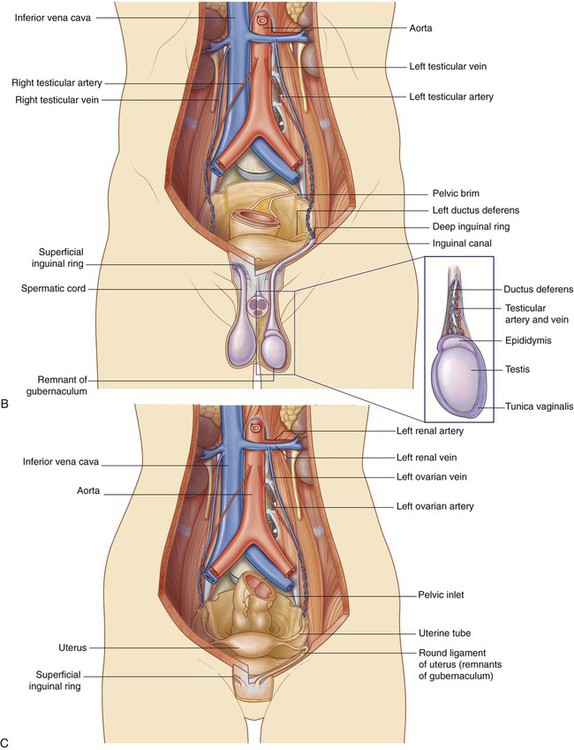

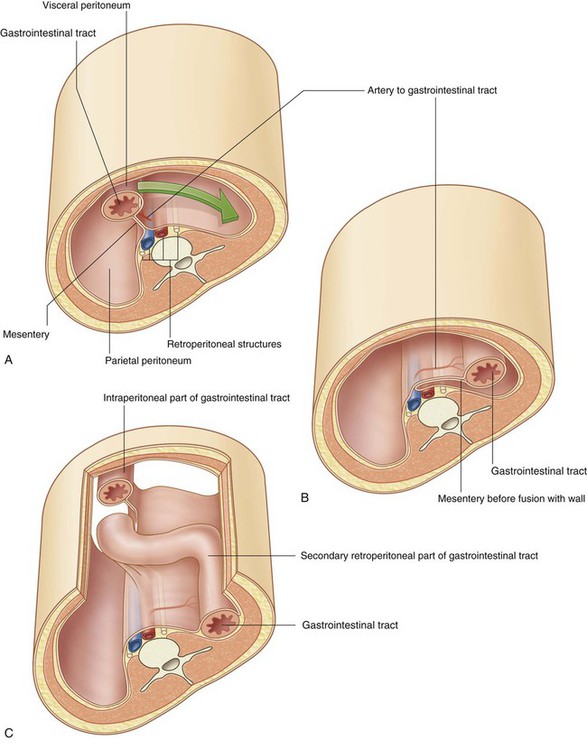

The abdomen is a roughly cylindrical chamber extending from the inferior margin of the thorax to the superior margin of the pelvis and the lower limb (Fig. 4.1A). Abdominal viscera are either suspended in the peritoneal cavity by mesenteries or positioned between the cavity and the musculoskeletal wall (Fig. 4.1B). The abdomen houses major elements of the gastrointestinal system (Fig. 4.2), the spleen, and parts of the urinary system. One of the most important roles of the abdominal wall is to assist in breathing: Contraction of abdominal wall muscles can dramatically increase intraabdominal pressure when the diaphragm is in a fixed position (Fig. 4.4). Air is retained in the lungs by closing valves in the larynx in the neck. Increased intra-abdominal pressure assists in voiding the contents of the bladder and rectum and in giving birth. The abdominal wall consists partly of bone but mainly of muscle (Fig. 4.5). The skeletal elements of the wall (Fig. 4.5A) are: Muscles make up the rest of the abdominal wall (Fig. 4.5B): The general organization of the abdominal cavity is one in which a central gut tube (gastrointestinal system) is suspended from the posterior abdominal wall and partly from the anterior abdominal wall by thin sheets of tissue (mesenteries; Fig. 4.6): Abdominal viscera are either intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal: During development, some organs, such as parts of the small and large intestines, are suspended initially in the abdominal cavity by a mesentery, and later become retroperitoneal secondarily by fusing with the abdominal wall (Fig. 4.7). The superior aperture of the abdomen is the inferior thoracic aperture, which is closed by the diaphragm (see pp. 126-127). The margin of the inferior thoracic aperture consists of vertebra TXII, rib XII, the distal end of rib XI, the costal margin, and the xiphoid process of the sternum. The musculotendinous diaphragm separates the abdomen from the thorax. The diaphragm attaches to the margin of the inferior thoracic aperture, but the attachment is complex posteriorly and extends into the lumbar area of the vertebral column (Fig. 4.8). On each side, a muscular extension (crus) firmly anchors the diaphragm to the anterolateral surface of the vertebral column as far down as vertebra LIII on the right and vertebra LII on the left. The circular margin of the pelvic inlet is formed entirely by bone: Because of the way in which the sacrum and attached pelvic bones are angled posteriorly on the vertebral column, the pelvic cavity is not oriented in the same vertical plane as the abdominal cavity. Instead, the pelvic cavity projects posteriorly, and the inlet opens anteriorly and somewhat superiorly (Fig. 4.10). The abdomen is separated from the thorax by the diaphragm. Structures pass between the two regions through or posterior to the diaphragm (see Fig. 4.8). The abdomen communicates directly with the thigh through an aperture formed anteriorly between the inferior margin of the abdominal wall (marked by the inguinal ligament) and the pelvic bone (Fig. 4.12). Structures that pass through this aperture are: A basic knowledge of the development of the gastrointestinal tract is needed to understand the arrangement of viscera and mesenteries in the abdomen (Fig. 4.13). Superiorly, the dorsal and ventral mesenteries are anchored to the diaphragm. The anterior rami of thoracic spinal nerves T7 to T12 follow the inferior slope of the lateral parts of the ribs and cross the costal margin to enter the abdominal wall (Fig. 4.14). Intercostal nerves T7 to T11 supply skin and muscle of the abdominal wall, as does the subcostal nerve T12. In addition, T5 and T6 supply upper parts of the external oblique muscle of the abdominal wall; T6 also supplies cutaneous innervation to skin over the xiphoid. Dermatomes of the anterior abdominal wall are indicated in Figure 4.14. In the midline, skin over the infrasternal angle is T6 and that around the umbilicus is T10. L1 innervates skin in the inguinal and suprapubic regions. During development, the gonads in both sexes descend from their sites of origin on the posterior abdominal wall into the pelvic cavity in women and the developing scrotum in men (Fig. 4.15). In both men and women, the groin (inguinal region) is a weak area in the abdominal wall (Fig. 4.15) and is the site of inguinal hernias.

Abdomen

Conceptual overview

General description

major elements of the gastrointestinal system—the caudal end of the esophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder;

major elements of the gastrointestinal system—the caudal end of the esophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder;

components of the urinary system—kidneys and ureters;

components of the urinary system—kidneys and ureters;

Functions

Houses and protects major viscera

Breathing

It relaxes during inspiration to accommodate expansion of the thoracic cavity and the inferior displacement of abdominal viscera during contraction of the diaphragm (Fig. 4.3).

It relaxes during inspiration to accommodate expansion of the thoracic cavity and the inferior displacement of abdominal viscera during contraction of the diaphragm (Fig. 4.3).

During expiration, it contracts to assist in elevating the domes of the diaphragm, thus reducing thoracic volume.

During expiration, it contracts to assist in elevating the domes of the diaphragm, thus reducing thoracic volume.

Changes in intraabdominal pressure

Component parts

Wall

the five lumbar vertebrae and their intervening intervertebral discs,

the five lumbar vertebrae and their intervening intervertebral discs,

the superior expanded parts of the pelvic bones, and

the superior expanded parts of the pelvic bones, and

bony components of the inferior thoracic wall, including the costal margin, rib XII, the end of rib XI, and the xiphoid process.

bony components of the inferior thoracic wall, including the costal margin, rib XII, the end of rib XI, and the xiphoid process.

Lateral to the vertebral column, the quadratus lumborum, psoas major, and iliacus muscles reinforce the posterior aspect of the wall. The distal ends of the psoas major and iliacus muscles pass into the thigh and are major flexors of the hip joint.

Lateral to the vertebral column, the quadratus lumborum, psoas major, and iliacus muscles reinforce the posterior aspect of the wall. The distal ends of the psoas major and iliacus muscles pass into the thigh and are major flexors of the hip joint.

Lateral parts of the abdominal wall are predominantly formed by three layers of muscles, which are similar in orientation to the intercostal muscles of the thorax—transversus abdominis, internal oblique, and external oblique.

Lateral parts of the abdominal wall are predominantly formed by three layers of muscles, which are similar in orientation to the intercostal muscles of the thorax—transversus abdominis, internal oblique, and external oblique.

Anteriorly, a segmented muscle (the rectus abdominis) on each side spans the distance between the inferior thoracic wall and the pelvis.

Anteriorly, a segmented muscle (the rectus abdominis) on each side spans the distance between the inferior thoracic wall and the pelvis.

Abdominal cavity

a ventral (anterior) mesentery for proximal regions of the gut tube;

a ventral (anterior) mesentery for proximal regions of the gut tube;

a dorsal (posterior) mesentery along the entire length of the system.

a dorsal (posterior) mesentery along the entire length of the system.

Intraperitoneal structures, such as elements of the gastrointestinal system, are suspended from the abdominal wall by mesenteries;

Intraperitoneal structures, such as elements of the gastrointestinal system, are suspended from the abdominal wall by mesenteries;

Structures that are not suspended in the abdominal cavity by a mesentery and that lie between the parietal peritoneum and abdominal wall are retroperitoneal in position.

Structures that are not suspended in the abdominal cavity by a mesentery and that lie between the parietal peritoneum and abdominal wall are retroperitoneal in position.

Inferior thoracic aperture

Diaphragm

Medial and lateral arcuate ligaments cross muscles of the posterior abdominal wall and attach to vertebrae, the transverse processes of vertebra LI and rib XII, respectively.

Medial and lateral arcuate ligaments cross muscles of the posterior abdominal wall and attach to vertebrae, the transverse processes of vertebra LI and rib XII, respectively.

A median arcuate ligament crosses the aorta and is continuous with the crus on each side.

A median arcuate ligament crosses the aorta and is continuous with the crus on each side.

Pelvic inlet

anteriorly by the pubic symphysis, and

anteriorly by the pubic symphysis, and

laterally, on each side, by a distinct bony rim on the pelvic bone (Fig. 4.9).

laterally, on each side, by a distinct bony rim on the pelvic bone (Fig. 4.9).

Relationship to other regions

Thorax

Lower limb

the major artery and vein of the lower limb;

the major artery and vein of the lower limb;

the femoral nerve, which innervates the quadriceps femoris muscle, which extends the knee;

the femoral nerve, which innervates the quadriceps femoris muscle, which extends the knee;

the distal ends of psoas major and iliacus muscles, which flex the thigh at the hip joint.

the distal ends of psoas major and iliacus muscles, which flex the thigh at the hip joint.

Key features

Arrangement of abdominal viscera in the adult

Skin and muscles of the anterior and lateral abdominal wall and thoracic intercostal nerves

The groin is a weak area in the anterior abdominal wall

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Abdomen