Impact

Six intestinal nematodes commonly infect humans: Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm), Trichuris trichiura (whipworm), Ascaris lumbricoides (large roundworm), Necator america-nus and Ancylostoma duodenale (hookworms), and Strongyloides stercoralis. Together, they infect more than 25% of the human race, producing embarrassment, discomfort, malnutrition, anemia, and occasionally death. Other closely related nematodes of animals that may occasionally infect humans are also listed in Table 54–1, but are not discussed here.

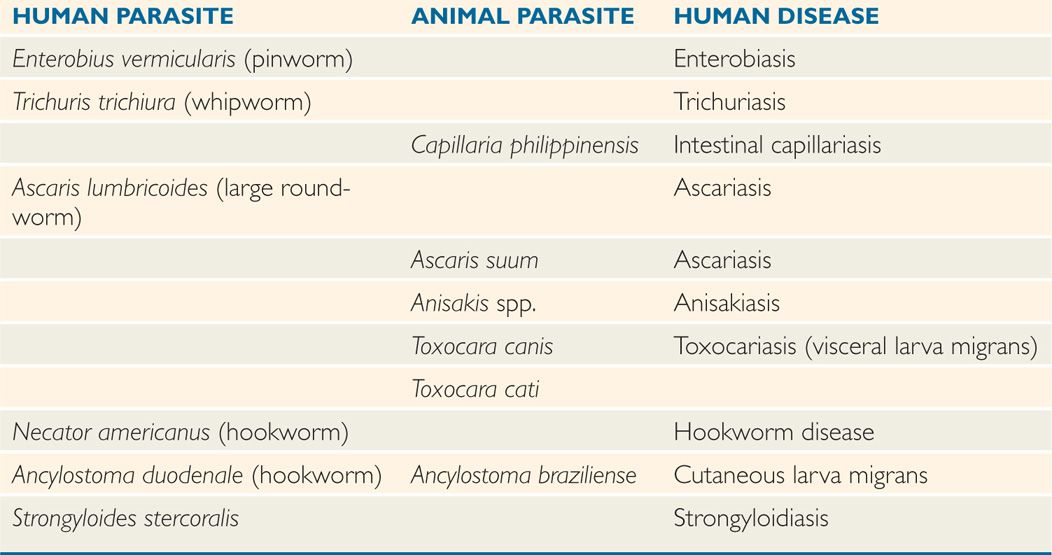

TABLE 54–1 Intestinal Nematodes

Morphology

Morphology

All intestinal nematodes have cylindrical, tapered bodies covered with a tough, acellular cuticle. Sandwiched between this integument and the body cavity are layers of muscle, longitudinal nerve trunks, and an excretory system. A tubular alimentary tract consisting of a mouth, esophagus, midgut, and anus runs from the anterior to the posterior extremity. Highly developed reproductive organs fill the remainder of the body cavity. The sexes are separate; the male worm is generally smaller than its mate.

Life Cycles

Life Cycles

Helminth life cycles may seem arcane, but they reveal how the pathogen will be transmitted to a new host. Therefore, physicians and public health experts who aim to develop strategies for prevention and control must understand life cycle fundamentals. The life cycles of the six main human intestinal nematodes are summarized in Table 54–2.

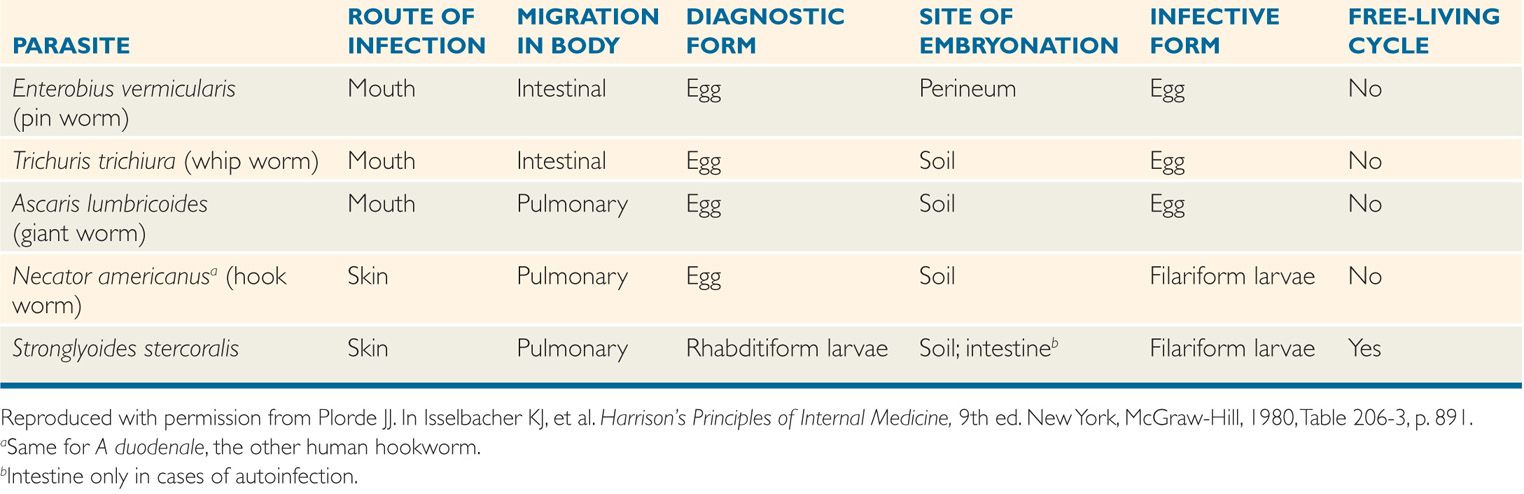

TABLE 54–2 Life Cycles of Intestinal Nematodes

The female worm is extremely prolific, and can produce thousands of offspring every day, generally in the form of eggs. In many cases, eggs are fertilized and then carried from the adult to the environment in human feces. Typically, the eggs must incubate or “embryo-nate” outside of the human host before they become infectious to another person; during this time, the embryo repeatedly segments, eventually developing into an adolescent form known as a larva. The egg may then be ingested with contaminated food. In some species, the egg hatches outside of the host, releasing a larva capable of penetrating the skin of a person who comes in direct physical contact with it. Obviously, intestinal nematodes are principally found in areas where human feces are deposited indiscriminately or used for fertilizer.

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

The adults of each of the six nematodes listed previously can survive for months or years within the lumen of the human gut. The severity of illness produced by each depends on the level of adaptation to the host it has achieved. Some species have a simple life cycle that can be completed without serious consequences to the host. Less well-adapted parasites, on the other hand, have more complex cycles, often requiring tissue invasion and/or production of enormous numbers of offspring to ensure their continued survival and dissemination. Within a given species, disease severity is related directly to the number of adult worms harbored by the host. The greater the worm load or worm burden, the more serious the consequences. Because most nematodes do not multiply within the human, small worm loads may remain asymptomatic and undetected throughout the life span of the parasite. Repeated infections, however, progressively increase the worm burden and at some point may cause symptomatic disease. Although humans can mount an immune response that may eventually contribute to the expulsion of worms, it is slow to develop and incomplete. It is therefore the frequency and intensity of reinfection more than the host’s immune response that determine the worm burden. This burden is seldom uniform within affected populations, but rather “aggregated” within subgroups related to their hygienic practices or perhaps undefined immunologic factors.

Long survival in gut lumen

Worm load and repeated infection important to disease severity

PARASITES AND DISEASES

Enterobius

![]() ENTEROBIUS VERMICULARIS (PINWORM): PARASITOLOGY

ENTEROBIUS VERMICULARIS (PINWORM): PARASITOLOGY

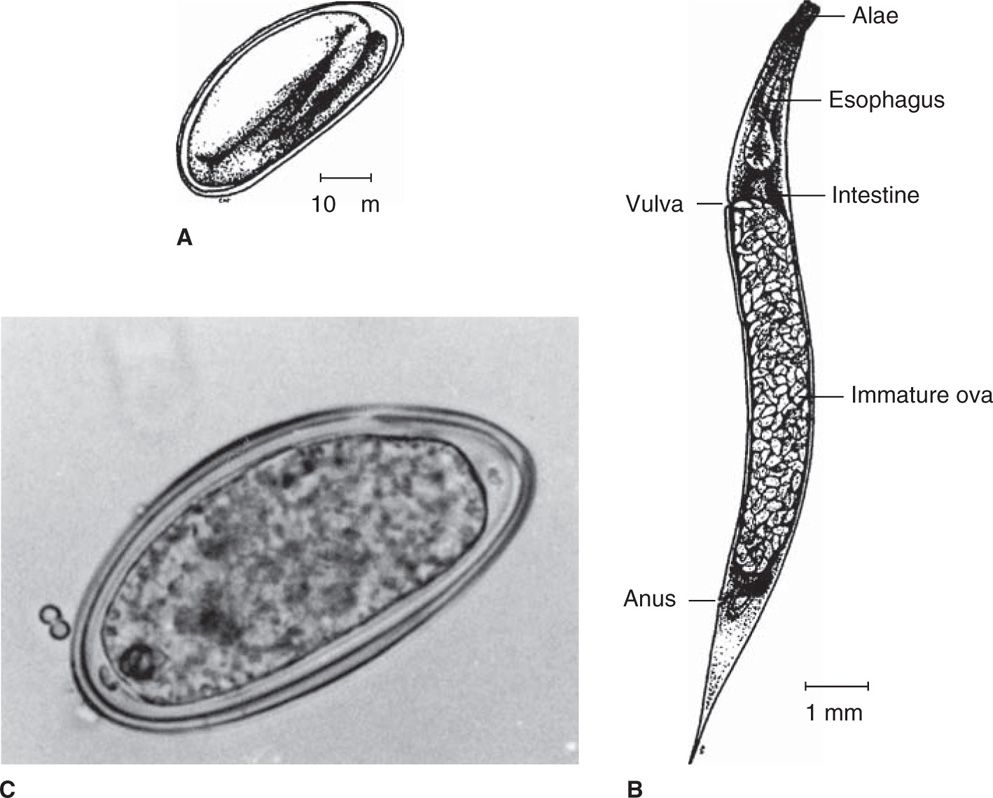

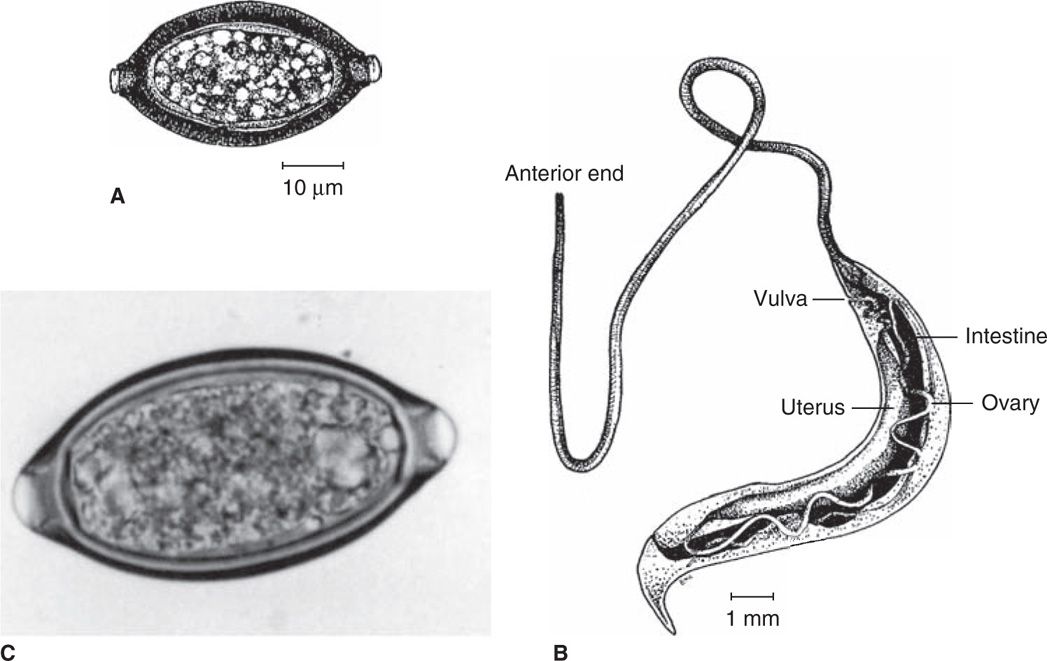

The adult female pinworm is 10 mm long, cream colored, with a sharply pointed tail; such characteristics have given rise to the common name pinworm, or threadworm. Running longitudinally down both sides of the body are small ridges that widen anteriorly to fin-like alae. The seldom-seen male is smaller (3 mm) and possesses a ventrally curved tail and copulatory spicule. The clear, thin-shelled, ovoid eggs are flattened on one side and measure 25 by 50 μn (Figure 54–1).

FIGURE 54–1. Enterobius vermicularis. A. egg structure. B. Structure of adult female pinworm. C. Embryonated egg recovered from stool. (C, reproduced with permission from Connor Dh, Chandler FW, Schwartz DQ, et al: Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Stamford CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.)

Common name is pinworm or threadworm

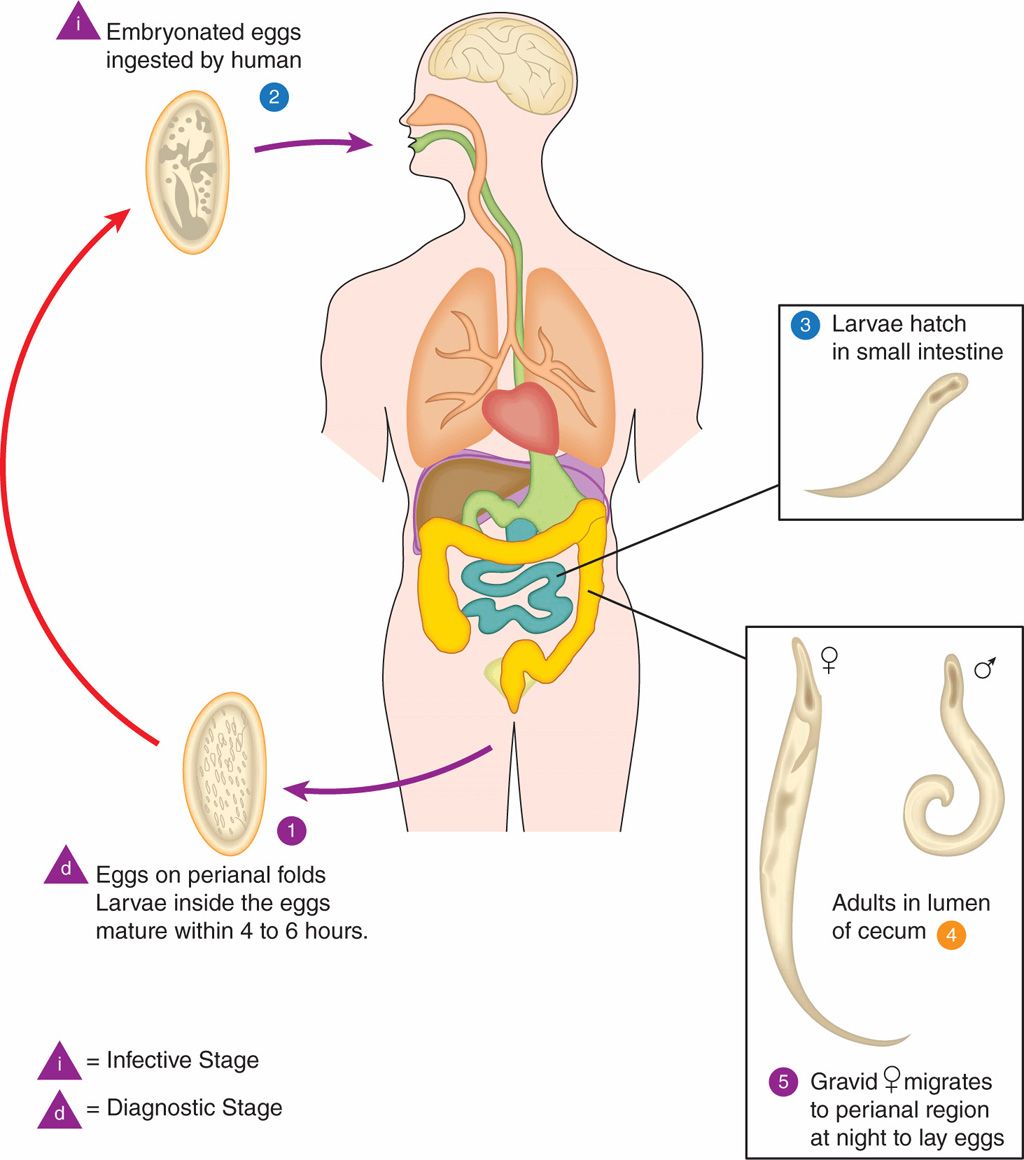

LIFE CYCLE (FIGURE 54–2)

Eggs are deposited on perianal folds  . Self-infection occurs by transferring infective eggs to the mouth with hands that have scratched the perianal area

. Self-infection occurs by transferring infective eggs to the mouth with hands that have scratched the perianal area  . Person-to-person transmission can also occur through handling of contaminated clothes or bed linens. Enterobiasis may also be acquired through surfaces in the environment that are contaminated with pinworm eggs (eg, curtains, carpeting). Some small number of eggs may become airborne and inhaled. These would be swallowed and follow the same development as ingested eggs. Following ingestion of infective eggs, the larvae hatch in the small intestine

. Person-to-person transmission can also occur through handling of contaminated clothes or bed linens. Enterobiasis may also be acquired through surfaces in the environment that are contaminated with pinworm eggs (eg, curtains, carpeting). Some small number of eggs may become airborne and inhaled. These would be swallowed and follow the same development as ingested eggs. Following ingestion of infective eggs, the larvae hatch in the small intestine  and the adults establish themselves in the colon

and the adults establish themselves in the colon  . The time interval from ingestion of infective eggs to oviposition by the adult females is about one month. The life span of the adults is about two months. Gravid females migrate nocturnally outside the anus and oviposit while crawling on the skin of the perianal area

. The time interval from ingestion of infective eggs to oviposition by the adult females is about one month. The life span of the adults is about two months. Gravid females migrate nocturnally outside the anus and oviposit while crawling on the skin of the perianal area  . The larvae contained inside the eggs develop (the eggs become infective) in 4 to 6 hours under optimal conditions

. The larvae contained inside the eggs develop (the eggs become infective) in 4 to 6 hours under optimal conditions  . Retroinfection, or the migration of newly hatched larvae from the anal skin back into the rectum, may occur but the frequency with which this happens is unknown.

. Retroinfection, or the migration of newly hatched larvae from the anal skin back into the rectum, may occur but the frequency with which this happens is unknown.

FIGURE 54–2. Enterobius vermicularis life cycle. [Redrawn from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).]

Enterobius has the simplest life cycle of the intestinal nematodes. The adult worms lie attached to the mucosa of the cecum, where the male inseminates the female. As her period of gravidity draws to a close, the female migrates down the colon, slips unobserved through the anal canal in the dark of the night, and deposits as many as 20 000 sticky eggs on the host’s perianal skin, bedclothes, and linens. The eggs are near maturity at the time of deposition and become infectious shortly thereafter. Handling of bedclothes or scratching of the perianal area to relieve the associated itching results in adhesion of the eggs to the fingers and fingernails; subsequently the eggs are ingested during eating or thumb sucking. Alternatively, the eggs may be shaken into the air (eg, during making of the bed), inhaled, and swallowed. The eggs subsequently hatch in the upper intestine, and the larvae migrate to the cecum, maturing to adults and mating in the process. The entire adult-to-adult cycle is completed in 2 weeks.

Adults inhabit cecum

Female transits anus at night to deposit eggs on perineum

Eggs infectious to host and others shortly after deposition

Ingested eggs hatch and larvae mature to adults in intestine

![]() ENTEROBIASIS

ENTEROBIASIS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The pinworm is the oldest and most widespread of the helminths. Eggs have been found in a 10 000-year-old coprolith, making this nematode the oldest demonstrated infectious agent of humans. It has been estimated to infect at least 200 million people worldwide, particularly children, including 40 million in the United States alone. Despite evidence that its prevalence is now decreasing in the United States, it remains the single most common cause of human helminthiasis in industrialized nations. Infection is more common among the young and poor, but may be found in any age or economic group.

Infects 30 to 40 million in the United States

The eggs are relatively resistant to desiccation and may remain viable in linens, bedclothes, or house dust for several days. Once infection is introduced into a household, other family members are often rapidly infected.

Hardy infective eggs

PATHOGENESIS AND IMMUNITY

The adult worms produce no significant intestinal pathology and do not appear to induce protective immunity.

ENTEROBIASIS: CLINICAL ASPECTS

ENTEROBIASIS: CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

Enterobius vermicularis seldom produces serious disease. Many carriers have no complaints at all, but when symptoms do develop, the most common presentation is pruritus ani (anal itching). This symptom is most severe at night and has been attributed to the migration of the gravid female. It may lead to irritability in children. In severe infections, the intense itching may lead to scratching, excoriation, and secondary bacterial infection. In female patients, the worm may enter the genital tract, producing vaginitis, granulomatous endometritis, or even salpingitis. It has also been suggested that migrating worms might carry enteric bacteria into the urinary bladder in young women, inducing acute bacterial cystitis. Although this worm is frequently found in the lumen of the resected appendix, it is doubtful that it plays a causal role in appendicitis. Perhaps the most serious effect of this common infection is the psychic trauma suffered by the economically advantaged when they discover that they, too, are subject to intestinal worm infection.

Nocturnal pruritus ani

Occasional infection of female genitourinary tract

DIAGNOSIS

Eosinophilia is usually absent. The diagnosis is suggested by the clinical manifestations and confirmed by the recovery of the characteristic eggs from the perianal skin. This is accomplished by applying the sticky side of cellophane tape to the mucocutaneous junction, then transferring the tape to a glass slide and examining the slide for eggs (Figure 54–1C) under the low-power lens of a microscope. Occasionally, adult females are seen by the parent of an infected child or recovered with the cellophane tape procedure.

Perianal cellophane tape test detects ova

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

Several highly satisfactory agents, including pyrantel pamoate and mebendazole, are available for treatment of enterobiasis. Many experts believe that all members of a family or other cohabiting group should be treated simultaneously. In severe infections, retreatment after 2 weeks is recommended. Although cure rates are high, reinfection is extremely common.

All family members may need treatment

Reinfection common

Trichuris

![]() TRICHURIS TRICHIURA (WHIPWORM): PARASITOLOGY

TRICHURIS TRICHIURA (WHIPWORM): PARASITOLOGY

The adult whipworm is 30 to 50 mm in length. The anterior two-thirds is thin and threadlike, whereas the posterior end is bulbous, giving the worm the appearance of a tiny whip. The tail of the male is coiled; that of the female is straight. The female produces 3000 to 10 000 oval eggs each day. They are of the same size as pinworm eggs, but have a distinctive thick brown shell with translucent knobs on both ends (Figure 54–3).

FIGURE 54–3. Trichuris trichiura. A. Egg structure. B. Structure of female adult whipworm. C. Embryonated egg with bipolar plugs from stool. (C, Reproduced with permission from Connor DH, Chandler FW, Schwartz DQ, et al: Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Stamford CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.)

Whipworm produces up to 10 000 eggs a day

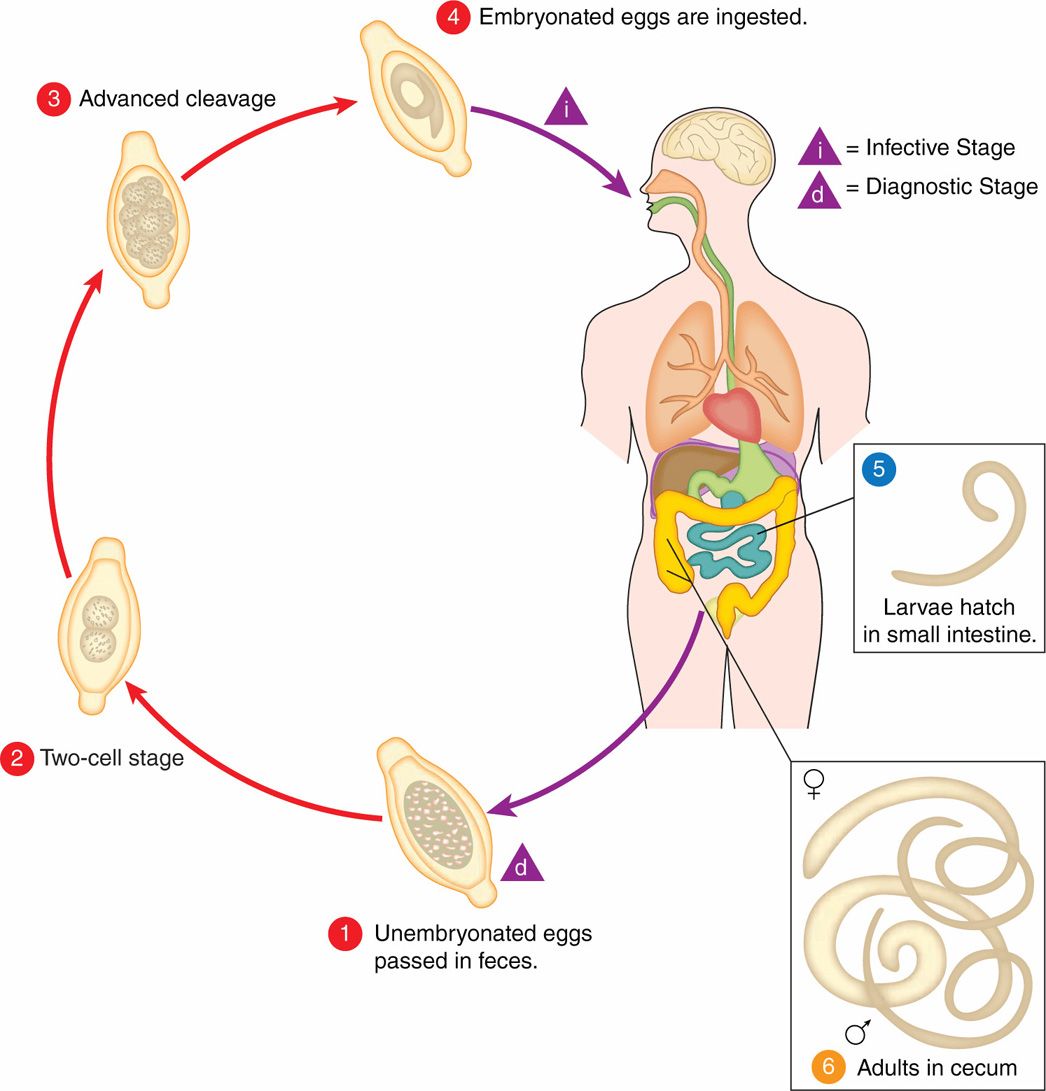

LIFE CYCLE (FIGURE 54–4)

The unembryonated eggs are passed with the stool  . In the soil, the eggs develop into a two-cell stage

. In the soil, the eggs develop into a two-cell stage  , an advanced cleavage stage

, an advanced cleavage stage  , and then they embryonate

, and then they embryonate  ; eggs become infective in 15 to 30 days. After ingestion (soil-contaminated hands or food), the eggs hatch in the small intestine, and release larvae

; eggs become infective in 15 to 30 days. After ingestion (soil-contaminated hands or food), the eggs hatch in the small intestine, and release larvae  that mature and establish themselves as adults in the colon

that mature and establish themselves as adults in the colon  . The adult worms (approximately 4 cm in length) live in the cecum and ascending colon. The adult worms are fixed in that location, with the anterior portions threaded into the mucosa. The females begin to oviposit 60 to 70 days after infection. Female worms in the cecum shed between 3000 and 20 000 eggs per day. The life span of the adults is about 1 year.

. The adult worms (approximately 4 cm in length) live in the cecum and ascending colon. The adult worms are fixed in that location, with the anterior portions threaded into the mucosa. The females begin to oviposit 60 to 70 days after infection. Female worms in the cecum shed between 3000 and 20 000 eggs per day. The life span of the adults is about 1 year.

FIGURE 54–4. Trichuris trichiura life cycle. [Redrawn from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).]

Trichuris trichiura has a life cycle slightly more complex than that of the pinworm. The adults live attached to the colonic mucosa by their thin anterior end. While retaining its position in the cecum, the gravid female releases its eggs into the lumen of the gut. These pass out of the body with the feces and, in poorly sanitized areas of the world, are deposited on soil. The eggs are immature at the time of passage and must incubate for at least 10 days (longer if soil conditions, temperature, and moisture are suboptimal) before they become fully embryonated and infectious. Once in this state, they are ingested unknowingly by the next human host—picked up on the hands of children at play, or by agricultural workers, or diners in areas where human feces are used as fertilizer, where raw fruits and vegetables may be contaminated and later eaten. After ingestion, the eggs hatch in the duodenum, and the released larvae mature for approximately 1 month in the small bowel before migrating to their adult habitat in the cecum.

Adults inhabit cecum and release eggs to lumen

Additional complexity: Eggs must mature in soil for 10 days

![]() TRICHURIASIS

TRICHURIASIS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although it is less widespread than the pinworm, the whipworm is a cosmopolitan parasite, infecting approximately 800 million people throughout the world. It is concentrated in areas where indiscriminate defecation and a warm, humid environment produce extensive seeding of soil with infectious eggs. In some communities in tropical climates, infection rates may be as high as 80%. Although the incidence is much lower in temperate climates, trichuriasis affects 2 million individuals throughout the rural areas of the southeastern United States. Here, it occurs primarily in family and institutional clusters, presumably maintained by the poor sanitary habits of toddlers and those with developmental delay. Although the intensity of infection is generally low, adult worms may live 4 to 8 years.

Associated with defecation on soil and warm, humid climate

Adult worms live for years

PATHOGENESIS AND IMMUNITY

Attachment of adult worms to the colonic mucosa and their subsequent feeding activities produce localized ulceration and hemorrhage (0.005 mL blood per worm per day). The ulcers provide enteric bacteria with a portal of entry to the bloodstream, and occasionally a sustained bacteremia results. A decrease in the prevalence of trichuriasis in the postadolescent period and the demonstration of acquired immunity in experimental animal infections suggest that immunity may develop in naturally acquired human infections. An IgE-mediated immune mucosal response is demonstrable in humans, but is insufficient to cause appreciable parasite expulsion.

Local colonic ulceration provides entry point to bloodstream for bacteria

TRICHURIASIS: CLINICAL ASPECTS

TRICHURIASIS: CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

Light infections of trichuriasis are asymptomatic. With moderate worm loads, damage to the intestinal mucosa may induce nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and stunting of growth. Occasionally, a child may harbor 800 adult worms or more. In these situations, the entire colonic mucosa is parasitized, with significant mucosal damage, blood loss, and anemia (Figure 54–5). This may cause a “dysentery syndrome” with bloody diarrhea that mimics infection with bacterial pathogens such as Shigella. Heavy worm burdens may cause tenesmus, the sensation that one needs to defecate continuously, and this may lead to prolapse of the rectum through the anus, particularly when the host is straining at defecation or during childbirth.

FIGURE 54–5. Whipworm infestation. Terminal ileum covered with adult Trichuris trichiura. (Reproduced with permission from Connor Dh, Chandler FW, Schwartz DQ, et al: Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Stamford CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree