OUTLINE

Definitions and Suspension Nomenclature

Desired Properties of a Suspension

Basic Steps in Compounding a Suspension

Stability and Beyond-Use Dating

Special Labeling Requirements for Suspensions

I. DEFINITIONS AND SUSPENSION NOMENCLATURE

A. Suspensions: “Suspensions are liquid preparations that consist of solid particles dispersed throughout a liquid phase in which the particles are not soluble” (1).

B. Other suspension nomenclature

1. Though the word suspension is now the USP-designated term for dosage forms that are solid-liquid dispersions, historically various other terms such as milk (e.g., milk of magnesia), magma (e.g., bentonite magma), lotion (e.g., hydrocortisone lotion), and syrup (e.g., doxycycline syrup) have been used as names for suspensions. Some terms, such as milk and magma, named specific types of suspensions, whereas some other terms were nonspecific as to physical system. For example, the term lotion has been used for solutions, suspensions, and liquid emulsions, and syrup could refer to either a solution or a suspension.

2. As was discussed at the beginning of Chapter 27, in 2002 the USP formed a group to work on simplifying and clarifying dosage form nomenclature. Under the system proposed by this group, dosage forms would be named by their route of administration (e.g., oral, topical) plus their physical system (e.g., tablet, solution, suspension) (2). For example, as of July 2007, the name White Lotion USP was changed to the more descriptive Zinc Sulfide Topical Suspension USP (3).

3. Because development and acceptance of and transition to a new nomenclature system will undoubtedly take many years, it is important for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians to understand new nomenclature but also recognize the various traditional terms used as names for dosage forms.

a. Milk: A traditional term used for some oral aqueous suspensions (1). The name comes from the fact that the dispersed solid was usually a white-colored inorganic compound that made the suspension appear like milk.

b. Magma: An older term used for suspensions of inorganic solids with a strong affinity for hydration, which resulted in a suspension with gel-like, thixotropic rheology (1). The solid could be a clay such as bentonite or kaolin or an inorganic/organic salt such as bismuth subsalicylate.

c. Lotion: Though in the past this term has been used for topical suspensions, emulsions, and solutions, the 2006 CDER Data Standards Manual states that the current definition is now limited to liquid emulsions for external application to the skin (4).

d. Syrup: Though the proposed USP nomenclature recommends elimination of this term, the CDER Data Standards Manual includes syrup as a designated dosage form and defines it as “an oral solution containing high concentrations of sucrose or other sugars; the term has also been used to include any other liquid dosage form prepared in a sweet and viscid vehicle, including oral suspensions” (2,4).

C. Wetting: When a liquid displaces air at the surface of a solid and the liquid spontaneously spreads over the surface of the solid, we say that wetting has occurred (5).

D. Wetting agents: Wetting agents are surfactants that, when dissolved in water, lower the contact angle between the surface of the solid and the aqueous liquid and aid in displacing the air phase at the surface and replacing it with the aqueous liquid phase (6).

E. Surfactants: Surfactants are ions or molecules that are adsorbed at interfaces (6). Their molecular structures contain both a hydrophilic and hydrophobic portion. They orient themselves at interfaces so as to reduce the interfacial free energy produced by the presence of the interface (7). For a detailed discussion of surfactants, see Chapter 20, Surfactants and Emulsifying Agents.

II. USES OF SUSPENSIONS

A. Oral suspensions

1. There is often a need to administer solid drugs orally in liquid form to patients who cannot swallow tablets or capsules. These patients include adults who cannot swallow solid dosage forms, infants or children who have not yet learned how to swallow whole tablets or capsules, nonambulatory patients with nasogastric tubes, and geriatric patients who no longer have the ability to swallow solid oral dosage units.

2. A manufactured liquid product should be used if available because the manufacturer has conducted stability and bioavailability testing on the product. Though pharmaceutical companies now manufacture a large number of oral liquid drug products, many therapeutic agents are still not available in liquid dosage forms. Furthermore, in recent years there have been significant problems with product shortages, including oral liquids. When a manufactured product is unavailable, pharmacists are often asked to compound oral liquid preparations for their patients who need them.

3. Liquid preparations can be made as solutions, suspensions, or emulsions, depending on the physical state and solubility properties of the active ingredients. For drugs that are soluble in water or a cosolvent system that is appropriate for oral use, oral solutions are made; oral and topical solutions are discussed in Chapter 27. If the active ingredient is an immiscible liquid, a liquid emulsion may be formulated; liquid emulsions are described in Chapter 29. When a liquid preparation is needed for a drug that is an insoluble solid, a suspension is formulated. In some cases, an insoluble form of a drug is made intentionally because the drug in soluble form has poor stability or a bad taste.

B. Suspensions for topical use and for administration to mucous membranes

1. As with oral suspensions, a manufactured product should be used if available.

2. Often, topical liquid preparations require compounding by the pharmacist because dermatologists find it desirable therapeutically to create formulas customized for a specific patient with a particular skin condition. Often these preparations are liquid-dispersed systems; numerous examples of dermatologic suspensions are given in this chapter, and two topical liquid emulsions are described in Chapter 29.

3. Suspensions are also administered to mucous membranes, including nasal, eye, ear, and rectal tissues. Though otic and rectal suspensions can be made with relative ease in the pharmacy, nasal and ophthalmic suspensions are not commonly compounded because these are required to be sterile, and this requires steam sterilization as bacterial filtration would remove the active suspended ingredients.

C. Injectable suspensions

1. As with ophthalmic and nasal products, injectable suspensions are required to be sterile, and most of these products are furnished by the manufacturer as sterile suspensions ready for administration.

2. In some cases, the manufacturer furnishes the active ingredient(s) and necessary excipients in a sterile, sealed vial, and the pharmacist, pharmacy technician, or nurse reconstitutes the suspension by adding sterile water or other sterile diluent to the vial at the time of dispensing or administration.

III. DESIRED PROPERTIES OF A SUSPENSION

A. Fine, uniform-sized particles

1. Very fine particles are desirable for both topical and oral suspensions. Particles in suspensions usually range from 0.5 to 3 microns (μm) in diameter.

a. Uniform, finely divided particles give optimal dissolution and absorption. This is particularly important for suspensions that are intended for systemic use.

b. A smooth, nongritty preparation is essential for patient acceptance. This is true for both topical and internal-use preparations.

c. Small, uniform-sized particles are also needed to give suspensions with acceptable rates of settling.

2. Desired particle size is achieved through choice of drug form, selection of appropriate compounding equipment, and good compounding techniques.

a. Choice of drug form

(1) If a prescription or drug order specifies a certain form of a drug, that form must be used unless the prescriber is consulted. For example, if the prescription lists precipitated sulfur as an ingredient, that form should be used in the formulation.

(2) In general, if a drug or chemical is available in more than one form and no form is specified in the drug order, choose the form that has the finest particle size (e.g., boric acid powder rather than boric acid crystals, colloidal sulfur rather than precipitated sulfur). Remember, however, that very fine particles have a high degree of surface-free energy, and very fine particles have an increased tendency to aggregate and eventually fuse together into a nondispersible cake (8). For a complete discussion of this subject and factors to consider and control, consult a book on physical pharmacy.

(3) The form of drug or chemical used in compounding should be specified on the face of the prescription document or on the master formulation record and the record of compounding. This ensures product uniformity with each prescription refill.

b. Compounding equipment and technique

(1) Suspensions are usually made in the pharmacy using mortars and pestles. Choice of mortar type depends on both the characteristics of the ingredients and the volume of the preparation.

(2) Proper technique for reducing particle size is discussed in section V. B. of Chapter 25, Powders.

(3) Some pharmacists have found that they can ensure more uniform particles of the desired size for dispersions by passing the prepared powder through a sieve. A mesh size of the range 35 to 45 is considered adequate for suspensions. An example of this is in the USP compounding monograph for Ketoconazole Oral Suspension, which states, “If Tablets are used, finely powder the Tablets such that they pass through a 40-mesh or 45-mesh sieve” (3). Pharmaceutical sieves and mesh sizes are described and discussed in section IV. E. of Chapter 25. Small sieve nests with mesh sizes suitable for compounding can be ordered from some vendors of compounding supplies.

SIEVING A POWDER

B. Uniform dispersion of the particles in the liquid vehicle

Because, in a suspension, the solid does not dissolve, the solid should be evenly dispersed in the liquid vehicle. This ensures a uniform mixture and a uniform dose. To accomplish this, (i) the insoluble powder must be properly wet: that is, the air on the surface of the powder particles must be displaced by liquid, and (ii) any powder aggregates must be broken down to fine, primary particles and these coated with vehicle.

1. If the liquid vehicle is one with a low surface tension, the liquid will easily wet the solid.

2. In most situations, however, water constitutes all or part of the dispersing liquid; water has a high surface tension and does not easily wet many solids, especially hydrophobic drugs or chemicals. When water is a component of the liquid vehicle, special additives, techniques, or order of mixing may be needed to create a uniform suspension. The ingredients and procedure depend on the nature of the solid phase, the other ingredients in the formulation, and the intended route of administration.

a. Insoluble, hydrophilic powders: These are easily wet by water and other water-miscible liquids used for pharmaceutical preparations. Though no special additives are necessary for wetting, the usual procedure is to initially mix the powders with a small amount of liquid vehicle to form a thick paste. In compounding, this is usually done by trituration using a mortar and pestle. This facilitates the desired efficient shearing of the solid particles, the breakup of powder aggregates, and the intimate mixing with the vehicle to give a smooth uniform suspension.

(1) Two common examples of bulk powders in this class are zinc oxide and calamine. The procedure for suspending these powders is illustrated with Calamine Topical Suspension USP, which is described in Sample Prescription 28.1.

(2) Most manufactured tablets, when used as ingredients for suspensions, are also easily wet by water. They have been formulated with tablet disintegrants, which absorb water to enhance the breakup of the tablet in the gastrointestinal tract. Tablet material is readily wet by a small amount of water or glycerin. After the tablets are allowed to soften, they are triturated to a smooth paste using a mortar and pestle. This is illustrated in Sample Prescription 28.5, which is described in this chapter and demonstrated on the CD that accompanies this book.

b. Insoluble, hydrophobic powders: These powders are not easily wet by water. To wet such a solid, either a water-miscible liquid with a low surface tension may be used, or a wetting agent may be added to the water to reduce its surface tension. In both cases, remember to consider the route of administration when selecting an additive to improve wetting; additives to oral suspensions must be approved for internal use.

(1) Use of water-miscible liquids with low surface tension for wetting solids: Because water has a surface tension of 72.8 dynes/cm (at 20°C) and glycerin has a surface tension of 63.4 dynes/cm, glycerin is a better wetting medium for hydrophobic drugs than is water. Examples of liquids used for wetting hydrophobic solids include glycerin, alcohol, propylene glycol, polyethylene glycol, any liquid surfactant, or an ingredient containing a surfactant. The use of liquids of this type for wetting a hydrophobic powder is illustrated on Color Plate 5 and with the compounding procedures for Sample Prescriptions 28.2 and 28.4.

(2) Use of wetting agents: A wetting agent is a surfactant that, when added to water, improves its ability to wet hydrophobic powders. Examples include soaps such as sodium stearate, detergents such as sodium lauryl sulfate and dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (docusate sodium), and nonionic surfactants such as polysorbate 80 (Tween 80). These are described in Chapter 20, Surfactants and Emulsifying Agents.

c. If possible, an ingredient that is already in the drug order should be used for wetting the insoluble solid. If there is no suitable liquid or surfactant in the formulation, use professional judgment to decide what, if anything, should be added. A small amount of glycerin, alcohol, or propylene glycol is often helpful. A convenient source of surfactant in a pharmacy is the stool softener docusate sodium. Docusate sodium is available formulated both in a liquid and in soft-gelatin capsules. To use a capsule, cut through the soft-gelatin with a razor blade and express the contents into a small amount of water.

C. Slow settling of particles (that is, slow sedimentation rate)

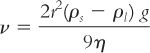

Though it is impossible to completely prevent settling of solid particles in a suspension, the rate of sedimentation can be controlled. Stokes’ Law provides useful information in determining what parameters of a suspension may be controlled to retard the sedimentation rate of particles in a suspension.

EXTRACTING SURFACTANT DOCUSATE NA FROM A SOFT-SHELL CAPSULE

where:

Though gravitational acceleration (g) is a constant and the density of the solid (ρs) cannot be changed, the other factors in Stokes’ Law can be manipulated to minimize sedimentation rate (ν):

1. r: The particle size should be as small and uniform as possible. As discussed previously, this is controlled through choice of drug form and through proper use of compounding equipment and technique.

2. ρl: The density of the liquid may be increased. If the density of the liquid could be made equal to the density of the solid, the term (ρs – ρl) becomes zero, the sedimentation rate becomes zero, and the suspended particles do not settle. Though this is rarely achieved (e.g., zinc oxide has a density of 5.6 g/cm3, whereas water has a density of 1.0 g/cm3), the density of the medium can be manipulated to improve the sedimentation rate.

a. For oral suspensions, the density of the liquid can be increased by adding sucrose, glycerin, sorbitol, or other soluble or miscible, orally acceptable additives. Glycerin has a density of 1.25 g/cm3, Syrup NF has a density of 1.3 g/cm3, and Sorbitol 70% has a density of 1.285 g/cm3.

b. For topical suspensions, any inactive, soluble, or miscible ingredient that is approved for topical use and that would increase density is acceptable.

3. η: The viscosity of the liquid medium may be increased by adding a viscosity-inducing agent, such as acacia, tragacanth, methylcellulose, sodium carboxymethylcellulose, carbomer, colloidal silicon dioxide, bentonite, or Veegum. Detailed information on viscosity-inducing agents and their use is given in Chapter 19, Viscosity-Inducing Agents.

D. Ease of redispersion when the product is shaken

1. Solids should not form a hard “cake” on the bottom of the bottle when the preparation is allowed to stand.

a. As was stated previously, very fine particles have an increased tendency to aggregate and eventually fuse together into a nondispersible cake because of the high surface-free energy associated with very fine particles. This factor should be considered in selecting ingredients for suspensions.

b. Because caking requires time to develop, a conservative beyond-use date should be considered for suspensions at risk for this problem.

2. The preparation should be sufficiently fluid so that redispersion of settled particles is easily accomplished with normal shaking of the container. The liquid should also pour freely from the container when a dose is to be administered or applied. Judicious use of viscosity-inducing ingredients when formulating suspensions is important in achieving this goal.

3. One special formulation technique, flocculation, is useful in producing suspensions that readily redisperse.

a. Flocculation gives a controlled lacework-like structure of particles held together by weak bonds. These weak bonds hold the particles in the structure when the suspension is at rest but break apart easily when the suspension is shaken.

b. This technique is often used in the pharmaceutical industry for manufactured suspension products. Some viscosity-inducing agents, such as bentonite and xanthan gum, form flocculated systems; these are available to the pharmacist and are useful as suspending agents in compounding.

c. Various manufactured suspending vehicles, such as Ora-Plus and Suspendol-S, and the official NF suspending vehicles, Vehicle for Oral Suspension, Bentonite Magma, Suspension Structured Vehicle, and Sugar-Free Suspension Structured Vehicle, are examples of flocculated systems that are helpful in making suspensions that settle slowly but that are easily redispersed on shaking. A sample of manufactured suspension vehicles for compounding is illustrated in Color Plate 6.

IV. BASIC STEPS IN COMPOUNDING A SUSPENSION

A. Check all doses and concentrations for appropriateness.

B. Review Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDSs) for each bulk ingredient to determine safety procedures and recommended personal protective equipment to use when compounding the preparation.

C. Select the desired form for each solid ingredient. In some cases, this form depends on availability. For example, some drugs may be available only as manufactured tablets or capsules.

D. Calculate the amount of each ingredient required for the formulation. If tablets or capsules are used as a source for an active ingredient, the necessary calculations and procedure vary depending on the need for either a whole number or a fractional number of units.

1. If a whole number of tablets or capsules is needed, determine the correct number of dosage units to add. There is no need to first weigh the tablets or capsule contents. For an illustration of this procedure, see Sample Prescription 28.5, which is also demonstrated on the CD that accompanies this book.

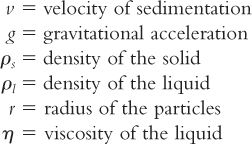

2. If a fractional number of dosage units are needed, follow the steps given here. Remember that tablets and capsule powder contain added formulation ingredients, and this must be considered when determining the weight of tablet or capsule material to use in making the suspension. (See Sample Prescriptions 25.5 and 25.6 in Chapter 25 and Sample Prescription 28.6 in this chapter for examples of this procedure.)

a. Determine the average weight of a tablet or the powder contents of a capsule. If only one unit is needed, weigh that unit or, for a capsule, the contents of that unit. Remember, for capsules you will not be adding the capsule shell to the suspension, so this should not be weighed.

b. Use the equation given here to determine the amount of crushed tablet or capsule powder needed:

E. Weigh, measure, or count (for tablets or capsules) the calculated amount of each ingredient needed. If using a fractional number of tablets or capsules, crush or empty the appropriate number of units and weigh the amount calculated earlier.

F. Use the techniques for reducing particle size and mixing the powders as described in Chapter 25, Powders.

G. Wet the powders by adding a small amount of liquid vehicle to the powders in a mortar and triturating so that a thick, uniform paste is obtained. Steps F and G may be combined if appropriate.

H. Add additional liquid vehicle in portions with trituration until a smooth, uniform preparation is obtained.

I. Transfer the suspension to its dispensing container. To ensure complete transfer of the suspended solid active ingredients, use some of the remaining vehicle to rinse the material from the mortar into the dispensing container. A powder funnel with a large diameter stem may be used to facilitate the transfer.

J. Add sufficient vehicle to the dispensing container to make the preparation the desired volume.

K. Some pharmacists recommend that suspensions be homogenized for maximum uniformity and improved physical stability. This can be accomplished by passing the suspension through a hand homogenizer or by using a high-speed blender or homogenizer. If this is done, you will need to make extra suspension to allow for loss of preparation in the equipment.

V. STABILITY AND BEYOND-USE DATING

A. Physical stability of the system: Both maintenance of small particles and ease of redispersion are essential to the physical stability of the system. Because suspensions are physically unstable systems, beyond-use dates for these preparations should be conservative.

B. Chemical stability of the ingredients

1. For ingredient-specific information, check references such as those listed in Chapter 37. Examples are illustrated with the prescription ingredients in each of the sample prescriptions at the end of this chapter.

2. USP Chapter 〈795〉 recommends a maximum 14-day beyond-use date for water-containing liquid preparations made with ingredients in solid form when the stability of the ingredients in that specific formulation is not known (9). This assumes that the preparation will be stored at cold temperature (e.g., a refrigerator) (9); though this works well for oral suspensions, topical preparations are usually stored at room temperature, and the beyond-use date may need adjustment to compensate for this higher storage temperature. Concerns for chemical stability of labile drugs may necessitate greater limits on beyond-use dates.

3. USP Chapter 〈1151〉 states that suspensions should be stored and dispensed in tight containers (1).

4. Though technically it is very easy to make oral suspensions from crushed tablets and available suspending vehicles, care should always be used in checking and verifying the stability and the beyond-use date of the compounded preparation.

C. Microbiologic stability

1. USP Chapter 〈1151〉 states that suspensions should contain preservatives to protect against bacteria, yeasts, and molds (1). If antimicrobial ingredients are part of the prescribed formulation, extra preservatives are not needed.

2. Antimicrobial agents and their proper use are discussed in Chapter 16, and consideration of preservatives is presented in each of the following sample prescription formulations.

3. Though solubility of the preservative is a major concern when selecting a preservative for a solution, suspensions are disperse systems, so precipitation of a preservative in a suspension is acceptable; a saturated solution of the preservative will be maintained, and this should be sufficient for preservation.

VI. SPECIAL LABELING REQUIREMENTS FOR SUSPENSIONS

A. All suspensions are disperse systems and require a “SHAKE WELL” auxiliary label.

B. External use suspensions should be labeled “FOR EXTERNAL USE ONLY.”

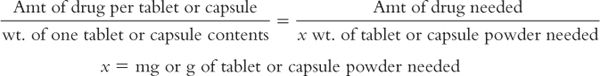

CASE: Professor George Helmholtz is a 160-lb, 5’11’’ tall, 68-year-old man who has recently retired from his university faculty position. He and his wife have purchased a lake cottage, and today, within a few hours of wading in the lake as he put in the pier for his boat, he found multiple small, defined red bites on his feet, ankles, and calves, and he reports that they itch “like crazy.” He has gone to a local physician who has diagnosed “lake itch.”This is caused by a fluke that is common to the lakes in the area. Though self-limiting, the bites are highly irritating, and the only therapy is symptomatic treatment of the itching with a soothing lotion that contains on effective local anesthetic.

MASTER COMPOUNDING FORMULATION RECORD

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree