Patient Story

A 44-year-old HIV-positive Hispanic man presented with painful herpes zoster of his right forehead (Figure 125-1). He was particularly worried because his right eye was red, painful, and very sensitive to light (Figure 125-2). On physical examination there was significant conjunctival injection, corneal punctate epithelial erosions, and clouding, and a small layer of blood in the anterior chamber (hyphema). The pupil was somewhat irregular. Along with the hyphema and ciliary flush, this indicated an anterior uveitis. The patient had a unilateral ptosis on the right side with limitations in elevation, depression, and adduction of the eye secondary to cranial nerve III palsy from the zoster. The patient was immediately referred to ophthalmology and the anterior uveitis, corneal involvement, and cranial nerve III palsy were confirmed. The ophthalmologist started the patient on topical ophthalmic preparations of erythromycin, moxifloxacin, prednisolone, and atropine. Oral acyclovir was also prescribed. Unfortunately, the patient did not return for follow up until 6 months later when he returned to the ophthalmologist with significant corneal scarring (Figure 125-3). The patient is currently on a waiting list for a corneal transplantation.

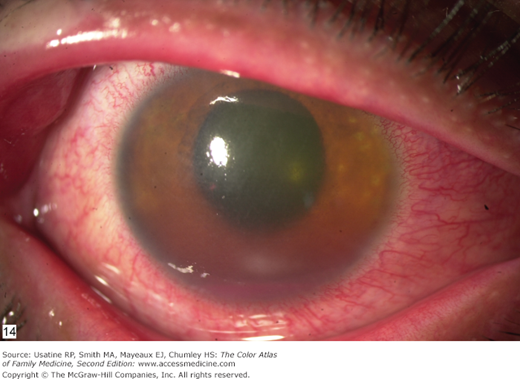

Figure 125-2

Acute zoster ophthalmicus of the same patient with conjunctival injection, corneal punctation (keratitis), and a small layer of blood in the anterior chamber (hyphema). A diagnosis of anterior uveitis was suspected based on the irregularly shaped pupil, the hyphema, and ciliary flush. A slit-lamp examination confirmed the anterior uveitis (iritis).

Introduction

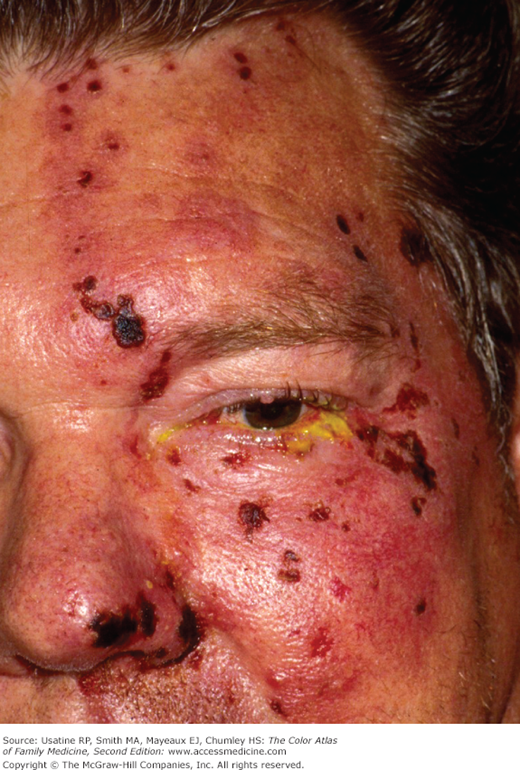

Herpes zoster is a common infection caused by varicella-zoster virus, the same virus that causes chickenpox. Reactivation of the latent virus in neurosensory ganglia produces the characteristic manifestations of herpes zoster (shingles). Herpes zoster outbreaks may be precipitated by aging, poor nutrition, immunocompromised status, physical or emotional stress, and excessive fatigue. Although zoster most commonly involves the thoracic and lumbar dermatomes, reactivation of the latent virus in the trigeminal ganglia may result in herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) (Figures 125-1, 125-2, 125-3, 125-4, 125-5, 125-6).

Figure 125-4

This 5-year-old girl had herpes zoster involving the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve. Note the vesicles and bullae on the forehead and eyelid and the crust on the nasal tip (Hutchinson sign). Fortunately, she did not have ocular complications and her case of zoster fully healed with oral acyclovir and acyclovir eye ointment. (Courtesy of Amor Khachemoune, MD.)

Figure 125-5

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus involving the first and second branch of the trigeminal nerve and the eyelids. There is conjunctival hyperemia and purulent left eye discharge. The nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve is involved, producing the black crusting on the tip of the nose. (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Epidemiology

- Incidence rates of HZO complicating herpes zoster range from 8% to 56%.1

- Ocular involvement is not correlated with age, gender, or severity of disease.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Serious sequelae may occur including chronic ocular inflammation, vision loss, and disabling pain. Early diagnosis is important to prevent progressive corneal involvement and potential loss of vision.2

- Because the nasociliary branch of the first (ophthalmic) division of the trigeminal (fifth cranial) nerve innervates the globe (Figure 125-7), the most serious ocular involvement develops if this branch is involved.

- Classically, involvement of the side of the tip of the nose (Hutchinson sign) has been thought to be a clinical predictor of ocular involvement via the external nasal nerve (Figures 125-4 and 125-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree