Dean, Philadelphia College of

Pharmacy and Science (1966)1

Health care and the profession of pharmacy have changed enormously since Dr. Tice articulated this vision more than 35 years ago. The role of the pharmacy technician has like-wise undergone substantial change. Technicians have increased in number. They may access a wide array of training opportunities, some of which are formal academic programs that have earned national accreditation. Technicians may now seek voluntary national certification as a means to demonstrate their knowledge and skills. State boards of pharmacy are increasingly recognizing technicians in their pharmacy practice acts.

Nonetheless, Dr. Tice’ vision remains unrealized. Although pharmacy technicians are employed in all pharmacy practice settings, their qualifications, knowledge, and responsibilities are markedly diverse. Their scope of practice has not been sufficiently examined. Basic competencies have not been articulated. Standards for technician training programs are not widely adopted. Board regulations governing technicians vary substantially from state to state.

Is there a way to bring greater uniformity in technician competencies, education, training, and regulation while ensuring that the technician work force remains sufficiently diverse to meet the needs and expectations of a broad range of practice settings? This is the question that continues to face the profession of pharmacy today as it seeks to fulfill its mission to help people make the best use of medications.

The purpose of this paper is to set forth the issues that must be resolved to promote the development of a strong and competent pharmacy technician work force. Helping pharmacists to fulfill their potential as providers of pharmaceutical care would be one of many positive outcomes of such a development. The paper begins with a description of the evolution of the role of pharmacy technicians and of their status in the work force today. The next section sets forth a rationale for building a strong pharmacy technician work force. The paper then turns to three issues that are key to realizing the pharmacy technician’ potential: (1) education and training, (2) accreditation of training institutions and programs, and (3) certification. Issues relating to state regulation of pharmacy technicians are then discussed. The paper concludes with a call to action and a summary of major issues to be resolved.

Many of the issues discussed in this report were originally detailed in a white paper developed by the American Pharmaceutical Association (APhA) and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), which was published in 1996.2 For this reason, this paper focuses primarily on events that have occurred since that time. Other sources used in the preparation of this paper include Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports,3,4 report to the U.S. Congress on the pharmacy work force,5 and input from professional associations representing pharmacists and technicians as well as from educators, regulators, and consumers.

The Pharmacy Technician: Past to Present

A pharmacy technician is “an individual working in a pharmacy [setting] who, under the supervision of a licensed pharmacist, assists in pharmacy activities that do not require the professional judgment of a pharmacist.”6 The technician is part of a larger category of “supportive personnel,” a term used to describe all non-pharmacist pharmacy personnel.7

There have been a number of positive developments affecting pharmacy technicians in the past decade, including national certification, the development of a model curriculum for pharmacy technician training, and greater recognition of pharmacy technicians in state pharmacy practice acts. The role of the pharmacy technician has become increasingly well defined in both hospital and community settings. Technicians have gained greater acceptance from pharmacists, and their numbers and responsibilities are expanding.8–11 They are starting to play a role in the governance of state pharmacy associations and state boards of pharmacy. Yet more needs to be done. There is still marked diversity in the requirements for entry into the pharmacy technician work force, in the way in which technicians are educated and trained, in the knowledge and skills they bring to the workplace, and in the titles they hold and the functions they perform.12,13 absence of uniform national training standards further complicates the picture. Because of factors such as these, pharmacists and other health professionals, as well as the public at large, have varying degrees of understanding and acceptance of pharmacy technicians and their role in health care delivery.

An awareness of developments relevant to pharmacy technical personnel over the last several decades is essential to any discussion of issues related to current and future pharmacy technicians.14,15 Policy statements of a number of national pharmacy associations are listed in the appendix. A summary of key events of the past half century follows.

1950s–1990s. Beginning in the late 1950s, hospital pharmacy and ASHP took the lead in advocating the use of pharmacy technicians (although the term “pharmacy technician” had not yet come into use), in developing technician training programs, and in calling for changes needed to ensure that the role of technicians was appropriately articulated in state laws and regulations.16 Among the initial objectives was to make a distinction between tasks to be performed by professional and nonprofessional staff in hospital and community settings. This was largely accomplished by 1969.14,17

In the community pharmacy sector, chain pharmacies supported the use of pharmacy technicians and favored on-the-job training. By contrast, the National Association of Retail Druggists (NARD, now the National Community Pharmacist Association [NCPA]), in 1974, stated its opposition to the use of technicians and other “subprofessionals of limited training” out of concern for public safety.14

Largely because of its origins, technician practice was initially better defined and standardized in hospitals than in community pharmacies. As the need for technicians in both settings became increasingly apparent, however, many pharmacists and pharmacy educators began to call for collaborative discussions and greater standardization on a number of issues related to pharmacy technicians, and in recent years, progress has been made toward this goal.

The Pharmacy Technician Work Force Today. Based on Pharmacy Technician Certification Board (PTCB) and Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimates, there are as many as 250,000 pharmacy technicians in the United States.8,18 This is a significant increase over the 1996 estimate of 150,000.2 BLS predicts that pharmacy technician employment will grow by 36% or more between 2000 and 2010.8 This percentage of growth is “much faster than the average for all occupations,” but in line with a majority of other supportive personnel in the health care sector.

Pharmacy technicians work in a wide variety of settings, including community pharmacies (approximately 70% of the total work force), hospitals and health systems (approximately 20%), long-term-care facilities, home health care agencies, clinic pharmacies, mail-order pharmacies, pharmaceutical wholesalers, managed care organizations, health insurance companies, and medical computer software companies.8 The 2001 Schering Report found that 9 out of 10 community pharmacies employ pharmacy technicians.10 Recent studies conducted in acute care settings indicate that this figure is nearly 100% for the hospital sector.19

What functions do technicians perform? Their primary function today, as in decades past, is to assist with the dispensing of prescriptions. A 1999 National Association of Chain Drug Stores (NACDS)/Arthur Andersen study revealed that, in a chain-pharmacy setting, pharmacy technicians’ time was spent on dispensing (76%), pharmacy administration (3%), inventory management (11%), disease management (<1%), and miscellaneous activities, including insurance-related inquiries (10%).21 Surveys conducted by PTCB have yielded similar results.18,21 The nature of dispensing activities may be different in a hospital than in a community pharmacy. In hospitals, technicians may perform additional specialized tasks, such as preparing total parenteral nutrition solutions, intravenous admixtures, and medications used in clinical investigations and participating in nursing-unit inspections.22

In the past, pharmacists have traditionally been reluctant to delegate even their more routine work to technicians.14 The 2001 Schering Report concluded that, in the past five years, pharmacists have become more receptive to pharmacy technicians. Indeed, much has changed in the scope of potential practice activities for pharmacy technicians and pharmacy’s perception of the significant role technicians might play.10,22 New roles for pharmacy technicians continue to emerge as a result of practice innovation and new technologies.9,11 Despite their expanded responsibilities, many technicians believe that they can do more. For example, one study reported that 85% of technicians employed in chain pharmacies, compared with 58% of those working in independent pharmacies, felt that their knowledge and skills were being used to the maximum extent.10

Pharmacy Technicians: The Rationale

Several developments in health care as a whole, and in pharmacy in particular, have combined to create an increasing demand for pharmacy technicians. Three of significant importance are the pharmacist work force shortage, the momentum for pharmaceutical care, and increased concern about safe medication use.

Pharmacist Work Force Shortage. In 1995, a report by the Pew Health Professions Commission predicted that automation and centralization of services would reduce the need for pharmacists and that the supply of these professionals would soon exceed demand.23 The predicted oversupply has failed to materialize; in fact, there is now a national shortage of pharmacists. A 2000 report of the federal Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) stated, “While the overall supply of pharmacists has increased in the past decade, there has been an unprecedented demand for pharmacists and pharmaceutical care services, which has not been met by the currently available supply.”5 The work force shortage is affecting all pharmacy sectors. Ongoing studies (by the Pharmacy Manpower Project and others) indicate that the pharmacy personnel shortages will not be solved in the short term.24

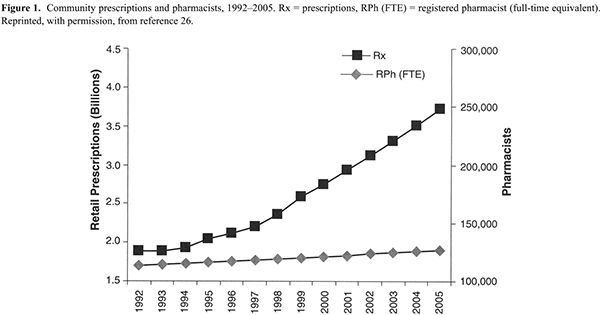

For pharmacy practitioners, the results of the work force shortage are clear: more work must be done with fewer pharmacist staff. Between 1990 and 1999, the number of prescriptions dispensed in ambulatory care settings increased by 44%, while the number of active pharmacists per 100,000 people increased by only about 5%.5 Chain pharmacists now fill an average of 86 prescriptions during a normal shift—a 54% increase since 1993.25 NACDS and IMS HEALTH estimate that, between 1999 and 2004, the number of prescriptions will increase by 36% while the number of pharmacists will increase by only 4.5% (Figure 1).26

Faced with greater numbers of prescriptions to dispense, pharmacists have less time to counsel patients. Working conditions and schedules have deteriorated, and job-related stress has risen.10 Professional satisfaction has diminished. Perhaps most ominous, fatigue and overwork increase the potential for medication errors.5,27

Increased use of technicians is one obvious way of reducing workload pressures and freeing pharmacists to spend more time with patients. A white paper issued in 1999 by APhA, NACDS, and NCPA emphasized the need for augmenting the pharmacist’s resources through the appropriate use of pharmacy technicians and the enhanced use of technology.28

The situation in pharmacy is not unique. A report from the IOM concluded that the health care system, as currently structured, does not make the best use of its resources.4 Broader use of pharmacy technicians, in itself, will not solve the pharmacist work force crisis. It would ensure, however, that the profession makes better use of existing resources.

Momentum for Pharmaceutical Care. More than a decade ago, Hepler and Strand29 expressed the societal need for pharmaceutical care. Since that time, the concept has been refined, and its impact on the health care system and patient care has been documented. Studies have shown that pharmaceutical care can improve patient outcomes, reduce the incidence of negative therapeutic outcomes, and avoid the economic costs resulting from such negative outcomes.30–33 Nonetheless, other studies indicate that pharmacists continue to spend much of their time performing routine product-handling functions.19,20 Widespread implementation of pharmaceutical care, a goal for the entire profession, has been difficult to achieve thus far.

Technicians are instrumental to the advancement of pharmaceutical care. As Strand34,35 suggested, prerequisites to successful implementation of pharmaceutical care include enthusiastic pharmacists, pharmacy supportive personnel willing to work in a pharmacy where dispensing is done by technicians rather than pharmacists, and a different mindset i.e., the pharmacist will no longer be expected to “count and pour” but to care for patients.

In other words, implementation of pharmaceutical care requires a fundamental change in the way pharmacies operate. Pharmacists must relinquish routine product-handling functions to competent technicians and technology. This is a difficult shift for many pharmacists to make, and pharmacists may need guidance on how to do it. For example, they may need training in how to work effectively with technicians. Recognizing this need, some practice sites have developed successful practice models of pharmacy technicians working with pharmacists to improve patient care. Several of these sites have been recognized through PTCB’s “Innovations in Pharmaceutical Care Award.”36

Safe Medication Use. Used inappropriately, medications may cause unnecessary suffering, increased health care expenditures, patient harm, or even death.33 Ernst and Grizzle37 estimated that the total cost of drug-related morbidity and mortality in the ambulatory care setting in 2000 was more than $177 billion—more than the cost of the medications themselves. They stressed the urgent need for strategies to prevent drug-related morbidity and mortality.

The problems associated with inappropriate medication use have received broad publicity in recent years. For example, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System drew attention to medical errors.3 It criticized the silence that too often surrounds the issue. Many members of the public were shocked to realize that the system in which they place so much trust was far from perfect.

Sometimes pharmacists have been implicated in medication errors. Technicians, too, have not escaped culpability.38–43 Several studies, most of which were performed in hospitals, have, however, demonstrated that appropriately trained and supervised pharmacy technicians can have a positive effect on equalizing the distributive workload, reducing medication errors, allowing more time for clinical pharmacy practice, and checking the work of other technical personnel.44,45 One study found that pharmacy technicians, when specially trained for the purpose, were as accurate as pharmacists in checking for dispensing errors.46 The United States Pharmacopeia Medication Errors Reporting Program (USPMERP) has noted the contributions that pharmacy technicians can make to medication error prevention through their involvement in inventory management (e.g., identifying problems relating to “look-alike” labeling and packaging).47 USPMERP also affirms that a “team approach” and “proactive attitudes” of pharmacists and technicians are important elements in reducing medication errors. The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention advocates that a series of checks be established to assess the accuracy of the dispensing process and that, whenever possible, an independent check by a second individual (not necessarily a pharmacist) should be made.48

Reports such as these call for an expanded role for pharmacy technicians in a much-needed, systematic approach to medication error prevention.

Preparing Pharmacy Technicians for Practice

Historical Overview. Originally, all pharmacy technicians received informal, on-the-job training. The majority of pharmacy technicians are probably still trained this way.8,18,49,50 Nevertheless, formal training programs, some of which are provided at the work site, are becoming more widespread. As state regulations, medications, record-keeping, and insurance requirements have become more complex, there has been a move toward more formal programs.51 Some employers have found that formal training improves staff retention and job satisfaction.18,52 Another advantage of a formal training program is that it can confer a sense of vocational identity. 49

Formal training programs for pharmacy technicians are not new; they were introduced in the armed forces in the early 1940s, and more structured programs were developed by the military in 1958. In the late 1960s, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare recommended the development of “pharmacist aide” curricula in junior colleges and other educational institutions.14 The first formal hospital-based technician training program was initiated around this time. Training programs proliferated in the 1970s as the profession sought to meet the need for a differentiated pharmacy work force.53 Many of these programs were established in response to requests from hospital pharmacy administrators; at that time there was little interest in formally trained technicians in community pharmacies who continued to train technicians on the job.54

In the 1980s, ASHP issued training guidelines intended to help hospital pharmacists develop their own training programs.7 ASHP recommended minimum entry requirements for trainees and a competency evaluation that included written, oral, and practical components. The guidelines were used not only by hospitals but by vocational schools and community colleges that wanted to develop certificate and associate degree programs.49

Acknowledging the importance of a common body of core knowledge and skills for all pharmacy technicians that would complement site-specific training, NACDS and NCPA developed a training manual, arranged into nine instructional sections and a reference section.55 Each section has learning objectives, self-assessment questions, and competency assessment for the supervising pharmacist to complete. The manual focuses on the practical, legal, and procedural aspects of dispensing prescriptions, sterile-product compounding, patient interaction, and reimbursement systems. APhA and ASHP also produce technician training manuals and resource materials for pharmacy technicians.56–60

To date, most programs have referred to the “training” rather than the “education” of pharmacy technicians. Further discussion of the need for clarification of the education and training needs of pharmacy technicians is provided below.

Academic Training Programs. In 2002, approximately 247 schools and training institutions in 42 states offered a range of credentials, including associate degrees, diplomas, and certificates, to pharmacy technicians. The military also continues to provide formal training programs for pharmacy technicians.

Formal technician training programs differ in many respects, one of which is length. The Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges of Technology School Directory lists 36 “pharmacy” programs.12 These programs vary in length from 540 to 2145 contact hours (24–87 weeks), with a median of 970 hours. ASHP, which accredits technician training programs, requires that programs have a minimum of 600 contact hours and a minimum duration of 15 weeks.61 The Pharmacy Technicians Educators Council (PTEC), an association representing pharmacy technician educators, supports the ASHP minimum requirements.62

The minimum acceptable length of the program is a matter of debate. Some pharmacy technician educators deplore a move within the education system to get people into the work force quickly. They believe that the pharmacy profession should make it clear that, while work force shortages and the needs of the marketplace are important considerations, rapid-training strategies do not seem appropriate for health care personnel whose activities directly affect the safe and effective use of medications.51 There should be a clear relationship between the nature and intensity of education, training, and the scope of practice.

Entrance requirements for training programs also vary. Some have expressed concern that a substantial number of trainees may lack the necessary basic skills and aptitude to perform the functions expected of technicians.51 The fact that about 30% of a certified pharmacy technician’s time is spent performing tasks that require mathematical calculations reinforces the importance of suitably qualified training applicants.21 ASHP acknowledged the need for minimum qualifications for training program applicants more than 20 years ago, but the issue continues to be a matter of debate.7

Progress Toward Standardization: The Model Curriculum. The absence of national training standards and the resultant variations in program content, length, and quality are barriers to the development of a strong technician work force. The problem is not unique to pharmacy technician training; other occupations in the health care sector also lack national standards. Nonetheless, it is ironic that persons in certain other occupations whose services have far less impact on public safety than do those of pharmacy technicians (e.g., barbers and cosmetologists) have training programs that, on average, are longer and less diverse than are pharmacy technician programs.63 Reflecting a common sentiment on this issue, a 1999 PTEC survey concluded that “Expansion of the role of pharmacy technicians must be in tandem with standardizing training and establishment of competencies. Increased responsibilities should be commensurate with increased education.”64 Likewise, there was a consensus at the Third PTCB Stakeholders’ Forum, held in June 2001, that national standards for pharmacy technician training are needed.65

Progress toward standardization has been facilitated by the Model Curriculum for Pharmacy Technician Training.66 Having taken the initiative and the leadership role, ASHP collaborated with several other pharmacy associations (APhA, the American Association of Pharmacy Technicians, PTEC, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy [first edition only], and NACDS [second edition only]) to develop the Model Curriculum. The first edition, released in 1996, was based on the findings of the 1992–94 Scope of Pharmacy Practice Project.67 Many of the revisions in the second edition, released in 2001, were based on a 1999 PTCB task analysis and accounted for changes in the scope of activities of today’s pharmacy technicians as well as changes expected to occur over the next five years.21,22 Significant changes were made, for example, in sections dealing with the technician’s role in enhancing safe medication use, assisting with immunizations, and using “tech–check–tech” (a system in which pharmacy technicians are responsible for checking the work of other technicians with minimal pharmacist oversight).

The organizations that developed the model curriculum do not expect that every training program will cover every goal and objective of the curriculum; rather, the curriculum should be seen as a “menu” of possible learning outcomes. The model curriculum provides a starting point for identifying core competencies for pharmacy technicians.22 It acknowledges the need for a level of understanding of basic therapeutics, anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology. The curriculum does not include recommendations regarding the relative amount of time that should be allotted to each module, but such guidelines are under consideration.68

The Future Preparation of Pharmacy Technicians: Education Versus Training. Virtually all the consensus-development meetings and studies that have investigated training requirements for pharmacy technicians have called for the development of standardized training in some form.51,69 APhA and ASHP concur with this position.2,70,71

Such a recommendation would best be accompanied by two important caveats. The first is that any national standards for education and training of pharmacy technicians will not eliminate the need for additional, site-specific training that focuses on local policies and procedures.52,65 Second, standards-based education or training can conceivably be delivered successfully in a variety of different settings.

However, what exactly is meant when the terms education and training are applied to pharmacy technicians? They have tended in the past to be used somewhat interchangeably. However, a distinction needs to be made and a balance between the two needs to be reached to ensure that pharmacy technicians are adequately and appropriately prepared to perform, in a safe and efficient manner, the functions and responsibilities that are assigned to them—both now and in the future. As has already been noted in this paper, the roles and responsibilities of pharmacy technicians have evolved and expanded in recent years. While, in the main, pharmacy technicians perform routine tasks that do not require the professional judgment of a pharmacist, state pharmacy practice acts now recognize that pharmacy technicians are being assigned new and different functions in the practice setting, some of which may require a higher level of judgment or extensive product knowledge and understanding.

Training involves learning through specialized instruction, repetition and practice of a task or series of tasks until proficiency is achieved. Education, on the other hand, involves a deeper understanding of a subject, based on explanation and reasoning, through systematic instruction and teaching. People may be proficient in performing a task without knowing why they are doing it, why it is important, or the logic behind the steps being performed. While education (as described above) may involve a training component, both are vital to the learning (or preparation) of the technician. Barrow and Milburn72 give a useful treatise on this subject. The education and training of pharmacy technicians and other supportive personnel must be commensurate with the roles they are performing. To ensure quality, both the education and training components should be standards based.

Accreditation of Pharmacy Technician Education and Training

The Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy (CCP) defines accreditation as “the process by which a private association, organization, or government agency, after initial and periodic evaluations, grants recognition to an organization that has met certain established criteria.”73 Accreditation is an integral aspect of ensuring a quality educational experience.

For pharmacy technician education and training, there are two types of accreditation: programmatic (also referred to as specialized) and institutional. Programmatic accreditation focuses specifically on an individual program, whereas institutional accreditation evaluates the educational institution as a whole, with less specific attention paid to the standards of individual programs offered by the institution. Institutional accreditors operate either on a regional or national basis; the latter usually has a more focused area of interest. A system of dual accreditation, in which institutional accreditation is conducted by regional accrediting bodies and programmatic accreditation is conducted by the American Council on Pharmaceutical Education (ACPE), has worked well for schools and colleges of pharmacy since the 1930s.

Based on information obtained from published directories, it is estimated that only 43% of the 247 schools and training institutions referred to earlier are accredited by bodies specializing in technical, allied health, and paraprofessional education; 36% have their programs accredited by ASHP; and 12% are accredited by both ASHP and one or more of the institutional accrediting bodies specializing in technical, allied health, and paraprofessional education.

Institutional Accreditation. For institutions offering pharmacy technician training, national institutional accreditation is carried out by at least four agencies: the Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges of Technology (ACCSCT), the Accrediting Bureau of Health Education Schools (ABHES), the Council on Occupational Education (COE), and the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools (ACICS). All of these agencies are recognized by the U.S. Department of Education. None has a formal national affiliation with the profession of pharmacy.

Because there are no nationally adopted standards for pharmacy technician training, it is difficult for institutional accrediting bodies to set detailed program requirements. ACCSCT standards require programs to have an advisory committee, the majority of whose members represent employers in the field of training.74 ABHES has a suggested curriculum outline for pharmacy technician programs. In an effort to improve the quality of their programs, COE and ABHES plan to switch from institutional to program accreditation.75 Of some concern is the fact that such accreditation systems (for pharmacy technician training programs) would be outside the pharmacy profession and would not be based on national standards recognized by the profession.

Program Accreditation. Program accreditation for technician training is offered by ASHP. ASHP accreditation of technician training programs began in 1982 at the request of hospital pharmacists. Many hospital-based technician training programs were already using ASHP’s guidelines and standards, but they expressed a need for a more formal method of oversight to ensure the quality of training. ASHP had already accredited pharmacy residency programs and moving into technician accreditation seemed a logical step.

Initially, nearly all ASHP-accredited programs were hospital based. This is no longer the case; of the 90 technician training programs currently accredited by ASHP, only 3 are hospital based. Over 90% of programs are located at vocational, technical, or community colleges.76

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree