LEARNING OBJECTIVES

To describe the nature and frequency of professionalism lapses.

To explain the impact of unprofessional behavior on patients, students, and the healthcare team.

To identify why professionalism lapses occur.

To illustrate how most individuals who witness lapses respond to them.

To outline strategies to respond to a spectrum of professionalism lapses.

INTRODUCTION

In today’s complex and often chaotic environment, physicians are often challenged as they strive to live their professional values. Physicians may struggleto maintain their equanimity in the face of suffering and dying patients, heightened productivity demands, work-related fatigue, and distressed colleagues. As humans, we may also be dealing with struggles outside of work. Physicians are not immune to personal illness, relationship troubles, or distractions related to dependent children or parents.Rather than be surprised that lapses in professionalism occur, we should anticipate that they will occur and prepare to handle them in a way that honors the trust that society places in both individual physicians and the collective profession when they grant us the privilege of self-regulation.

Unfortunately, individually or collectively we do not always live up to this commitment. Highly publicized incidents of physicians as the perpetrators of crimes against society, ranging from financial fraud to sexual assault to even more egregious crimes are rare. When they occur, however, they raise questions about how the medical profession could have let someone with this flawed character enter or remain within the profession (Stewart, 2000). More common are examples of ethical transgressions, such as research- or practice-based conflicts of interest, where physicians have placed their financial or career success ahead of the best interests of their patients (Brownlee, 2008). Even more common are the type of professionalism lapses that don’t make headlines, but that pervasively undermine the culture of respect that is essential to the effective functioning of our patient care and educational environments (Leape et al, 2012a; Walrath, Dang, & Nybert, 2013; Wear et al, 2009; Hickson et al, 2007; Samenow et al, 2013; Silverman et al, 2012). These include the daily incivilities that occur in the workplace and are characterized by disrespectful language, dysfunctional relationships, disregard of policies and procedures, and dismissive or destructive responses to clinical disagreement or uncertainty. Figure 11-1 describes these different types of breaches of professionalism.

WHAT DO PROFESSIONALISM LAPSES LOOK LIKE AND HOW COMMONLY DO THEY OCCUR?

Because unprofessional behavior covers a spectrum of actions that range from lapses to transgressions to crimes, it is difficult to pinpoint the frequency of professionalism lapses. The literature relevant to understanding these lapses can be found not only in articles that specifically address professionalism (Hickson et al, 2007; Teherani et al, 2005; Adams, Emmons, & Romm, 2008; Campbell et al, 2007; Buchanan et al, 2012; Humphrey et al, 2007; Arnold, 2006; Brater, 2007; Brainard & Brislen, 2007; Papadakis et al, 2005; Wasserstein, Brennan, & Rubenstein, 2007), but also in articles about the hidden curriculum (Hafferty, 1998; Testerman et al, 1996; Billings, 2011), moral distress (Wiggleton et al, 2010), disruptive people and behaviors (Walrath, Dang, & Nybert, 2013; Samenow et al, 2013; Silverman et al, 2012; Saxton, Heinz, & Enriquez, 2009; Reynolds, 2012; Leape et al, 2012a; McLaren, Lord, & Murray, 2011; Williams & Williams, 2008; Rosenstein & O’Daniel, 2008; Rosenstein & Naylor, 2012; Pronovost et al, 2003), problem residents (Wear et al, 2009; Adams, Emmons, & Romm, 2008; Brenner et al, 2010; Dupras et al, 2012; Sanfey et al, 2012; Zbieranowski et al, 2013), burnout (Billings etal, 2011; Dyrbye & Shanafelt, 2011; Dyrbye et al, 2010), and impaired physicians (Campbell et al, 2007) (Table 11-1).

| Construct | Definition | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Disruptive behavior | “Personal conduct, whether verbal or physical, that negatively affects or that potentially may negatively affect patient care” (Samenow etal, 2013). | Disruptive behaviors are unprofessional. When demonstrated by valued role models in the clinical environment, they create the hidden curriculum. |

| Hidden curriculum | Lessons learned that were not explicitly intended and that may be counter to the formal curriculum (Hafferty, 1998). | The hidden curriculum is often more powerful than the explicit curriculum because it is provided by role models who are successful in a role to which the students aspire. |

| Moral distress | Moral distress results when one knows the morally correctresponse to the situation but cannot act because of institutional or hierarchical constraints (Wiggleton et al, 2010). | As learners develop a professional identity based on classroom and workplace learning experiences, they may experience moral distress if they feel they are unable to act in the “right” way because of institutional barriers. |

| Burnout | Burnout is characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of personal accomplishment. | Moral distress and cynicism that comes from unresolved moral quandaries can contribute to burnout and further cynicism, depersonalization and more disruptive behaviors. |

| Impaired physicians | The Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) defines impairment as the inability of a licensee to practice medicine with reasonable skill and safety as result of a mental disorder, physical illness or condition or substance abuse (FSMB, 2011). | Illness does not equate to impairment. Impairment refers to the inability of the physician with the illness to meet standards. |

Over the last decade, the profession’s definition of what behaviors are unprofessional and disruptive has expanded. In the last century, a physician’s professionalism was judged largely by how they interacted with patients, without regard to how they treated others in the healthcare environment. Comments like, “He is a fantastic doctor, just not very nice to the nurses,” illustrated this belief. Previously unprofessional behaviors were viewed as limited to overt acts of verbal abuse and intimidation (yelling at or threatening the job or wellbeing of another healthcare professional) or physical violence (throwing a scalpel in the operating room). Presently, we hold a broader view of disruptive behaviors to include patterns of behavior that are passive-aggressive, including refusal to comply with evidence-based safety protocols or pathways, condescending or sarcastic responses to inquiries, failure to answer pages or complete documentation, hostile avoidance of or refusal to engage in collegial dialogue, disrespectful comments about patients or other professionals, and inappropriate humor (see Table 11-2) (Walrath, Dang, & Nyberg, 2013; Saxton, Hines, & Enriquez, 2009; Reynolds, 2012; Leape et al, 2012a).

| Threatening | Passive-aggressive | |

|---|---|---|

| Behavior that directly impacts patients |

|

|

| Behavior that directly impacts other healthcare professionals and indirectly impacts patients |

|

|

HOW COMMON IS UNPROFESSIONAL BEHAVIOR?

The percentage of physicians who exhibit behavior that is either sufficiently egregious or that persists enough to warrant intervention by an authoritative figure is fortunately small, estimated to be approximately 3% to 5% in any given institution (Hickson et al, 2007; Leape & Fromson, 2006). However, nearly everyone in the healthcare environment has had contact with or witnessed a physician who exhibited behavior they describe as unprofessional or disruptive at some time. More than 95% of physician executives attest that they are aware of problem physicians within their medical centers (Weber, 2004). The majority of nurses and physicians in operating rooms, emergency departments, and obstetrical units report incidences of unprofessional behavior (Rosenstein & Naylor, 2012; Saxton, 2012). More than 90% of pediatric nurses reported witnessing at least one disruptive behavior in the preceding 90 days (Saxton, 2012). In one survey of 102 hospitals, nurses were more likely to report witnessing disruptive behavior than were physicians, with 88% of nurses describing these behaviors in physicians and only 51% of physicians noting disruptive behavior in other doctors (Rosenstein & O’Daniel, 2008). These data raise questions about whether nurses and physicians agree on what constitutes disruptive behavior.

Residents and medical students observe, and also admit to, participating in unprofessional behavior including cheating, falsifying patient records, and engaging in disrespectful comments or humor about others. Between one fourth and one half of residents surveyed described witnessing multiple incidents (> 4 times) of disrespect of patients, residents, students, and nurses by other residents (Billings et al, 2011). Nearly all students responding to surveys describe witnessing unprofessional behavior on thepart of faculty, residents, and peers (Wiggleton et al, 2010). Students themselves are the subjects of unprofessional behavior. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) monitors student mistreatment as a component of its Graduation Questionnaire (GQ), administered annually to all graduating medical students. In 2012, 33% of respondents reported that they had experienced public humiliation at least once in their medical school tenure and 15% noted that they had been subject to sexist remarks (Mann, 2012). Articles that describe specific anecdotes are profoundly disturbing (Brainard & Brislen, 2007).

WHAT IS THE IMPACT OF UNPROFESSIONAL BEHAVIOR?

Jeanette Smith-Johnson, a hospital pharmacist, was really upset. She had just received an order for an antibiotic dose that was too high, given the patient’s age and renal function. When she went to the floor to talk with the prescribing resident, Dr. Estania chewed her out in the middle of the patient care unit, within earshot of multiple doctors, nurses, and patient families. Then Dr. Estania turned to her team and said, “All pharmacists are people who failed to get into medical school.” Jeanette felt that it was too risky to say anything about the incident but it made her feel like the talk about interprofessional team work inthe institution was just “lip service.”

Physicians and nurses who display disruptive and unprofessional behaviors such as disrespectful comments, intimidation, harassment, physical threats, or violence negatively affect the culture of collaboration and respect that is so critical to the delivery of safe, high-quality care. Nurses, trainees, and students may hesitate to contact an attending physician about a change in a patient’s status if they fear they will be subjected to verbal abuse. Members of an operating room team or intensive care unit may be reluctant to point out a break in sterile technique if they feel they may be the target of physical violence. These unacceptable behaviors are unfortunately common. In a study of personnel in more than 100 hospitals, almost three fourths of those responding felt that the presence of disruptive behavior contributed to poor quality and adverse events. Eighteen percent stated that they were aware of a disruptive event that directly compromised quality of care (Rosenstein & O’Daniel, 2008). Intimidation of a nurse or pharmacist was the cause of 7% of medication errors in one hospital (Smetzer et al, 2005). Given our understanding of how critical attention to detail is in today’s dynamic medical environments, it is particularly worrisome that more than two thirds of nurses subjected to verbal abuse in pediatrics and perioperative units described a transient decrease in their concentration or ability to engage in critical thinking as a consequence of the abuse (Saxton, 2012). Physicians who engage in disruptive or unprofessional behavior are bad for business as well. Verbal abuse on the part of physicians or other nurses toward nurses is described a significant cause of nursing turnover (Rosenstein, 2011). Physicians who refuse to comply with standards for documentation and billing also threaten the economic viability of their organization.

Dr. Stevens is a tenured faculty member in critical care who is on call for the intensive care unit (ICU). He is contacted by one of the senior surgical residents, Dr. Hussain, and asked to accept a transfer from one of the general surgical services. The patient in question was admitted today for revision of a dialysis shunt but had an episode of hypotension that was prolonged and took a long time to respond to treatment. Dr. Hussain felt that the patient needed intensive care. The faculty member refused to accept the patient and directed the resident to admit the patient to the regular ward, stating that he didn’t have room on his service for every dying dialysis patient.

In the scenario above, Dr. Hussain is left feeling abandoned as he feels that his patient needs ICU monitoring but the staff physician is unwilling because of his views about dialysis patients. Dr. Hussain is in a difficult position that caused him moral distress and feelings of helplessness. In a study conducted at Vanderbilt University Medical School, students consistently described a greater degrees of moral distress when witnessing situations in which they felt that patients did not receive appropriate care than those in which members of their team made disrespectful comments about other services or patients who were not present (Wiggleton et al, 2010). Table 11-3 presents examples of situations that cause moral distress for students. It is notable that students sometimes witness disrespectful behavior directed at other physicians or services but do not find it particularly distressing, raising the possibility that they have accepted this type of behavior as normative.

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Situations Involving Patient Care | A patient presented with advanced disease because they had faced barriers to access to care. |

| Optimal care was not provided to a patient because of insurance status. | |

| Poor communication between teams negatively impacted patient care. | |

| The team continued to provide aggressive care at the urging of patients or their family even when no potential benefit was evident. | |

| I felt that a patient was discriminated against by a member of my team. | |

| The attending physician or resident answered a patient’s questions inadequately or simply ignored them. | |

| Our team withdrew care at the patient’s or family’s request, although I thought the patient could have survived with further treatment. | |

| A member of our team was rude or disrespectful to a patient or family member. | |

| Situations Involving Self | One of my superiors behaved inappropriately but I did not report it, out of fear it would negatively impact my grade or because I felt pressured by the attending or resident. |

| A member of my team was disrespectful to someone below him or herself in the team hierarchy. | |

| I performed a procedure that I did not feel qualified to do because I was afraid of being viewed as incompetent. | |

Michael is a 3rd-year medical student. All students have been assigned to meet monthly with an elderly citizen as part of a program to introduce students to healthy elderly. After each monthly visit, the student is required to file a brief report. At the end of the winter quarter, Michael is doing surgery and submits his final report on his senior partner during the last week of the surgical clerkship. On the day following his report submission, his senior partner contacts the medical school to ask why he hasn’t seen Michael for the past 2 months.

Uncorrected unprofessional behavior may have negative consequences for the individual as well. If Michael never gets feedback or does not correct these behaviors, he may be at risk of future difficulties. Studies consistently find a correlation between poor physician communication, patient dissatisfaction, and malpractice suits (Hickson et al, 2002). Students who were the recipient of more than one complaint about professional irresponsibility were 8.5 times as likely as their peers to be subjected to medical board sanctions in their subsequent career. In addition, students who demonstrated diminished capacity for self-improvement were 3.1 times as likely to be sanctioned (Papadakis et al, 2005). The presence of any negative descriptors about behavior in an individual’s Medical Student Performance Evaluation showed a strong correlation with poor performance during residency (Brenner et al, 2010). In the case of Michael, the lapse needs to be dealt with even though the course is over.

LEARNING EXERCISE 11-1

Have you ever heard a colleague or trainee make a joke about a patient and his medical condition?

How did you feel?

Did you laugh with others? Did you say anything to the individual who made the joke? If so, what did you say? When did you say it?

If not, why didn’t you? Were you planning on talking about it later, in private? If so, did later ever come?

WHY DOES UNPROFESSIONAL BEHAVIOR OCCUR?

Rafael was uncomfortable. His fellow intern, Delilah, was one of the smartest people in their residency group and he had been looking forward to working with her this month at the county hospital. They had a huge service of very sick patients, and overall they were providing very good care to them. But almost every day, Delilah made sarcastic or demeaning comments about patients—the hopeless guy with alcoholism, the woman who likes to turn tricks, and so on. Instead of anyone saying something about the importance of treating patients with respect, the rest of the team just laughed or ignored the comments. Rafael wasn’t sure what he should do—perhaps he was overly sensitive. After all, what was important was what happened in the patient’s room, not in the hallway, wasn’t it?

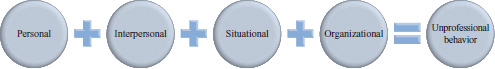

Given that all physicians enter medicine to serve others, it is hard to understand why any physician or physician-in-training would engage in behaviors that interfere with their doctor-patient relationships, or with the effective delivery of high-quality healthcare. It is tempting to believe that if we simply sought out and removed the perpetrators of unprofessional behavior from the profession, the problem would be solved. This is certainly true for those who engage in truly egregious behavior and for those who, despite counseling, are unable to change the ways in which they are behaving. However, as we have discussed in other chapters, unprofessional behavior is often caused by good physicians and physicians-in-training who temporarily lack the knowledge skills or attitudes to manage the professionalism challenge in front of them (see Chapter 2, Resilience in Facing Professionalism Challenges, and Chapter4, Fostering Patient-Centered Care). Some may also lapse because they have adopted a style of behavior that they fail to realize is unprofessional. In our modification of the Johns Hopkins Model for Disruptive Clinician Behavior (Walrath, Dang, & Nyberg, 2013) triggers for unprofessional behavior include personal issues, interpersonal issues, situational factors and organizational policies, procedures, and culture (Figure 11-2).

Examples in each of the categories listed earlier are presented in Table 11-4. Although any given healthcare provider may be able to manage a single issue without lapsing into unprofessional behavior, the presence of multiple issues may overwhelm the capacity of a given clinician to sustain their commitment to professionalism. Particularly vulnerable are physicians-in-training, who may lack the experience to recognize and respond to triggers before they lapse.

| Type of stressor | Examples of stressors |

|---|---|

| Personal |

|

| Interpersonal |

|

| Situational |

|

| Organizational |

|

When educational and clinical leaders witness or hear reports about unprofessional behavior in the physicians for whom they are responsible, they may wonder if the person has a psychiatric illness or a substance abuse problem. Estimates vary about the extent to which professionalism problems are caused by unrecognized, unmanaged, or untreatable illness. Burnout appears to be a risk factor for unprofessional behavior that is modifiable if recognized (Dyrbye & Shanafelt, 2011; Dyrbye et al, 2010). In physicians whose behavior is sufficiently problematic to warrant formal evaluation, psychiatric disorders may be common (Williams, Williams, & Speicher, 2004). Psychiatric disorders identified include Axis I disorders such as depression, anxiety, bipolar illness, substance use, and dementia and Axis II disorders such as personality disorders (paranoid, narcissistic, passive aggressive, and borderline disorders) (Reynolds, 2012; Williams & Williams, 2008). Psychiatric disorders do not excuse unprofessional behavior, but their presence demands a comprehensive approach to preventing future lapses, involving medical therapy, counseling, and behavioral change.

HOW DO PEOPLE USUALLY RESPOND TO A WITNESSED PROFESSIONALISM LAPSE?

Dr. Sundera is a PGY-1 resident in surgery at a hospital different from where she had gone to medical school. She is appalled at the amount of joking that goes on in the operating room—mostly directed at the anesthetized patient but some at the medical students. All of the residents and the anesthesiology attending just laugh when they hear these comments. Was this the way her entire residency experience was going to play out?

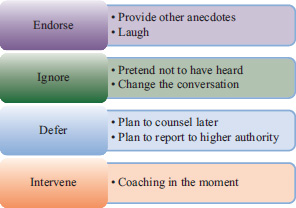

When we observe a colleague or trainees behaving in ways that makes us feel uncomfortable we typically, and usually instinctively, respond in one of four ways: endorse, ignore, defer action or intervene to stop it (Figure 11-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree