LEARNING OBJECTIVES

To understand the rationale for physicians to address the stewardship of finite resources.

To understand the dilemma physicians experience in caring for individual patients and simultaneously considering the use of resources.

To learn specific communication skills for conducting conversations with patients about unnecessary tests or treatments.

To learn the roles of teams, healthcare systems, and professional organizations in stewardship of finite resources.

INTRODUCTION

Donna Johnson is a 40-year-old woman who is the CEO of a small manufacturing company. Her job is stressful and she has a long history of headaches, but recently she feels the headaches are increasingly frequent despite her efforts to manage them with stress reduction. She has a neighbor who recently was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor who also had headaches, and she is asking her family doctor, Dr. Hernandez, to order a computerized tomography (CT) scan to be sure she does not have a tumor.

Dr. Hernandez takes a detailed history and rules out any other neurologic symptoms. Her complete physical examination, including a careful neurologic examination, is all normal. Dr. Hernandez concludes that these are tension headaches and discusses this with the patient. Ms. Johnson would like a CT scan just to be 100% sure, but Dr. Hernandez does not think it is clinically indicated. Furthermore, the test is expensive, even though the patient has insurance that would cover it. Dr. Hernandez thinks to herself that it is just easier to order the test than try to explain the risks and benefits to a worried patient.

Every day physicians make many decisions about whether to order, or not to order, laboratory tests and imaging procedures. This scenario and similar scenarios are very common in daily practice. Patients with symptoms are worried and want their physicians to use the best of medical science to quickly diagnose and treat a problem or to reassure them that nothing serious is wrong. Some believe that tests and x-rays are perfectly accurate and humans are not, so they equate an order for a test as better care than a careful clinical examination. Consumer advertising and Internet sites recommending non–evidence-based tests and treatments reinforce these beliefs.

Physicians worry as well. Test ordering can be driven by a physician’s concern that they might miss an important diagnosis and cause their patient unnecessary suffering. Worry that declining to order an unnecessary test might negatively affect their patient’s satisfaction may also prompt decisions to obtain tests that are not truly indicated. Belief that test ordering represents the standard of care and thus is a defense against malpractice claims also drives this behavior. It is safe to say that we have a “more is better” view of medical testing, even when we know that these tests do not add value to patients’ care and when these tests may even have some risks for patients. Even more concerning is the reality that current strategies in healthcare financing often make it more lucrative for some physicians, and the institutions that employ them, to order tests of marginal or no benefit than to guard against this approach.

Stewardship of valuable resources is a complex topic in professionalism. It is clearly unprofessional to order tests that are unnecessary simply because the physician will earn more money if they do so and probably unprofessional to routinely order tests as a strategy to protect against personal injury from a malpractice claim. Yet, ordering tests of marginal or no benefit to allay concerns, avoid missed diagnoses, and comply with patient requests (or demands) may seem compatible with professionalism values of prudence, and respect for patient autonomy. However, ordering unnecessary tests and treatments that are unlikely to yield benefits and may cause physical harm to patients (such as radiation exposure or antibiotic-associated diarrhea) or adverse financial consequences for patients (such as out-of-pocket expenses) is counter to the professionalism values of excellence and nonmaleficence. In addition, spending valuable national resources on unnecessary tests and treatment, leaving less money for improving quality, increasing access for the underserved, and targeting complex problems of the social determinants of health is contrary to our professional commitment to social justice.

In this chapter, we tackle the complex professionalism decisions that physicians need to make in their day-to-day work with patients. We discuss the rationale for physicians to care about the use of finite resources. We use the professionalism framework to illustrate behaviors that can be demonstrated by individual physicians, the healthcare team, the healthcare setting, and professional organizations in order to manage limited resources wisely.

WHY SHOULD WE CARE ABOUT HEALTHCARE SPENDING?

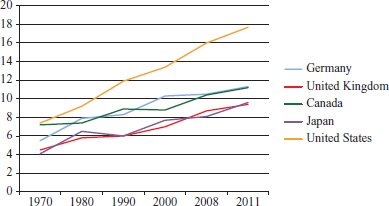

The problem of the rising and unsustainable cost of healthcare is a pressing issue in all developed countries. The total healthcare expenditure as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) has been rising in many countries over the last decades; the United States spent 7.4% of GDP on health in 1970, 11.9% in 1990, and 16.0% in 2008. Estimates are that this will rise to 20% by 2020 (Keehan et al, 2011; Shatto & Clemens, 2011)—a figure that is unacceptable if society hopes to have resources for other social goods including education, environmental issues, and public safety. Part of this relentless increase in expenditures is a consequence of the tremendous biomedical advances of the last century; the availability of new diagnostic and therapeutic options has increased the number of people who live longer. However, some of the drivers of healthcare expenditures relate to the administrative complexity and fragmentation of care that characterize our healthcare system. Countries with more coordinated care, better primary care services, and financial mechanisms to control cost (Figure 7-1) spend a lower percentage of GDP on healthcare than the United States does. For example, in 2008 Canada spent 10.4% of GNP on healthcare and the United Kingdom spent 8.7%, compared to 16% in the United States.

What makes this high spending in the United States even more unacceptable is that health outcomes are not better but actually worse than in the countries that spend less. Measures used to assess quality of care by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) include infant mortality rates, life expectancy at birth, life expectancy at age 65 years, and mortality amenable to healthcare (a measure intended to assess the functioning of the healthcare system). On many of these measures the United States performs least well (Table 7-1). For example, infant mortality rates are 6.7 per 1000 live births in the United States, compared to 5.1 in Canada and 3.5 in Germany in 2008. Life expectancy for a man is 3 years lower in the United States compared to Canada. Simply stated, we spend more, but do not have better outcomes for the population.

| Infant mortality, Per 1000 live birthsa | Life expectancy at birth (years)a | Life expectancy at age 65 (years)a | Mortality amendable to healthcare, 2002-3, deaths per 100,000 populationb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||

| Germany | 3.6 | 78.4 | 83.2 | 18.2 | 21.2 | 90 |

| United Kingdom | 4.7 | 79.1 | 83.1 | 18.6 | 21.2 | 103 |

| Canada | 4.9 | 78.7 | 83.3 | 18.5 | 21.6 | 77 |

| Japan | 2.3 | 79.4 | 85.9 | 18.7 | 23.7 | 71 |

| United States | 6.1 | 76.3 | 81.1 | 17.8 | 20.4 | 110 |

Despite the high expenditures on healthcare in the United States, many Americans do not have access to medical care. Surveys demonstrate that approximately 25% of Americans did not get a prescribed medication, test, or treatment due to their lack of ability to pay for it. In 2009, 51 million Americans were lacking any form of health insurance (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010, page 22); a number that has been steadily rising over the last three decades. Poorer Americans are less likely to have health insurance than wealthy Americans. In addition, 62% of all people filing for personal bankruptcy cite high healthcare costs and 25% of citizens over 65 who file for bankruptcy identify out-of-pocket healthcare expenses as a major cause for their financial problems, despite the fact that they are enrolled in Medicare (Bodenheimer & Grumbach, 2012).

Of great concern is the observation that much of the vast amount of money poured into the U.S. healthcare system is not well spent and does not add value to care. Studies estimate that 30% of our healthcare expenditures can be attributed to waste; duplicative, non–evidenced-based or harmful tests or treatments (Berwick & Hackbarth, 2012). The aphorism that the most expensive medical device is the physician’s pen (or keyboard in today’s environment) is true: 80% of all healthcare expenditures are driven by physician decisions. Economists estimate that if we could increase the value of our healthcare expenditures to rival our world peers, our expenses would go down by 15% to 30% and we could use those dollars to achieve better healthcare and better social conditions for all.

One way of dealing with rising healthcare costs would be to have payers and regulators simply cut reimbursement rates and deny expenditures. This approach, initiated by stakeholders outside of the profession, could result in rationing by denying people needed care. Instead, ethicists and physician leaders have suggested that the profession should solve the problem of high costs and low values, using the values of professionalism. Instead of worrying about rationing, we should be focusing on reducing waste—eliminating care that does not confer a benefit and, in some circumstances, may result in harm. Diverting the dollars spent on waste to improving our society’s access to care that is reliably safe, effective, and high quality is an aspirational goal that should be motivating to all physicians.

IS STEWARDSHIP OF VALUABLE RESOURCES A WAYOF JUSTIFYING RATIONING AT THE BEDSIDE?

Dr. Green is a 3rd-year internal medicine resident. At morning rounds, he presents a case of an 83-year old patient admitted the previous night with a recurrent episode of congestive heart failure due to ischemic cardiomyopathy. Dr. Green presents the details of the history, physical examination, and the results of initial investigations, including cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The attending cardiologist inquires about why Dr. Green ordered the MRI and whether it was helpful to the care.

Training shapes professional practice patterns. Studies show that physicians who are trained in high-quality environments learn patterns of care that influence their future practice in positive ways. For example, Asch and colleagues (2009) found that the obstetrical training program where a physician trained was associated with the physician’s maternal complication rates in practice. Women treated by obstetricians trained in residency programs in the bottom quintile for risk-standardized major maternal complication rates had an adjusted complication rate of 13.6%, approximately one third higher than the 10.3% adjusted rate for women treated by obstetricians from programs in the top quintile. The Dartmouth Atlas, which describes variations in the quality of care between hospitals, has recently published a report entitled, “What kind of physician will you be? Variation in healthcare and its importance for residency training” (Arora & True, 2012). This report emphasizes that residents shape their ideas about what it means to be a good physician by emulating the behavior of the supervising attending physicians and by responding to cues in the environment. Dr. Green’s decision to order an MRI may be prompted by a specific diagnostic question (perhaps there were findings suspicious of amyloidosis on the patient’s exam). Alternatively, he may be ordering the test because her prior attending physicians included it in their “usual” workup of cardiomyopathy patients and did not convey to him what constituted a “usual” case that justified the MRI. Hospital reimbursement may favor rapid discharge of patients, and hence residents are counseled to pay attention to length of stay. Dr. Green may believe that ordering the test now, before he discusses the case with the attending physician, may shorten the patient’s time in the hospital. He may also be ordering the MRI because he is interested in learning more about cardiac MRI and doesn’t realize the cost that the patient will bear because of his curiosity. In fact, the reason the indirect medical education component of Medicare payment to hospitals exists is because of the assumption that care provided by residents includes some waste in the form of excess tests and treatment delays. In short, the culture in many medical training programs encourages trainees to order unnecessary tests, and the patterns learned in residency training may influence future practice of physicians.

IF PROFESSIONALISM INCLUDES STEWARDSHIP OF VALUABLE RESOURCES, WHY IS THE TOPIC SO RARELY DISCUSSED IN EDUCATION AND IN PRACTICE?

One simple answer is that the actual costs of care are often hidden from the view of the physicians and their patients. Even less transparent is how much a specific patient will be charged for care, what part of that charge their insurer will pay, and how much they will personally be required to pay. Some experts in cost-conscious care have urged physicians to manage this problem of cost confusion by taking the approach of “universal financial precautions.” Modeled on the same principles as universal precautions for blood-borne illness, universal financial precautions urge physicians to assume that each patient in front of them is one major diagnostic test away from bankruptcy. A recent randomized trial demonstrated that physicians who saw the cost of tests as they ordered them (with no other intervention) decreased their ordering resulting in a 10% saving (Feldman et al, 2013).

More difficult to navigate is the perceived conflict between the professionalism values of patient welfare and social justice. Some physicians believe that even a negative test provides useful information, and that discussions of cost in the care of individual patients is contrary to the primacy of patient welfare. They argue that considering social justice while caring for an individual patient may be construed as rationing at the bedside. A resolution of this perceived conflict between patient-centered professionalism values and society-centered professionalism values can be achieved, if one considers the reality of diagnostic testing and treatment decisions. Commitment to care for the individual patient can be fulfilled if the physician is equally concerned with avoiding errors of commission (those that result from ordering diagnostic tests or treatments of questionable value) and simultaneously errors of omission (those that result from not ordering indicated tests and treatments). The decision to order only evidence-based tests and treatments protects patients from the harm that may result when false-positive results lead to additional, often more invasive, tests (e.g., when cumulative radiation exposure increases the risk of cancer; and when seemingly benign antibiotics and corticosteroids cause rare, but disabling complications).

Some physicians also express concern about patient autonomy, as many patients may wish us to order certain tests and request that we do so. Ethicists tell us that, in contrast to liberty, autonomy is not absolute. Autonomy must be exercised with information and understanding. Supporting the principle of respect for patient autonomy means that the physician educates, informs, and counsels patients about the evidence-based choices available to them. It does not mean complying with patient demands for non–evidenced-based care. With these frames, the physician can maintain patient-centered professionalism, while they address their society-centered commitments to steward valuable resources.

In fact, we believe that we are at a time of a significant shift from a prior culture of caring for just one patient to a newer view of concurrent broader societal perspective. Below, we discuss the roles that each part of the system—individual patient and physician, the team, the healthcare setting, and professional organizations—can play in shepherding finite resources to provide the highest quality of care for the greatest number of patients. We also provide specific strategies for conducting conversations with patients about the choice of ordering (or not ordering) tests and procedures.

LEARNING EXERCISE 7-1

Think of a recent time when a patient asked you to order a test that you thought was not indicated medically.

What were your thoughts about ordering or not ordering the test?

What factors did you consider? Were there factors favoring and opposing ordering the test?

Did you discuss the issues with the patient? Was the outcome of that conversation satisfactory?

PHYSICIAN–PATIENT INTERACTION

John King is a 36-year-old man who works as a contractor. He comes in to see his family doctor with a 1-week history of low back pain, which is interfering with his ability to work; in fact, he has missed 5 days from work. The pain started after Mr. King lifted a heavy pail and twisted his back. He is frustrated because he does not get paid if he is not at work, but he is very uncomfortable, especially when he bends forward. The pain is disturbing his sleep; he wakes when he rolls over in bed. He has no radiation of the pain into his legs. He has not had any change in his bowel or bladder function. He requests a CT of his back so that he can “figure out the problem and get back to work sooner.”

Dr. Deyo examines Mr. King and finds no evidence of any neurologic signs in his legs. He is aware of the literature indicating that imaging is not indicated in the absence of neurologic symptoms or signs, particularly with a short (less than 6-week) history of pain. Although he knows that the CT is not indicated, he also knows from experience that it takes time to explain the reason the test is not indicated and sometimes patients leave his office unhappy when they didn’t get the test they requested. He is already behind in his schedule and the office staff has encouraged him to hurry up if he can.

This is a very common situation for practicing physicians in all specialties. Patients request treatments and tests that are not indicated—antibiotics for an upper respiratory tract infection, stress electrocardiography to check for coronary disease, and so on. Dr. Deyo’s reflection on this situation is also common: Is it worth the effort to explain the rationale for not ordering the test? Is it just more expedient to order the CT despite the lack of necessity? He knows the conversation will take some time and that not all patients accept the explanation. Furthermore, Dr. Deyo may think that if he does not order the test now, the patient will just go to another doctor to get the CT, making the whole exercise futile. Even worse, they might complain about him on a public Web site, like Angie’s List or Yelp, and that may make other patient’s doubt his competency and compassion (Ginsburg, Bernabeo, & Holmboe, 2013; Ginsburg et al, 2012).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree