LEARNING OBJECTIVES

To define integrity and accountability as they relate to the practice of medicine.

To describe the importance of integrity and accountability as core elements of the social contract between the profession and society.

To outline behaviors that demonstrate integrity and accountability.

To describe the contribution of the team and the system to integrity and accountability.

INTRODUCTION

Dr. Porter was suddenly struck by an awful thought—he realized he had made a mistake on a prescription he wrote for a patient in the emergency department. It was toward the end of a very busy shift and one of the last patients he saw had a clear-cut case of cellulitis. As he has done dozens of times before, he wrote a prescription for cloxacillin, handed it to the patient, and carried on. While reviewing charts at the end of his shift he suddenly noticed that the patient had a documented penicillin allergy. In a panic, he asked the nurses whether the patient had left. One nurse thought she saw the patient heading toward the pharmacy, so Dr. Porter went to look. He saw the patient speaking with the pharmacist—they had caught the error and were just about to call Dr. Porter. He was so relieved! He thanked the pharmacist and apologized to the patient for the mistake. Together, they reviewed the patients’ allergy history and selected a different antibiotic that was safe. The patient, although at first quite upset, was really pleased with the way the pharmacist and the doctor handled the issue, and appreciated Dr. Porter’s apology.

WHAT ARE INTEGRITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY?

Integrity can be defined as, “A virtue consisting of soundness of and adherence to moral principles and character and standing up in their defense when they are threatened or under attack. This involves consistent, habitual honesty and a coherent integration of reasonably stable, justifiable moral values, with consistent judgment and action over time” (Miller-Keane & O’Toole, 2003). In healthcare settings we can define integrity as encompassing honesty, keeping one’s word, and consistently adhering to principles of professionalism, even when it is not easy to do so. Accountability usually refers to reliability and answering to those who trust us, including our patients, colleagues, and society in general. Dr. Porter demonstrated these attributes when he took responsibility for the error, corrected it, and apologized to the patient.

WHY DO INTEGRITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY MATTER?

Integrity and accountability are fundamental to ensuring trust between the public and healthcare professionals. Physicians’ integrity forms a foundation for patients’ trust and fosters healthy therapeutic relationships that promote healing. Integrity and accountability form the basis of the “social contract” between physicians and society, which grants professionals the privilege of self-regulation. Indeed, as history has shown, this social contract is fragile—if we do not maintain this trust the contract can be rescinded. Perhaps the best-known example of the fragility of the social contract in medicine occurred in Bristol, UK, in the late 1980s, and led to great limitations in the ability of the medical profession to be self-regulating. A summary of the case can be found in Figure 5-1.

There is much to be learned from what is known as the Bristol Affair, and many questions remain unanswered. In retrospect, it is hard to imagine why it took so long before action was taken. One can wonder why no one spoke up when children were dying, or why pediatricians still referred patients to a unit with such bad outcomes. Many health systems’ problems contributed in addition to problems with individual doctors (the inquiry resulted in 109 recommendations for change). Further, data collection and reporting were not as widespread or robust as is the situation today. A full exploration of what happened in Bristol is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the important lesson is that the medical profession was seen by the Inquiry to have failed in its duty to self-regulate. The Bristol affair contributed significantly to major changes in the profession in the United Kingdom. The key change was that the General Medical Council (GMC), which had long been the principal regulatory body for the medical profession, is now itself overseen by the Council for the Regulation of Health Professions, which has the power to intervene if it feels the public interest is not being served, or if it feels that physician-imposed sanctions are too lenient. Therefore, the profession now has a regulatory body overseeing its work; the profession does have input into that process, but the Council (the GMC’s governing body) now has half of its members from the lay community.

Many healthcare practitioners were involved in the poor outcomes in Bristol, but most of the public outrage focused on the surgeons, rather than the other members of the team such as the nurses or hospital. This may be reflective of the way in which physicians and surgeons have traditionally been viewed—as the tops of the hierarchy, or leaders of their teams. In the past, most patients considered their care to be the responsibility of a specific individual physician, who took “ownership” of the accountability to patients. However, increasingly, patient care is considered a team responsibility, with a physician perhaps in a “most responsible” position but with an integrated, multidisciplinary team that takes “ownership” collectively (Park et al, 2007). Individuals may rely more on teams to provide expertise and continuity, yet each person must maintain responsibility for their own behaviors and actions within these teams and systems. That is, the team or system does not dilute the responsibility each professional owes to the patient.

This chapter includes a discussion of the behaviors of individual physicians, healthcare teams, healthcare settings, and professional organizations that can promote the values of integrity and accountability. In the individual physician section, we have used examples in several areas to illustrate how individual physician behaviors can support the values of integrity and accountability. The illustrative topics include confidentiality, use of the Internet, inappropriate relationships with patients, medical error, and managing conflicts of interest.

BEHAVIORS AND SKILLS OF INDIVIDUAL CLINICIANS

Confidentiality is of the utmost importance in patient care. Patients must feel free to discuss openly and without hesitation any aspect of their lives, including sensitive information, trusting completely that this information will be guarded safely by the physician or healthcare professional. We owe it to our patients to protect the information they share with us and, in fact, this is codified in legislation (such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in the United States and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act in Canada). But as easy as it is to outline the importance of maintaining patient confidentiality, it is just as easy to see how breaches can occur. Consider the following scenario:

A surgical team is on the elevator talking about their patient list for the day. At first they are the only ones present, but at one floor three people get on. The senior resident is in mid-sentence, and continues, “We’ll just go in and hack out the bowel. That’s how Dr. Roberts likes to do it—just hack it out. He’ll need a colostomy after but it’s no big deal.” Two of the other residents chuckle, and the three onlookers stand in silence.

Is there an issue of privacy or confidentiality in this scenario? At first you might not think so, as no patient’s name is disclosed and there is no mention of any particular disease. But what if one of the people on the elevator was there to visit a friend or relative about to have bowel surgery? Or if another recognizes Dr. Robert’s name, or is on her way to an appointment with him? The onlookers might reasonably wonder if it’s their loved one being discussed, and may not know (or care to know) about details such as a colostomy. But even if they don’t know anyone having surgery, how might they feel about the cavalier way they see doctors discussing—and laughing about—patients? They might now wonder if all doctors talk about patients this way, or worry that their own doctors might. This behavior is unprofessional not just because of a potential breach in private information, but because it undermines the confidence patients have in their healthcare providers. And it certainly does not speak well for the education system or the institution.

Inadvertent breaches in patient confidentiality may occur in many other ways. For example, we have seen patient sign-out lists left on cafeteria tables, or sticking out of pockets so that patients’ names can be seen. We have all seen and heard patient-related discussions in the coffee line-ups, or hallway consults being conducted in crowded emergency departments. Although this section is about individual behavior, it is important to note that the team has a role to play here as well (e.g., to redirect or halt conversation, ensure sound privacy when presenting and discussing patients, and being careful to keep track of sign-out lists). The institution can also create and support policies that make these breaches less likely to occur, such as ensuring that all patients are seen and examined in private settings, and by not allowing patient lists to be emailed or printed from non-secure computers. In short, this too is a shared responsibility.

Karen is a 3rd-year medical student who just started on her first real clinical rotation. She used to have an active social life, but it has become increasingly apparent that being on call and working long hours will make it difficult for her to keep up with her friends. She maintains an active Facebook page and often shares her thoughts and feelings with her friends and followers. After a particularly rough shift in the emergency department she went home and posted about it, stating that, “The ER tonight was a complete zoo! People were coming in from all directions, with all sorts of issues that were not even real emergencies. They spend years smoking and drinking and not taking care of themselves and then expect us to pick up the pieces. They’re burdening the system and it’s really frustrating.”

Has Karen done anything that might be considered unprofessional? In terms of confidentiality, she hasn’t named anyone or given particularly specific information that could lead to the identification of a particular patient or healthcare provider. But it would not be difficult to figure out to which hospital and/or medical center she is referring. This is an issue of integrity. In a bygone era—before the Internet—she might have said these same words to a friend or family member on the phone. Anyone from those previous generations may wince at remembering how we vented after difficult shifts ourselves. However, two key differences exist. The first is the public nature of the Internet. Although it is possible to restrict one’s presence so that only “friends” can see postings, a recent study showed that only two thirds of medical students activated these settings (MacDonald, Sohn, & Ellis, 2010). Furthermore, because the concept of “friends” is so loose, family members and acquaintances not in the profession may see what’s posted and can then choose to re-post or share with their “friends.” So the information posted can never be thought of as being truly private. The other main issue is that of permanence because what is posted online can potentially be there forever. Tweets, for example, are all archived at the Library of Congress, even if they are later deleted from a user’s account or timeline. Venting to a friend on the phone may have compromised some rules of professionalism (such as use of derogatory language about patients), but it did not have the staying power (or damaging potential) of a similar rant online.

LEARNING EXERCISE 5-1

Think of a recent time where you witnessed (or were party to) a breach in confidentiality.

Describe what happened. Who was involved? What was the nature of the information that was breached?

Was anything done or said at the time to interrupt or stop the breach from occurring? In retrospect can you think of anything that could have been done?

Was anything done or said after the fact, either to the individual(s) who lapsed or to others?

What strategies could your institution put in place to reduce the occurrence of these sorts of lapses?

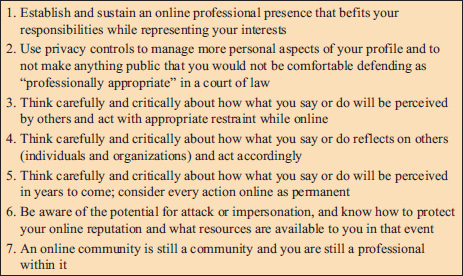

Studies of medical students report that most students and residents have an online presence, and find it essential for keeping up with their social lives while on busy clinical rotations. Some try to resolve this by creating two online personae—one personal and one professional—but this can become burdensome and confusing, and it’s easy to slip between them (just as it is unfortunately easy to hit “reply to all” when sending a private email). Students often report feeling constricted in developing identities as professionals, while struggling to maintain a sense of their old selves, and this tension can lead to lapses in professionalism. In one study, students felt that guidelines would be helpful to teach them about boundaries, confidentiality concerns, and other issues related to online professionalism—but they rejected the idea of “rules,” as they did not think it was fair to attempt to regulate their social lives (Chretien et al, 2010). In their view, if we trust students to look after patients, we should trust them to know right from wrong when it comes to social networking. It is with this spirit in mind that many guidelines for “digital professionalism” have been created. Rather than attempting to restrict or regulate what healthcare professionals can and cannot do online, they provide information and guidelines for use (Figure 5-2). The idea is that these guidelines should be educational for all involved.

The preceding example focused on a medical student who used derogatory language about patients online, but similar issues arise when students post personal content about themselves. Studies have found that healthcare students and professionals often post personal information and photographs of themselves, including those from vacations, parties, and social occasions. Students have appeared intoxicated or partially undressed. Apart from the obvious concerns discussed previously about who might view these postings and the potential for permanence, this highlights another issue, that of the tension between the “person” and the “professional.” Students often struggle when developing their new identities as healthcare professionals and sometimes chafe against new rules and constraints on their behaviors. But it is important to note that medical authorities and licensing bodies do not make this distinction, and precedents exist for physicians to be publicly sanctioned and reprimanded for behaviors that occur well outside the healthcare setting (e.g., incidents of “road rage” and personal income tax evasion).

Thus it is our duty as educators to teach and guide students and residents, and to ensure that they are fully aware of what is expected of them as they develop into professionals. A recently published policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards included this helpful table to help guide physicians and trainees (Table 5-1) (Farnan et al, 2013).

| Activity | Potential benefits | Potential pitfalls | Recommended safeguards |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

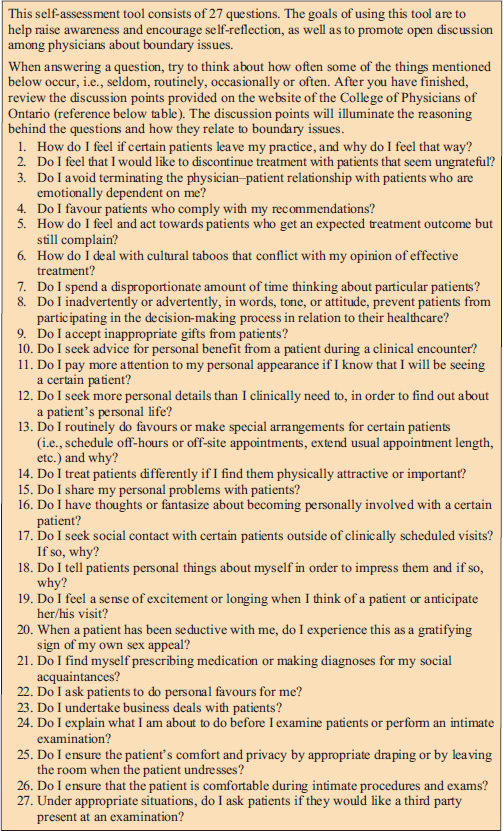

Clinicians have ample opportunity to demonstrate integrity and accountability when it comes to their relationships with patients. Maintaining appropriate boundaries is a fundamental skill that all healthcare professionals must learn, and it is an area in which lapses, when they occur, can be particularly serious and damaging. Everyone has heard or read of cases in which physicians have become sexually involved with their patients. Thankfully, these occurrences are relatively rare overall, but they are still one common reason for physicians to lose their license to practice medicine (Alam et al, 2011). All healthcare professionals will recognize that behaviors such as assaulting one’s patients are clearly wrong, but some controversy exists around other types of boundary issues.

For example, although it is usually considered undesirable for a physician to enter into a friendship or social relationship with a patient, it is important to remember that context matters. If you are the only physician in a small or remote town it is inevitable that you will form friendships with your patients, otherwise you would be completely isolated. However, rules and policies exist for guidance and it is paramount that patients’ needs remain the priority (American Medical Association, 2013a). Of interest, physicians’ support for such relationships has been found to differ based on certain contextual factors. In one survey study of more than 1600 physicians, social and business relationships with patients were thought to be potentially acceptable by 91% and 65% of respondents, respectively, but it was much less supported by women, nonwhites, and international graduates (Regan, Ferris, & Campbell, 2010).

Some authors have drawn distinctions between boundary violations and boundary crossings, which are thought to be milder and more innocent, but which might, over time, develop into violations. One commonly cited example of a boundary crossing is an elderly patient who gives homemade cookies to her family doctor. Refusing such a gift may do more harm than good, by embarrassing the patient and making her feel self-conscious or uncomfortable. Instead, one might thank the patient, being sure to inform her that gifts are not necessary, and share the cookies with the entire office, making the gift seem less personal. On the other hand, if a patient brings gifts to every encounter, or the gifts are expensive or personal in nature, it is a different story. The physician should be aware that accepting such gifts is considered to be undesirable, because it runs the risk of altering the physician–patient relationship and contributes to a loss of objectivity. This can affect patient care by consciously (or unconsciously) treating that patient’s symptoms as more or less serious, or being persuaded to order unnecessary tests or treatments.

Receiving gifts from patients is an example of the daily challenges to boundaries that occur in all practices. Although avoiding these challenges is desirable, it is not always possible, so the goal here is to learn how to respond to them in a professional manner. Figure 5-3 presents a sample self-assessment tool that can assist physicians handle such challenges.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree