Vulvar Squamous Lesions

Benign Squamous Neoplasms

Condyloma Acuminatum

Microscopic Features

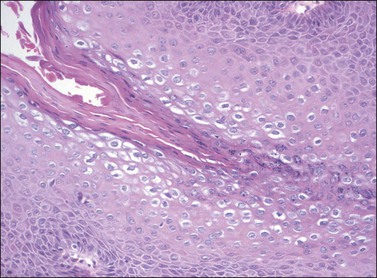

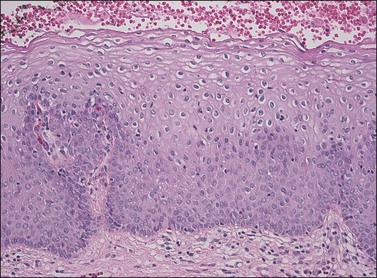

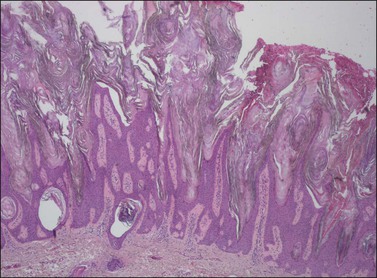

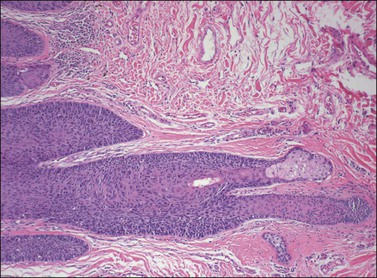

On histologic examination, the lesion consists of complex branching fibrovascular cores covered with acanthotic squamous epithelium, frequently with accompanying hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Pathognomonic findings include basal and parabasal hyperplasia, with koilocytic atypia, manifested by enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular, wrinkled nuclear membranes accompanied by a region of perinuclear clearing or ‘halo,’ in the upper third of the epithelium (Figures 4.1 and 4.2).

Figure 4.1 Condyloma acuminatum. A complex formation of branching fibrovascular cores is lined by a slightly thickened epithelium with hyperkeratosis apparent on the surface and koilocytic atypia in the superficial third of the epithelium.

Seborrheic Keratosis

Microscopic Features

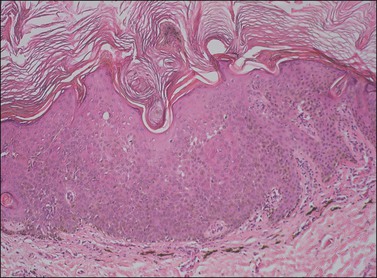

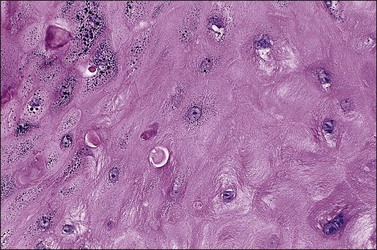

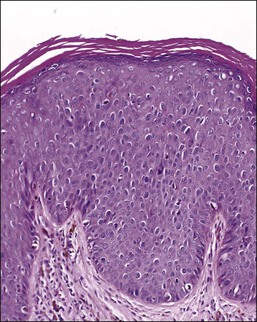

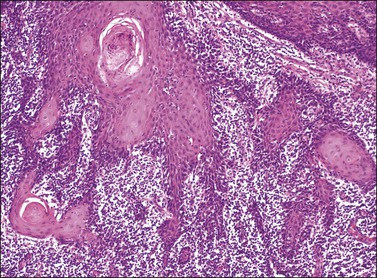

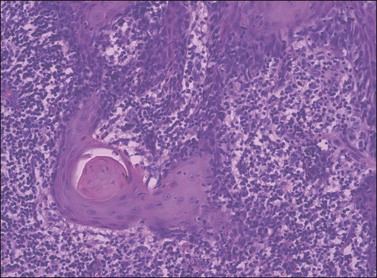

The epidermis is thickened by a population of cells with basaloid morphology, without significant nuclear atypia or mitotic activity, and with pronounced surface hyperkeratosis. Pigmentation of the basal and parabasal cells is usually evident. Invaginations of the surface epithelium result in the accumulation of hyperkeratotic material below the surface of the lesion, in what may appear to be cystic spaces, forming the structures known as ‘horn cysts’ (Figure 4.3). Follicular plugging with this hyperkeratosis is also typical. ‘Squamous eddies,’ rounded whorls of squamous cells named for their resemblance to swirling currents in a stream, may be found (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.3 Seborrheic keratosis at low power, showing marked hyperkeratosis at the surface and keratin horn cysts toward the base.

Differential Diagnosis

On occasion, reactive changes secondary to trauma or prominence of squamous eddies can be suggestive of squamous cell carcinoma. Key to establishing the correct diagnosis in such cases is the absence of an infiltrative growth pattern. Other entities in the differential diagnosis of seborrheic keratoses on the vulvar skin include condyloma acuminatum, VIN, and melanoma. The papillary architecture and hyperkeratosis of seborrheic keratosis can be suggestive of condyloma, particularly at low power. As seborrheic keratoses are frequently found to contain HPV DNA,1,2 some authors have maintained that these lesions are, in fact, variants of condyloma,3 although this remains controversial. The absence of koilocytic atypia in seborrheic keratosis and of keratin horn cysts in condylomata will usually resolve the diagnosis. The lack of significant nuclear atypia or mitotic activity is also of use to differentiate seborrheic keratosis from VIN and melanoma, with immunohistochemistry of further use in distinguishing the latter.

Keratoacanthoma

Definition

Keratoacanthoma is a distinctive keratinocytic neoplasm characterized by rapid growth and spontaneous regression. Although often considered a low-grade variant of squamous cell carcinoma, this view is not universally accepted,4–6 and as there have been no reported cases of malignant behavior in cases presenting on the vulva, we present it here as a benign neoplasm.

Clinical Features

Keratoacanthoma characteristically presents as a rapidly growing pink or flesh-colored, firm, well-demarcated dome-shaped lesion with central umbilication. Although common on the sun-exposed skin of the elderly, very few cases occurring on the vulva have been reported.7–10

Microscopic Features

The dome-shaped, umbilicated lesion observed on the skin corresponds to an endophytic proliferation of squamous cells forming a keratin-filled crater-like center rimmed by collarette, or ‘buttressing lips,’ of epidermis. The central squamous cells are well differentiated and tend to become larger toward the center of the proliferation, accumulating abundant glassy, eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figures 4.5 and 4.6). In the early stages of development, mitoses may be numerous and mild to moderate nuclear atypia may be present, but these features regress as the lesion matures, and when well developed only minimal atypia is present. The lesions typically have a rounded, pushing border with a dense inflammatory infiltrate at the base of the lesion.

Figure 4.5 Keratoacanthoma at low power, with a ‘buttressing lip’ of normal epidermis visible on the left side of the lesion.

Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions of the Vulva (VIN)

Definition

About 90% of squamous intraepithelial lesions of the vulva are HPV related, comprising a spectrum of alterations ranging from low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions VIN (VIN 1), sometimes characterized as ‘flat condyloma,’ to the severe full-thickness dysplasia of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion VIN (VIN 3). Recent proposals from both the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISVVD) and the College of Pathologists (CAP)/American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) have advocated replacement of the older three-tiered system used to describe these lesions with a two-tiered system (Table 4.1).11–13

Table 4.1

Commonly Used Classification Schemes for Intraepithelial Disease of the Vulva

| 1986 VIN Terminology | 2009 ISSVD Terminology | 2012 CAP/ASCCP Terminology |

| VIN 1 | Condyloma HPV changes | Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (VIN 1) |

| VIN 2 | VIN, usual type (uVIN) | High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (VIN 2–3) |

| VIN 3 | VIN, usual type (uVIN) or VIN, differentiated type (dVIN) | High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (VIN 2–3) or VIN, differentiated type |

HPV-Related Low- and High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (VIN 1–3)

Clinical Features

Patients with HPV-related squamous intraepithelial lesions are usually in their thirties or forties, frequently smokers, and frequently have a history of, or concurrent, multifocal vulvar lesions and/or multicentric oncogenic HPV-related disease, or other sexually transmitted diseases.14–21 Pruritus is the most common symptom.20,21 Other symptoms may include pain, ulceration, or dysuria. Approximately 20% of patients are asymptomatic, but may have observed an abnormal area on self-examination.22,23

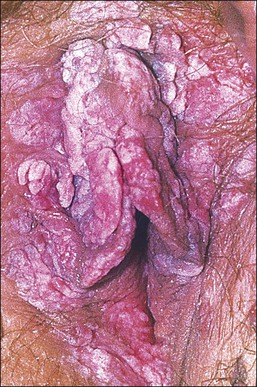

The gross appearance of the lesion is variable. Lesions are usually well demarcated and asymmetric, may appear red, white, pigmented, or mixed, and may be raised, papular, flat, or ulcerated (Figures 4.7 and 4.8).

Pathogenesis/Etiology

The majority of low-grade HPV-related vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSILs) contain low-risk HPV subtypes, while high-grade lesions (HSILs) typically contain high-risk subtypes, most commonly HPV 16. The estimated time of progression from incident infection to the development of clinical disease has been estimated at 18.5 months.23

Microscopic Features

LSIL of the Vulva (VIN 1).

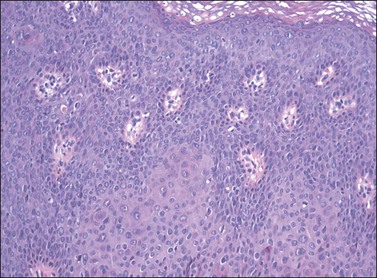

Not all authors agree on the value or significance of the category of LSIL (VIN 1), although there is general agreement that it is a rare and poorly reproducible diagnosis.23–25 The controversy stems from disagreement as to the biologic behavior of these lesions.12,26–28 Because of its distinctive, albeit uncommon, morphology and its as yet unclear behavior, we prefer to maintain this diagnostic category for flat-macular lesions with epithelial changes resembling those of exophytic condylomata (Figure 4.9).

HSIL of the Vulva (VIN 2–3).

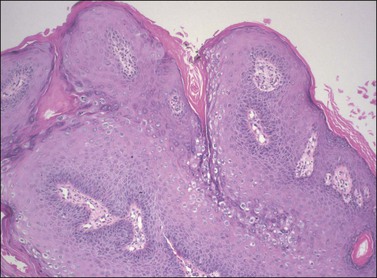

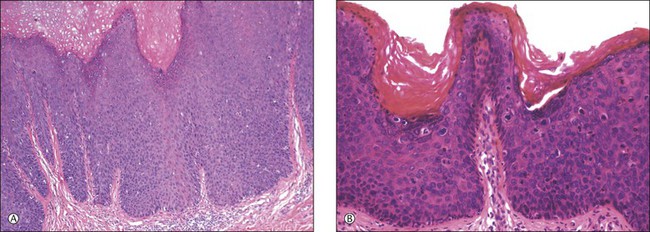

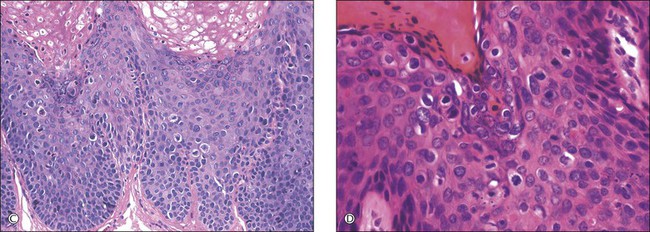

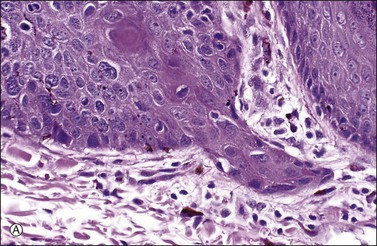

For descriptive purposes, high-grade HPV-related lesions of the vulva have been divided into warty and basaloid subtypes. Warty lesions (Figure 4.10A–D) are characterized by a spiky or undulating surface, giving them a condylomatous gross appearance. The markedly thickened epithelium forms wide, deep rete pegs separated by thin dermal papillae that often closely approach the surface. Disorganization and abundant mitotic figures, including abnormal ones, can be seen in all levels of the epithelium, with evidence of maturation and often koilocytic change in the upper layers. Hyperkeratosis is prominent, often with accompanying parakeratosis. Nuclei are enlarged and hyperchromatic, with irregular nuclear membrane contours and prominent pleomorphism. Multinucleated cells, as well as dyskeratotic cells, may be present. An appreciable amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm is present, and the cell borders are easily delineated. Lesions with this morphology were formerly subclassified as VIN 2 or VIN 3, by determination of the proportion of the epithelium populated by relatively immature cells, with those having immature cells involving no more than two-thirds of the epithelium classified as VIN 2 (Figure 4.11) and those having immature cells involving more than two-thirds of the epithelium as VIN 3.

Figure 4.10 (A) VIN 3, warty type, showing acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and widened, deep rete ridges. (B) Extension of a long narrow dermal papilla close to the surface is seen in the center of this image. Numerous mitotic figures and dyskeratotic cells can be appreciated throughout all layers of the epithelium. (C) Marked nuclear pleomorphism in warty VIN 3, with surface hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. (D) At high power, prominent nuclear atypia, numerous mitotic figures, apoptotic bodies, and dyskeratotic cells are easily identified.

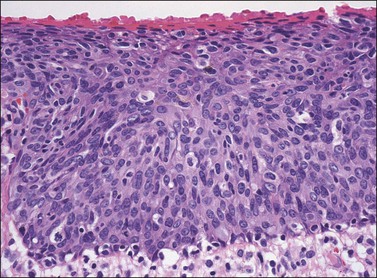

In contrast to warty lesions, the surface of basaloid lesions is relatively flat. Hyperkeratosis and koilocytosis may be present, but to a lesser degree than is seen in warty lesions. The epithelium is thickened by a relatively uniform population of immature cells with scant cytoplasm, poorly defined cell borders, and enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 4.12). As in warty lesions, mitotic activity is readily identified and atypical mitotic figures may be present.

Figure 4.12 VIN 3, basaloid type. A disorganized proliferation of immature cells with nuclear atypia and polymorphism fills the entire thickness of the epithelium.

Distinction between warty and basaloid subtypes is not always easy. Mixed forms, containing morphologic features of both types, are not uncommon, and may be designated as such (Figure 4.13), although, as there is no clinical difference between lesions of either morphology, specification is not required for diagnosis.

Routine Biomarkers of Clinical Relevance

Immunohistochemistry for Ki-67 can be useful in identification of LSIL, where it can highlight an abnormal degree of proliferation in a cytologically equivocal lesion.28 Of greater utility in the diagnosis of HSIL is p16INK4a; as a reliable indicator of the presence of high-risk HPV in the vulva,19,29 it is strongly positive throughout most of the epithelium in HSIL (VIN 3).19,29,30

Differential Diagnosis

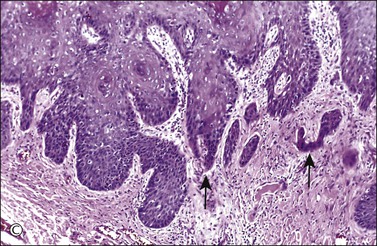

Although both condyloma acuminatum and warty HSIL (VIN 2–3) may have prominent koilocytic changes, the latter can be distinguished by the presence of atypical, pleomorphic cells in the deeper levels of the epithelium and by the presence of increased mitotic activity, including abnormal mitotic figures, in the upper layers. Seborrheic keratosis and lichen simplex chronicus may have acanthosis and hyperkeratosis, but typically lack the nuclear atypia of HSIL (VIN 2–3). Probably the most common diagnostic dilemma in assessment of HSIL (VIN 2–3) is distinction of truly intraepithelial disease from disease with associated early invasion. This can be complicated by involvement of skin appendages, which may extend quite deeply into the underlying dermis. The distinction rests on the preservation of a distinct epithelial–dermal junction, without an inflammatory response or stromal desmoplasia (Figure 4.14). The border along the basement membrane in intraepithelial lesions should be smooth, while in early invasion irregularly shaped tongues of cells protrude from the basal layer through the basement membrane (Figure 4.15). Often this is accompanied by ‘paradoxical maturation’ of the cells on the invasive front, with the cells enlarging and accumulating more abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4.16). Early invasive nests of squamous cell carcinoma are small, irregularly shaped, and usually accompanied by a desmoplastic response (Figure 4.17).

Figure 4.14 VIN 3 with skin appendage involvement. The cells of VIN 3 are palisaded along the periphery of the hair follicle. The involvement does not completely replace the normal epithelium in this case, and the terminal portion of the hair follicle and adjacent sebaceous gland are unaffected. Note how deep the hair follicle extends into the dermis compared with the adjacent epithelium.

Figure 4.15 Early invasion by squamous cell carcinoma, with irregular fingers and nests protruding into the dermis. Note the ‘paradoxical maturation’ of the cells toward the center of the larger cell groups.

Figure 4.16 ‘Paradoxical maturation’ with formation of a keratin pearl in an irregularly shaped protrusion of early invasion.

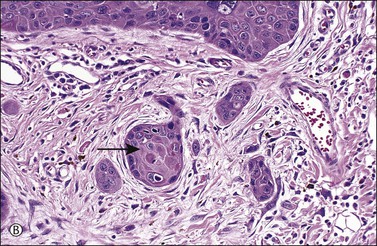

Figure 4.17 Microinvasive squamous cell cancer. (A) Early stromal invasion with a tiny tongue of tumor protruding from the basal most epithelium. (B) The small nests of tumor cells are distinctly separate from the overlying epidermis, sometimes have irregular shapes and lie in a desmoplastic stroma, and sometimes exhibit invasive cells with increased and more eosinophilic cytoplasm than neighboring basal cells. The microinvasive component is easy to recognize (arrow). (C) Some foci are easily recognized as microinvasive (arrows), whereas the bulbous tips of the overlying epidermis that are composed of small basal cells are considered as VIN 3.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree