Vulvar Cysts, Adenocarcinoma, Melanocytic, and Miscellaneous Lesions

Common Acquired Melanocytic Nevus

Melanocytic Nevus of the Genital Type

Blue Nevus (Dermal Melanocytoma)

Atypical (Dysplastic, Clark) Nevus

Skin Appendage Neoplasms and Lesions of the Anogenital Mammary-Like Glands

Rare Tumors and Tumor–Like Conditions

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Histiocytosis X)

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (Trabecular Carcinoma, Small Cell Carcinoma of the Skin, Primary Cutaneous Neuroendocrine Carcinoma)

Cysts

Follicular (‘Epidermoid’) Cyst

Clinical Features

Follicular cyst presents as a solitary, creamy-white or yellowish lesion on the labium majus (Figure 5.1). It is generally asymptomatic, but rupture may induce inflammation with enlargement, tenderness, erythema, and induration. Follicular cysts usually occur spontaneously and after age 30. Onset at an early age or occurrence in great numbers should prompt consideration of Gardner syndrome.

Microscopic Features

Most vulvar follicular cysts represent dilatations of the most distal portion of the follicle, the infundibulum, hence they have thin, flat, squamous epithelium lacking rete ridges, contain a granular layer, and are filled with loose-packed keratin. Its rupture may lead to leakage of keratin, resulting in an acute and chronic inflammatory foreign-body reaction.

Steatocystoma Multiplex

Clinical Features

Steatocystoma multiplex is the dominantly inherited occurrence of numerous small, creamy-colored cysts exhibiting sebaceous ductal differentiation. The lesions usually appear after adolescence and may be solitary. Most common locations are the presternum, axillae, abdomen, and labia majora. Rarely, they first present as multiple vulvar cysts at an older age1 (Figure 5.2).

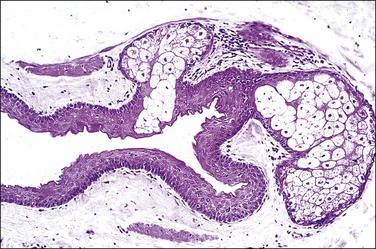

Microscopic Features

Steatocystomas are composed of an intricately folded, thin layer of stratified squamous epithelium lined internally by a corrugated, thin, compact, and strongly eosinophilic cuticle, lacking a granular layer. There may be associated small sebaceous glands (Figure 5.3). Although this finding raises the differential diagnosis of dermoid cyst, the latter is extremely rare in the vulva and shows miniaturized hair follicles.

Bartholin Cyst

Definition

Bartholin cyst is the cystic dilatation of a major vestibular (Bartholin) gland or its duct.

Clinical Features

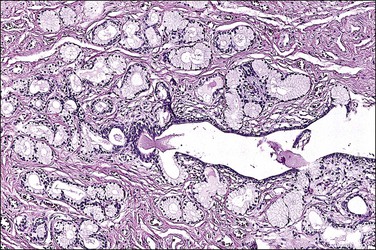

Bartholin cyst is the most common form of vulvar cyst, and is the presenting complaint for 2% of women during their annual gynecologic visit.2 The Bartholin glands (Figure 5.4) are located behind the labia minora and their ducts open into the posterior lateral vestibules, just anterior to the hymeneal tegmentum. Bartholin cysts result from blockage of the drainage duct and resultant retention of secretions, perhaps following infection. Bartholin cysts are most common in the reproductive years. If large, they may partially obstruct the introitus. Bartholin cysts usually present as smooth-domed nodules, generally 1–10 cm in diameter. If brown or blue, they may be mistaken clinically for melanocytic nevi. The cysts contain mucoid fluid, which stains with mucicarmine, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS; with and without diastase), and Alcian blue at pH 2.5. They may recur after incision and drainage, and may require surgical excision, particularly in postmenopausal women, to rule out the possibility of associated carcinoma. Bartholin abscess is an acute process usually caused by Neisseria gonorrheal infection. Excision, drainage, and antibiotics are the treatments of choice.

Microscopic Features

Bartholin cysts show a lining of transitional epithelium, with frequent focal squamous metaplasia (Figure 5.5). Smaller mucus-filled cysts may show some remnant of the original mucus-secreting glandular epithelium, but it may be flattened or cuboidal. Normal remnants of mucus glands may be presented adjacent to the cyst. Microscopically, the Bartholin duct abscess shows abundant neutrophilic infiltrate within the stroma surrounding the duct.

Mucinous Cyst

Microscopic Features

These cysts are lined almost entirely by columnar or cuboidal mucus-secreting epithelium like that of endocervical glands without peripheral muscle fibers or myoepithelial cells. Foci of squamous metaplasia are sometimes present; they are considered to be of urogenital sinus origin.3

Ciliated Cyst (Paramesonephric Cyst)

An occasional cyst may be lined partially by ciliated columnar epithelium (Figure 5.6). Usually this occurs as a focal change within a mucinous cyst or a Bartholin cyst; it is likely a nonspecific metaplastic change.

Paraurethral (Skene) Gland Cyst

Definition

Paraurethral gland cyst is the cystic dilatation of the paraurethral (Skene) gland or its duct.

Clinical Features

The paired paraurethral glands (the female homolog of the male prostate gland) are located on either side of the urethral meatus. Ductal occlusion, probably a consequence of infection (e.g., gonococcal), leads to formation of a retention cyst, generally less than 2 cm in size, located in the upper lateral introitus. Paraurethral gland cysts affect from neonates to premenopausal women, with an incidence of 1 per 2000–7000 women.4 Patients may be asymptomatic or complain of urinary obstruction or dyspareunia. Surgical excision should be done after medical therapy for any underlying infection.5

Cyst of the Canal of Nuck

Clinical Features

These cysts are most common in the inguinal canal, where they must be distinguished from hernias. They also occur in the mons pubis and in the superior, outer region of the labium majus. Ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful for definitive clinical diagnosis. They are homologous to hydroceles in males.6 The processus vaginalis peritonei (canal of Nuck) is a rudimentary sac of peritoneal mesothelium carried down by the round ligament as it passes through the inguinal canal7,8 and inserts into the labium majus. Failure of this structure to obliterate normally during fetal development leads to blockage and cystic dilatation. While these cysts are usually solitary, more than one may arise if obstruction occurs at multiple sites. Generally asymptomatic, they may become tender to pressure, and may then require a procedure similar to herniorrhaphy.

Microscopic Features

In their pristine state, these are thin-walled and lined by flattened mesothelium. By the time they present clinically, repeated external trauma has usually induced fibrosis of their walls, reduced or destroyed their mesothelial lining, and caused hemosiderin deposition from old haemorrhage.9

Extramammary Paget Disease

Definition

Extramammary Paget disease10 is a form of in situ adenocarcinoma of the squamous mucosa. For a number of these cases, recent evidence suggests an origin from Toker cells, which are found in the breast with clear cytoplasm that reacts for cytokeratin 7 (CK7)10–13 and are thought to derive from the ostia of the mammary-like glands found in the vulva, perineum, and perianal skin.

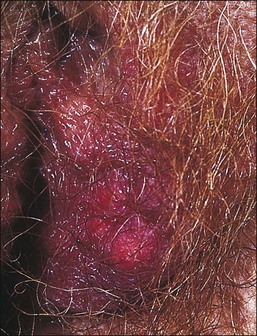

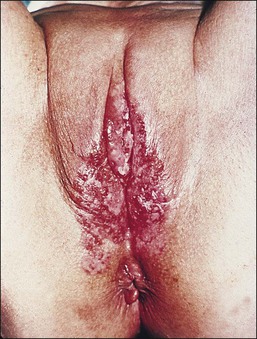

Clinical Features

The vulva is the most common site of extramammary Paget disease, accounting for about 5% of all vulvar neoplasms. It usually presents in older women as a moist, red, eroded or eczematous-appearing plaque. One or both sides of the vulva can be involved, often with spread to the perianal skin (Figure 5.7). The plaques are usually irritated and sore, and may be clinically misinterpreted as an inflammatory skin disease (e.g., intertrigo, fungal infections, immunobullous disorders, Hailey–Hailey disease). The diagnosis requires biopsy confirmation.

Treatment may be difficult because the disease usually extends well beyond the clinically apparent margins. Moreover, even surgical margin status is not particularly helpful in predicting recurrence, as about a third of patients experience recurrence regardless of whether the margins after initial surgery are positive or negative. The extent of the operation (wide local excision, simple vulvectomy, or modified radical vulvectomy) during the initial treatment also poorly correlates with disease recurrence. Mohs micrographic surgery, topical chemotherapy, and photodynamic therapy may play a role in selected cases. HER-2/neu expression has been demonstrated by some Paget disease of the vulva;14 thus, some patients may benefit from trastuzumab (Herceptin), a recombinant monoclonal antibody against HER-2/neu.

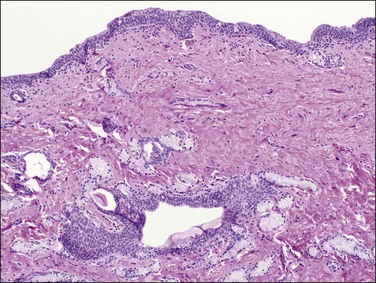

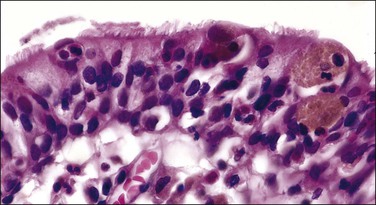

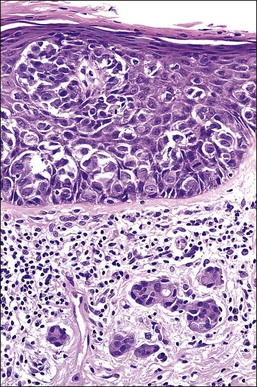

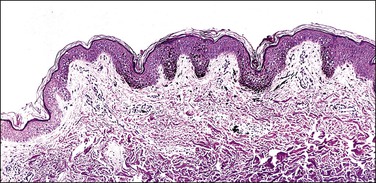

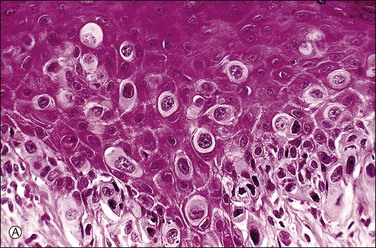

Microscopic Features

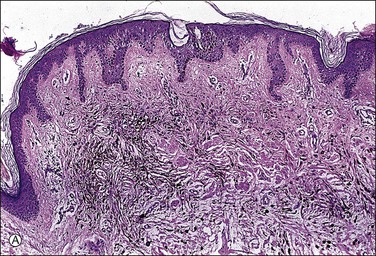

Histologically, the epidermis contains pale-staining cells that are larger than adjacent keratinocytes, arranged singly or in small to large nests (Figure 5.8). When numerous, Paget cells may replace much of the epidermis, which appears swollen and thickened (Figure 5.9). When Paget cells are single or few in number, they appear to be mainly above the basal layer or individually (pagetoid migration) into the upper epidermal layers. Cells appear not to be connected with the basement membrane and thus are different from melanoma in situ (see later; Figure 5.10A). Paget cells may even be found growing down hair follicles as well as eccrine glands (Figures 5.11 and 5.12). Occasionally, similar cells may be seen in the underlying dermis (Figure 5.13), indicating invasion. While up to 50% of patients are reported to show invasion in some series,15 this is a distinctly unusual happening in our experience. Likewise, we find that metastases to lymph nodes are exceedingly rare.

Figure 5.8 Paget disease. Nests of pale-staining tumor cells are located within the epidermis including the upper layers. The nests compress the basal layer of squamous cells.

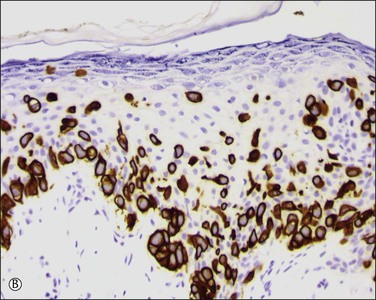

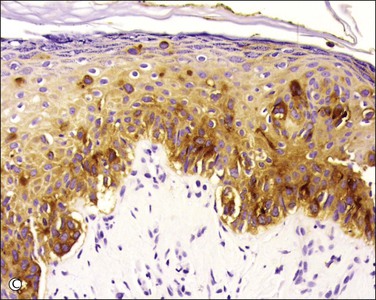

Figure 5.10 Paget disease. (A) The tumor cells have abundant pale cytoplasm and are arranged singly or in small clusters within the epidermis. They appear larger than the surrounding keratinocytes. (B) Paget cells express CK7 and (C) CEA.

Figure 5.12 Paget disease involving sweat glands. (A) Low-power section of skin in which the involved gland (arrow) extends near to the cutaneous fat. (B) Detail of gland cut in cross section.

The pale cytoplasm of the Paget cell is usually finely granular, and the nuclei are central and round to oval. Mitotic figures may be found. On routine staining, Paget disease may be confused with melanoma in situ. However, the Paget cells at the basal layer are usually discrete and characteristically compress and displace the normal keratinocytes, whereas melanoma cells generally form a continuous proliferation close to the basement membrane.

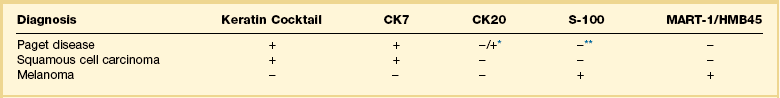

Paget cells usually contain intracytoplasmic mucin (neutral and acidic), as highlighted by PAS-diastase, Alcian blue, colloidal iron, and mucicarmine stains. In problematic cases, immunohistochemistry may be useful (Table 5.1), with Paget cells selectively expressing cytokeratins CAM 5.2, CK7 (Figure 5.10B), MUC5AC, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (Figure 5.10C), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (BRST-2). About one-fifth of Paget cases are reactive for CK20.16 Since S-100 protein is also sometimes expressed, such cases may require study for more specific melanocytic markers (MART-1/Melan-A, HMB45, etc.). A possible pitfall is those cases in which the tumor cells contain melanin pigment since the interspersed melanocytes may show prominent dendrites and thus may be interpreted as melanoma cells.17 Androgen receptors can be detected in some cases.18

Table 5.1

Immunohistochemical Panel in the Differential Diagnosis of Extramammary Paget Disease, Squamous Cell Carcinoma, and Melanoma

*CK20 is usually negative in extramammary Paget disease. However, it is positive in cases of carcinoma of the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract.

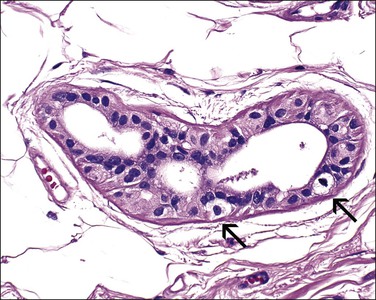

The origin of extramammary Paget disease is controversial. Some cases represent epidermotropic adenocarcinomas, but, unlike mammary cases (in which an underlying ductal carcinoma is almost invariably present), an underlying carcinoma is only rarely detected. Other postulated origins include a pluripotential stem cell within the epidermis or in situ malignant transformation of cells in the cutaneous sweat ducts as they insert into the epidermis. The most recent works point to the Toker cell11–13 (Figure 5.14), which in the breast is an intraepidermal clear cell with bland nuclear features that is reactive for CK7 but not CK20.12 Cytogenetic findings suggest that at least some cases of Paget disease arise multicentrically within the epidermis from pluripotent stem cells,19 and have a molecular basis differing from other vulvar carcinomas.20

Figure 5.14 Toker cells (arrows) with abundant clear cytoplasm in an isolated anogenital mammary-like gland of the vulva.

Melanocytic Lesions

Lentigo

Clinical Features

Lentigines are common on the labia majora or minora. They are often deeply pigmented but usually have uniform color, sharp circumscription, and regular borders. Lentigines proper are not precursors of melanoma.21

Common Acquired Melanocytic Nevus

Definition

A melanocytic nevus is a benign neoplasm composed of cells exhibiting melanocytic differentiation.

Clinical Features

Melanocytic nevi are the most common neoplasms to occur in humans. An average Caucasian adult has 10 or more. Nevi occur with some frequency on the vulva, usually on the labia majora (Figure 5.16).

Microscopic Features

Intradermal, junctional, and compound nevi resemble those seen elsewhere in the body. A key element in assessing the benignity of a melanocytic lesion is to determine the presence of ‘maturation,’ i.e., the tendency to undergo a morphologic shift with progressive depth in the dermis as seen on both light microscopy and immunohistochemical expression.22 Another hallmark of benignity is a tendency for quiescence in the deeper component, with reduced numbers of proliferating cells in the deeper dermis23 and absence of mitotic figures. In contrast, most melanomas consist of large, pleomorphic cells throughout the entire lesion and exhibit mitotic figures in their deep component. However, an uncommon subset of melanomas exhibits a paradoxical pattern of maturation simulating that of nevi.24 A possible pitfall is the presence of mitotic figures in otherwise benign nevi from pregnant women.25

Melanocytic Nevus of the Genital Type

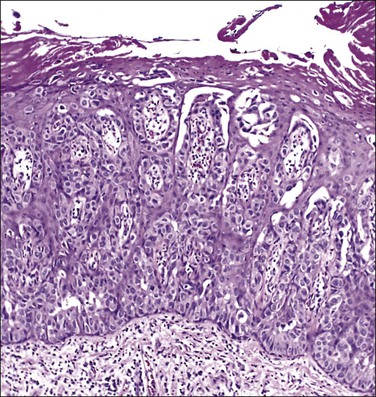

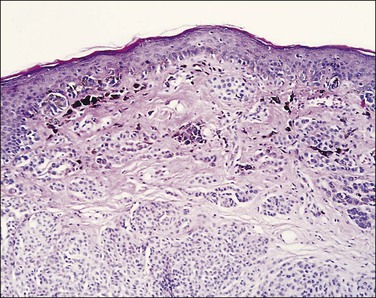

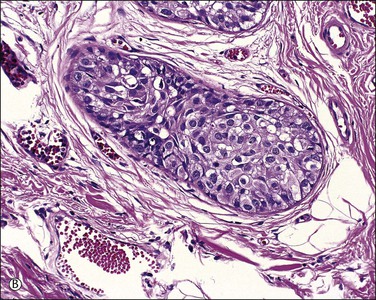

Microscopic Features

These nevi show confluent and enlarged nests of nevus cells that vary in size, shape, and position at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 5.17). The nevus cells exhibit reduced cohesion. Finally, the stromal pattern at the dermoepidermal junction is often inconspicuous and nondescript in contrast to the concentric eosinophilic fibroplasia or lamellar fibroplasia seen in the usual atypical (dysplastic) nevus (see later).

Blue Nevus (Dermal Melanocytoma)

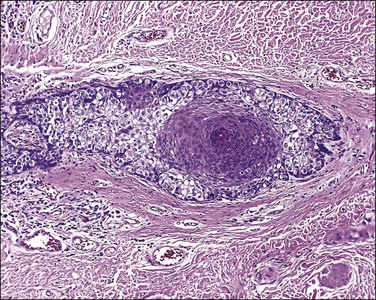

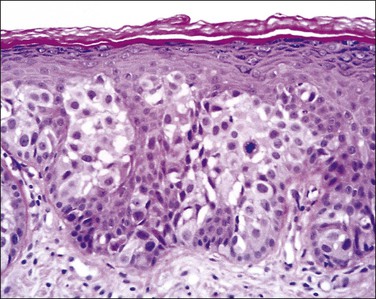

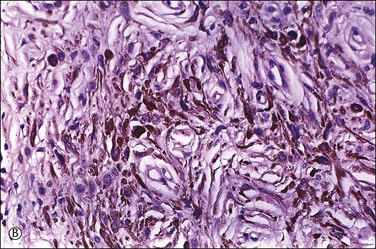

Microscopic Features

The dermis has collections of spindle-shaped or dendritic cells containing delicate melanin pigment, intersecting with dense collagen fibers (Figure 5.18). There are also melanophages containing coarse, clumped melanin pigment. In the cellular variant, the nevus cells are packed in dense fascicles, often forming a dumbbell-shaped nodule that may extend into the subcutis. Malignant change in blue nevi is extremely rare.26 We discourage the use of the term ‘malignant blue nevus’ and rather recommend ‘melanoma blue-nevus type’ for such melanoma cases showing spindle cells and pigmented melanocytes/melanophages (i.e., resembling blue nevus). Blue nevi with necrosis or mitotic figures or cytologic atypia are usually described as atypical forms27 and probably warrant conservative excision.

Figure 5.18 (A) Blue nevus. (B) Dendritic, finely pigmented melanocytes with scattered, coarsely pigmented macrophages.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree