and Natalia Buza1

(1)

Department of Pathology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

Keywords

Vulvar neoplasmsVaginal neoplasmsSquamous cell carcinomaClear cell carcinomaVulvar Paget diseaseMesenchymal neoplasmsMalignant melanomaIntroduction

Tumors of the vulva and vagina share overall histological classifications of neoplastic lesions into squamous, glandular, melanocytic, and mesenchymal tumors. Squamous carcinoma is by far the most common primary malignancy involving both organs and is related to human papillomavirus infection in the majority of cases. Squamous intraepithelial lesion is the most common preinvasive condition of squamous cell carcinoma. Conventional Mullerian adenocarcinomas are rare malignancies of the vulva and vagina. Extramammary Paget disease represents a special form of intraepithelial glandular malignancy and is only rarely associated with an invasive component. Primary clear cell carcinoma of the vagina has been famous for its association with intrauterine diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in the past but is very rare nowadays. Melanoma accounts for 5 % of vulvar cancers and is capable of widespread metastases. A variety of benign and malignant mesenchymal tumors also occur in the vulvar and vaginal regions with benign angiomyofibroblastoma and deep aggressive angiomyxoma primarily involving these areas.

Since both organs are easily accessible for biopsy diagnosis, requests for frozen section diagnosis are relatively uncommon for clinical management of vulvar and vaginal neoplasms. The single most common intraoperative consultation is frozen section evaluation of tumor resection margins for squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma [1]. Other frozen section indications include presence of multifocal synchronous tumors and assessment of lymph nodes for metastatic disease. Frozen section diagnosis is rarely initiated to rule out malignancy of unexpected vulvar or vaginal mass lesions.

Squamous Lesions

Benign Squamous Lesions

Squamous hyperplasia

Benign hyperplastic condition, often associated with lichen sclerosus

Presence of acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis

Lack of human papillomavirus cytopathic changes, inflammation, or stromal fibrosis

Squamous papilloma

Papillomatous proliferation of bland squamous cells with appropriate maturation and without evidence of human papillomavirus cytopathic changes or dysplasia

Condyloma acuminatum

Papillomatous squamous proliferation with fibrous stroma.

Marked acanthosis, parakeratosis, and hyperkeratosis are common.

Presence of koilocytes.

Nuclear enlargement, multinucleation, hyperchromasia, irregular or raisinoid nuclear membranes, and perinuclear halo.

Koilocytosis may be focal and involves clusters of superficial squamous cells.

Prominent granular cell layer with keratohyalin granules is also characteristic.

Seborrheic keratosis

Elevated proliferation of basaloid squamous cells with a smooth, flat base.

Multiple keratin (horn) cyst formation.

Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis are common.

Frequently increased melanin pigment in the basal and parabasal layers.

No cytological atypia or significant mitotic activity.

May be complicated by human papillomavirus infection (condyloma with features of seborrheic keratosis).

Lichen sclerosus (LS) (Fig. 2.1)

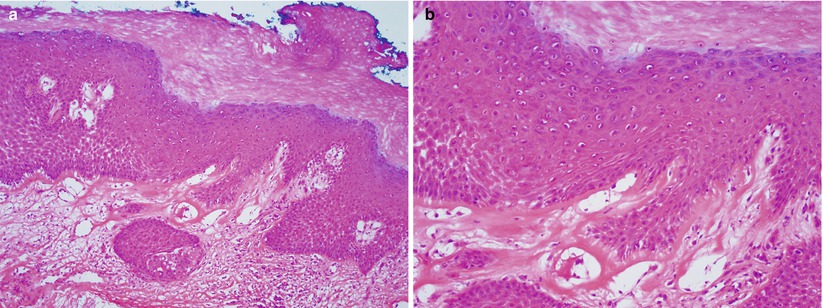

Fig. 2.1

Lichen sclerosus. Hyperkeratotic squamous epithelium with loss of rete pegs at the dermoepidermal junction (a) and presence of eosinophilic homogenization of the subepithelial stroma (b)

Common squamous lesion—a preneoplastic condition to squamous carcinoma that is not associated with human papillomavirus infection.

Grossly shiny, flat to wrinkled vulvar lesion and may be associated with scarring.

Loss of rete pegs leading to flattened epithelial-stromal junction.

Presence of subepithelial homogenization of the stroma and chronic inflammation.

May be associated with hyperkeratosis.

Retained epithelial maturation and polarity without significant cytological atypia.

Differential diagnosis includes lichen planus and stromal fibrosis induced by radiation therapy.

The lesion may be associated with differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN).

Distinction between LS and dVIN may be difficult on frozen section and is typically not critical for intraoperative management.

Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (SIL)/Vulvar and Vaginal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (VIN and VAIN)

Dysplastic squamous epithelium classified into low and high grade dysplasia.

High-grade SIL consists of dysplastic squamous cells involving two-thirds to entire thickness of squamous mucosa (Fig. 2.2).

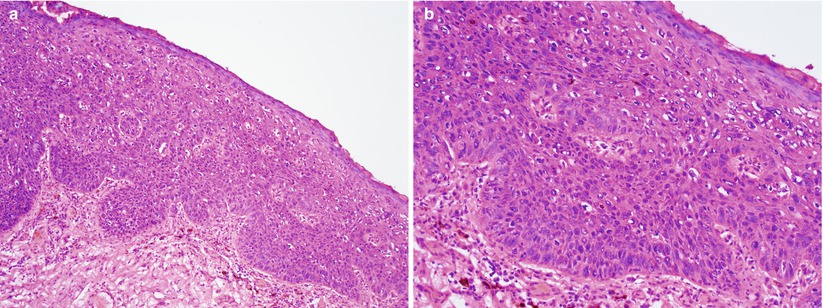

Fig. 2.2

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion/vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 3 (VIN3). Markedly atypical squamous cells involving approximately 2/3 of the squamous epithelium (a) low magnification (b) high magnification

Marked nuclear atypia, loss of polarity, and mitotic activity in the mid and upper third of epithelium—including abnormal mitotic figures.

Absence of stromal invasion.

Usual squamous intraepithelial lesion includes two histological subtypes: warty and basaloid types.

Pagetoid VIN is characterized by singles or clusters of dysplastic squamous cells embedded within non-dysplastic squamous epithelial cells with normal maturation.

Differentiated VIN (dVIN) is commonly seen in postmenopausal patients and may be associated with lichen sclerosus but is unrelated to human papillomavirus infection [2, 3].

Thickened hyperkeratotic squamous epithelium

Elongated and branching rete pegs

Abnormal maturation of individual or groups of squamous cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, prominent desmosomes, and macronucleoli in the mid third of epithelium

Basal and parabasal dysplastic cells with marked cytological atypia

Differential diagnosis

Paget disease

Melanoma

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma

Diagnostic pitfalls/key issues of frozen section diagnosis

Suboptimal orientation and tangential sectioning may mimic invasion.

In case of dVIN, a high index of suspicion is needed to rule out adjacent invasive well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma at the time of frozen section diagnosis, as it is not uncommonly associated with invasion.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) [4–7]

Clinical features

Most often present in postmenopausal patients

Bleeding, dyspareunia, pruritus, and pain

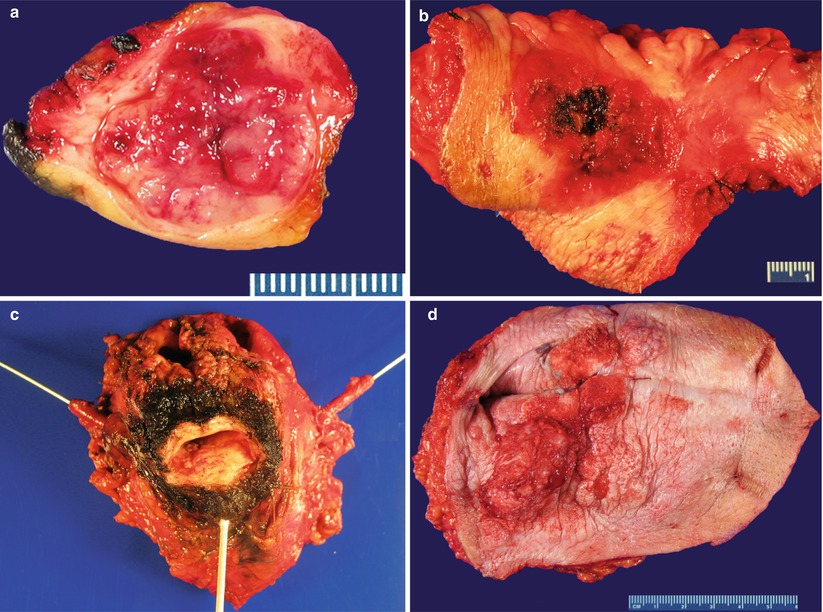

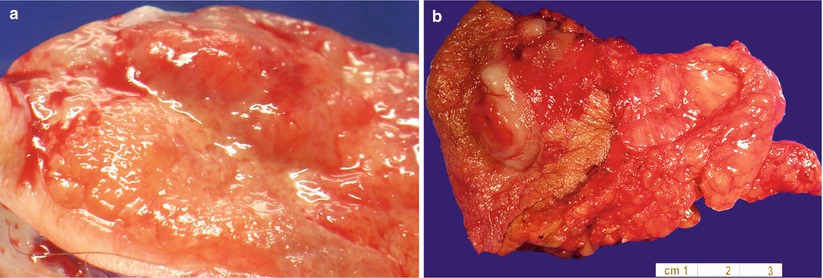

Gross pathology (Fig. 2.3)

Fig. 2.3

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Exophytic masses or plaques with ulcer and hemorrhage involving the vulva (a, b) and vagina (c). Verrucous carcinoma involving the vulva (d)

Most SCCs are located in the posterior and upper third of the vagina and vulvar lesions are often multifocal.

Hyperkeratotic, white, or erythematous plaques to exophytic mass lesions, frequently associated with ulceration.

Microscopic features

Most vaginal squamous cell carcinomas are moderately differentiated and nonkeratinizing, arising in a background of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

Most vulvar squamous cell carcinomas are well differentiated and keratinizing, arising in a background of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, while a smaller proportion of cases are linked to dermatoses or lichen sclerosus.

Sheets, nests, or cords of atypical squamous cells invading stroma with desmoplasia.

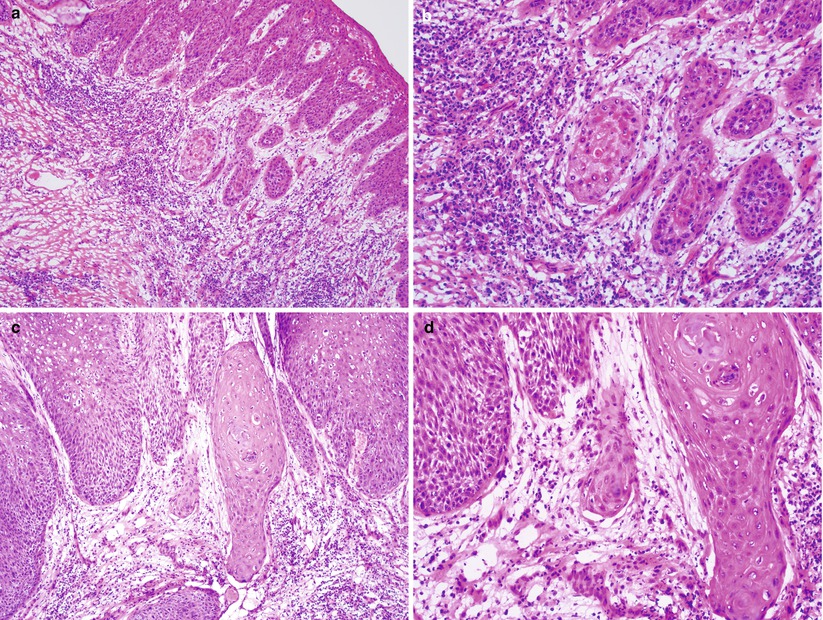

Subtypes of squamous cell carcinoma include keratinizing, basaloid, and warty (Fig. 2.4).

Fig. 2.4

Vulvar invasive squamous cell carcinoma of keratinizing (a, b) and basaloid type (c, d)

Other histological variants include:

Verrucous carcinoma

Pushing border

No significant cytological atypia

No obvious stromal invasion

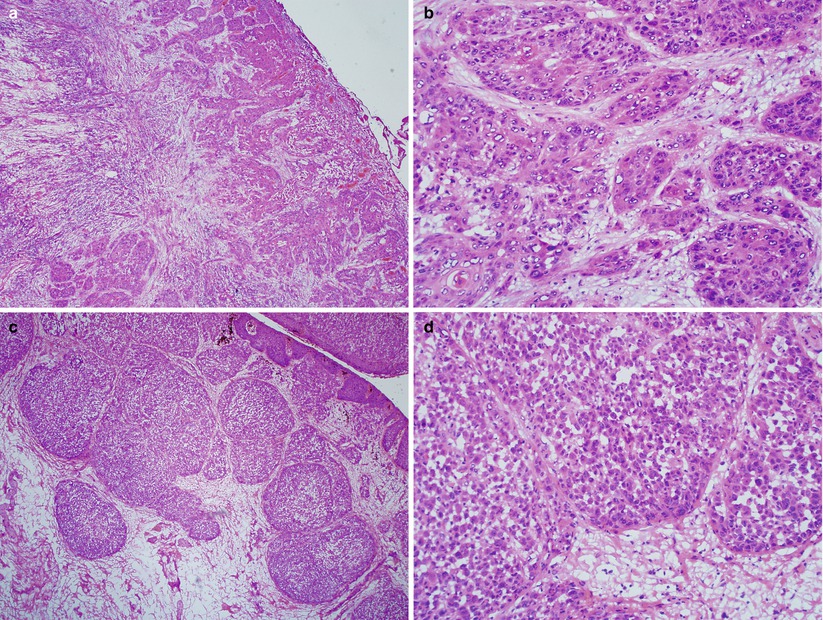

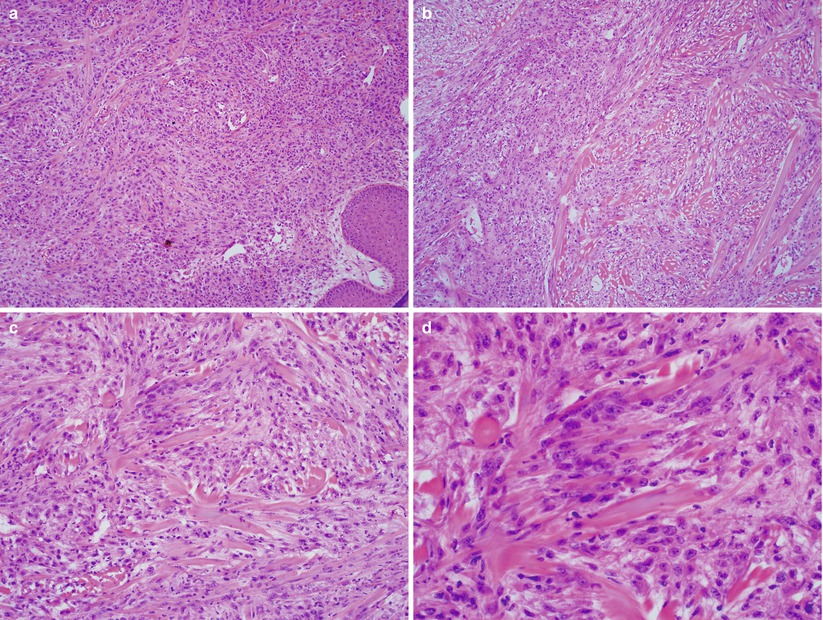

Spindle cell/sarcomatoid SCC (Fig. 2.5)

Fig. 2.5

Vulvar spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma. Spindled squamous cell proliferation simulating mesenchymal sarcoma at various magnifications (a–d)

Spindle cell proliferation

Presence of in situ squamous lesion with focal transition to the spindle component

Must be separated from malignant mixed Mullerian tumor

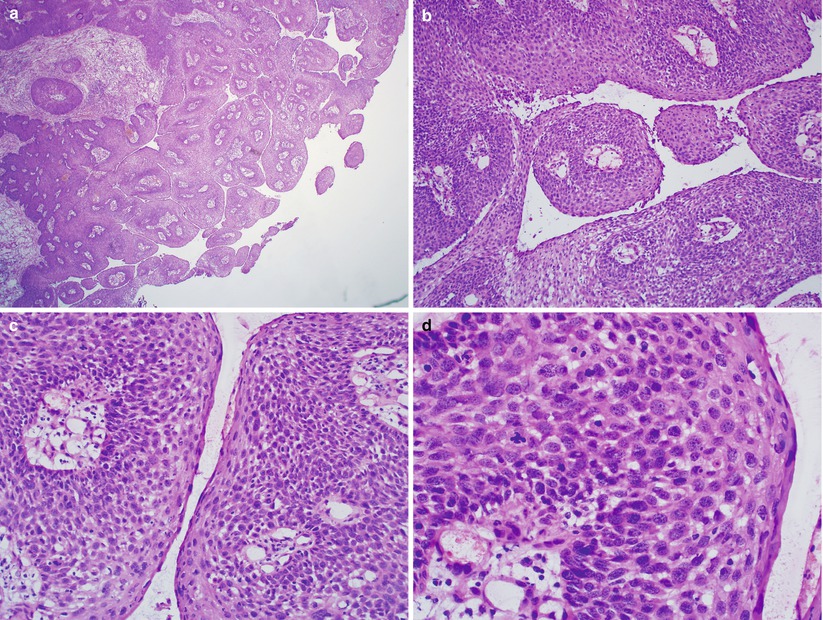

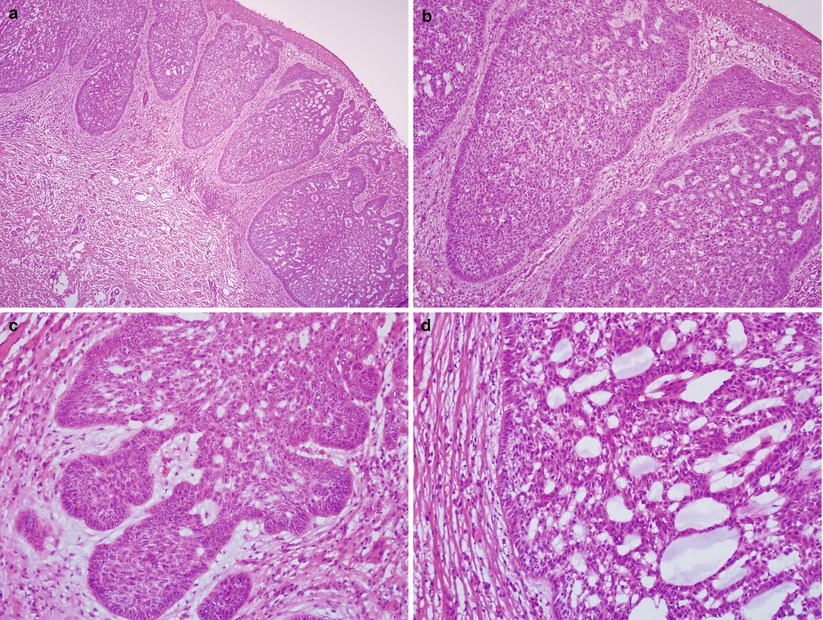

Papillary squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 2.6)

Fig. 2.6

Vulvar papillary squamous cell carcinoma. Papillary proliferation with stromal cores (a, b) composed of high-grade dysplastic squamous cells (c, d)

Surface papillary squamous cell proliferation with stromal cores

High-grade dysplastic squamous cells

May harbor underlying invasive squamous cell carcinoma

Differential diagnosis

HSIL/VIN3.

Vulvar basal cell carcinoma.

Sebaceous carcinoma.

Vulvar granular cell tumor may induce marked pseudoepitheliomatous squamous hyperplasia mimicking squamous cell carcinoma.

Leiomyosarcoma, soft tissue spindle cell sarcomas, and spindle cell melanoma.

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

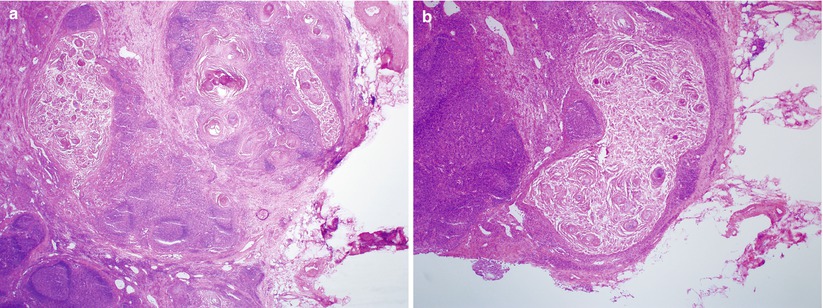

Frozen section evaluation to rule out inguinal lymph node metastasis is common (Fig. 2.7).

Fig. 2.7

Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma with regional lymph node metastasis. Note the marked maturation of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma with cystic appearance (a, b)

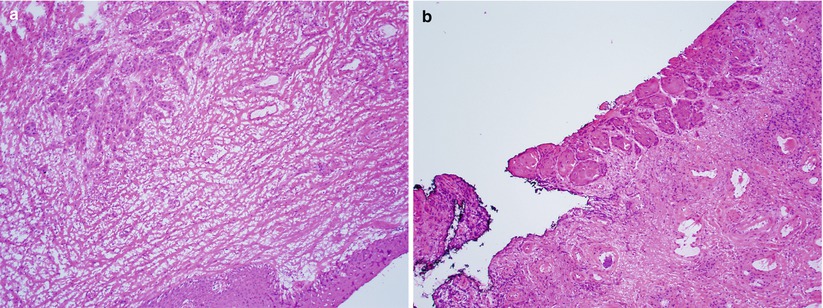

Accurate specimen orientation is crucial for frozen section assessment of surgical margins.

Well-oriented frozen sections help avoiding misinterpretation of tangential sectioning of normal skin structures, squamous hyperplasia, or HSIL/ VIN3/ VAIN3 as invasive squamous carcinoma (Fig. 2.8).

Fig. 2.8

Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma involving surgical margin. Note the microscopic focus of squamous carcinoma involving the stroma of an “en face” section of surgical margin (a) and peripheral mucosal margin (b)

Large sections to include sufficient tumor border are required to appreciate the overall pushing invasive border to separate verrucous carcinoma from condyloma, squamous papilloma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia [8], particularly in association with underlying granular cell tumor.

Careful search for the presence of definite squamous differentiation and absence of junctional in situ melanoma component to confirm spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma as opposed to spindle cell melanoma or spindle cell sarcomas.

Superficially Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Early stromal invasion, less than 1 mm in depth.

Singles or irregular clusters of dysplastic epithelial cells extruding from the base of an in situ lesion.

Isolated tumor nests with paradoxical maturation and haphazard arrangements of tumor cells are highly suggestive of early invasion (Fig. 2.9).

Fig. 2.9

Superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Note detached small atypical squamous nests with characteristic paradoxical maturation and loss of peripheral epithelial palisading beneath the high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion indicating early stromal invasion (a–d)

Stromal response is almost always present, including desmoplasia, edema, and/or lymphoplasmacytic infiltration.

Differential diagnosis includes high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) with pseudoinvasion or tangential sectioning.

Basal Cell Carcinoma [9]

Accounts for 3 % of vulvar cancers.

Most often occurs in elderly patients.

Nodular or plaque lesions (Fig. 2.10), which may be pigmented.

Fig. 2.10

Vulvar basal cell carcinoma. Note the plaque-like (a) and nodular lesions (b)

Nests or sheets of uniform basal cell proliferation with peripheral palisading in solid or adenoid glandular patterns (Fig. 2.11).

Fig. 2.11

Vulvar basal cell carcinoma (adenoid histological subtype). Note the infiltrating nests or sheets of atypical basal cell proliferation (a) with peripheral palisading (b, c) and adenoid glandular pattern (c, d)

Squamous component (metatypical basal carcinoma or basosquamous carcinoma) may be present.

Differential diagnosis includes basaloid squamous cell carcinoma and other skin adnexal tumors.

Intraoperative diagnostic separation from basaloid squamous cell carcinoma is important due to a more aggressive behavior of the latter that may require regional lymph node dissection as part of surgical management.

Basal cell carcinoma should be separated from tangentially sectioned normal hair follicles, particularly at the surgical margin.

Glandular Lesions

Benign Glandular Lesions

Tumorlike Lesions

Bartholin gland hyperplasia: nodular or lobular proliferation of mucinous glands around existing Bartholin duct, frequently associated with cyst formation (Fig. 2.12). Metaplastic changes may occur including squamous metaplasia.

Fig. 2.12

Vulvar Bartholin duct cyst

Vulvar ectopic breast tissue with associated benign conditions (adenosis and papilloma).

Vaginal adenoma (villous and tubulovillous) and vaginal adenosis

Prolapsed fallopian tube occasionally occurs after vaginal hysterectomy and may present as a polypoid lesion at the vaginal vault. Disrupted fallopian tube mucosa, frequently with inflammation, fibrosis, and reactive epithelial changes may simulate infiltrating adenocarcinoma [10].

Vulvar Hidradenoma Papilliferum [11]

Most common benign glandular tumor of the vulva.

Asymptomatic and small (less than 2 cm), frequently involving the labia majora.

Histologically well-circumscribed nodular proliferation of compact glandular or tubular epithelial growth with papillary formations and frequently hyalinized stroma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree