Patient Story

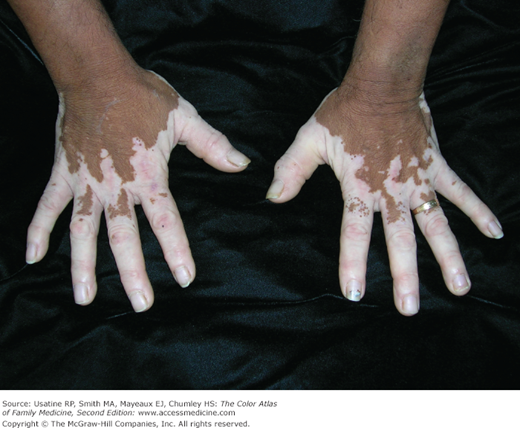

An 8-year-old Hispanic boy is brought in to the clinic by his mother, who is concerned about his pigment loss (Figure 198-1). He is starting to develop this vitiligo around the eyes, and his mother wants him to be treated. The child was started on a topical steroid, and the use of narrow band UVB was discussed if the steroid does not prove helpful. Realistic expectations of the treatments were provided to the mother and her son.

Introduction

Vitiligo is an acquired, progressive loss of pigmentation of the epidermis. The Vitiligo European Task Force defines nonsegmental vitiligo as “an acquired chronic pigmentation disorder characterized by white patches, often symmetrical, which usually increase in size with time, corresponding to a substantial loss of functioning epidermal and sometimes hair follicle melanocytes.”1 Segmental vitiligo is defined similarly except for a unilateral distribution that may totally or partially match a dermatome; occasionally more than one segment is involved.1

Epidemiology

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Autoimmune disease with destruction of melanocytes.

- Genetic component in approximately 30% of cases. Toll-like receptor genes were found to be associated with vitiligo in a population of Turkish patients.4

- Can trigger or worsen with illness, emotional stress, and/or skin trauma (Koebner phenomenon).

Diagnosis

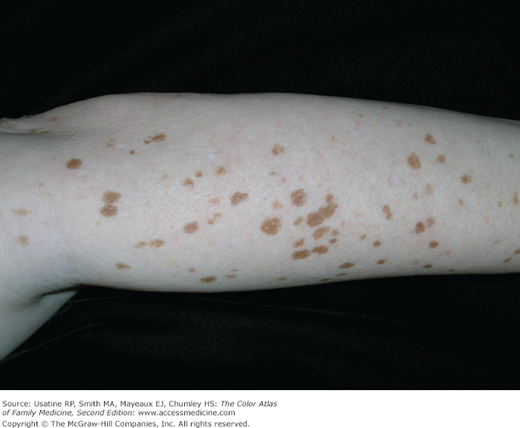

- Macular regions of depigmentation with scalloped, well-defined borders (Figures 198-1, 198-2, and 198-3).

- Depigmented areas often coalesce over time to form larger areas (Figures 198-4 and 198-5).

- Depigmented areas are more susceptible to sunburn. Tanning of the normal surrounding skin makes the depigmented areas more obvious.

- There is no standardized method for assessing vitiligo; strategies include subjective clinical assessment, semiobjective assessment (e.g., Vitiligo Area Scoring Index [VASI] and point-counting methods), macroscopic morphologic assessment (e.g., visual, photographic in natural or UV light, computerized image analysis), micromorphologic assessment (e.g., confocal laser microscopy), and objective assessment (e.g., software-based image analysis, tristimulus colorimetry, spectrophotometry).5 Authors of a literature review concluded that the VASI, the rule of 9, and Wood’s lamp were the best techniques for assessing the degree of pigmentary lesions and measuring the extent and progression of vitiligo.5

- Conditions associated with vitiligo include thyroid disease and the presence of thyroid antibodies,6,7 congenital nevi (in one study, 6.2% vs. 2.8% in those without vitiligo),4 and halo nevi,1 and possibly primary open-angle glaucoma (57% of patients in one case series).8

- Widespread, but generally seen first on the face, hands, arms, and genitalia (Figure 198-6).

- Depigmentation around body openings such as eyes, mouth, umbilicus, and anus is common (Figure 198-7). When the eyelashes are involved it is called leukotrichia.

- Vitiligo can be unilateral or bilateral; in one study, patients with unilateral vitiligo were younger and had an earlier age at onset while those with bilateral vitiligo were more likely to have light skin types and more commonly had associated autoimmune disease.9

- Evaluation for endocrine disorders such as hyper- or hypothyroidism (e.g., thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH]) and diabetes mellitus (e.g., fasting blood sugar) is indicated, as vitiligo can be associated with these disorders.10

- Pernicious anemia and lupus erythematosus should be considered; obtain complete blood count (CBC) with indices and an antinuclear antibody (ANA).

Differential Diagnosis

- Pityriasis alba—Areas of decreased pigmentation with scaling and mild itching. Seen in young children and usually associated with eczema and improves with age (see Chapter 145, Atopic Dermatitis).

- Ash leaf spots—Lance-shaped macules of hypopigmentation, which remain stable in size and shape over time (Figure 198-8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree