Patient Story

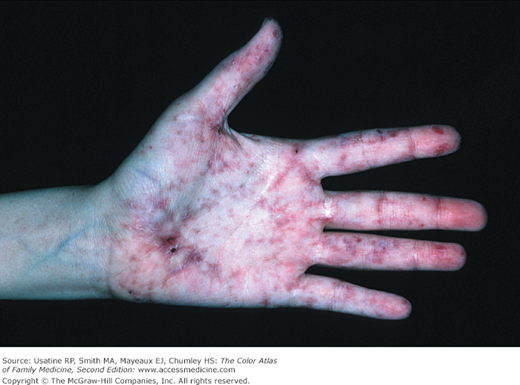

A 21-year-old woman presented with a 3-day history of a painful purpuric rash on her lower extremities (Figure 179-1 and Figure 179-2). The lesions had appeared suddenly, and the patient had experienced no prior similar episodes. The patient had been diagnosed with a case of pharyngitis earlier that week and was given a course of clindamycin. She had not experienced any nausea or vomiting, fever, abdominal cramping, or gross hematuria. Urine dipstick revealed blood in her urine, but no protein. The typical palpable purpura on the legs is consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP).

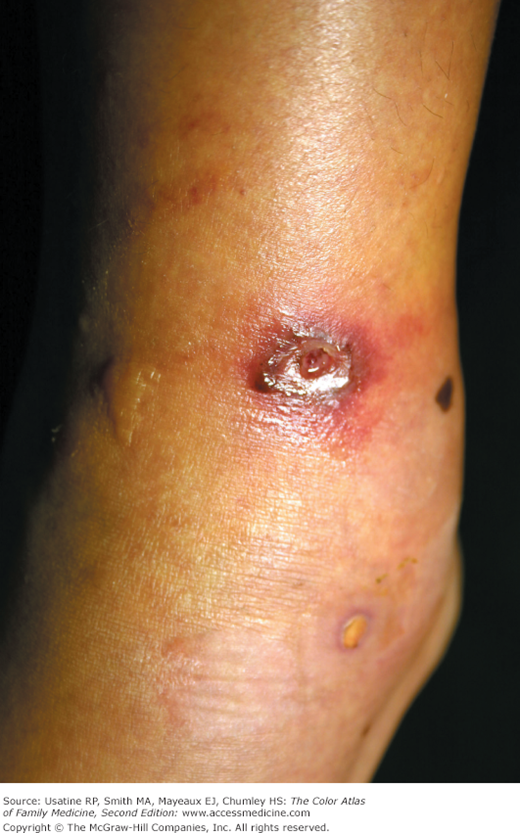

Figure 179-2

Close-up of palpable purpura from the patient in Figure 179-1. Some lesions look like target lesions but this is Henoch-Schönlein purpura and not erythema multiforme. (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Introduction

Vasculitis refers to a group of disorders characterized by inflammation and damage in blood vessel walls. They may be limited to skin or may be a multisystem disorder. Cutaneous vasculitic diseases are classified according to the size (small versus medium to large vessel) and type of blood vessel involved (venule, arteriole, artery, or vein). Small- and medium-size vessels are found in the dermis and deep reticular dermis, respectively. The clinical presentation varies with the intensity of the inflammation, and the size and type of blood vessel involved.1

Synonyms

Epidemiology

- HSP (Figure 179-1, Figure 179-2, and Figure 179-3) occurs mainly in children with an incidence of approximately 1 in 5000 children annually.2 It results from immunoglobulin (Ig) A-containing immune complexes in blood vessel walls in the skin, kidney, and GI tract. HSP is usually benign and self-limiting, and tends to occur in the springtime. A streptococcal or viral upper respiratory infection often precedes the disease by 1 to 3 weeks. Prodromal symptoms include anorexia and fever. Most children with HSP also have joint pain and swelling with the knees and ankles being most commonly involved (Figure 179-3). In half of the cases there are recurrences, typically in the first 3 months. Recurrences are more common in patients with nephritis and are milder than the original episode. To make the diagnosis of HSP, establish the presence of 3 or more of the following:3

- Palpable purpura

- Bowel angina (pain)

- GI bleeding

- Hematuria

- Onset ≤20 years

- No new medications

- Palpable purpura

- Some patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Figure 179-4 and Figure 179-5), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), relapsing polychondritis, and other connective tissue disorders develop an associated necrotizing vasculitis. It most frequently involves the small muscular arteries, arterioles, and venules. The blood vessels can become blocked leading to tissue necrosis (Figure 179-4 and Figure 179-5). The skin and internal organs may be involved.

- Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 179-6, Figure 179-7, and Figure 179-8) is the most commonly seen form of small vessel vasculitis. Prodromal symptoms include fever, malaise, myalgia, and joint pain. The palpable purpura begins as asymptomatic localized areas of cutaneous hemorrhage that become palpable. Few or many discrete lesions are most commonly seen on the lower extremities but may occur on any dependent area. Small lesions itch and are painful, but nodules, ulcers, and bullae may be very painful. Lesions appear in crops, last for 1 to 4 weeks, and may heal with residual scarring and hyperpigmentation. Patients may experience 1 episode (drug reaction or viral infection) or multiple episodes (RA or SLE). The disease is usually self-limited and confined to the skin. To make the diagnosis, look for presence of 3 or more of the following:4

- Age older than 16 years

- Use of a possible offending drug in temporal relation to the symptoms

- Palpable purpura

- Maculopapular rash

- Biopsy of a skin lesion showing neutrophils around an arteriole or venule

- Age older than 16 years

- Systemic manifestations of leukocytoclastic vasculitis may include kidney disease, heart, nervous system, GI tract, lungs, and joint involvement.

Figure 179-3

Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an 11-year-old girl. A. In addition to the palpable purpura, this patient also had abdominal pain. Note how the seam of her jeans is visible in the purpuric pattern. B. She also had knee pain and swelling and was walking with a limp. (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Vasculitis is defined as inflammation of the blood vessel wall. The mechanisms of vascular damage consist of either a humoral response, immune complex deposition, or cell-mediated T-lymphocyte response with granuloma formation.5

- Vasculitis induced injury to blood vessels may lead to increased vascular permeability, vessel weakening, aneurysm formation, hemorrhage, intimal proliferation, and thrombosis that result in obstruction and local ischemia.5

- Small-vessel vasculitis is initiated by hypersensitivity to various antigens (drugs, chemicals, microorganisms, and endogenous antigens), with formation of circulating immune complexes that are deposited in walls of postcapillary venules. The vessel-bound immune complexes activate complement, which attracts polymorphonuclear leukocytes. They damage the walls of small veins by release of lysosomal enzymes. This causes vessel necrosis and local hemorrhage.

- Small-vessel vasculitis most commonly affects the skin and rarely causes serious internal organ dysfunction, except when the kidney is involved. Small-vessel vasculitis is associated with leukocytoclastic vasculitis, HSP, essential mixed cryoglobulinemia, connective tissue diseases or malignancies, serum sickness and serum sickness-like reactions, chronic urticaria, and acute hepatitis B or C infection.

- Hypersensitivity (leukocytoclastic) vasculitis causes acute inflammation and necrosis of venules in the dermis. The term leukocytoclastic vasculitis describes the histologic pattern produced when leukocytes fragment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree