Chapter 16 Vascular diseases

Introduction

The histological features of most forms of vasculitis are not specific for an entity per se. A specific diagnosis requires careful clinical, histological, and serological (i.e. presence of antineutrophil antibodies) correlation.1 The role of the pathologist in evaluating a biopsy is to confirm or deny the presence of vasculitis, and to describe the nature of the inflammatory infiltrate and the type(s) and size(s) of the vessel(s) involved. A histological differential diagnosis is established to guide patient evaluation. Correct biopsy technique and timing are important to allow for adequate assessment for vasculitis. Incisional biopsies to include sufficient subcutis and larger subcutaneous vessels within the first 48 hours after development of the lesion yield the best results.1

The myriad schemata for the classification of the vasculitides are a reflection of the complexity of this controversial class of diseases. Over the last decade or so, several new classifications have emerged that attempt to combine both histological and clinical information (Table 16.1).2 Undoubtedly, these will continue to be refined as a more complete understanding of the pathogenesis of these diseases is gained.

Table 16.1 Types and definitions of vasculitis adopted by the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Systemic Vasculitis*

| Type of vasculitis | Essential components/nonessential components |

|---|---|

| Large vessel vasculitis | |

| Giant cell (temporal) arteritis | Granulomatous arteritis of the aorta and its major branches, with a predilection for the extracranial branches of the carotid artery. Often involves the temporal artery. Usually occurs in patients older than 50 and often is associated with polymyalgia rheumatic. |

| Takayasu arteritis | Granulomatous inflammation of the aorta and its major branches. Usually occurs in patients younger than 50. |

| Medium-sized vessel vasculitis | |

| Polyarteritis nodosa† (classic polyarteritis nodosa) | Necrotizing inflammation of medium-sized or small arteries without glomerulonephritis or vasculitis in arterioles, capillaries, or venules. |

| Kawasaki disease | Arteritis involving large, medium-sized and small arteries, and associated with mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome. Coronary arteries are often involved; aorta and veins may be involved. Usually occurs in children. |

| Small vessel vasculitis | |

| Cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis | Isolated cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis without systemic vasculitis or glomerulonephritis. |

| Henoch–Schönlein purpura | Vasculitis, with IgA-dominant immune deposits, affecting small vessels (i.e. capillaries, venules or arterioles). Typically involves skin, gut, and glomeruli, and is associated with arthralgias or arthritis. |

| Microscopic polyangiitis† (microscopic polyarteritis)‡ | Necrotizing vasculitis, with few or no immune deposits, affecting small vessels (i.e. capillaries, venules or arterioles). Necrotizing arteritis involving small and medium-sized arteries may be present. Necrotizing glomerulonephritis is very common. Pulmonary capillaritis often occurs. |

| Wegener’s granulomatosis‡ | Granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract, and necrotizing vasculitis affecting small to medium-sized vessels (e.g. capillaries, venules, arterioles and arteries). Necrotizing glomerulonephritis is common. |

| Churg-Strauss syndrome‡ | Eosinophil-rich and granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract, and necrotizing vasculitis affecting small to medium-sized vessels, and associated with asthma and eosinophilia. |

| Essential cryoglobulinemic vasculitis | Vasculitis, with cryoglobulin immune deposits, affecting small vessels (i.e. capillaries, venules or arterioles), and associated with cryoglobulins in serum. Skin and glomeruli are often involved. |

* Large vessel refers to the aorta and the largest branches directed toward major body regions (e.g. to the extremities and the head and neck); medium-sized vessel refers to the main visceral arteries (e.g. renal, hepatic, coronary, and mesenteric arteries); small vessel refers to venules, capillaries, arterioles, and the intraparenchymal distal arterial radicals that connect with arterioles. Some small and large vessel vasculitides may involve medium-sized arteries, but large and medium-sized vessel vasculitides do not involve vessels smaller than arteries. Essential components are represented by normal type; italicized type represents usual, but not essential, components.

‡ Strongly associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies.

Reproduced with permission from Jennette, J.C., et al. 1994 Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology, 18, 3–13.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis

Clinical features

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (allergic vasculitis, hypersensitivity vasculitis, leukocytoclastic angiitis) is the commonest form of vasculitis.1–6 It is not a disease entity but represents a vascular reaction pattern due to circulating immune complexes that may either be idiopathic or caused by a number of underlying disorders. The antigens possibly involved are summarized in Table 16.2.1–7 The most frequent associations are drugs in addition to infections.8,9 In over 40% of cases, however, no underlying condition can be identified.10 Although the condition may be limited to the skin, it is important to recognize that it can also be associated with systemic manifestations involving the joints, kidneys, and gastrointestinal system in between 15% and 50% of patients.5,10–12 The disease occurs equally in men and women, and may present in any age group.

Table 16.2 Possible causes of allergic vasculitis

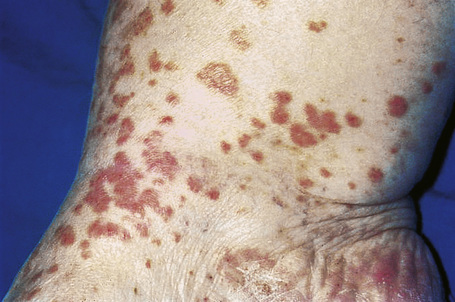

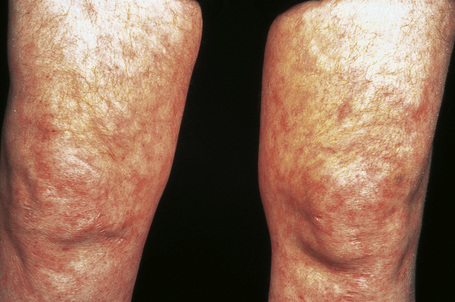

Skin lesions are typically polymorphic, but palpable purpura (nonblanching erythematous papules) is the commonest manifestation (Fig. 16.1). Urticarial, bullous or vesicular, ulceroinfarctive, nodular, pustular, livedoid, and annular lesions may also be encountered (Figs 16.2–16.8).13–17 The lesions measure from 1 mm to several centimeters in diameter. Occasionally, annular erythema multiforme-like lesions occur (Fig. 16.9). The lower legs are affected most often, but lesions can present at a wide variety of sites, including the buttocks, arms, feet, ankles, trunk, and face, particularly in more seriously affected patients (Figs 16.10, 16.11). Lesions may be noted in the skin of dependent areas of bedridden patients, such as the back and buttocks. A frequent accompaniment is edema of the lower legs or ankles (Fig. 16.12). Patients either experience a single occurrence or develop frequent recurrences over months or years. The eruption often occurs in episodes at irregular intervals, each lasting 1–4 weeks. Lesions usually heal completely, although on occasions atrophic scars and hyperpigmentation may occur. Rarely, leukocytoclastic vasculitis shows an erythema gyratum repens gross morphology.18

Fig. 16.2 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: close-up view showing small erythematous lesions.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 16.4 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: here confluent purpura with ulceration is present.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Fig. 16.6 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: Nodular lesions.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 16.7 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: in this patient, there are extensive ulceroinfarctive lesions.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 16.8 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: close-up view of a hemorrhagic blister.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 16.10 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: lesions may be widely disseminated in severely affected patients.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Fig. 16.11 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: this patient has serological evidence of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Although occasional cases are asymptomatic, patients not uncommonly complain of pruritus or burning; less frequently, pain is a feature. Additional features, which are sometimes present, include abdominal pain and gastrointestinal bleeding, joint pains with associated erythema and swelling, and evidence of renal involvement.19 In severe cases, the features resemble acute glomerulonephritis and the nephrotic syndrome may even supervene. Rarely, patients have respiratory involvement (nodular or diffuse infiltrative lesions on X-ray examination), and very exceptionally the central or peripheral nervous system is affected, causing symptoms such as headache, diplopia, and dysphagia.

In one study, drug therapy, often following an upper respiratory tract infection, was the inciting event in 45% of patients.20 Numerous drugs have been implicated as a trigger including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, phenylbutazone), phenytoin, quinidine, amiodarone, potassium iodide, allopurinol, sulfonamides, griseofulvin, penicillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, oxacillin, vancomycin, ofloxacin, clarithromycin, furosemide (frusemide), thiazides, cimetidine, omeprazole, gabapentin, orlistat, zidovudine, indinavir, efavirenz, lisinopril, sotalol, insulin, retinoids, propylthiouracil, thiouracil, mefloquine, methotrexate, azathioprine, sirolimus, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, haloperidol, cytarabine, erlotinib, rituximab, cinacalcet, famciclovir, rifampin, pyrazinamide, insulin aspart, metformin, gold and disulfiram.2,21–63 Levamisole has been described as producing a vasculitis localized to the ears in children. 64, 65 Localized leukocytoclastic vasculitis may occur at the site of interferon alpha injection.66, 67

Collagen vascular disease (most often rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus) is commonly associated with leukocytoclastic vasculitis, 2,68 and in one study it was found in 21% of patients.2 The presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis raises the possibility of associated malignancy.69

Infection is also commonly associated with leukocytoclastic vasculitis, with bacterial, fungal, and viral infection all being implicated.70 Associated bacterial infections include streptococci, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.71–73 Systemic cat scratch disease presenting as leukocytoclastic vasculitis has been documented.74 Hepatitis C infection is a particularly frequent association. It should be noted that hepatitis C is also often associated with cryoglobulins (see section on cryoglobulinemia).75–77

Inflammatory bowel disease, both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, may be coupled with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.78,79 Further rare associations include sarcoidosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, cystic fibrosis, and the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.15,80,81

Physical exercise has also been related to the development of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Outdoor activities in hot weather such as walking, running, and golfing (Golfer’s vasculitis) have especially been implicated and middle-aged to elderly individuals are more frequently affected.82–84 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis rarely represents a paraneoplastic manifestation of an underlying malignancy, especially leukemia and lymphoma.85 Hairy cell leukemia is particularly often associated with leukocytoclastic vasculitis but other forms of vasculitis may also be seen. In one study of 42 patients with hairy cell leukemia and vasculitis, 21 had leukocytoclastic vasculitis and 17 had polyarteritis nodosa.86 In addition, four patients had direct infiltration of vessel walls by leukemic cells (see also section on paraneoplastic vasculitis). Although uncommon, leukocytoclastic vasculitis may also be seen in patients with a variety of solid tumors including non-small cell carcinoma of lung, and adenocarcinoma of breast, colon, prostate, and kidney.87, 88

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be a manifestation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.89 Unusual associations of this condition include the use of a nicotine patch, drug additives, sodium benzoate, protein A column pheresis, interleukin-12 receptor beta-1 deficiency, prolonged exercise, and as a complication of an infected hip prosthesis.90–96

Laboratory investigation may reveal an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), proteinuria or hematuria. In some idiopathic cases and in those associated with systemic disease (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and Sjögren’s syndrome), hypocomplementemia is sometimes evident.5 Urinalysis may reveal proteinuria or hematuria. Cryoglobulins have been found in up to 25% of patients.2 Perinuclear staining antineutrophil antibodies are present in about 20% of patients.2,97

The outcome of leukocytoclastic vasculitis is variable, ranging from a mild, self-limiting illness through to a serious, potentially fatal disorder due particularly to renal involvement.19 About 1.9% of patients die of systemic disease.2 Most patients have a benign outcome. An acute clinical course is seen in approximately 50% of patients.2,10 A chronic course or one characterized by relapses and remissions is seen in some patients.2 In one study of patients with hypersensitivity vasculitis, 54 did not require therapy, 26 were treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and 14 required immunosuppressive agents, most often corticosteroids.20

Pathogenesis and histological features

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is an immune complex-mediated disorder similar to the classic Arthus reaction.98 Immune complexes are deposited in the walls of small blood vessels.5 This is associated with activation of the complement cascade and the production of C5a (a neutrophil polymorph chemotactant). The resultant polymorph influx is associated with release of lysosomal enzymes, including elastases and collagenases, resulting in blood vessel wall damage, fibrin deposition, and the release of red blood cells (purpura) into the perivenular connective tissue. Thrombosis may ensue and, in particularly severe examples, epidermal ischemic damage results. Lesions are particularly seen on the lower legs because of hydrostasis and blood vessel flow sludging.5

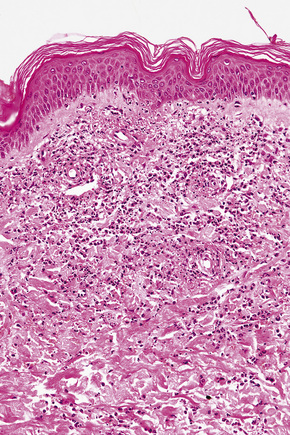

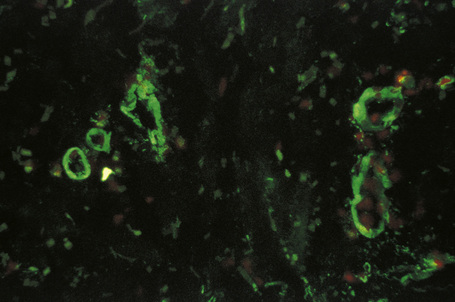

Evidence for an immune complex-mediated pathogenesis is convincing.1 Patients have been clinically proven to have high levels of circulating immune complexes, and these are shown to correlate with vasculitic lesions. Immunoglobulin and complement can be identified in vitro, by immunofluorescence or immunoperoxidase techniques, and in biopsies from blood vessel wall lesions less than 24 hours old (Fig. 16.13).99 Immune complexes can be identified ultrastructurally as clumps of electron-dense material, usually within the basement membrane between endothelial cells and pericytes of postcapillary venules. Examination of apparently uninvolved skin from patients with leukocytoclastic vasculitis sometimes shows immunoglobulin and complement within the walls of dermal blood vessels. If histamine is injected into uninvolved skin 3–4 hours previously, all the features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are evident at biopsy, including neutrophil degeneration; this suggests that the immunoreactants are a cause rather than a consequence of the vasculitis.1

Fig. 16.13 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: IgM is present in the blood vessel walls (direct immunofluorescence).

By courtesy of B. Bhogal, FIMLS, Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

The findings of immunofluorescence studies vary according to the age of the lesion. Immunoglobulins have been described in up to 81% of patients.8 In early lesions, C3 and IgM predominate, in fully developed lesions there is predominance of fibrinogen and IgG, and in late lesions fibrinogen and C3 are detected.8

Some authors, noting that early lesions may contain abundant CD3+, CD4+ and CD1a+ cells, have suggested that cell-mediated immune mechanisms may also play a role in the pathogenesis of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.8 Consistent with this hypothesis is the demonstration of Langerhans cells in the late phase of vasculitis.100 Expression of 72 kD heat shock protein and the presence of gamma/delta T cells in patients with vasculitis associated with infection have led one group of authors to postulate that the cell-mediated immune response plays an important role in that subset.101

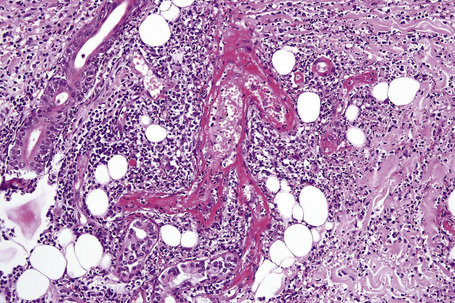

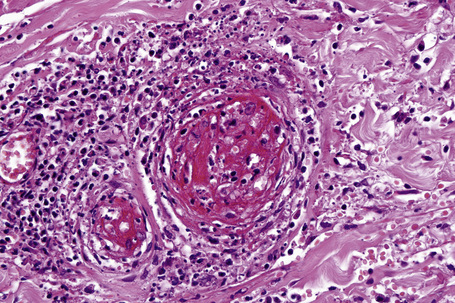

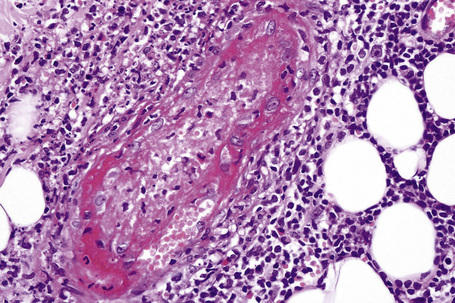

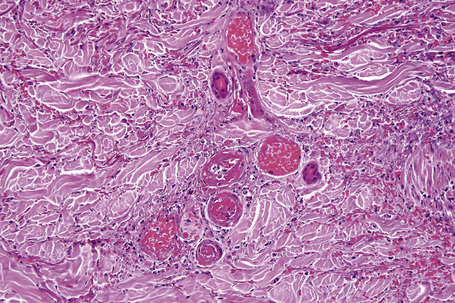

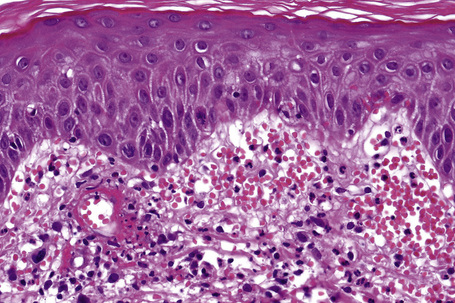

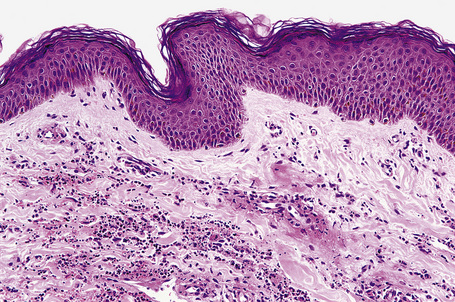

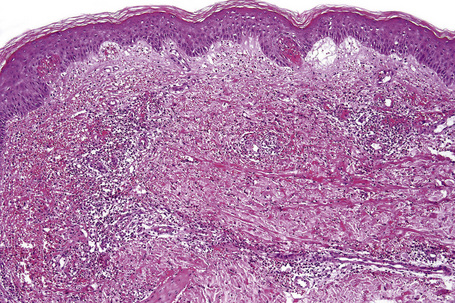

In leukocytoclastic vasculitis, it is the postcapillary venule and the capillary loops (and not the arteriole) which are primarily affected, usually within the superficial dermis (Figs. 16.14, 16.15). In severe cases, particularly those associated with malignancy or connective tissue disease, the inflammatory changes extend into the vasculature of the deep reticular dermis or even the subcutaneous fat.9 The histological features are similar irrespective of the underlying etiology.

The histological features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are those of fibrinoid necrosis associated with endothelial cell swelling and infiltration of the blood vessel walls by neutrophils and conspicuous nuclear dust (Fig. 16.16).2,102,103 Variable numbers of mononuclear cells and eosinophils may be seen. In early lesions, nuclear dust is associated with a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate but multiple tissue sections may be needed to identify fibrinoid vascular changes. The former features, even without unequivocal fibrinoid change, are suggestive of an evolving leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

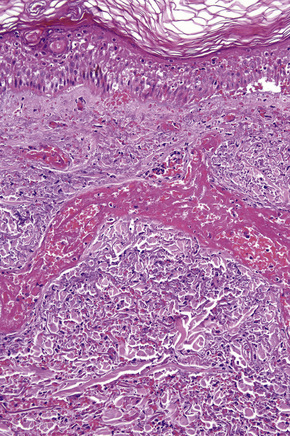

Intravascular thrombi and ischemic necrosis of the overlying epidermis (often with bullae formation) may sometimes be seen (Figs 16.17–16.19). Occasionally, one may encounter intradermal or subepidermal pustules.

Fig. 16.18 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: in this example, there is incipient subepidermal vesiculation.

In patients with associated hypocomplementemia, neutrophils are predominant with far fewer lymphocytes; patients who are normocomplementemic may show lymphocyte predominance. In the surrounding connective tissue, red cell extravasation, edema, and an inflammatory neutrophil infiltrate associated with karyorrhexis (leukocytoclasis) are typically present (Fig. 16.20).

The severity of the histopathological changes in the cutaneous lesions of leukocytoclastic vasculitis does not predict extracutaneous involvement.104

Henoch-Schönlein purpura

Clinical features

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a syndrome characterized by abdominal pain, joint symptoms, and palpable purpura secondary to leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and caused by circulating IgA immune complexes. The disease typically involves children (males more often than females), although adults may also be affected.1–4 Occurrence during pregnancy has only rarely been documented.5 In a large study of children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura, 92% of patients were less than 10 years of age.6

It often complicates an upper respiratory tract infection and is characterized by a seasonal incidence with a peak in winter.1 Clustering of cases has been described, leading one group of authors to postulate that person-to-person spread of an infectious agent plays a role in the pathogenesis of this syndrome.7 Although it may follow a streptococcal throat infection, it sometimes develops after a wide variety of other infective conditions including amebiasis, chickenpox, hepatitis, HIV, yersiniosis, and infection by Toxocara canis, Helicobacter pylori, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and erythrovirus (formerly parvovirus) B19.8–13 Additional causes include adverse reactions to drugs such as ampicillin, penicillin, erythromycin, and clarithromycin.14,15 An association with cocaine inhalation has also been described.16 In one study, drug therapy may have been a precipitating cause in 26% of patients.17

As noted above, classic Henoch-Schönlein purpura is characterized by a triad of purpura, abdominal pain, and arthralgia. The cutaneous clinical findings are those of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutaneous lesions are most frequently the presenting symptom and comprise palpable purpura predominantly affecting the lower limbs, thighs, and buttocks (Fig. 16.21).1,18–20 Targetoid lesions are often present.21 Hemorrhagic bullae are rare.22–24 Subcutaneous nodules have also been documented.25 A prodrome of itchy urticaria is sometimes described.2 Children often have edema, particularly of the feet and lower legs, although it may be more widespread.

In one large study, arthritis was seen in 82% of patients and was the presenting feature in 24%.6 Joint involvement consists of migratory arthralgia predominantly affecting the large joints of the lower limbs. In one study, 37% also had involvement of the upper extremities, with the hand and wrist being more often affected than the elbow.6

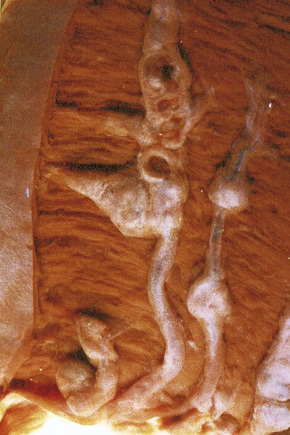

Intestinal involvement with resultant red cell extravasation or hemorrhage leads to abdominal pain and gastrointestinal bleeding. Abdominal pain was noted in 63% of patients in one study of 100 consecutive children presenting with the condition.6 Gastrointestinal disease develops as a consequence of acute vasculitis. Bleeding may be either occult or in the form of bloody or melanotic stools.6 Intussusception is an occasional complication.26,27 Abdominal pain was the presenting complaint in 19% of patients in one study.6 Endoscopy may reveal hemorrhage, ulceration, and erosions.28 IgA is often noted in capillaries of the gastrointestinal tract but frank necrotizing vasculitis was not seen in any patients in two series.28,29 Rarely, gastrointestinal involvement with minimal skin lesions is encountered.30

Renal symptoms are variable and include microscopic hematuria, acute nephritic syndrome, nephrotic syndrome, and acute or chronic renal failure. The pathological features seen on renal biopsy range from mild focal glomerulonephritis to necrotizing or proliferative glomerulonephritis.1,6 In a consecutive series of 100 pediatric patients, a single patient required transplantation.6 Patients older than 7 years are at increased risk of renal involvement.31

Orchitis is a recognized complication of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, affecting 14% of male patients.6,18

Neurological involvement may be manifested by headaches, seizures, mental status changes and, less frequently, ataxia and peripheral neuropathy.32

Low serum C3, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia are rare findings.33

Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children is generally associated with a good prognosis, with less than 2% suffering long-term morbidity.34,35 However, patients do occasionally die from renal failure, gastrointestinal infarction or respiratory involvement. In contrast to pediatric patients, adults are thought to have a worse prognosis. However, one study found that, although older patients had more severe symptoms including frequent renal involvement, prognosis was equally good in young and older patients.36 In another study, complete recovery was seen in 67% of adults after a median follow-up period of 36 months.10 In a further series, a third of patients suffered at least one recurrence of symptoms, usually within a few months of initial presentation.6 Recurrences were also found to be more frequent in patients > 8 years of age and in those with nephritis.18

Solid tumors including breast cancer and hematological malignancy have been associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura.37–41 One study found that nearly a third of adults with Henoch-Schönlein purpura had an associated tumor.37 For this reason, the authors concluded that physicians should suspect an underlying malignancy in older patients (especially males of 40 years or more) with Henoch-Schönlein purpura.38

Pulmonary hemorrhage is a rare complication that may prove fatal.42,43

Pathogenesis and histological features

An incomplete picture of the pathogenesis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura has emerged. As noted above, it seems a wide variety of infective agents may trigger this disease. Henoch-Schönlein purpura is associated with IgA deposition in blood vessel walls, both in the dermis and in the renal glomerulus (mesangium). IgA1 is the major IgA subclass found in the cutaneous blood vessels.44 Fibrinogen and C3 are also usually present. Raised levels of serum IgA and IgE are present in some, but not all, patients.6 IgA antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and IgA anticardiolipin antibodies have also been documented.45,46 There is evidence that patients have an increased number of IgA-type B cells.47 More recently, IgA-binding regions from streptococcal M proteins have been identified in a significant subset of skin and renal biopsies from patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura.48

The finding of IgA deposition by immunofluorescence is not equivalent to a diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. A vasculitis with the presence of IgA deposition in patients lacking other typical features of Henoch-Schönlein purpura has been described in association with cancer, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and inflammatory bowel disease.49

The observation of an association between DRB1*01 and DRB1*11 and Henoch-Schönlein purpura suggests a genetic susceptibility in some patients.50,51 Other authors have suggested that DQA1*0301 and C4 deletion may also represent risk factors for IgA nephropathy as well as Henoch-Schönlein nephritis.52

Biopsies of cutaneous lesions show features of typical leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Fig. 16.22).

Differential diagnosis

The histological differential diagnosis includes other forms of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Since IgA deposition can be seen in the blood vessel walls of patients with leukocytoclastic vasculitis but without evidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, this finding is not diagnostic in isolation.53 In one study, only 24% of patients with vascular IgA deposition had Henoch-Schönlein purpura.53 Careful clinical correlation is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

Infantile acute hemorrhagic edema

Clinical features

Infantile hemorrhagic edema is a form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis that is mostly seen in newborns but has also been described in the first 3 years of life and occasionally in older children.1–11 The disease is usually limited to the skin but mucosal involvement may be an additional feature.10 Transient renal involvement with microscopic hematuria and proteinemia, hypocomplementemia, abdominal pain, and elevated transaminases are exceptional additional findings.12,13 It frequently follows vaccination or infection including otitis, upper respiratory tract infection or conjunctivitis.1,10,11 An association with cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus-1 or rotavirus infection has been documented.14–16 Since many children had received antibiotics for infection prior to development of lesions, a subset of cases may represent reaction to medication.1 This disease has a peak incidence in the winter months.

Skin lesions are widely distributed, and often involve the head and neck, and limbs. They present as purpuric lesions that often have a rosette or targetoid configuration.2,3 The cheeks and ears seem to be sites of predilection.3,11 Resolution within a few weeks is typical and recurrences are not reported.1,11,17

Pathogenesis and histological features

The pathogenesis of infantile hemorrhagic edema is unknown; however, it is likely that the disease is immune mediated. Biopsy shows features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis with variable fibrinoid necrosis.3

Differential diagnosis

Some authors consider infantile hemorrhagic edema to be a variant of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Others do not agree, arguing that the absence of perivascular IgA on immunofluorescence staining, absence of systemic involvement in most patients, and the benign clinical course do not support this view.3,18 However, a very interesting hypothesis possibly linking the two diseases has been postulated.19 Goraya and Kaur note that, since the IgA immune system in infants is immature, if acute hemorrhagic edema were related to Henoch-Schönlein purpura, the patient would be incapable of mounting an IgA-mediated immune response and this would explain the lack of IgA on immunofluorescence studies in the majority of patients.19 Clearly, further study of this disorder is necessary to elucidate its pathogenesis and to clarify its nosological position in the classification of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Urticarial vasculitis

Clinical features

Urticarial vasculitis is an uncommon condition characterized clinically by urticaria and histologically by leukocytoclastic venulitis.1–5 In addition to urticarial skin lesions, patients may also experience angioedema, arthralgia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and evidence of renal involvement.6,7 The term encompasses a spectrum of illness, with some patients experiencing only mild symptoms while others develop serious systemic involvement.7,8

Urticarial vasculitis is most often seen in the third to fifth decades and shows a female predominance.7 The cutaneous lesions are urticarial in appearance, consisting of edematous, raised, erythematous plaques associated with nonblanchable purpura (Figs 16.23, 16.24). However, in contrast to uncomplicated urticaria, cutaneous lesions of urticarial vasculitis often last 24–72 hours.9 Patients commonly complain of pruritus, burning or pain. The frequency of cutaneous symptoms varies considerably, from daily to monthly.

Fig. 16.24 Urticarial vasculitis: close-up view.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Joint pain, stiffness, and swelling, particularly of the hands, elbows, feet, ankles, and knees, are seen; however, frank arthritis is extremely rare.10 Hypocomplementemia, which correlates with systemic involvement, is a feature in many patients.4,7,8,11,12 Proteinuria and hematuria may also be noted. Rarely, patients develop focal or diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis. Crescentic glomerulonephritis, mesangial glomerulonephritis, and membranous nephropathy have also been documented.8,13–16 Gastrointestinal symptoms can include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, and an associated peripheral neuropathy has been reported.17

The ESR is raised in many patients with hypocomplementemia. There may also be depression of the early classic pathway components C1q, C4 and C2. Patients with hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis have a high prevalence of autoantibodies to endothelial cells.18,19

Schnitzler’s syndrome is a term that has been applied to patients with urticarial vasculitis and monoclonal IgM gammopathy.20–25 Hepatosplenomegaly, elevated ESR, and white blood cell count, fever and joint pain are characteristic features.21–23 An associated monoclonal IgA gammopathy has been reported and an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder is present in some patients.20,26,27

Importantly, urticarial vasculitis (especially the hypocomplementemic variant) is often associated with, or heralds the onset of, a variety of systemic diseases, including SLE, arthritis, interstitial lung disease, pericarditis, mixed connective tissue disease, systemic sclerosis, relapsing polychondritis, hepatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, serum sickness, polyarteritis nodosa and Wegener’s granulomatosis, viral infection, Sjögren’s syndrome, cryoglobulinemia, polycythemia rubra vera, reaction to drugs (including cocaine and diltiazem), and as a response to sunlight.8,13,28–38 The condition may be exacerbated by methotrexate.39 In one study, more than 50% of patients had uveitis, scleritis, conjunctivitis or episcleritis.8 It appears that patients with hypocomplementemia have more severe disease.28 Some authors have postulated that hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis represents a subset of SLE. Others, however, have failed to confirm this observation.8,40

Urticarial vasculitis has been documented in association with malignancy.8,41 Given the rarity of this association, this may well be coincidental. Nevertheless, a diagnosis of urticarial vasculitis should always initiate an evaluation for possible underlying disease. Urticarial vasculitis usually has a benign outcome.8

Pathogenesis and histological features

In many patients, no underlying cause is discovered. In others, antibody–antigen complexes (a type III hypersensitivity reaction) is implicated.4,5

The vasculitis affects the superficial vascular plexus and is characterized by a leukocytoclastic pattern (Fig. 16.25). Extravasation of red blood cells is evidence of vascular damage. A background of dermal edema may be seen. Often, the histological features are subtle and are easily overlooked, with only focal fibrinoid vascular change, few neutrophils, and sparse karyorrhexis. In our experience, the vasculitis is usually low grade or subtle in nature; however, more impressive necrotizing vasculitis is seen in some patients. Others have shown that endothelial necrosis is unusual.5

In summary, urticarial vasculitis may show a spectrum of histological changes ranging from urticaria with very mild vascular injury to frank necrotizing vasculitis.42

Polyarteritis nodosa and microscopic polyangiitis

Classic polyarteritis nodosa (Kussmaul-Maier disease) is a rare systemic vasculitis involving medium-sized and small arteries.1 Some view the disorder not as a disease sui generis but, less restrictively, as a syndrome with many triggering causes and disease associations. Classic polyarteritis nodosa overlaps both clinically and histologically with microscopic polyangiitis (microscopic polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyarteritis). Distinction between these entities may be difficult and criteria for their distinction are controversial. Nevertheless, they seem to represent distinctive syndromes that warrant separate classification to facilitate appropriate treatment.2 In order to maintain a usable working classification, we – while admitting they are separate diseases – prefer to describe them in the same section to facilitate comparisons between them.

Clinical features

Classical polyarteritis nodosa

Classic polyarteritis nodosa is a multisystem disease with protean clinical manifestations (Table 16.3).1,3–5 It should be noted that the 1990 criteria from the American College of Rheumatology do not distinguish polyarteritis nodosa from microscopic polyarteritis. However, in the more recent Chapel Hill nomenclature this discrimination is made (see Table 16.1). Polyarteritis nodosa is associated with significant morbidity and mortality even when treated with corticosteroids. With therapy, survival is in the range of 75–80%.1 Although a wide age group may be affected, patients are most often in their fifth or sixth decade.6 There is a male predilection (4:1). Patients commonly present with constitutional symptoms including weight loss, pyrexia, and anorexia.1

Table 16.3 1990 criteria for the classification of polyarteritis nodosa (traditional format)*

| Criterion | Definition |

|---|---|

| Weight loss ≥ 4 kg | Loss of 4 kg or more of body weight since illness began not due to dieting or other factors |

| Livedo reticularis | Mottled reticular pattern over the skin of portions of the extremities or torso |

| Testicular pain or tenderness | Pain or tenderness of the testicles not due to infection, trauma or other causes |

| Myalgias, weakness, or leg tenderness | Diffuse myalgias (excluding shoulder and hip girdle) or weakness of muscles or tenderness of leg muscles |

| Mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy | Development of mononeuropathy, multiple mononeuropathies or polyneuropathy |

| Diastolic BP > 9 mmHg | Development of hypertension with the diastolic BP higher than 90 mmHg |

| Elevated BUN or creatinine | Elevation of BUN > 40 mg/dL or creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL not due to dehydration or obstruction |

| Hepatitis B virus | Presence of hepatitis B surface antigen or antibody in serum |

| Arteriographic abnormality | Arteriogram showing aneurysms or occlusions of the vesical arteries not due to arteriosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia, or other non-inflammatory causes |

| Biopsy of small or medium-sized artery | Histological changes showing the presence of granylocytes or granulocytes and mononuclear leukocytes containing PMN in the artery wall |

The presence of any three or more criteria yields a sensitivity of 82.2% and a specificity of 86.6%.

BP, blood pressure; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophils.

* For classification purposes, a patient shall be said to have polyarteritis nodosa if at least three of these 10 criteria are present.

Reproduced with permission from Lightfoot, D.W. (1991) Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 3, 3–7.

Cutaneous lesions are common and are present in over 40% of patients.6–10 Palpable purpuric lesions and foci of ulceration, particularly involving the lower limbs, are most often found (Figs 16.26–16.28).10 Livedo reticularis is also a common cutaneous manifestation (Fig. 16.29). Cutaneous nodules may also be seen. A maculopapular rash, vesiculation, and pustular lesions are occasional features (Figs 16.30–16.33).

Fig. 16.27 Polyarteritis nodosa: this patient presented with large hemorrhagic lesions on the legs.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 16.28 Polyarteritis nodosa: epidermal infarction has resulted in these digital ulcers.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Fig. 16.29 Polyarteritis nodosa: this patient shows florid livedo reticularis.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 16.30 Polyarteritis nodosa: erythematous macules are occasionally seen.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 16.31 Polyarteritis nodosa: erythematous papules are present around this patient’s ankles.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 16.32 Polyarteritis nodosa: this patient presented with acral erythematous lesions.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Both peripheral and central nervous system involvement are often encountered. The former presents as sensory neuropathies (numbness or paresthesias), motor neuropathies (wrist or foot drop) and combined sensorimotor lesions (mononeuritis multiplex and polyneuropathy). Central nervous system involvement may present as confusion, disorientation or delirium. Eye involvement is a rare feature of polyarteritis nodosa.11 Complications include choroidal infarction, ischemic optic neuropathy, retinal artery occlusion, episcleritis, ulcerative keratitis, uveitis, and orbital pseudotumor.11–13

Gastrointestinal involvement is also an important cause of morbidity and mortality.14,15 Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Serious complications include gastrointestinal hemorrhage, perforation, and infarction, the last being a not uncommon cause of death. Involvement of the hepatobiliary tract may also be seen.16,17 Involvement of the gallbladder and pancreas has also been reported and can represent an incidental finding or patients may present with symptoms of acute cholecystitis.18,19

Cardiac manifestations include pericarditis, arrhythmias, and myocardial infarction due to coronary artery involvement (Fig. 16.34). Although it is often stated that polyarteritis nodosa does not involve the lung, in exceptional cases pulmonary involvement is seen and patients occasionally complain of asthma, hemoptysis, and effusions. Although clinical involvement of the lungs is rare, autopsy evaluation has shown that arteritis affecting the bronchial arteries is not uncommon, being seen in 70% in one small series.20

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree