Vascular Compression of the Duodenum

Stanley W. Ashley

Matthew T. Menard

Compression of the duodenum between the vertebral column and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is a relatively rare clinical condition. Known by a wide variety of names since first reported, in recent decades it has been termed “vascular compression of the duodenum,” a designation which most accurately reflects the anatomic basis for the disorder. Associated symptoms are those typical of intestinal obstruction, and the onset is often insidious and marked by the gradual appearance of nausea and vomiting. In the appropriate clinical setting, the diagnosis is made on the basis of characteristic computed tomographic (CT) findings. The syndrome may follow weight loss, prolonged immobilization in bed, and various operative procedures, but has also been reported to occur spontaneously. Treatment most often involves surgical decompression in the form of division of the ligament of Treitz and a duodenojejunostomy, with generally favorable outcomes.

History

The Austrian anatomist Carl Von Rokitansky, rumored to have performed over 30,000 autopsies over the course of his pioneering career, first described constriction of the third portion of the duodenum by the overlying SMA in 1942. Kundrat subsequently postulated the root of the mesentery to be the anatomic structure responsible for partial obstruction of the duodenum, whereas the German physician Albrecht believed that mesenteric traction was the etiology of the constrictive problem. In the early 20th century, there was recognition of the frequent association with gastric dilatation and suggestion that duodenal stasis and dilation were causative factors in such patients. In 1907, Bloodgood described several cases of gastromesenteric ileus and was the first to propose that surgical decompression in the form of a duodenojejunostomy might be an effective treatment. One year later, Slavely reported the first such procedure.

Since Von Rokitansky’s landmark observation, interest in this clinical entity has been variable, and for periods of time, its validity has been questioned by the reigning medical establishment. This lack of full acceptance was in large part due to a poor understanding of the pathophysiology of the condition. Specifically, a distinction between duodenal stasis and mechanical obstruction was often not made, leading to inconsistent treatment results. For example, for a period in the early 1900s, both resection of the colon and plication of the mesentery were tried in an effort to relieve mesenteric compression. Others described a gastropyloroduodenojejunostomy as a means of decompressing persistent gastric distension following duodenojejunostomy.

Reports by Kellogg and Wilkie in the late 1920s helped establish duodenojejunostomy as the surgical treatment of choice. In one of the larger published series, Wilkie described 75 patients with duodenal obstruction treated with a 6% operative mortality rate. He also identified a subset of patients who had a poor response to the procedure in whom it was less clear that a mesenteric source of compression was responsible. In subsequent years, as the indications for operative decompression were liberalized and the treatment was more widely applied, overall outcomes were noted to be less favorable. A resurgence of interest in this problem in the 1960’s was attributed to a comprehensive review of the available literature by Barner and Sherman. A number of further publications that helped clarify the anatomic basis and elucidated additional clinical features of the syndrome also served to reinforce its legitimacy. Today, it is perceived by most to be a true clinical entity. The numerous names by which vascular compression of the duodenum has been referred to over the years, some of which continue on occasion to be utilized, are listed in Table 1.

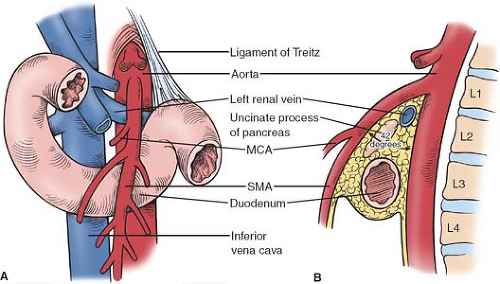

The duodenum, so named as it was considered to be equal in length to the width of 12 fingers, is most susceptible to compression by the overlying SMA within its horizontally oriented third portion. This segment of the duodenum typically crosses the vertebral column at the lower portion of the third lumbar and/or upper portion of the fourth lumbar vertebra. Notably, the fourth vertebra is the most anterior part of the spinal column. The duodenum is fixed at three anatomic points: the pylorus, the peritoneum of the second and third portions of the peritoneum, and the ligament of Treitz.

The SMA typically arises from the anterior aorta at the level of the lower aspect of the first lumbar vertebra. A significant degree of variation of this takeoff point has been noted; however, with the origin reported to range from the 12th thoracic to the third lumbar vertebra. Though the average angle formed by the SMA and the aorta was found to be 42 degree in one autopsy series, there is also considerable variability in this measurement; the angle as reported in the literature ranges between 18 and 70 degree. Inside this angle lies the left renal vein, the uncinate process of the pancreas, the third portion of the duodenum, and a retroperitoneal fat pad that typically encircles the SMA (see Fig. 1).

Table 1 Historical Names for Vascular Compression of the Duodenum | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

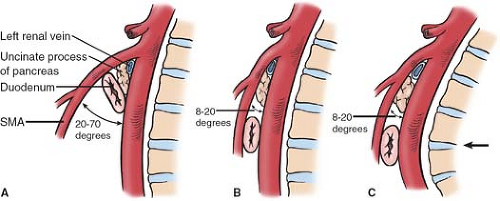

A markedly narrowed aortomesenteric angle is a hallmark diagnostic finding in patients with vascular compression of the duodenum (see Fig. 2). Lukes et al. found this angle to be as low as 8 degree in their review, whereas other authors have reported the aortomesenteric angle to range from 6 to 40 degree in patients with radiographic evidence of compression. Lukes et al. also reported a significantly reduced distance from the origin of the SMA to the midpoint of the duodenum, known as the aortomesenteric distance, with involved patients having an average distance of only 3.3 mm compared to a distance of 18 mm in control patients. Aberrancies of the normal anatomic pattern of the SMA and its branches in relation to the duodenum (see Fig. 3) and the ligament of Treitz (Fig. 4) have also been implicated in the described clinical syndrome. In particular, the patients in whom the duodenum crosses the vertebrae at the

fourth lumbar vertebrae where the lumbar curvature is at its most pronounced anteriorly are at elevated risk of developing obstructive problems (Fig. 2C).

fourth lumbar vertebrae where the lumbar curvature is at its most pronounced anteriorly are at elevated risk of developing obstructive problems (Fig. 2C).

The long recognized association of rapid weight loss with the syndrome is believed to be a result of loss of the mesenteric and retroperitoneal fat in this anatomic region that further serves to reduce both the aortomesenteric angle and distance. Additional anatomic aberrancies that have been linked to a smaller angle between the SMA and aorta include an abnormally low origin of the SMA, excessive lumbar lordosis, a foreshortened or hypertrophied ligament of Treitz, and an unusually high fixation point of the ligament of Treitz. Of note, a zone of elevated pressure preceding one of reduced pressure has been noted in the distal duodenum in normal subjects assessed with manometry. This intriguing finding suggests an anatomic and physiologic basis for a possible predisposition to a functional duodenal obstruction that remains to be further elucidated.

The predominant clinical symptoms present in patients with vascular compression of the duodenum are that of nausea, vomiting, and postprandial abdominal pain centered at the epigastrium. These symptoms can be episodic or constant, and, if persistent, dehydration and/or weight loss is common. In fact, associated mortality secondary to dehydration, cachexia, and aspiration following emesis have all been described. Patients are typically young, and there is a predominance of female versus male patients. As mentioned, an asthenic body habitus is also frequently present in the patients with vascular compression of the duodenum, and it has long been noted that concomitant weight loss often precedes the onset of other symptoms. The anatomic considerations detailed above provide one rationale for how antecedent rapid weight loss is thought to lead to the development of the syndrome.

Though nearly half of the patients with vascular compression of the duodenum have no obvious clinical trigger and therefore would be considered idiopathic, Akin et al. identified supine immobilization, scoliosis, and the placement of a body cast in addition to weight loss as predisposing conditions to syndrome development. The so-called “cast syndrome” was first described in 1950 by Dorph to characterize the patients in whom placement of a whole body cast precipitated the subsequent onset of intractable nausea and vomiting with accompanying gastric and duodenal dilatation. The majority of the reported cases were in young patients, many of whom were being treated for scoliosis. Removal of the cast, rehydration with intravenous fluids, and nasogastric decompression usually led to resolution of symptoms. Some authors later reported successful management of this problem with the institution of total parenteral nutrition, whereas others noted recovery only with surgical decompression.

Vascular compression of the duodenum has also been reported in other disease states associated with significant weight loss, including anorexia nervosa, severe combat injury leading to a prolonged bedridden status, and major burns. In one report of burn patients, all patients had a >30% total body surface area burn and the syndrome developed soon after the burn injury. Associated symptoms of aspiration, gastroduodenal ulceration, and sepsis were common. Though some patients had symptomatic relief with positional maneuvers, the best results were achieved with operative decompression. Prone positioning was more successful in relieving duodenal compressive symptoms in a number of patients rendered bedridden following severe combat injuries.

Isolated descriptions of a similar compressive symptom complex that have followed total proctocolectomy and J-pouch anal anastomosis have been attributed to traction on the mesentery by the translocated terminal ileum. Finally, vascular compression of the duodenum has also been described in the pediatric population. Though it has typically been seen in this setting in those having experienced either rapid weight loss or rapid growth, it has also been reported in those with age-appropriate weight and height.

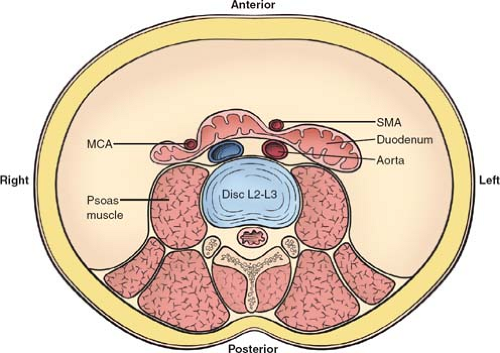

Fig. 3. Axial view at the level of the second to third lumbar vertebrae shows the potential points of obstruction of the third portion of the duodenum between the SMA and the aorta, or the MCA and right psoas muscle. SMA, superior mesenteric artery; MCA, middle colic artery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|