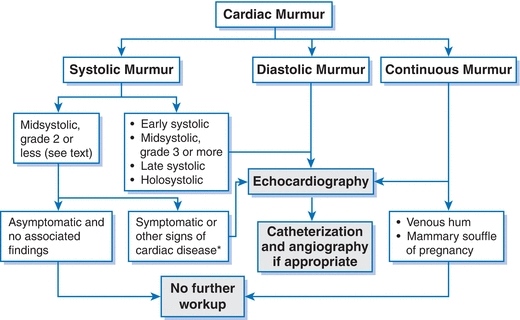

Figure 9-1 Evaluation of heart murmurs. (Modified from Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. 2008 Focused Update Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:e1–e142.)

Aortic Stenosis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Aortic stenosis (AS) is usually present for many years before patients become symptomatic.

- There is a long latency with an excellent prognosis until chest pain, syncope, or heart failure develops.

- The operative mortality of isolated aortic valve replacement (AVR) is quite low in patients with isolated AS, normal left ventricular (LV) function, and relatively few comorbidities (<2% in experienced centers).1

- Treatment of high-risk and inoperable patients has been modified with the introduction of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Pathophysiology

- AS results from an active valvular biology that leads to valve fibrosis and calcification; it occurs in 2% to 7% of patients >65 years of age.

- A bicuspid aortic valve occurs in 1% to 2% of the population and is associated with severe calcific AS at an earlier age (50s to 60s). It accounts for about 50% of valve replacements for AS.

- Maintenance of cardiac output in AS imposes a pressure overload on the LV, which leads to hypertrophic remodeling, diastolic dysfunction, increased myocardial oxygen demand, increased filling pressures, and eventually systolic dysfunction.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- Generally, until the AS becomes severe, patients will not have symptoms directly attributable to the valve abnormality. Many patients with severe AS will be asymptomatic. Providers should be alert to the common scenario in which affected elderly patients subconsciously reduce activity and therefore report no symptoms.

- With the development of symptoms (e.g., angina, dizziness, syncope, heart failure), it is critical that these patients be seen and offered valve replacement expeditiously as the mean survival is 2 to 3 years for symptomatic severe AS.

- Risk factors for faster progression or a worse outcome include an elevated brain natriuretic peptide, abnormal exercise test, increased valve calcification, rapid increase in transvalvular gradient, higher transvalvular gradient, increased LV hypertrophic remodeling, diastolic dysfunction, and pulmonary hypertension.

Physical Examination

- The physical examination will reveal a harsh crescendo-decrescendo murmur heard over the aortic area and often radiating to the carotids.

- As the severity increases, the murmur peaks later and the aortic second sound (A2) becomes softer.

- The carotid upstroke becomes weaker and is delayed as the significance of AS increases (pulsus parvus et tardus).

Diagnostic Testing

Electrocardiography

- Electrocardiogram often reveals LV hypertrophy with strain.

Imaging

- Echocardiography:

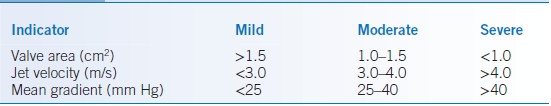

- The development of quantitative Doppler echocardiography has revolutionized the care of these patients. The aortic valve area (AVA) and the peak jet across the valve can now be determined with accuracy (Table 9-1).

TABLE 9-1 Severity of Aortic Stenosis

Modified from Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. 2008 Focused Update Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:e1–e142.

- Any patient with a significant murmur (≥grade 3) in the aortic region should undergo echocardiography.

- Exercise testing may be beneficial in asymptomatic patients to unmask symptoms and further risk-stratify patients.

- Patients with an AVA <1 cm2 but low gradients due to low flow and low ejection fraction (EF) benefit from a dobutamine echocardiogram to clarify the severity of the AS and assess for contractile reserve.

- The development of quantitative Doppler echocardiography has revolutionized the care of these patients. The aortic valve area (AVA) and the peak jet across the valve can now be determined with accuracy (Table 9-1).

- Cardiac MRI: Detection of myocardial fibrosis by MRI has been associated with increased mortality in patients with AS and may be helpful in risk stratification.

- Cardiac catheterization: Because of the high prevalence of coronary disease in patients with AS, all patients with chest pain and/or planned AVR should undergo coronary angiography.

TREATMENT

Medications

- There is no medical therapy specifically targeting AS that has been shown to improve clinical outcomes.

- It is important to treat any associated cardiovascular comorbidities (hypertension, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure) with appropriate medical therapy.

- In particular, hypertension is quite common in patients with AS and often undertreated due to concerns about inducing hypotension. Inadequately treated hypertension adds an additional detrimental load on the LV beyond the valvular stenosis.

Surgical Management

- AVR is the definitive treatment for AS and improves survival and quality of life, even in very elderly patients (>80 years of age).

- AVR is indicated for symptomatic patients with severe AS, asymptomatic patients with an EF < 50%, or those with moderate or severe AS undergoing cardiac surgery for another reason.

Percutaneous Management

- TAVR is a rapidly evolving, less invasive therapeutic alternative to surgical AVR for patients with severe AS.

- Patients at high risk or ineligible for surgical AVR may be candidates for TAVR. They should be evaluated by a multidisciplinary heart team (cardiologist, cardiac surgeon) to determine the best management strategy.

- The PARTNER Trial showed that TAVR is noninferior to surgical AVR in high-risk patients and TAVR is superior to standard therapy in inoperable patients.2

- Additional trials to evaluate these techniques are underway as are ongoing device modifications.

MONITORING/FOLLOW-UP

- In patients with AS, the AVA decreases 0.1 cm2/year on average, but there is significant variability from patient to patient in the rate of progression.

- Echocardiography is recommended every 3 years for mild AS, every 1 to 2 years for moderate AS, and at least yearly for severe AS.

- Patients with severe AS should be seen at least every 6 months to monitor clinically for the development of symptoms.

Aortic Regurgitation

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Pathophysiology

- Mild aortic regurgitation (AR) is frequently documented by Doppler echocardiography, but severe AR requiring operative therapy is relatively uncommon.

- AR can result from intrinsic valve disease (e.g., bicuspid aortic valve, rheumatic heart disease, endocarditis, trauma, lupus, and other connective tissue disease).

- Dilatation of the aortic root can also cause severe AR (e.g., Marfan syndrome, aortic dissection, long-standing hypertension, ankylosing spondylitis, and syphilitic aortitis).

- Severe acute AR leads to marked increase in LV pressure since the LV is not compliant enough to accommodate the regurgitant volume. This may lead to pulmonary edema and/or cardiogenic shock.

- Since severe AR usually develops over years, the LV is allowed to dilate and accommodate the large regurgitant volume and maintain normal LV pressures. Over time, these compensatory mechanisms fail and the LV becomes markedly dilated, systolic function diminishes, and LV pressures increase.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- Patients with acute severe AR are almost always symptomatic and often critically ill.

- Patients with chronic severe AR may be asymptomatic for years (compensated state) before developing symptoms, which are most commonly fatigue, dyspnea on exertion, palpitations, and heart failure.

Physical Examination

- Physical examination reveals bounding pulses, a wide pulse pressure, displaced PMI, and a diastolic decrescendo murmur often heard with the patient sitting up or bending forward.

- An Austin-Flint murmur can sometimes be heard at the apex as a low-pitch diastolic murmur due to regurgitant flow through the aortic valve that impedes opening of the anterior mitral valve leaflet and obstructs flow through the mitral valve.

Diagnostic Testing

Electrocardiography

- Electrocardiogram reveals LV hypertrophy and often left atrial enlargement.

Imaging

- Any patient with a diastolic murmur should undergo echocardiography.

- The echocardiogram should document the severity of AR, whether the valve is bicuspid, the size of the LV in systole and diastole, and the size of the aortic root.

- Transesophageal echo may be helpful to clarify whether there is a bicuspid valve and more accurately measure the dimension of the aorta.

TREATMENT

Medications

- Hypertension should be treated in patients with severe AR according to established guidelines.

- In the absence of hypertension, vasodilators may be considered as a chronic treatment for patients with symptomatic severe AR and reduced EF when surgery is not recommended or asymptomatic patients with severe AR and LV dilation with normal EF.

- Vasodilators may also be used in the acute setting in patients with severe HF symptoms as a bridge to AVR.

Surgical Management

- AVR is indicated for symptomatic patients with severe AR and for asymptomatic patients with EF <50% or severe LV dilatation (LV end-systolic dimension >50 to 55 mm; LV end-diastolic dimension >70 to 75 mm).

- Operative mortality is generally quite low and should be strongly considered even if the EF is markedly reduced.

- Concomitant surgery to repair/replace the aortic root is indicated in patients with an aortic root >4.5 to 5.0 cm with a bicuspid aortic valve or Marfan syndrome or >5.0 to 5.5 cm in the absence of those conditions. Operative therapy is also indicated for an increase of 0.5 cm/year in the aortic diameter.

MONITORING/FOLLOW-UP

- Patients with mild-to-moderate AR should be followed yearly with an echocardiogram performed every 2 to 3 years.

- Severe AR with normal LV function should be monitored clinically every 6 months with an echo usually once a year.

- Any change in symptoms warrants immediate evaluation.

- First-degree relatives of patients with Marfan syndrome or a bicuspid aortic valve should be screened with imaging.

Mitral Stenosis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Etiology

- Rheumatic heart disease is the most common cause of mitral stenosis (MS), particularly in young women. Mean age for severe MS is the fifth to sixth decades of life.

- With the decrease in rheumatic heart disease, the prevalence of MS has dropped dramatically in developed countries.

- Other causes of MS are rare (e.g., congenital) or less often progress to severe MS (e.g., mitral annular calcification).

Pathophysiology

- Leaflet and subvalvular thickening and calcification results in a decrease in the mitral valve orifice and the development of a diastolic transmitral pressure gradient.

- The transmitral pressure gradient depends on the severity of the obstruction (mitral valve area), flow across the valve (cardiac output), diastolic filling time (heart rate), and the presence of effective atrial contraction.

- Significant MS can lead to elevation of left atrial, pulmonary venous, and pulmonary artery pressures, which can lead to pulmonary vascular remodeling and right ventricular dysfunction.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- The latency or delay between rheumatic fever and significant MS is typically decades; symptom onset can be insidious.

- In addition to dyspnea and/or fatigue, patients may present with cough and sometimes hemoptysis; symptoms of right heart failure may also occur.

- Symptoms may develop suddenly in the setting of fever, new-onset atrial arrhythmia, hyperthyroidism, or pregnancy due to an increased transvalvular gradient.

- Thirty to forty percent of patients with MS develop an atrial arrhythmia.

Physical Examination

- Physical examination reveals a loud S1 and an opening snap in diastole followed by a middiastolic rumble heard best at the apex with the bell of a stethoscope with the patient in left lateral decubitus position.

- A right ventricular heave, loud P2, and/or signs of right heart failure may also be present.

Diagnostic Testing

Electrocardiography

- Electrocardiogram often shows left atrial enlargement and right ventricular hypertrophy.

Imaging

- Echocardiography can frequently quantify the severity of MS (transvalvular gradient, valve area) and consequences of MS (elevated pulmonary pressures, MR, left atrial enlargement, right ventricular dysfunction).

- Stress echocardiography can be helpful in some cases to assess transmitral gradient and pulmonary artery pressures during exercise.

- If valvuloplasty is considered, transesophageal echocardiography should be performed to evaluate for any associated mitral regurgitation, left atrial clot, and significant calcification/tethering of the mitral valve and subvalvular apparatus.

TREATMENT

Medications

- Therapy is primarily aimed at rate control and prevention of thromboembolism.

- β-Blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCBs) tend to be more effective than digoxin for tachycardia associated with exertion.

- Anticoagulation is indicated for atrial arrhythmia (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent), prior embolic event (even in sinus rhythm), and left atrial thrombus.

- Rhythm control strategies often fail in patients with significant MS.

Percutaneous Management

- Patients with moderate or severe MS with symptoms or associated pulmonary hypertension (at rest or with exercise) should be considered for percutaneous or surgical intervention.

- Patients with rheumatic MS are potentially candidates for percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty (PMBV), whereas patients with calcific MS are not.

- Based on transesophageal echocardiography, patients with extensive calcification/fusion of the mitral leaflets and/or subvalvular apparatus, moderate or greater mitral regurgitation, or left atrial clot are not candidates for PMBV.

- PMBV is the procedure of choice in patients with rheumatic MS without these exclusions; these patients generally have an excellent result from PMBV that may last several years.

Surgical Management

- Those patients needing an intervention on their valve who are not candidates for PMBV should generally undergo valve replacement; valve repair is rarely an option for fibrotic, calcified valves.

MONITORING/FOLLOW-UP

- Asymptomatic patients with moderate to severe MS should be evaluated clinically every 6 months with an echo at least yearly or as clinically indicated.

- In asymptomatic patients, consideration should be given to performing periodic exercise stress tests to evaluate for exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension.

- Holter monitor should be considered in patients with palpitations to monitor for atrial arrhythmias.

Degenerative Mitral Regurgitation

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Etiology

- Degenerative mitral valve disease refers to those processes that affect the mitral valve leading to regurgitation (myxomatous degeneration, mitral valve prolapse, rheumatic disease, and endocarditis).

- Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) occurs in 1% to 2% of the population and is characterized by prolapse of one or both mitral valve leaflets into the left atrium >2 mm in midsystole.

Pathophysiology

- In patients with acute severe MR (e.g., endocarditis, torn chordae), the sudden large-volume load from the ventricle into a noncompliant left atrium leads to increased pressures that are transmitted to the pulmonary vasculature, causing pulmonary congestion and edema. Forward cardiac output is reduced, and there is compensatory tachycardia to attempt to maintain forward flow.

- As the severity of chronic MR worsens over time, LV function can be maintained and the increased volume load accommodated at normal filling pressures by LV dilation and eccentric hypertrophy.

- As compensatory mechanisms fail, the LV and LA progressively dilate, LV dysfunction occurs, and atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension can develop.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- Patients with acute severe MR can present suddenly and be critically ill.

- Many patients with chronic severe MR are asymptomatic before they present with subtle dyspnea on exertion and fatigue.

- Patients may symptomatically decompensate with the development of atrial fibrillation.

Physical Examination

- Physical examination reveals a holosystolic murmur radiating to the axilla. Prolapse of the posterior and anterior leaflets may produce radiation of the murmur to the chest wall or back, respectively.

- A murmur may not be audible in the setting of acute severe MR, but does not rule out the diagnosis.

Diagnostic Testing

Electrocardiography

- Electrocardiogram may reveal left atrial enlargement and LV hypertrophy; in more end-stage cases, right ventricular hypertrophy may be present.

Imaging

- Chest radiography may reveal cardiomegaly, left atrial enlargement, and pulmonary vascular redistribution.

- Echocardiography:

- Transthoracic echocardiography should be used to evaluate the severity of mitral regurgitation, mechanism of leak, LV dimensions and function, left atrial size, and pulmonary artery pressures. It is important to incorporate quantitative measurements of MR severity, particularly in those with moderate or severe MR.

- Exercise stress evaluation with an echocardiogram should be considered to clarify whether symptoms are present in patients with severe MR and/or to evaluate for exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension.

- Transesophageal echocardiogram should be performed to clarify the severity and mechanism of the MR and assess the feasibility of valve repair.

- Transthoracic echocardiography should be used to evaluate the severity of mitral regurgitation, mechanism of leak, LV dimensions and function, left atrial size, and pulmonary artery pressures. It is important to incorporate quantitative measurements of MR severity, particularly in those with moderate or severe MR.

TREATMENT

Medications

- There are no medical therapies that have been demonstrated to improve clinical outcomes (e.g., delay the time to surgery) in patients with degenerative MR and normal LV function.

- Treat other cardiovascular comorbidities (e.g., hypertension and coronary artery disease) according to appropriate guidelines.

- Patients with severe acute MR may be bridged to definitive therapy (valve surgery) with vasodilators or a balloon pump to maximize forward flow and minimize pulmonary congestion.

- Patients with MVP with a history of TIAs should take ASA (75 to 325 mg), and those with palpitations should avoid/minimize the use of tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine as these may worsen symptoms.

Surgical Management

- Acute severe MR must be treated promptly with surgery.

- For chronic severe MR, surgery is indicated for symptoms or, in the absence of symptoms, when there is LV dilation (LV end-systolic dimension ≥4 cm) or EF <60%. Surgery should also be considered in asymptomatic patients with the onset of an atrial arrhythmia and pulmonary hypertension (resting or exercise induced) or when the likelihood of successful valve repair is >90%.

- Mitral valve repair is preferable to mitral valve replacement for degenerative mitral valve disease and should be performed by a high-volume valve repair surgeon.

- Patients with a concomitant atrial arrhythmia should be considered for a surgical maze procedure at the time of valve repair.

MONITORING/FOLLOW-UP

- Patients with severe MR should be monitored very closely for the onset of symptoms, LV dysfunction, LV dilation, atrial arrhythmia, or pulmonary hypertension.

- Echocardiography should be done every 1 to 2 years in patients with moderate MR and at least yearly in those with severe MR. Periodic assessment for exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension is also recommended.

Functional Mitral Regurgitation

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Functional MR may occur in patients with LV dysfunction and dilation. The regurgitation results from annular dilatation and papillary muscle displacement due to LV enlargement and remodeling, which causes tenting of the leaflets and inadequate coaptation.

- It may occur in the setting of nonischemic or ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy.

- Functional MR often leads to more severe regurgitation (MR begets MR) as the increased volume load leads to further adverse LV remodeling and dilation, more leaflet tenting, and more inadequate coaptation.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- Patients have a history of LV dysfunction and often a history of myocardial infarction and/or heart failure preceding the development of MR.

- Patients with moderate to severe functional MR usually have an audible holosystolic murmur heard best at the apex radiating to the axilla; when LV dysfunction is severe, the murmur may be relatively soft.

Diagnostic Testing

Electrocardiography

- Electrocardiogram may reveal left atrial enlargement, LV enlargement, atrial arrhythmia, right ventricular hypertrophy, and/or pathologic Q waves depending on the severity and chronicity of disease and etiology of LV dysfunction.

Imaging

- Chest radiography may reveal cardiomegaly, left atrial enlargement, and pulmonary vascular redistribution.

- Transthoracic echocardiography should be used to evaluate the severity of mitral regurgitation, mechanism of leak, severity of leaflet tethering, LV dimensions and function, and pulmonary artery pressures. It is important to incorporate quantitative measurements of MR severity, particularly in those with moderate or severe MR.

TREATMENT

Medications

- Patients with functional MR have LV dysfunction, so treatment with all the medications indicated for LV dysfunction and heart failure is appropriate for these patients, including ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, diuretics, and cardiac resynchronization therapy.

- These therapies can lead to favorable reverse remodeling of the LV, which can reduce the severity of functional MR.

Surgical Management

- Whether and when to perform mitral valve surgery for patients with functional MR is controversial as there is conflicting evidence regarding the presence of any survival and/or quality-of-life benefit from surgical intervention.

- Unlike surgery for degenerative MR, it is not clear whether valve repair or replacement is preferable for functional MR.

Percutaneous Management

- A variety of devices are being developed and investigated as potentially less invasive alternatives to surgery for the reduction of functional MR.

- The mitral clip has been evaluated in the EVEREST Trial, and ongoing clinical trials are testing it in patients with functional MR who are at increased operative risk.

Endocarditis Prophylaxis

- In 2007, the American Heart Association (AHA) released its most recent guidelines regarding infective endocarditis (IE) prophylaxis; it contains major changes compared with prior guidelines.3 There is a notable lack of data supporting the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in the setting of dental, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary procedures, and evidence of causation is circumstantial. The guidelines suggest that there be greater emphasis on oral health in individuals with high-risk cardiac conditions.

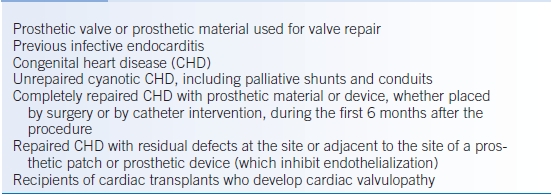

- The guidelines conclude that antibiotic prophylaxis is reasonable in a few clinical situations. Prophylaxis is now recommended only for patients undergoing certain dental procedures with cardiac conditions associated with the highest risk of adverse outcome (Table 9-2).

TABLE 9-2 Cardiac Conditions with the Highest Risk of Adverse Outcome from Infective Endocarditis

Modified from Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007;116:1736–1754.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree