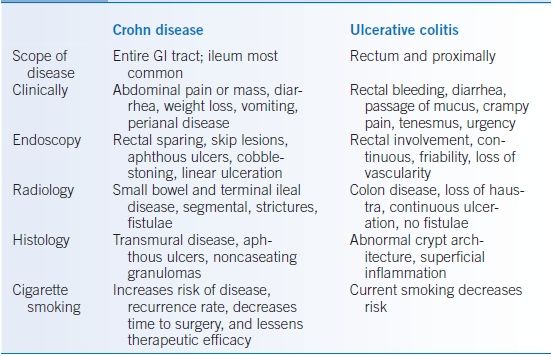

TABLE 31-2 Comparison of Crohn Disease and Ulcerative Colitis

Modified from Iskandar H, Ciorba MA. Inflammatory bowel disease. In: Gyawali CP, ed. The Washington Manual Gastroenterology Subspecialty Consult, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012:169–179.

Epidemiology

- IBD can develop at any age; peak incidence rates occur between 15 and 30 years of age.

- Though all races are affected, the incidence rates are higher in white Northern Europeans and North Americans.

- The prevalence of IBD in the United States is4

- CD: 58 to 241/100,000

- UC: 34 to 263/100,000

- CD: 58 to 241/100,000

Risk Factors

- Patients with a first-degree relative with IBD have an increased risk of having IBD themselves.

- Current smokers have a lower risk of developing UC. Former smokers, however, have a 1.7-fold increased risk for UC over lifetime nonsmokers.

- Smoking is associated with an increased risk of CD, increased chance of disease recurrence, and reduced therapeutic efficacy.

- Though no single microbe causes IBD, concomitant infections (intestinal and extraintestinal) as well as antibiotic use can exacerbate IBD.

Associated Conditions

- IBD can be associated with extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs), which often correlate to colonic IBD activity.5 EIMs occur more frequently in UC than CD.

- Musculoskeletal

- Central arthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis and sacroiliitis) associated with IBD are progressive conditions and tend to correlate poorly with IBD activity.

- Pauciarticular peripheral arthritis correlates well with colonic inflammation. Asymmetric large joint (knees, hips, ankles, wrists, and elbows) involvement is typical.

- Polyarticular peripheral arthritis is symmetric, involves smaller joints (fingers and toes), and may occur independent of IBD activity.

- Osteoporosis risk is increased in IBD patients presumably due to cumulative steroid use, malabsorption, low body weight, and relative hypogonadism related to disease activity. Guidelines suggest using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) testing to screen for osteoporosis in all postmenopausal women with IBD and those individuals who have received prolonged or frequent courses of corticosteroids. All patients with disease severe enough to require steroids at least once should take supplemental vitamin D (800 IU) daily along with 1,000 to 1,500 mg calcium supplementation.

- Central arthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis and sacroiliitis) associated with IBD are progressive conditions and tend to correlate poorly with IBD activity.

- Dermatologic

- Erythema nodosum (EN) is a painful, poorly demarcated, nodular lesion that tends to be bilateral but asymmetric. It is closely related to IBD activity, and treatment of the underlying disease resolves EN lesions.

- Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a debilitating skin disease characterized by irregular, blue-red ulcers with purulent necrotic bases. Lesions are usually found on the lower extremities, buttocks, abdomen, and face. PG can develop independent of IBD activity. A high index of suspicion for PG should exist for patients with poorly healing skin lesions.

- Aphthous ulcers in the oropharynx occur in 10% to 30% of patients with IBD.

- Erythema nodosum (EN) is a painful, poorly demarcated, nodular lesion that tends to be bilateral but asymmetric. It is closely related to IBD activity, and treatment of the underlying disease resolves EN lesions.

- Ocular

- Episcleritis is a painless inflammation of the eye’s surface. Visual acuity is not affected, and episodes tend to coincide with IBD flares.

- Uveitis is an inflammation of the eye that can be painful and associated with decreased visual acuity. It does not always coincide with disease activity. Uncontrolled uveitis can cause permanent ocular damage.

- Prompt referral to an eye specialist is necessary for all new changes in vision or eye complaints in the setting of IBD.

- Episcleritis is a painless inflammation of the eye’s surface. Visual acuity is not affected, and episodes tend to coincide with IBD flares.

- Hepatobiliary

- Gallstones may develop in patients with CD due to malabsorption of bile salts in the ileum.

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is more commonly associated with UC than CD and is a chronic inflammatory disease of the bile ducts (refer to Chapter 30). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) reveals strictures of intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts. Patients with PSC have an increased risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma and colitis-associated cancer.

- Gallstones may develop in patients with CD due to malabsorption of bile salts in the ileum.

- Vascular: The risk of venous and arterial thrombosis is increased in patients with IBD and can be a major source of mortality.

- Renal: Nephrolithiasis (calcium oxalate stones) can occur with CD. Hyperoxaluria is common and related to fat malabsorption, which increases the amount of dietary oxalate available for absorption in the colon.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- A thorough history is the first step in diagnosing IBD and defining disease severity.

- Questions should be aimed at abdominal symptoms, systemic signs of toxicity, family history of IBD, medication history, smoking history, and the presence of EIMs.

- UC primarily presents with bloody diarrhea, urgency, tenesmus, and abdominal pain.

- CD patients primarily present with abdominal pain, weight loss, fatigue, and sometimes fever. Diarrhea and rectal bleeding are less common than in UC, but can be significant.

Physical Examination

- Fever, hypotension, and tachycardia are signs of systemic toxicity.

- High-pitched or absent bowel sounds may suggest obstruction.

- Peritoneal signs (rebound, guarding, and rigidity) suggest intestinal perforation.

- A right lower quadrant mass is often palpable in patients with active ileal CD.

- A careful rectal and perianal examination is important. Skin tags, fistulae, and anal fissures suggest perianal CD.

- With toxic megacolon, the colon rapidly dilates to >5 to 6 cm and the abdomen is distended and painful. As the name implies, patients appear quite toxic (e.g., fever, hypotension, and tachycardia). Steroids may mask some of these signs.

- Ocular, skin, and musculoskeletal exams identify EIMs of IBD.

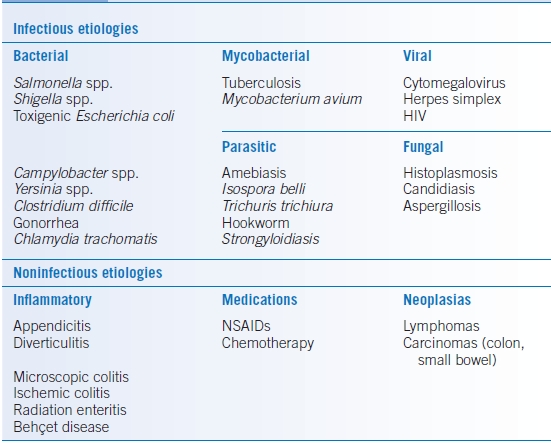

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of IBD is extensive, including infection, neoplasia, ischemia, and other inflammatory conditions (Table 31-3).

TABLE 31-3 Differential Diagnosis for Irritable Bowel Disease

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Modified from Iskandar H, Ciorba MA. Inflammatory bowel disease. In: Gyawali CP, ed. The Washington Manual Gastroenterology Subspecialty Consult, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012:169–179.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree