Vagotomy: Truncal and Highly Selective

Mary T. Hawn

George A. Sarosi Jr.

Ashley Augspurger Davis

DEFINITION

Truncal vagotomy is defined as the division of the anterior and posterior vagus nerves, which innervate the stomach and remainder of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, at the level of the distal esophagus. Vagotomy eliminates cholinergic stimulation to gastric parietal cells and decreases parietal cell response to gastrin and histamine, thereby reducing gastric acid secretion. By transecting at the entrance point into the abdomen, all innervation to the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and small intestine is also divided. Truncal vagotomy requires a drainage procedure due to the disruption of antral and pyloric muscular innervation.

For many years, vagotomy was one of the cornerstones of surgical treatment of ulcers. However, with further understanding of the role of Helicobacter pylori in ulcer pathogenesis and advancement in pharmacologic management including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine blockers, the role of surgery has changed. Of the classic indications for ulcer, surgery, bleeding, perforation, obstruction, and intractability, vagotomy is only commonly used in those patients who require surgical control of ulcer bleeding.

Level one evidence suggests that it is not necessary in the treatment of duodenal perforation in patients who are H. pylori positive,1 and the number of patients requiring operation for gastric outlet obstruction and intractability has declined dramatically with the advent of improved pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy of peptic ulcer disease (PUD). The incidence of definitive acid reduction surgery decreased by more than 50% from 1993 to 2006.2

Highly selective vagotomy (HSV) is defined as the division of the gastric branches of the nerves of Latarjet. The nerves of Latarjet, celiac division of posterior vagus, and hepatic division of anterior vagus are preserved. Therefore, cholinergic stimulation is selectively eliminated to reduce acid secretion by parietal cells in the body and fundus, and the innervation of the antrum and pylorus, biliary tract, and small and large intestines are untouched. A drainage procedure is not required with HSV. This is also known as “parietal cell vagotomy” or “proximal gastric vagotomy.”

The operation was developed to avoid the need for a gastric drainage procedure, which is required with truncal vagotomy, as up to one-third of patients will develop delayed gastric emptying following this procedure. Despite the elegance of parietal cell vagotomy, it is a technically demanding operation with a higher ulcer recurrence rate and much longer learning curve than truncal vagotomy. In an era when few vagotomies are performed, it has largely fallen out of favor.3

Of historical note, a selective vagotomy sections the anterior vagus just distal to the point where the branch to the gallbladder and liver and the posterior vagus just distal to the branch to the pancreas and small intestines. Although in theory this might reduce the side effects of vagotomy, it is unclear in practice that this had any effect on outcomes.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In a patient with acute severe upper GI bleeding, the differential diagnosis includes a bleeding peptic ulcer, bleeding esophageal or gastric varices secondary to portal hypertension, esophageal mucosal diseases such as severe esophagitis and Mallory-Weiss tears, gastric arteriovenous malformations and Dieulafoy’s lesion, and rarely, ulcerated tumors or hemobilia.

In a patient with acute abdominal pain and free air, the differential diagnosis should include a perforated peptic ulcer, perforated diverticulitis, perforated appendicitis, and small bowel perforation.

In the patient with gastric outlet obstruction, the differential diagnosis includes PUD, gastric cancer, duodenal web, functional delay in gastric emptying, and chronic ulcer disease related to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) or aspirin use.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The majority of operations for PUD performed now are urgent or emergent operations for complicated ulcer disease.

A thorough history and physical should be obtained with key focus on the duration of symptoms, previous ulcer therapy, NSAID or aspirin use, and smoking history. Consider investigation into hypersecretory and malignant etiologies in patients with refractory ulcer disease.

Patients should be specifically questioned regarding H. pylori status and prior H. pylori treatment including a history of eradication. In patients unable to stop antiinflammatory drug use or those with H. pylori-negative ulcer disease, it may be reasonable to consider performing an acid-reducing procedure at the time of ulcer repair.

Bleeding can occur in 15% to 20% of patients with PUD and is the most common ulcer-related complication.4 The majority will resolve with conservative or endoscopic treatment. In patients undergoing operation for a bleeding duodenal ulcer, the best available evidence suggests that vagotomy should be combined with oversewing of a duodenal ulcer.5 As such, the patient’s H. pylori status, history of prior NSAID use, or prior ulcer disease will not affect the use of vagotomy in the management of their bleeding duodenal ulcer

Perforations occur in up to 10% of ulcer complications.4 Patients that will most likely to benefit from acid-reducing surgical intervention during repair of a perforation include those that have contraindications to PPI, perforation on PPI, or prior eradication of H. pylori.

Obstruction is the least common complication of ulcer disease at 5% to 8% and occurs as a result of scarring of the pylorus.4 Endoscopy often delineates location and degree of the obstruction and also allows for therapeutic balloon dilation of the pylorus. Surgery is reserved for failure of less invasive treatments.

Intractable disease encompasses failure of medical management to heal the ulcer, relapse of disease while on current therapy, or multiple courses of medical therapy. Medical management includes acid suppression, H. pylori eradication, and NSAID cessation. Symptoms should be substantiated with endoscopic visualization of a persistent or recurring ulcer.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

In a patient with sudden onset acute abdominal pain and physical exam findings of peritonitis, an upright chest radiograph confirming the finding of free intraperitoneal air is a sufficient workup prior to proceeding to the operating room (OR) for a presumed perforated ulcer.

In patients with a history and physical consistent with a perforated ulcer, but without free air on radiograph, a computed tomography (CT) scan or upper GI contrast study using water-soluble contrast can help to make the diagnosis.

Testing for H. pylori is used to confirm presence of or gauge the eradication of disease. Antibody testing assesses overall exposure but is not specific for active disease. Urease breath test and stool antigen test can be used to confirm eradication. Full treatment of H. pylori should be attempted before definitive acid reduction surgery is considered.

Stool antigen testing for H. pylori should be performed prior to operation for PUD, as knowledge of H. pylori status may help determine the need for vagotomy. As mentioned earlier, it may not be necessary to perform vagotomy for H. pylori positive disease, but may be considered in treatment of H. pylori-negative ulcer disease.

Serum gastrin levels should be tested to rule out hypergastrinemic syndromes.

Endoscopy is part of standard investigation of ulcer disease when symptoms persist despite medical therapy. Endoscopy is also used to assess ulcer healing and perform biopsies to evaluate malignancy, gastritis, and H. pylori infection.

In patients with a bleeding peptic ulcer, the surgeon should be present at the time of upper endoscopy to gain an accurate anatomic understanding of the location of the ulcer. Patients with gastric ulcers not caused by acid, such as ulcers along the lesser curvature proximal to the incisura or near the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, will not require a vagotomy. Patients with duodenal or prepyloric ulcer should undergo vagotomy at the time of their operation for bleeding control.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Patients undergoing emergency surgery for peptic ulcer bleeding will have a stomach full of blood and are at significant risk of aspiration. A nasogastric tube should be placed prior to induction for all vagotomy procedures, and rapid sequence induction should be used if possible.

When performing an emergency operation for bleeding, the surgeon should ensure that blood is cross-matched and available.

For laparoscopic procedures, having the ability to perform intraoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) can facilitate the identification of the ulcer in difficult cases.

With truncal vagotomy, the gastric antrum and pylorus are denervated and concomitant drainage procedure must be performed.

Options include pyloroplasty, gastrojejunostomy, or gastric resection with reconstruction (see Part 2, Chapter 9).

HSV preserves antral muscular function and the pylorus mechanism. It is not necessary to perform a drainage procedure.

Transthoracic vagotomy requires double lumen intubation tube and separate lung ventilation; for sufficient exposure to distal esophagus, the left lung must be collapsed.

Perioperative antibiotics should be administered; cefazolin is standard, clindamycin plus a fluoroquinolone or aminoglycoside for penicillin allergy.

Positioning—Open

Open approach: Patient is supine with the arms tucked or extended.

Space is left on the patient’s left side to attach a Bookwalter or Omni retractor to the bed rail.

Reverse Trendelenburg position of the table will help with exposure of the hiatus.

Positioning—Laparoscopic

Laparoscopic approach: Patient is supine with right arm tucked. Surgeon stands on patient’s right and assistant stands on patient’s left.

Reverse Trendelenburg position of the table will help with exposure of the hiatus.

Positioning—Transthoracic

Patient is placed in right lateral decubitus position.

TECHNIQUES

TRUNCAL VAGOTOMY—OPEN

Skin Incision and Retractor Positioning

Use a standard upper midline incision, from just below xiphoid process to level of the umbilicus.

A body wall retractor blade is placed on either side of the upper half of the incision to facilitate exposure.

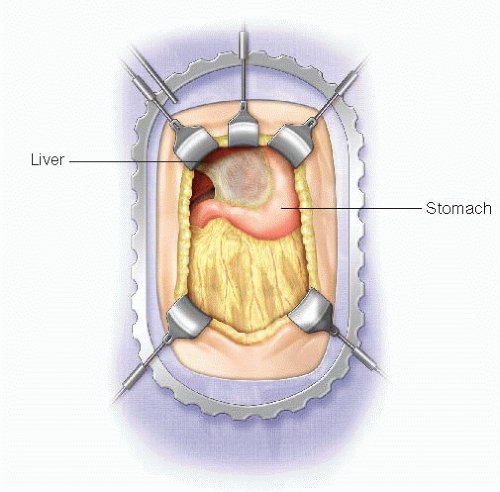

Depending on the size of the left lateral segment of the liver, it may be necessary to divide the avascular portion of the left triangular ligament to allow the left lateral segment to be retracted in order to facilitate visualization of the abdominal esophagus (FIG 1).

Exposure of the Esophagus

The pars flaccida and the phrenoesophageal ligament are divided to expose the right crus and anterior esophageal wall. Take caution to recognize and preserve an accessory left hepatic artery when dividing the pars flaccida. The position of the esophagus can be verified by palpation of the nasogastric tube within the lumen of the esophagus.

Identify the right crus of the diaphragm; gently dissect to expose the anterior surface of the esophagus. This peritoneal incision should be carried across the

anterior surface of the esophagus and onto the left crus of the diaphragm to expose the anterior surface of the esophagus (FIG 2A). By applying downward and rightward traction on the stomach, the surgeon can place the esophagus on tension to enhance exposure (FIG 2B).

Continue to develop a plane between right crus and the esophagus; extend posteriorly to create a retroesophageal window.

The esophagus is then dissected circumferentially and this, again, can be facilitated by palpating the nasogastric tube in the lumen of the esophagus.

A Penrose drain is placed around the GE junction to assist with downward traction on the GE junction.

Identification and Division of the Anterior (Left) Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerves rotate counterclockwise at the level of the esophageal hiatus with the right vagus nerve coursing more posterior and the left vagus nerve anterior with respect to the esophagus.

The left (anterior) vagus nerve is typically anterior and just right of midline at the 1 o’clock to 2 o’clock position. It is often almost within the longitudinal muscle layer (FIG 3).

Downward traction of the GE junction via the Penrose drain can help tense the nerve like a guitar string to help with palpation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree