- Chlamydial infection. Chlamydial infection causes a yellow, mucopurulent, odorless, or acrid vaginal discharge. Other findings include dysuria, dyspareunia, and vaginal bleeding after douching or coitus, especially following menses. Many women remain asymptomatic.

- Endometritis. A scant, serosanguineous discharge with a foul odor can result from bacterial invasion of the endometrium. Associated findings include fever, lower back and abdominal pain, abdominal muscle spasm, malaise, dysmenorrhea, and an enlarged uterus.

- Genital warts. Genital warts are mosaic, papular vulvar lesions that can cause a profuse, mucopurulent vaginal discharge, which may be foul smelling if the warts are infected. Patients frequently complain of burning or paresthesia in the vaginal introitus.

- Gonorrhea. Although 80% of women with gonorrhea are asymptomatic, others have a yellow or green, foul-smelling discharge that can be expressed from Bartholin’s or Skene’s ducts. Other findings include dysuria, urinary frequency and incontinence, bleeding, and vaginal redness and swelling. Severe pelvic and lower abdominal pain and fever may develop.

- Gynecologic cancer. Endometrial or cervical cancer produces a chronic, watery, bloody, or purulent vaginal discharge that may be foul smelling. Other findings include abnormal vaginal bleeding and, later, weight loss; pelvic, back, and leg pain; fatigue; urinary frequency; and abdominal distention.

- Herpes simplex (genital). A copious mucoid discharge can result from herpes simplex, but the initial complaint is painful, indurated vesicles and ulcerations on the labia, vagina, cervix, anus, thighs, or mouth. Erythema, marked edema, and tender inguinal lymph nodes may occur with fever, malaise, and dysuria.

- Trichomoniasis. Trichomoniasis can cause a foul-smelling discharge, which may be frothy, green-yellow, and profuse or thin, white, and scant. Other findings include pruritus; a red, inflamed vagina with tiny petechiae; dysuria and urinary frequency; and dyspareunia, postcoital spotting, menorrhagia, or dysmenorrhea. About 70% of patients are asymptomatic.

Other Causes

- Contraceptive creams and jellies. Contraceptive creams and jellies can increase vaginal secretions.

- Drugs. Drugs that contain estrogen, including hormonal contraceptives, can cause increased mucoid vaginal discharge. Antibiotics, such as tetracycline, may increase the risk of a candidal vaginal infection and discharge.

- Radiation therapy. Irradiation of the reproductive tract can cause a watery, odorless vaginal discharge.

Special Considerations

Teach the patient to keep her perineum clean and dry. Also, tell her to avoid wearing tight-fitting clothing and nylon underwear and to instead wear cotton-crotched underwear and pantyhose. If appropriate, suggest that the patient douche with a solution of 5 T of white vinegar to 2 qt (2 L) of warm water to help relieve her discomfort.

If the patient has a vaginal infection, tell her to continue taking the prescribed medication even if her symptoms clear or she menstruates. Also, advise her to avoid intercourse until her symptoms clear and then to have her partner use condoms until she completes her course of medication. If her condition is sexually transmitted, instruct her on safe sex methods.

Patient Counseling

Emphasize the importance of keeping the perineum clean and dry and avoiding tight-fitting clothing. Suggest douching with vinegar and water to relieve discomfort, if appropriate, and stress compliance with the prescribed drug regimen. Instruct the patient to avoid intercourse until symptoms of infection clear, and provide information on safer sex practices.

Pediatric Pointers

Female neonates who have been exposed to maternal estrogens in utero may have a white mucous vaginal discharge for the first month after birth; a yellow mucous discharge indicates a pathologic condition. In the older child, a purulent, foul-smelling, and possibly bloody vaginal discharge commonly results from a foreign object placed in the vagina. The possibility of sexual abuse should also be considered.

Geriatric Pointers

The postmenopausal vaginal mucosa becomes thin due to decreased estrogen levels. Together with a rise in vaginal pH, this reduces resistance to infectious agents, increasing the incidence of vaginitis.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

Schuiling, K. D. (2013). Women’s gynecologic health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Vertigo

Vertigo is an illusion of movement in which the patient feels that he’s revolving in space (subjective vertigo) or that his surroundings are revolving around him (objective vertigo). He may complain of feeling pulled sideways, as though drawn by a magnet.

A common symptom, vertigo usually begins abruptly and may be temporary or permanent and mild or severe. It may worsen when the patient moves and subside when he lies down. It’s often confused with dizziness — a sensation of imbalance and light-headedness that is nonspecific. However, unlike dizziness, vertigo is commonly accompanied by nausea, vomiting, nystagmus, and tinnitus or hearing loss. Although the patient’s limb coordination is unaffected, vertiginous gait may occur.

Vertigo may result from a neurologic or otologic disorder that affects the equilibratory apparatus (the vestibule, semicircular canals, eighth cranial nerve, vestibular nuclei in the brain stem and their temporal lobe connections, and eyes). However, this symptom may also result from alcohol intoxication, hyperventilation, and postural changes (benign postural vertigo). It may also be an adverse effect of certain drugs, tests, or procedures.

History and Physical Examination

Ask your patient to describe the onset and duration of his vertigo, being careful to distinguish this symptom from dizziness. Does he feel that he’s moving or that his surroundings are moving around him? How often do the attacks occur? Do they follow position changes, or are they unpredictable? Find out if the patient can walk during an attack, if he leans to one side, and if he’s ever fallen. Ask if he experiences motion sickness and if he prefers one position during an attack. Obtain a recent drug history, and note any evidence of alcohol abuse.

Perform a neurologic assessment, focusing particularly on eighth cranial nerve function. Observe the patient’s gait and posture for abnormalities.

Medical Causes

- Acoustic neuroma. Acoustic neuroma is a tumor of the eighth cranial nerve that causes mild, intermittent vertigo and unilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Other findings include tinnitus, postauricular or suboccipital pain, and — with cranial nerve compression — facial paralysis.

- Benign positional vertigo. With benign positional vertigo, debris in a semicircular canal produces vertigo on head position change, which lasts a few minutes. It’s usually temporary and can be effectively treated with positional maneuvers.

- Brain stem ischemia. Brain stem ischemia produces sudden, severe vertigo that may become episodic and later persistent. Associated findings include ataxia, nausea, vomiting, increased blood pressure, tachycardia, nystagmus, and lateral deviation of the eyes toward the side of the lesion. Hemiparesis and paresthesia may also occur.

- Head trauma. Persistent vertigo, occurring soon after injury, accompanies spontaneous or positional nystagmus and, if the temporal bone is fractured, hearing loss. Associated findings include headache, nausea, vomiting, and decreased LOC. Behavioral changes, diplopia or visual blurring, seizures, motor or sensory deficits, and signs of increased intracranial pressure may also occur.

- Herpes zoster. Infection of the eighth cranial nerve produces sudden onset of vertigo accompanied by facial paralysis, hearing loss in the affected ear, and herpetic vesicular lesions in the auditory canal.

- Labyrinthitis. Severe vertigo begins abruptly with labyrinthitis, an inner ear infection. Vertigo may occur in a single episode or may recur over months or years. Associated findings include nausea, vomiting, progressive sensorineural hearing loss, and nystagmus.

- Ménière’s disease. With Ménière’s disease, labyrinthine dysfunction causes abrupt onset of vertigo, lasting minutes, hours, or days. Unpredictable episodes of severe vertigo, hearing loss, and unsteady gait may cause the patient to fall. During an attack, any sudden motion of the head or eyes can precipitate nausea and vomiting.

- Multiple sclerosis (MS). Episodic vertigo may occur early and become persistent. Other early findings include diplopia, visual blurring, and paresthesia. MS may also produce nystagmus, constipation, muscle weakness, paralysis, spasticity, hyperreflexia, intention tremor, and ataxia.

- Seizures. Temporal lobe seizures may produce vertigo, usually associated with other symptoms of partial complex seizures.

- Vestibular neuritis. With vestibular neuritis, severe vertigo usually begins abruptly and lasts several days, without tinnitus or hearing loss. Other findings include nausea, vomiting, and nystagmus.

Other Causes

- Diagnostic tests. Caloric testing (irrigating the ears with warm or cold water) can induce vertigo.

- Drugs and alcohol. High or toxic doses of certain drugs or alcohol may produce vertigo. These drugs include salicylates, aminoglycosides, antibiotics, quinine, and hormonal contraceptives.

- Surgery and other procedures. Ear surgery may cause vertigo that lasts for several days. Also, administration of overly warm or cold eardrops or irrigating solutions can cause vertigo.

Special Considerations

Place the patient in a comfortable position, and monitor his vital signs and LOC. Keep the side rails up if he’s in bed, or help him to a chair if he’s standing when vertigo occurs. Darken the room and keep him calm. Administer drugs to control nausea and vomiting and meclizine or dimenhydrinate to decrease labyrinthine irritability.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as electronystagmography, EEG, and X-rays of the middle and inner ears.

Patient Counseling

Explain the need for moving around with assistance. Emphasize the need to avoid sudden position changes and performing dangerous tasks.

Pediatric Pointers

Ear infection is a common cause of vertigo in children. Vestibular neuritis may also cause this symptom.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Vesicular Rash

A vesicular rash is a scattered or linear distribution of blister-like lesions — sharply circumscribed and filled with clear, cloudy, or bloody fluid. The lesions, which are usually less than 0.5 cm in diameter, may occur singly or may occur in groups. (See Recognizing Common Skin Lesions, page 551.) They sometimes occur with bullae — fluid-filled lesions that are larger than 0.5 cm in diameter.

A vesicular rash may be mild or severe and temporary or permanent. It can result from infection, inflammation, or allergic reactions.

History and Physical Examination

Ask your patient when the rash began, how it spread, and whether it has appeared before. Did other skin lesions precede eruption of the vesicles? Obtain a thorough drug history. If the patient has used a topical medication, what type did he use and when was it last applied? Also, ask about associated signs and symptoms. Find out if he has a family history of skin disorders, and ask about allergies, recent infections, insect bites, and exposure to allergens.

Examine the patient’s skin, noting if it’s dry, oily, or moist. Observe the general distribution of the lesions, and record their exact location. Note the color, shape, and size of the lesions, and check for crusts, scales, scars, macules, papules, or wheals. Palpate the vesicles or bullae to determine if they’re flaccid or tense. Slide your finger across the skin to see if the outer layer of epidermis separates easily from the basal layer (Nikolsky’s sign).

Medical Causes

- Burns (second degree). Thermal burns that affect the epidermis and part of the dermis cause vesicles and bullae, with erythema, swelling, pain, and moistness.

- Dermatitis. With contact dermatitis, a hypersensitivity reaction produces an eruption of small vesicles surrounded by redness and marked edema. The vesicles may ooze, scale, and cause severe pruritus.

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a skin disease that’s most common in men between ages 20 and 50 (and is occasionally associated with celiac disease, organ malignancy, or immunoglobulin A immunotherapy) and produces a chronic inflammatory eruption marked by vesicular, papular, bullous, pustular, or erythematous lesions. Usually, the rash is symmetrically distributed on the buttocks, shoulders, extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, and sometimes the face, scalp, and neck. Other symptoms include severe pruritus, burning, and stinging.

With nummular dermatitis, groups of pinpoint vesicles and papules appear on erythematous or pustular lesions that are nummular (coinlike) or annular (ringlike). Often, the pustular lesions ooze a purulent exudate, itch severely, and rapidly become crusted and scaly. Two or three lesions may develop on the hands, but the lesions typically develop on the extensor surfaces of the limbs and on the buttocks and posterior trunk.

- Erythema multiforme. Erythema multiforme is an acute inflammatory skin disease that’s heralded by a sudden eruption of erythematous macules, papules and, occasionally, vesicles and bullae. The characteristic rash appears symmetrically over the hands, arms, feet, legs, face, and neck and tends to reappear. Although vesicles and bullae may also erupt on the eyes and genitalia, vesiculobullous lesions usually appear on the mucous membranes — especially the lips and buccal mucosa — where they rupture and ulcerate, producing a thick, yellow or white exudate. Bloody, painful crusts, a foul-smelling oral discharge, and difficulty chewing may develop. Lymphadenopathy may also occur.

- Herpes simplex. Herpes simplex is a common viral infection that produces groups of vesicles on an inflamed base, most commonly on the lips and lower face. In about 25% of cases, the genital region is the site of involvement. Vesicles are preceded by itching, tingling, burning, or pain; develop singly or in groups;, are 2 to 3 mm in size; and do not coalesce. Eventually, they rupture, forming a painful ulcer followed by a yellowish crust.

- Herpes zoster. With herpes zoster, a vesicular rash is preceded by erythema and, occasionally, by a nodular skin eruption and unilateral, sharp, pain along a dermatome. About 5 days later, the lesions erupt and the pain becomes burning. Vesicles dry and scab about 10 days after eruption. Associated findings include fever, malaise, pruritus, and paresthesia or hyperesthesia of the involved area. Herpes zoster involving the cranial nerves produces facial palsy, hearing loss, dizziness, loss of taste, eye pain, and impaired vision.

- Insect bites. With insect bites, vesicles appear on red hivelike papules and may become hemorrhagic.

- Pemphigoid (bullous). Generalized pruritus or an urticarial or eczematous eruption may precede pemphigoid — a classic bullous rash. Bullae are large, thick walled, tense, and irregular, typically forming on an erythematous base. They usually appear on the arms, legs, trunk, mouth, or other mucous membranes.

- Pompholyx (dyshidrosis or dyshidrosis eczema). Pompholyx is a common, recurrent disorder that produces symmetrical vesicular lesions that can become pustular. The pruritic lesions are more common on the palms than on the soles and may be accompanied by minimal erythema.

- Porphyria cutanea tarda. Bullae — especially on areas exposed to sun, friction, trauma, or heat — result from abnormal porphyrin metabolism. Photosensitivity is also a common sign. Papulovesicular lesions evolving into erosions or ulcers and scars may appear. Chronic skin changes include hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, hypertrichosis, and sclerodermoid lesions. Urine is pink to brown.

- Scabies. Small vesicles erupt on an erythematous base and may be at the end of a threadlike burrow. Burrows are a few millimeters long, with a swollen nodule or red papule that contains the mite. Pustules and excoriations may also occur. Men may develop burrows on the glans, shaft, and scrotum; women may develop burrows on the nipples. Both sexes may develop burrows on the webs of the fingers, wrists, elbows, axillae, and waistline. Associated pruritus worsens with inactivity and warmth and at night.

- Smallpox (variola major). Initial signs and symptoms of smallpox include high fever, malaise, prostration, severe headache, backache, and abdominal pain. A maculopapular rash develops on the mucosa of the mouth, pharynx, face, and forearms and then spreads to the trunk and legs. Within 2 days, the rash becomes vesicular and later pustular. The lesions develop at the same time, appear identical, and are more prominent on the face and extremities. The pustules are round, firm, and deeply embedded in the skin. After 8 to 9 days, the pustules form a crust. Later, the scab separates from the skin, leaving a pitted scar. In fatal cases, death results from encephalitis, extensive bleeding, or secondary infection.

- Tinea pedis. Tinea pedis is a fungal infection that causes vesicles and scaling between the toes and, possibly, scaling over the entire sole. Severe infection causes inflammation, pruritus, and difficulty walking.

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis. Toxic epidermal necrolysis is an immune reaction to drugs or other toxins, in which vesicles and bullae are preceded by a diffuse, erythematous rash and followed by large-scale epidermal necrolysis and desquamation. Large, flaccid bullae develop after mucous membrane inflammation, a burning sensation in the conjunctivae, malaise, fever, and generalized skin tenderness. The bullae rupture easily, exposing extensive areas of denuded skin. (See Drugs That Cause Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis.)

Special Considerations

Any skin eruption that covers a large area may cause substantial fluid loss through the vesicles, bullae, or other weeping lesions. If necessary, start an I.V. line to replace fluids and electrolytes. Keep the patient’s environment warm and free from drafts, cover him with sheets or blankets as necessary, and take his rectal temperature every 4 hours because increased fluid loss and increased blood flow to inflamed skin may lead to hyperthermia.

Drugs That Cause Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Various drugs can trigger toxic epidermal necrolysis — a rare but potentially fatal immune reaction characterized by a vesicular rash. This type of necrolysis produces large, flaccid bullae that rupture easily, exposing extensive areas of denuded skin. The resulting loss of fluid and electrolytes — along with widespread systemic involvement — can lead to such life-threatening complications as pulmonary edema, shock, renal failure, sepsis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Here’s a list of some drugs that can cause toxic epidermal necrolysis:

- Allopurinol

- Aspirin

- Barbiturates

- Chloramphenicol

- Chlorpropamide

- Gold salts

- Nitrofurantoin

- Penicillin

- Phenytoin

- Primidone

- Sulfonamides

- Tetracycline

Obtain cultures to determine the standard causative organism. Use precautions until infection is ruled out. Tell the patient to wash his hands often and not to touch the lesions. Be alert for signs of secondary infection. Give the patient an antibiotic, and apply corticosteroid or antimicrobial ointment to the lesions.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of frequent hand washing and the need to avoid touching the lesions. Instruct the patient to use tepid baths or cold compresses to relieve itching.

Pediatric Pointers

Vesicular rashes in children are caused by staphylococcal infections (staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a life-threatening infection occurring in infants), varicella, hand-foot-and-mouth disease, contact dermatitis, and miliaria rubra.

Reference

Wolff, K., & Johnson, R. A. (2009). Fitzpatrick’s color atlas & synopsis of clinical dermatology (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical.

Violent Behavior

Marked by sudden loss of self-control, violent behavior refers to the use of physical force to violate, injure, or abuse an object or person. This behavior may also be self-directed. It may result from an organic or psychiatric disorder or from the use of certain drugs.

History and Physical Examination

During your evaluation, determine if the patient has a history of violent behavior. Is he intoxicated or suffering symptoms of alcohol or drug withdrawal? Does he have a history of family violence, including corporal punishment and child or spouse abuse? (See Understanding Family Violence.)

Watch for clues indicating that the patient is losing control and may become violent. Has he exhibited abrupt behavioral changes? Is he unable to sit still? Increased activity may indicate an attempt to discharge aggression. Does he suddenly cease activity (suggesting the calm before the storm)? Does he make verbal threats or angry gestures? Is he jumpy, extremely tense, or laughing? Such intensifying of emotion may herald loss of control.

If your patient’s violent behavior is a new development, he may have an organic disorder. Obtain a medical history, and perform a physical examination. Watch for a sudden change in his level of consciousness. Disorientation, failure to recall recent events, and display of tics, jerks, tremors, and asterixis all suggest an organic disorder.

Medical Causes

- Organic disorders. Disorders resulting from metabolic or neurologic dysfunction can cause violent behavior. Common causes include epilepsy, brain tumor, encephalitis, head injury, endocrine disorders, metabolic disorders (such as uremia and calcium imbalance), and severe physical trauma.

- Psychiatric disorders. Violent behavior occurs as a protective mechanism in response to a perceived threat in psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. A similar response may occur in personality disorders, such as antisocial or borderline personality.

Understanding Family Violence

Effectively managing the violent patient requires an understanding of the roots of his behavior. For example, his behavior may be spawned by a family history of corporal punishment or child or spouse abuse. His violent behavior may also be associated with drug or alcohol abuse and fixed family roles that stifle growth and individuality.

CAUSES OF FAMILY VIOLENCE

Social scientists suggest that family violence stems from cultural attitudes fostering violence and from the frustration and stress associated with overcrowded living conditions and poverty. Albert Bandura, a social learning theorist, believes that individuals learn violent behavior by observing and imitating other family members who vent their aggressive feelings through verbal abuse and physical force. (They also learn from television and the movies, especially when the violent hero gains power and recognition.) Members of families with these characteristics may have an increased potential for violent behavior, thus initiating a cycle of violence that passes from generation to generation.

Other Causes

- Drugs and alcohol. Violent behavior is an adverse effect of some drugs, such as lidocaine and penicillin G. Alcohol abuse or withdrawal, hallucinogens, amphetamines, and barbiturate withdrawal may also cause violent behavior.

Special Considerations

Violent behavior is most prevalent in emergency departments, critical care units, and crisis and acute psychiatric units. Natural disasters and accidents also increase the potential for violent behavior, so be on guard in these situations.

If your patient becomes violent or potentially violent, your goal is to remain composed and to establish environmental control. First, protect yourself. Remain at a distance from the patient, call for assistance, and don’t overreact. Remain calm, and make sure you have enough personnel for a show of force to subdue or restrain the patient if necessary. Encourage the patient to move to a quiet location — free from noise, activity, and people — to avoid frightening or stimulating him further. Reassure him, explain what’s happening, and tell him that he’s safe.

If the patient makes violent threats, take them seriously, and inform those at whom the threats are directed. If ordered, administer a psychotropic medication.

Remember that your own attitudes can affect your ability to care for a violent patient. If you feel fearful or judgmental, ask another staff member for help.

Patient Counseling

Reassure the patient, explain what’s happening, and tell him that he is safe. After the patient is calm, explain the reason for his violent behavior, if known.

Pediatric Pointers

Adolescents and younger children often make threats resulting from violent dreams or fantasies or unmet needs. Adolescents who exhibit extreme violence can come from families with a history of physical or psychological abuse. These children may display violent behavior toward their peers, siblings, and pets.

Vision Loss

Vision loss — the inability to perceive visual stimuli — can be sudden or gradual and temporary or permanent. The deficit can range from a slight impairment of vision to total blindness. It can result from an ocular, a neurologic, or a systemic disorder or from trauma or the use of certain drugs. The ultimate visual outcome may depend on early, accurate diagnosis and treatment.

History and Physical Examination

Sudden vision loss can signal an ocular emergency. (See Managing Sudden Vision Loss.) Don’t touch the eye if the patient has perforating or penetrating ocular trauma.

If the patient’s vision loss occurred gradually, ask him if the vision loss affects one eye or both and all or only part of the visual field. Is the visual loss transient or persistent? Did the visual loss occur abruptly, or did it develop over hours, days, or weeks? What is the patient’s age? Ask the patient if he has experienced photosensitivity, and ask him about the location, intensity, and duration of any eye pain. You should also obtain an ocular history and a family history of eye problems or systemic diseases that may lead to eye problems, such as hypertension; diabetes mellitus; thyroid, rheumatic, or vascular disease; infections; and cancer.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS Managing Sudden Vision Loss

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS Managing Sudden Vision Loss

Sudden vision loss can signal central retinal artery occlusion or acute angle-closure glaucoma — ocular emergencies that require immediate intervention. If your patient reports sudden vision loss, immediately notify an ophthalmologist for an emergency examination, and perform these interventions:

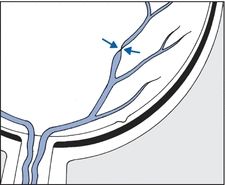

For a patient with suspected central retinal artery occlusion, perform light massage over his closed eyelid. Increase his carbon dioxide level by administering a set flow of oxygen and carbon dioxide through a Venturi mask, or have the patient rebreathe in a paper bag to retain exhaled carbon dioxide. These steps will dilate the artery and, possibly, restore blood flow to the retina.

For a patient with suspected acute angle-closure glaucoma, measure intraocular pressure (IOP) with a tonometer. (You can also estimate IOP without a tonometer by placing your fingers over the patient’s closed eyelid. A rock-hard eyeball usually indicates increased IOP.) Expect to instill pressure-reducing drops, and administer I.V. acetazolamide to help decrease IOP.

Suspected Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree