EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Your first priority is to ensure a patent airway. Insert an artificial airway, and institute measures to prevent aspiration. (Don’t disrupt spinal alignment if you suspect spinal cord injury.) Suction the patient as necessary.

Next, examine spontaneous respirations. Give supplemental oxygen, and ventilate the patient with a handheld resuscitation bag, if necessary. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be indicated. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment handy. Make sure to check the patient’s chart for a do-not-resuscitate order.

History and Physical Examination

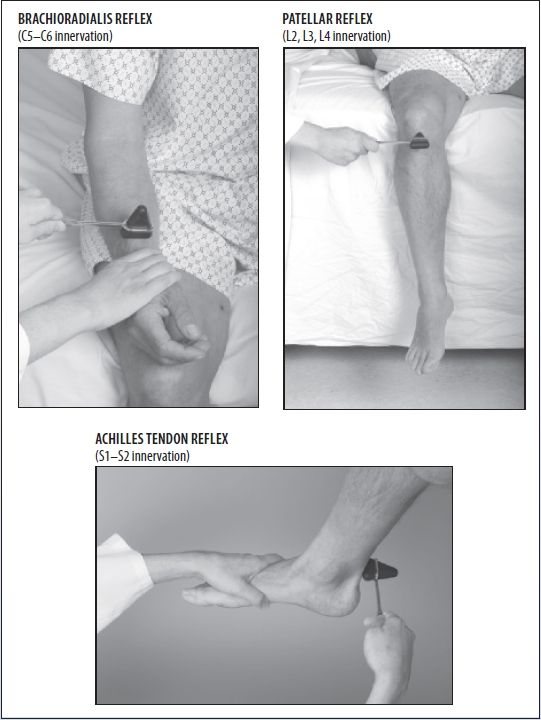

After taking the patient’s vital signs, determine his level of consciousness (LOC). Use the Glasgow Coma Scale as a reference. Then, evaluate the pupils for size, equality, and response to light. Test deep tendon reflexes and cranial nerve reflexes, and check for doll’s eye sign.

Next, explore the history of the patient’s coma. If you can’t obtain this information, look for clues to the causative disorder, such as hepatomegaly, cyanosis, diabetic skin changes, needle tracks, or obvious trauma. If a family member is available, find out when the patient’s LOC began deteriorating. Did it occur abruptly? What did the patient complain of before he lost consciousness? Does he have a history of diabetes, liver disease, cancer, blood clots, or aneurysm? Ask about any accident or trauma responsible for the coma.

Medical Causes

- Brain stem infarction. When brain stem infarction produces a coma, decerebrate posture may be elicited. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the severity of the infarct and may include cranial nerve palsies, bilateral cerebellar ataxia, and sensory loss. With deep coma, all normal reflexes are usually lost, resulting in the absence of doll’s eye sign, a positive Babinski’s reflex, and flaccidity.

- Cerebral lesion. Whether the cause is trauma, a tumor, an abscess, or an infarction, any cerebral lesion that increases ICP may also produce decerebrate posture. Typically, this posture is a late sign. Associated findings vary with the lesion’s site and extent, but commonly include coma, abnormal pupil size and response to light, and the classic triad of increased ICP — bradycardia, increasing systolic blood pressure, and a widening pulse pressure.

Comparing Decerebrate and Decorticate Postures

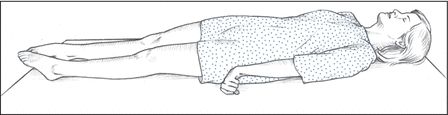

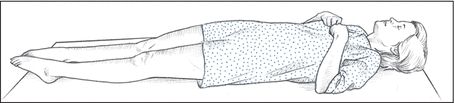

Decerebrate posture results from damage to the upper brain stem. In this posture, the arms are adducted and extended, with the wrists pronated and the fingers flexed. The legs are stiffly extended, with plantar flexion of the feet.

Decorticate posture results from damage to one or both corticospinal tracts. In this posture, the arms are adducted and flexed, with the wrists and fingers flexed on the chest. The legs are stiffly extended and internally rotated, with plantar flexion of the feet.

- Hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy, deterioration of the brain, occurs when the liver is not able to function normally to remove toxic substances, thus allowing them to enter the brain and nervous system. Decerebrate posturing and coma occur in the later stage of hepatic encephalopathy, the comatose stage, as the patient’s condition deteriorates. Additional signs include hyperactive reflexes, a positive Babinski’s reflex, and fetor hepaticus. Other symptoms — disorientation, slurred speech, forgetfulness, tremors, asterixis, lethargy, stupor, and hyperventilation — occur during earlier stages.

- Hypoglycemic encephalopathy. Characterized by extremely low blood glucose levels, hypoglycemic encephalopathy may produce decerebrate posture and coma. It also causes dilated pupils, slow respirations, and bradycardia. Muscle spasms, twitching, and seizures eventually progress to flaccidity.

- Hypoxic encephalopathy. Severe hypoxia may produce decerebrate posture — the result of brain stem compression associated with anaerobic metabolism and increased ICP. Other findings include coma, a positive Babinski’s reflex, an absence of doll’s eye sign, hypoactive deep tendon reflexes and, possibly, fixed pupils and respiratory arrest.

- Pontine hemorrhage. Typically, pontine hemorrhage, a life-threatening disorder, rapidly leads to decerebrate posture with coma. Accompanying signs include total paralysis, the absence of doll’s eye sign, a positive Babinski’s reflex, and small, reactive pupils.

- Posterior fossa hemorrhage. Posterior fossa hemorrhage is a subtentorial lesion that causes decerebrate posture. Its early signs and symptoms include vomiting, a headache, vertigo, ataxia, a stiff neck, drowsiness, papilledema, and cranial nerve palsies. The patient eventually slips into coma and may experience respiratory arrest.

Other Causes

- Diagnostic tests. Relief from high ICP by removing spinal fluid during a lumbar puncture may precipitate cerebral compression of the brain stem and cause decerebrate posture and coma.

Special Considerations

Help prepare the patient and his family for diagnostic tests that will determine the cause of his decerebrate posture. Diagnostic tests include skull X-rays, a computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, cerebral angiography, digital subtraction angiography, EEG, a brain scan, and ICP monitoring.

Monitor the patient’s neurologic status and vital signs every 30 minutes or as indicated. Also, be alert for signs of increased ICP (bradycardia, increasing systolic blood pressure, and a widening pulse pressure) and neurologic deterioration (an altered respiratory pattern and abnormal temperature).

Inform the patient’s family that decerebrate posture is a reflex response — not a voluntary response to pain or a sign of recovery. Offer emotional support.

Patient Counseling

Explain that decerebrate posture is a reflex response. Provide emotional support to the patient and his family.

Pediatric Pointers

Children younger than age 2 may not display decerebrate posture because the nervous system is still immature. However, if the posture occurs, it’s usually the more severe opisthotonos. In fact, opisthotonos is more common in infants and young children than in adults and is usually a terminal sign. In children, the most common cause of decerebrate posture is head injury. It also occurs with Reye’s syndrome — the result of increased ICP causing brain stem compression.

REFERENCES

Goswami, R. P., Mukherjee, A., Biswas, T., Karmakar, P. S., & Ghosh, A. (2012). Two cases of dengue meningitis: A rare first presentation. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 6(2), 208–211.

Yildizdas, D., Kendirli, T., Arslanköylü, A. E. Horoz, O. O., Incecik, F., … Ince, E., (2011). Neurological complications of pandemic influenza (H1N1) in children. European Journal of Pediatrics, 170(6), 779–788.

Decorticate Posture

(See Also Decerebrate Posture) [Decorticate rigidity, abnormal flexor response]

A sign of corticospinal tract damage, decorticate posture is characterized by adduction of the arms and flexion of the elbows, with wrists and fingers flexed on the chest. The legs are extended and internally rotated, with plantar flexion of the feet. This posture may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. It usually results from stroke or head injury. It may be elicited by noxious stimuli or may occur spontaneously. The intensity of the required stimulus, the duration of the posture, and the frequency of spontaneous episodes vary with the severity and location of cerebral injury.

Although a serious sign, decorticate posture carries a more favorable prognosis than decerebrate posture. However, if the causative disorder extends lower in the brain stem, decorticate posture may progress to decerebrate posture. (See Comparing Decerebrate and Decorticate Postures, page 216.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Obtain the patient’s vital signs, and evaluate his level of consciousness (LOC). If his consciousness is impaired, insert an oropharyngeal airway, and take measures to prevent aspiration (unless spinal cord injury is suspected). Evaluate the patient’s respiratory rate, rhythm, and depth. Prepare to assist respirations with a handheld resuscitation bag or with intubation and mechanical ventilation, if necessary. Institute seizure precautions.

History and Physical Examination

Test the patient’s motor and sensory functions. Evaluate pupil size, equality, and response to light. Then, test cranial nerve function and deep tendon reflexes. Ask about headache, dizziness, nausea, changes in vision, and numbness or tingling. When did the patient first notice these symptoms? Is his family aware of behavioral changes? Also, ask about a history of cerebrovascular disease, cancer, meningitis, encephalitis, upper respiratory tract infection, bleeding or clotting disorders, or recent trauma.

Medical Causes

- Brain abscess. Decorticate posture may occur with brain abscess. Accompanying findings vary depending on the size and location of the abscess, but may include aphasia, hemiparesis, a headache, dizziness, seizures, nausea, and vomiting. The patient may also experience behavioral changes, altered vital signs, and a decreased LOC.

- Brain tumor. A brain tumor may produce decorticate posture that’s usually bilateral — the result of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) associated with tumor growth. Related signs and symptoms include a headache, behavioral changes, memory loss, diplopia, blurred vision or vision loss, seizures, ataxia, dizziness, apraxia, aphasia, paresis, sensory loss, paresthesia, vomiting, papilledema, and signs of hormonal imbalance.

- Head injury. Decorticate posture may be among the variable features of a head injury, depending on the site and severity of the injury. Associated signs and symptoms include a headache, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, irritability, a decreased LOC, aphasia, hemiparesis, unilateral numbness, seizures, and pupillary dilation.

- Intracerebral hemorrhage. Decorticate posturing can occur within hours in a patient who is diagnosed with an intracerebral hemorrhage, a life-threatening disorder that also produces a rapid, steady loss of consciousness. Associated symptoms can include a severe headache, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. Clinical findings may include increased blood pressure, irregular respirations, Babinski’s reflex, seizures, aphasia, hemiplegia, decerebrate posture, and dilated pupils.

- Stroke. Typically, a stroke involving the cerebral cortex produces unilateral decorticate posture, also called spastic hemiplegia. Other signs and symptoms include hemiplegia (contralateral to the lesion), dysarthria, dysphagia, unilateral sensory loss, apraxia, agnosia, aphasia, memory loss, a decreased LOC, urine retention, urinary incontinence, and constipation. Ocular effects include homonymous hemianopsia, diplopia, and blurred vision.

Special Considerations

Assess the patient frequently to detect subtle signs of neurologic deterioration. Also, monitor his neurologic status and vital signs every 30 minutes to 2 hours. Be alert for signs of increased ICP, including bradycardia, an increasing systolic blood pressure, and a widening pulse pressure.

Patient Counseling

Explain the signs and symptoms of decreased LOC and seizures. Explain to the caregiver how to keep the patient safe, especially during a seizure. Discuss any quality-of-life concerns, and provide needed referrals.

Pediatric Pointers

Decorticate posture is an unreliable sign before age 2 because of nervous system immaturity. In children, this posture usually results from head injury. It also occurs with Reye’s syndrome.

REFERENCES

Miller, L., Arakaki, L., & Ramautar, A. (2014). Elevated risk for invasive meningococcal disease among persons with HIV. Annals of Internal Medicine, 160(1): 30–37.

Waknine, Y. Meningococcal disease risk 10-fold higher in people with HIV. Medscape Medical News [serial online]. October 30, 2013; Accessed November 13, 2013. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/813519.

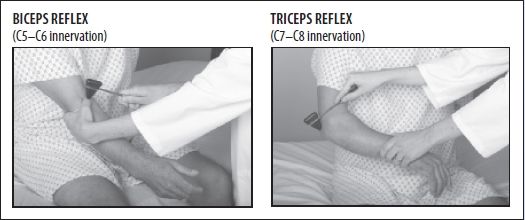

Deep Tendon Reflexes, Hyperactive

A hyperactive deep tendon reflex (DTR) is an abnormally brisk muscle contraction that occurs in response to a sudden stretch induced by sharply tapping the muscle’s tendon of insertion. This elicited sign may be graded as brisk or pathologically hyperactive. Hyperactive DTRs are commonly accompanied by clonus.

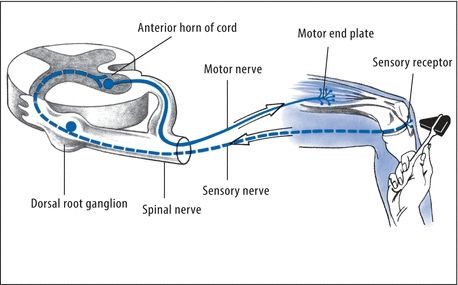

Understanding the Reflex Arc

The corticospinal tract and other descending tracts govern the reflex arc — the relay cycle that produces any reflex response. A corticospinal lesion above the level of the reflex arc being tested may result in hyperactive DTRs. Abnormal neuromuscular transmission at the end of the reflex arc may also cause hyperactive DTRs. For example, a calcium or magnesium deficiency may cause hyperactive DTRs because these electrolytes regulate neuromuscular excitability. (See Understanding the Reflex Arc.)

Although hyperactive DTRs typically accompany other neurologic findings, they usually lack specific diagnostic value. For example, they’re an early, cardinal sign of hypocalcemia.

History and Physical Examination

After eliciting hyperactive DTRs, take the patient’s history. Ask about spinal cord injury or other trauma and about prolonged exposure to cold, wind, or water. Could the patient be pregnant? A positive response to any of these questions requires prompt evaluation to rule out life-threatening autonomic hyperreflexia, tetanus, preeclampsia, or hypothermia. Ask about the onset and progression of associated signs and symptoms. Next, perform a neurologic examination. Evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness, and test motor and sensory function in the limbs. Ask about paresthesia. Check for ataxia or tremors and for speech and visual deficits. Test for Chvostek’s (an abnormal spasm of the facial muscles elicited by light taps on the facial nerve in a patient who has hypocalcemia) and Trousseau’s (a carpal spasm induced by inflating a sphygmomanometer cuff on the upper arm to a pressure exceeding systolic blood pressure for 3 minutes in a patient who has hypocalcemia or hypomagnesemia) signs and for carpopedal spasm. Ask about vomiting or altered bladder habits. Make sure to take the patient’s vital signs.

Medical Causes

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS produces generalized hyperactive DTRs accompanied by weakness of the hands and forearms and spasticity of the legs. Eventually, the patient develops atrophy of the neck and tongue muscles, fasciculations, weakness of the legs and, possibly, bulbar signs (dysphagia, dysphonia, facial weakness, and dyspnea).

- Brain tumor. A cerebral tumor causes hyperactive DTRs on the side opposite the lesion. Associated signs and symptoms develop slowly and may include unilateral paresis or paralysis, anesthesia, visual field deficits, spasticity, and a positive Babinski’s reflex.

- Hypocalcemia. Hypocalcemia may produce a sudden or gradual onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs with paresthesia, muscle twitching and cramping, positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs, carpopedal spasm, and tetany.

- Hypomagnesemia. Hypomagnesemia results in the gradual onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs accompanied by muscle cramps, hypotension, tachycardia, paresthesia, ataxia, tetany and, possibly, seizures.

- Hypothermia. Mild hypothermia (90°F to 94°F [32.2°C to 34.4°C]) produces generalized hyperactive DTRs. Other signs and symptoms include shivering, fatigue, weakness, lethargy, slurred speech, ataxia, muscle stiffness, tachycardia, diuresis, bradypnea, hypotension, and cold, pale skin.

- Preeclampsia. Occurring in pregnancy of at least 20 weeks’ gestation, preeclampsia may cause a gradual onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs. Accompanying signs and symptoms include increased blood pressure; abnormal weight gain; edema of the face, fingers, and abdomen after bed rest; albuminuria; oliguria; a severe headache; blurred or double vision; epigastric pain; nausea and vomiting; irritability; cyanosis; shortness of breath; and crackles. If preeclampsia progresses to eclampsia, the patient develops seizures.

- Spinal cord lesion. Incomplete spinal cord lesions cause hyperactive DTRs below the level of the lesion. In a traumatic lesion, hyperactive DTRs follow resolution of spinal shock. In a neoplastic lesion, hyperactive DTRs gradually replace normal DTRs. Other signs and symptoms are paralysis and sensory loss below the level of the lesion, urine retention and overflow incontinence, and alternating constipation and diarrhea. A lesion above T6 may also produce autonomic hyperreflexia with diaphoresis and flushing above the level of the lesion, a headache, nasal congestion, nausea, increased blood pressure, and bradycardia.

- Stroke. A stroke that affects the origin of the corticospinal tracts causes the sudden onset of hyperactive DTRs on the side opposite the lesion. The patient may also have unilateral paresis or paralysis, anesthesia, visual field deficits, spasticity, and a positive Babinski’s reflex.

- Tetanus. With tetanus, the sudden onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs accompanies tachycardia, diaphoresis, a low-grade fever, painful and involuntary muscle contractions, trismus (lockjaw), and risus sardonicus (a masklike grin).

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests to evaluate hyperactive DTRs. These may include laboratory tests for serum calcium, magnesium, and ammonia levels, spinal X-rays, magnetic resonance imaging, a computed tomography scan, lumbar puncture, and myelography.

If motor weakness accompanies hyperactive DTRs, perform or encourage range-of-motion exercises to preserve muscle integrity and prevent deep vein thrombosis. Also, reposition the patient frequently, provide a special mattress, massage his back, and ensure adequate nutrition to prevent skin breakdown. Administer a muscle relaxant and sedative to relieve severe muscle contractions. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment on hand. Provide a quiet, calm atmosphere to decrease neuromuscular excitability. Assist with activities of daily living, and provide emotional support.

Patient Counseling

Explain to the caregiver the procedures and treatments the patient may need. Discuss safety measures, and provide emotional support.

Pediatric Pointers

Hyperreflexia may be a normal sign in neonates. After age 6, reflex responses are similar to those of adults. When testing DTRs in small children, use distraction techniques to promote reliable results.

Cerebral palsy commonly causes hyperactive DTRs in children. Reye’s syndrome causes generalized hyperactive DTRs in stage II; in stage V, DTRs are absent. Adult causes of hyperactive DTRs may also appear in children.

REFERENCES

Kluding, P. M., Dunning, K., O’Dell, M. W., Wu, S. S., Ginosin, J., Feld, J., & McBride, K. (2013). Foot drop stimulation versus ankle foot orthosis after stroke: 30-week outcomes. Stroke, 44(6), 1660–1669.

Ring, H., Treger, I., Gruendlinger, L., & Hausdorff, J. M. (2009). Neuroprosthesis for foot drop compared with an ankle-foot orthosis: Effects on postural control during walking. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease, 18(1), 41–47.

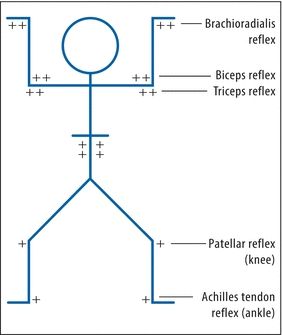

Deep Tendon Reflexes, Hypoactive

A hypoactive deep tendon reflex (DTR) is an abnormally diminished muscle contraction that occurs in response to a sudden stretch induced by sharply tapping the muscle’s tendon of insertion. It may be graded as minimal (+) or absent (0). Symmetrically reduced (+) reflexes may be normal.

Normally, a DTR depends on an intact receptor, an intact sensory-motor nerve fiber, an intact neuromuscular-glandular junction, and a functional synapse in the spinal cord. Hypoactive DTRs may result from damage to the reflex arc involving the specific muscle, the peripheral nerve, the nerve roots, or the spinal cord at that level. Hypoactive DTRs are an important sign of many disorders, especially when they appear with other neurologic signs and symptoms. (See Documenting Deep Tendon Reflexes.)

History and Physical Examination

After eliciting hypoactive DTRs, obtain a thorough history from the patient or a family member. Have him describe current signs and symptoms in detail. Then, take a family and drug history.

Next, evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness. Test motor function in his limbs, and palpate for muscle atrophy or increased mass. Test sensory function, including pain, touch, temperature, and vibration sense. Ask about paresthesia. To observe gait and coordination, have the patient take several steps. To check for Romberg’s sign, ask him to stand with his feet together and his eyes closed. During conversation, evaluate speech. Check for signs of vision or hearing loss. Abrupt onset of hypoactive DTRs accompanied by muscle weakness may occur with life-threatening Guillain-Barré syndrome, botulism, or spinal cord lesions with spinal shock.

Look for autonomic nervous system effects by taking vital signs and monitoring for increased heart rate and blood pressure. Also, inspect the skin for pallor, dryness, flushing, or diaphoresis. Auscultate for hypoactive bowel sounds, and palpate for bladder distention. Ask about nausea, vomiting, constipation, and incontinence.

Documenting Deep Tendon Reflexes

Record the patient’s deep tendon reflex (DTR) scores by drawing a stick figure and entering the grades on this scale at the proper location. The figure shown here indicates hypoactive DTRs in the legs; other reflexes are normal.

KEY:

0 = absent

+ = hypoactive (diminished)

++ = normal

+++ = brisk (increased)

++++ = hyperactive (clonus may be present)

Medical Causes

- Botulism. With botulism, generalized hypoactive DTRs accompany progressive descending muscle weakness. Initially, the patient usually complains of blurred and double vision and, occasionally, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. Other early bulbar findings include vertigo, hearing loss, dysarthria, and dysphagia. The patient may have signs of respiratory distress and severe constipation marked by hypoactive bowel sounds.

- Eaton-Lambert syndrome. Eaton-Lambert syndrome produces generalized hypoactive DTRs. Early signs include difficulty rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and walking. The patient may complain of achiness, paresthesia, and muscle weakness that’s most severe in the morning. Weakness improves with mild exercise and worsens with strenuous exercise.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome. Guillain-Barré syndrome causes bilateral hypoactive DTRs that progress rapidly from hypotonia to areflexia in several days. This disorder typically causes muscle weakness that begins in the legs and then extends to the arms and, possibly, to the trunk and neck muscles. Occasionally, weakness may progress to total paralysis. Other signs and symptoms include cranial nerve palsies, pain, paresthesia, and signs of brief autonomic dysfunction, such as sinus tachycardia or bradycardia, flushing, fluctuating blood pressure, and anhidrosis or episodic diaphoresis.

Usually, muscle weakness and hypoactive DTRs peak in severity within 10 to 14 days, and then, symptoms begin to clear. However, in severe cases, residual hypoactive DTRs and motor weakness may persist.

- Peripheral neuropathy. Characteristic of end-stage diabetes mellitus, renal failure, and alcoholism and as an adverse effect of various medications, peripheral neuropathy results in progressive hypoactive DTRs. Other effects include motor weakness, sensory loss, paresthesia, tremors, and possible autonomic dysfunction, such as orthostatic hypotension and incontinence.

- Polymyositis. With polymyositis, hypoactive DTRs accompany muscle weakness, pain, stiffness, spasms and, possibly, increased size or atrophy. These effects are usually temporary; their location varies with the affected muscles.

- Spinal cord lesions. Spinal cord injury or complete transection produces spinal shock, resulting in hypoactive DTRs (areflexia) below the level of the lesion. Associated signs and symptoms include quadriplegia or paraplegia, flaccidity, a loss of sensation below the level of the lesion, and dry, pale skin. Also characteristic are urine retention with overflow incontinence, hypoactive bowel sounds, constipation, and genital reflex loss. Hypoactive DTRs and flaccidity are usually transient; reflex activity may return within several weeks.

- Syringomyelia. Permanent bilateral hypoactive DTRs occur early in syringomyelia, which is a slowly progressive disorder. Other signs and symptoms include muscle weakness and atrophy; loss of sensation, usually extending in a capelike fashion over the arms, shoulders, neck, back, and occasionally the legs; deep, boring pain (despite analgesia) in the limbs; and signs of brain stem involvement (nystagmus, facial numbness, unilateral vocal cord paralysis or weakness, and unilateral tongue atrophy). It’s more common in males than in females.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Barbiturates and paralyzing drugs, such as pancuronium and curare, may cause hypoactive DTRs.

Special Considerations

Help the patient perform his daily activities. Try to strike a balance between promoting independence and ensuring his safety. Encourage him to walk with assistance. Make sure personal care articles are within easy reach, and provide an obstacle-free course from his bed to the bathroom.

If the patient has sensory deficits, protect him from injury from heat, cold, or pressure. Test his bath water, and reposition him frequently, ensuring a soft, smooth bed surface. Keep his skin clean and dry to prevent breakdown. Perform or encourage range-of-motion exercises. Also, encourage a balanced diet with plenty of protein and adequate hydration.

Patient Counseling

Teach skills that can help with independence in daily life. Discuss safety measures, including walking with assistance.

Pediatric Pointers

Hypoactive DTRs commonly occur in patients with muscular dystrophy, Friedreich’s ataxia, syringomyelia, and spinal cord injury. They also accompany progressive muscular atrophy, which affects preschoolers and adolescents.

Use distraction techniques to test DTRs; assess motor function by watching the infant or child at play.

REFERENCES

Born-Frontsberg, E., Reincke, M., Rump, L. C., Hahner, S., Diederich, S., Lorenz, R., … Quinkler, M.; Participants of the German Conn’s Registry. (2009). Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular comorbidities of hypokalemic and normokalemic primary aldosteronism: Results of the German Conn’s Registry. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 94(4), 1125–1130.

Krantz, M. J., Martin, J., Stimmel, B., Mehta, D., & Haigney, M. C. (2009). QTc interval screening in methadone treatment. Annals of Internal Medicine, 150, 387–395.

Depression

Depression is a mood disturbance characterized by feelings of sadness, despair, and loss of interest or pleasure in activities. These feelings may be accompanied by somatic complaints, such as changes in appetite, sleep disturbances, restlessness or lethargy, and decreased concentration. Thoughts of injuring one’s self, death, or suicide may also occur.

Clinical depression must be distinguished from “the blues,” periodic bouts of dysphoria that are less persistent and severe than the clinical disorder. The criterion for major depression is one or more episodes of depressed mood, or decreased interest or the ability to take pleasure in all or most activities, lasting at least 2 weeks.

Major depression affects approximately 20.9 million (9.5%) Americans in a given year. Approximately 12 million women (12%), 6 million men (7%), and 3 million adolescents (4%) experience depression each year. It affects all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, and it is twice as common in women as in men. It is the leading cause of disability of women and men of all ages in the United States and worldwide. Depression has numerous causes, including genetic and family history, medical and psychiatric disorders, and the use of certain drugs. It can also occur in the postpartum period. A complete psychiatric and physical examination should be conducted to exclude possible medical causes.

History and Physical Examination

During the examination, determine how the patient feels about herself, her family, and her environment. Your goal is to explore the nature of her depression, the extent to which other factors affect it, and her coping mechanisms and their effectiveness. Begin by asking what’s bothering her. How does her current mood differ from her usual mood? Then, ask her to describe the way she feels about herself. What are her plans and dreams? How realistic are they? Is she generally satisfied with what she has accomplished in her work, relationships, and other interests? Ask about changes in her social interactions, sleep patterns, appetite, normal activities, or ability to make decisions and concentrate. Determine patterns of drug and alcohol use. Listen for clues that she may be suicidal. (See Suicide: Caring for the High-Risk Patient.)

Ask the patient about her family — its patterns of interaction and characteristic responses to success and failure. What part does she feel she plays in her family life? Find out if other family members have been depressed and whether anyone important to the patient has been sick or has died in the past year. Finally, ask the patient about her environment. Has her lifestyle changed in the past month? Six months? Year? When she’s feeling blue, where does she go and what does she do to feel better? Find out how she feels about her role in the community and the resources that are available to her. Try to determine if she has an adequate support network to help her cope with her depression.

Suicide: Caring for the High-Risk Patient

One of the most common factors contributing to suicide is hopelessness, an emotion that’s common in a depressed patient. As a result, you’ll need to regularly assess her for suicidal tendencies.

The patient may provide specific clues about her intentions. For example, you may notice her talking frequently about death or the futility of life, concealing potentially harmful items (such as knives and belts), hoarding medications, giving away personal belongings, or getting her legal and financial affairs in order. If you suspect that a patient is suicidal, follow these guidelines:

- First, try to determine the patient’s suicide potential. Find out how upset she is. Does she have a simple, straightforward suicide plan that’s likely to succeed? Does she have a strong support system — family, friends, a therapist? A patient with low to moderate suicide potential is noticeably depressed but has a support system. She may have thoughts of suicide, but no specific plan. A patient with high suicide potential feels profoundly hopeless and has little or no support system. She thinks about suicide frequently and has a plan that’s likely to succeed.

- Next, observe precautions. Ensure the patient’s safety by removing objects she could use to harm herself, such as knives, scissors, razors, belts, electric cords, shoelaces, and drugs. Know her whereabouts and what she’s doing at all times; this may require one-on-one surveillance. Place the patient in a room that’s close to the nursing station, or ensure that a staff member is assigned to stay with her at all times. Always have someone accompany her when she leaves the unit.

- Be alert for in-hospital suicide attempts, which typically occur when there’s a low staff-to-patient ratio — between shifts, during evening and night shifts, or when a critical event, such as a code, draws attention away from the patient.

- Finally, arrange for follow-up counseling. Recognize suicidal ideation and behavior as a desperate cry for help. Contact a mental health professional for a referral.

CULTURAL CUE

CULTURAL CUE

Patients who don’t speak English fluently may have difficulty communicating their feelings and thoughts. Consider using someone outside the family as an interpreter to allow the patient to express her feelings more freely.

Medical Causes

- Organic disorders. Various organic disorders and chronic illnesses produce mild, moderate, or severe depression. Among these are metabolic and endocrine disorders, such as hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and diabetes; infectious diseases, such as influenza, hepatitis, and encephalitis; degenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and multi-infarct dementia; and neoplastic disorders such as cancer.

- Psychiatric disorders. Affective disorders are typically characterized by abrupt mood swings from depression to elation (mania) or by prolonged episodes of either mood. In fact, severe depression may last for weeks. More moderate depression occurs in cyclothymic disorders and usually alternates with moderate mania. Moderate depression that’s more or less constant over a 2-year period typically results from dysthymic disorders. Also, chronic anxiety disorders, such as panic and obsessive-compulsive disorder, may be accompanied by depression.

Other Causes

- Alcohol abuse. Long-term alcohol use, intoxication, or withdrawal commonly produces depression.

- Drugs. Various drugs cause depression as an adverse effect. Among the more common are barbiturates; chemotherapeutic drugs, such as asparaginase; anticonvulsants, such as diazepam; and antiarrhythmics, such as disopyramide. Other depression-inducing drugs include centrally acting antihypertensives, such as reserpine (common in high dosages), methyldopa, and clonidine; beta-adrenergic blockers, such as propranolol; levodopa; indomethacin; cycloserine; corticosteroids; and hormonal contraceptives.

- Postpartum period. Although the cause hasn’t been proved, depression occurs in about 1 in every 2,000 to 3,000 pregnancies and is characterized by various symptoms. Symptoms range from mild postpartum blues to an intense, suicidal, depressive psychosis.

Special Considerations

Caring for a depressed patient takes time, tact, and energy. It also requires an awareness of your own vulnerability to feelings of despair that can stem from interacting with a depressed patient. Help the patient set realistic goals; encourage her to promote feelings of self-worth by asserting her opinions and making decisions. Try to determine her suicide potential, and take steps to help ensure her safety. The patient may require close surveillance to prevent a suicide attempt.

Make sure that the patient receives adequate nourishment and rest, and keep her environment free from stress and excessive stimulation. Arrange for ordered diagnostic tests to determine if her depression has an organic cause, and administer prescribed drugs. Also arrange for follow-up counseling, or contact a mental health professional for a referral.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient about depression; emphasize that effective methods are available to relieve symptoms. Reassure the patient that she can help to ease depression by expressing her feelings, engaging in pleasurable activities, and improving her grooming and hygiene. Stress the importance of compliance with antidepressant medications, and review adverse reactions.

Pediatric Pointers

Because emotional lability is normal in adolescence, depression can be difficult to assess and diagnose in teenagers. Clues to underlying depression may include somatic complaints, sexual promiscuity, poor grades, and alcohol or drug abuse.

Using a family systems model usually helps determine the cause of depression in adolescents. After family roles are determined, family therapy or group therapy with peers may help the patient overcome her depression. In severe cases, an antidepressant may be required.

Geriatric Pointers

Elderly patients typically present with physical complaints, somatic complaints, agitation, or changes in intellectual functioning (memory impairment), making the diagnosis of depression difficult. Depressed older adults at highest risk for suicide are those who are aged 85 and older, have low self-esteem, and need to be in control. Even a frail nursing home resident with these characteristics may have the strength to kill herself.

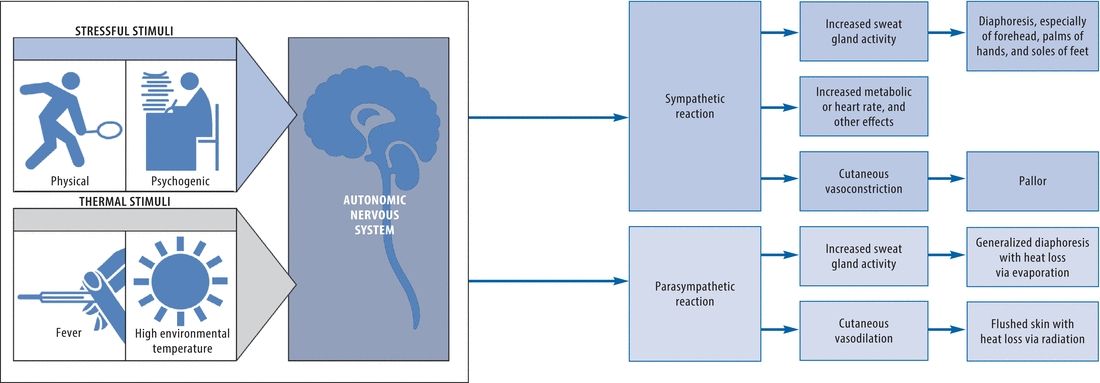

Diaphoresis

Diaphoresis is profuse sweating — at times, amounting to more than 1 L of sweat per hour. This sign represents an autonomic nervous system response to physical or psychogenic stress or to a fever or high environmental temperature. When caused by stress, diaphoresis may be generalized or limited to the palms, soles, and forehead. When caused by a fever or high environmental temperature, it’s usually generalized.

Diaphoresis usually begins abruptly and may be accompanied by other autonomic system signs, such as tachycardia and increased blood pressure. (See When Diaphoresis Spells Crisis, page 230.) However, this sign also varies with age because sweat glands function immaturely in infants and are less active in elderly patients. As a result, patients in these age groups may fail to display diaphoresis associated with its common causes. Intermittent diaphoresis may accompany chronic disorders characterized by a recurrent fever; isolated diaphoresis may mark an episode of acute pain or fever. Night sweats may characterize intermittent fever because body temperature tends to return to normal between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m. before rising again. (Temperature is usually lowest around 6 a.m.)

When caused by a high external temperature, diaphoresis is a normal response. Acclimatization usually requires several days of exposure to high temperatures; during this process, diaphoresis helps maintain normal body temperature. Diaphoresis also commonly occurs during menopause, preceded by a sensation of intense heat (a hot flash). Other causes include exercise or exertion that accelerates metabolism, creating internal heat, and mild to moderate anxiety that helps initiate the fight-or-flight response. (See Understanding Diaphoresis, pages 232 and 233.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS When Diaphoresis Spells Crisis

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS When Diaphoresis Spells Crisis

Diaphoresis is an early sign of certain life-threatening disorders. These guidelines will help you promptly detect such disorders and intervene to minimize harm to the patient.

HYPOGLYCEMIA

If you observe diaphoresis in a patient who complains of blurred vision, ask him about increased irritability and anxiety. Has he been unusually hungry lately? Does he have tremors? Take the patient’s vital signs, noting hypotension and tachycardia. Then, ask about a history of type 2 diabetes or antidiabetic therapy. If you suspect hypoglycemia, evaluate the patient’s blood glucose level using a glucose reagent strip, or send a serum sample to the laboratory. Administer I.V. glucose 50%, as ordered, to return the patient’s glucose level to normal. Monitor his vital signs and cardiac rhythm. Ensure a patent airway, and be prepared to assist with breathing and circulation if necessary.

HEATSTROKE

If you observe profuse diaphoresis in a weak, tired, and apprehensive patient, suspect heatstroke, which can progress to circulatory collapse. Take his vital signs, noting a normal or subnormal temperature. Check for ashen gray skin and dilated pupils. Was the patient recently exposed to high temperatures and humidity? Was he wearing heavy clothing or performing strenuous physical activity at the time? Also, ask if he takes a diuretic, which interferes with normal sweating.

Then, take the patient to a cool room, remove his clothing, and use a fan to direct cool air over his body. Insert an I.V. line, and prepare for electrolyte and fluid replacement. Monitor him for signs of shock. Check his urine output carefully along with other sources of output (such as tubes, drains, and ostomies).

AUTONOMIC HYPERREFLEXIA

If you observe diaphoresis in a patient with a spinal cord injury above T6 or T7, ask if he has a pounding headache, restlessness, blurred vision, or nasal congestion. Take the patient’s vital signs, noting bradycardia and extremely elevated blood pressure. If you suspect autonomic hyperreflexia, quickly rule out its common complications. Examine the patient for eye pain associated with intraocular hemorrhage and for facial paralysis, slurred speech, or limb weakness associated with intracerebral hemorrhage.

Quickly reposition the patient to remove any pressure stimuli. Also, check for a distended bladder or fecal impaction. Remove any kinks from the urinary catheter if necessary, or administer a suppository or manually remove impacted feces. If you can’t locate and relieve the causative stimulus, start an I.V. line. Prepare to administer hydralazine for hypertension.

MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION OR HEART FAILURE

If the diaphoretic patient complains of chest pain and dyspnea or has arrhythmias or electrocardiogram changes, suspect a myocardial infarction or heart failure. Connect the patient to a cardiac monitor, ensure a patent airway, and administer supplemental oxygen. Start an I.V. line, and administer an analgesic. Be prepared to begin emergency resuscitation if cardiac or respiratory arrest occurs.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient is diaphoretic, quickly rule out the possibility of a life-threatening cause. Begin the history by having the patient describe his chief complaint. Then, explore associated signs and symptoms. Note general fatigue and weakness. Does the patient have insomnia, headache, and changes in vision or hearing? Is he often dizzy? Does he have palpitations? Ask about pleuritic pain, a cough, sputum, difficulty breathing, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and altered bowel or bladder habits. Ask the female patient about amenorrhea and any changes in her menstrual cycle. Is she menopausal? Ask about paresthesia, muscle cramps or stiffness, and joint pain. Has she noticed any changes in elimination habits? Note weight loss or gain. Has the patient had to change her glove or shoe size lately?

Complete the history by asking about travel to tropical countries. Note recent exposure to high environmental temperatures or pesticides. Did the patient recently experience an insect bite? Check for a history of partial gastrectomy or of drug or alcohol abuse. Finally, obtain a thorough drug history.

Next, perform a physical examination. First, determine the extent of diaphoresis by inspecting the trunk and extremities as well as the palms, soles, and forehead. Also, check the patient’s clothing and bedding for dampness. Note whether diaphoresis occurs during the day or at night. Observe the patient for flushing, an abnormal skin texture or lesions, and an increased amount of coarse body hair. Note poor skin turgor and dry mucous membranes. Check for splinter hemorrhages and Plummer’s nails (separation of the fingernail ends from the nail beds).

Then, evaluate the patient’s mental status and take his vital signs. Observe him for fasciculations and flaccid paralysis. Be alert for seizures. Note the patient’s facial expression, and examine the eyes for pupillary dilation or constriction, exophthalmos, and excessive tearing. Test visual fields. Also, check for hearing loss and for tooth or gum disease. Percuss the lungs for dullness, and auscultate for crackles, diminished or bronchial breath sounds, and increased vocal fremitus. Look for decreased respiratory excursion. Palpate for lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly.

Medical Causes

- Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Night sweats may be an early feature, occurring either as a manifestation of the disease itself or secondary to an opportunistic infection. The patient also displays a fever, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, anorexia, dramatic and unexplained weight loss, diarrhea, and a persistent cough.

- Acromegaly. With acromegaly, diaphoresis is a sensitive gauge of disease activity, which involves the hypersecretion of growth hormone and an increased metabolic rate. The patient has a hulking appearance with an enlarged supraorbital ridge and thickened ears and nose. Other signs and symptoms include warm, oily, thickened skin; enlarged hands, feet, and jaw; joint pain; weight gain; hoarseness; and increased coarse body hair. Increased blood pressure, a severe headache, and visual field deficits or blindness may also occur.

Understanding Diaphoresis

- Anxiety disorders. Acute anxiety characterizes panic, whereas chronic anxiety characterizes phobias, conversion disorders, obsessions, and compulsions. Whether acute or chronic, anxiety may cause sympathetic stimulation, resulting in diaphoresis. The diaphoresis is most dramatic on the palms, soles, and forehead and is accompanied by palpitations, tachycardia, tachypnea, tremors, and GI distress. Psychological signs and symptoms — fear, difficulty concentrating, and behavior changes — also occur.

- Autonomic hyperreflexia. Occurring after resolution of spinal shock in a spinal cord injury above T6, hyperreflexia causes profuse diaphoresis, a pounding headache, blurred vision, and dramatically elevated blood pressure. Diaphoresis occurs above the level of the injury, especially on the forehead, and is accompanied by flushing. Other findings include restlessness, nausea, nasal congestion, and bradycardia.

- Drug and alcohol withdrawal syndromes. Withdrawal from alcohol or an opioid analgesic may cause generalized diaphoresis, dilated pupils, tachycardia, tremors, and an altered mental status (confusion, delusions, hallucinations, agitation). Associated signs and symptoms include severe muscle cramps, generalized paresthesia, tachypnea, increased or decreased blood pressure and, possibly, seizures. Nausea and vomiting are common.

- Empyema. Pus accumulation in the pleural space leads to drenching night sweats and fever. The patient also complains of chest pain, a cough, and weight loss. Examination reveals decreased respiratory excursion on the affected side and absent or distant breath sounds.

- Heart failure. Typically, diaphoresis follows fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea, and tachycardia in patients with left-sided heart failure and jugular vein distention and a dry cough in patients with right-sided heart failure. Other features include tachypnea, cyanosis, dependent edema, crackles, a ventricular gallop, and anxiety.

- Heat exhaustion. Although heat exhaustion is marked by failure of heat to dissipate, it initially may cause profuse diaphoresis, fatigue, weakness, and anxiety. These signs and symptoms may progress to circulatory collapse and shock (confusion, a thready pulse, hypotension, tachycardia, and cold, clammy skin). Other features include an ashen gray appearance, dilated pupils, and a normal or subnormal temperature.

- Hodgkin’s disease. Especially in elderly patients, early features of Hodgkin’s disease may include night sweats, a fever, fatigue, pruritus, and weight loss. Usually, however, this disease initially causes painless swelling of a cervical lymph node. Occasionally, a Pel-Ebstein fever pattern is present — several days or weeks of fever and chills alternating with afebrile periods with no chills. Systemic signs and symptoms — such as weight loss, a fever, and night sweats — indicate a poor prognosis. Progressive lymphadenopathy eventually causes widespread effects, such as hepatomegaly and dyspnea.

- Hypoglycemia. Rapidly induced hypoglycemia may cause diaphoresis accompanied by irritability, tremors, hypotension, blurred vision, tachycardia, hunger, and loss of consciousness.

- Infective endocarditis (subacute). Generalized night sweats occur early with infective endocarditis. Accompanying signs and symptoms include an intermittent low-grade fever, weakness, fatigue, weight loss, anorexia, and arthralgia. A sudden change in a murmur or the discovery of a new murmur is a classic sign. Petechiae and splinter hemorrhages are also common.

- Lung abscess. Drenching night sweats are common with lung abscess. Its chief sign, however, is a cough that produces copious purulent, foul-smelling, and typically bloody sputum. Associated findings include a fever with chills, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, a headache, malaise, clubbing, tubular or amphoric breath sounds, and dullness on percussion.

- Malaria. Profuse diaphoresis marks the third stage of paroxysmal malaria; the first two stages are chills (first stage) and a high fever (second stage). A headache, arthralgia, and hepatosplenomegaly may also occur. In the benign form of malaria, these paroxysms alternate with periods of well-being. The severe form may progress to delirium, seizures, and coma.

- Myocardial infarction (MI). Diaphoresis usually accompanies acute, substernal, radiating chest pain in MI, a life-threatening disorder. Associated signs and symptoms include anxiety, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, an irregular pulse, blood pressure changes, fine crackles, pallor, and clammy skin.

- Pheochromocytoma. Pheochromocytoma commonly produces diaphoresis, but its cardinal sign is persistent or paroxysmal hypertension. Other effects include a headache, palpitations, tachycardia, anxiety, tremors, pallor, flushing, paresthesia, abdominal pain, tachypnea, nausea, vomiting, and orthostatic hypotension.

- Pneumonia. Intermittent, generalized diaphoresis accompanies a fever and chills in patients with pneumonia. They complain of pleuritic chest pain that increases with deep inspiration. Other features are tachypnea, dyspnea, a productive cough (with scant and mucoid or copious and purulent sputum), a headache, fatigue, myalgia, abdominal pain, anorexia, and cyanosis. Auscultation reveals bronchial breath sounds.

- Tetanus. Tetanus commonly causes profuse sweating accompanied by a low-grade fever, tachycardia, and hyperactive deep tendon reflexes. Early restlessness and pain and stiffness in the jaw, abdomen, and back progress to spasms associated with lockjaw, risus sardonicus, dysphagia, and opisthotonos. Laryngospasm may result in cyanosis or sudden death by asphyxiation.

- Thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis commonly produces diaphoresis accompanied by heat intolerance, weight loss despite increased appetite, tachycardia, palpitations, an enlarged thyroid, dyspnea, nervousness, diarrhea, tremors, Plummer’s nails and, possibly, exophthalmos. Gallops may also occur.

- Tuberculosis (TB). Although many patients with primary infection are asymptomatic, TB may cause night sweats, a low-grade fever, fatigue, weakness, anorexia, and weight loss. In reactivation, a productive cough with mucopurulent sputum, occasional hemoptysis, and chest pain may be present.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Sympathomimetics, certain antipsychotics, thyroid hormones, corticosteroids, and antipyretics may cause diaphoresis. Aspirin and acetaminophen poisoning also cause this sign.

- Dumping syndrome. The result of rapid emptying of gastric contents into the small intestine after partial gastrectomy, this syndrome causes diaphoresis, palpitations, profound weakness, epigastric distress, nausea, and explosive diarrhea. This syndrome occurs soon after eating.

- Pesticide poisoning. Among the toxic effects of pesticides are diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, blurred vision, miosis, and excessive lacrimation and salivation. The patient may display fasciculations, muscle weakness, and flaccid paralysis. Signs of respiratory depression and coma may also occur.

Special Considerations

After an episode of diaphoresis, sponge the patient’s face and body and change wet clothes and sheets. To prevent skin irritation, dust skin folds in the groin and axillae and under pendulous breasts with cornstarch, or tuck gauze or cloth into the folds. Encourage regular bathing.

Replace fluids and electrolytes. Regulate infusions of I.V. saline or lactated Ringer’s solution, and monitor urine output. Encourage oral fluids high in electrolytes such as sports drinks. Enforce bed rest, and maintain a quiet environment. Keep the patient’s room temperature moderate to prevent additional diaphoresis.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as blood tests, cultures, chest X-rays, immunologic studies, biopsy, a computed tomography scan, and audiometry. Monitor the patient’s vital signs, including temperature.

Patient Counseling

Explain the disease process and proper skin care. Discuss the importance of fluid replacement and how to make sure fluid intake is adequate.

Pediatric Pointers

Diaphoresis in children commonly results from environmental heat or overdressing; it’s usually most apparent around the head. Other causes include drug withdrawal associated with maternal addiction, heart failure, thyrotoxicosis, and the effects of such drugs as antihistamines, ephedrine, haloperidol, and thyroid hormone.

Assess the child’s fluid status carefully. Some fluid loss through diaphoresis may precipitate hypovolemia more rapidly in a child than in an adult. Monitor input and output, weigh the child daily, and note the duration of each episode of diaphoresis.

Geriatric Pointers

Fever and night sweats, the hallmark of TB, may not occur in elderly patients, who instead may exhibit a change in activity or weight. Also, keep in mind that older patients may not exhibit diaphoresis because of a decreased sweating mechanism. For this reason, they’re at increased risk for developing heatstroke in high temperatures.

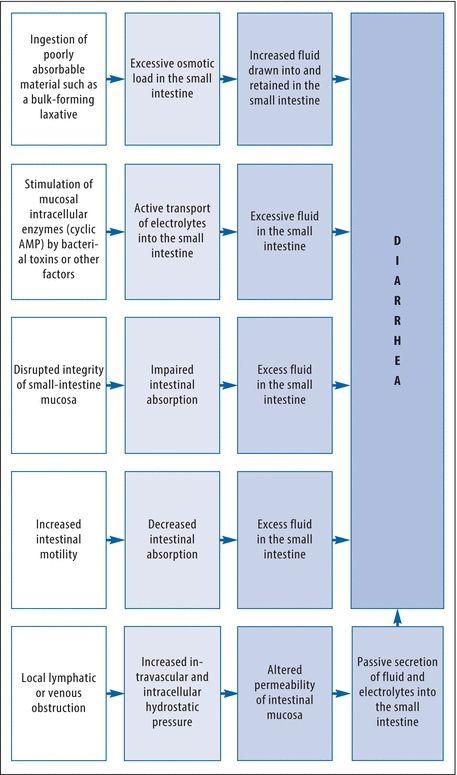

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is loose, watery stools. Usually a chief sign of an intestinal disorder, diarrhea is an increase in the volume of stools compared with the patient’s normal bowel habits. It varies in severity and may be acute or chronic. Acute diarrhea may result from acute infection, stress, fecal impaction, or the effect of a drug. Chronic diarrhea may result from chronic infection, obstructive and inflammatory bowel disease, malabsorption syndrome, an endocrine disorder, or GI surgery. Periodic diarrhea may result from food intolerance or from ingestion of spicy or high-fiber foods or caffeine.

One or more pathophysiologic mechanisms may contribute to diarrhea. (See What Causes Diarrhea?) The fluid and electrolyte imbalances it produces may precipitate life-threatening arrhythmias or hypovolemic shock.

What Causes Diarrhea?

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient’s diarrhea is profuse, check for signs of shock — tachycardia, hypotension, and cool, pale, clammy skin. If you detect these signs, place the patient in the supine position and elevate his legs 20 degrees. Insert an I.V. line for fluid replacement. Monitor him for electrolyte imbalances, and look for an irregular pulse, muscle weakness, anorexia, and nausea and vomiting. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment handy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree