Chapter 42 Using open and distance learning to develop clinical reasoning skills

INTRODUCTION

Health sciences education is a distributed process with students located in different sites at different times. Consistency, quality assurance and cost-effectiveness of education are of paramount importance and this presents challenges to the profession. Distance learning demonstrates its strengths in such circumstances and many would believe that this will be the next paradigm shift in health sciences education, democratizing educational provision, improving access to the resources of more advantaged schools and building transparency and accountability into the process of educational development.

WHAT IS DISTANCE LEARNING?

Health sciences education is, in practice, a distributed system. Clinical practice is central to training and so students and trainees learn wherever there are patients. And patients are distributed across the community and within hospitals. Far from wondering how distance learning can teach medicine, the more relevant question is: How can health sciences education be conducted effectively without distance learning techniques? As it is used in the UK Open University, which was the world’s first distance learning university, distance learning may be defined as: individual study of specially prepared learning materials, usually print and sometimes e-learning, supplemented by integrated learning resources, other learning experiences, including face-to-face teaching and practical experience, feedback on learning and student support.

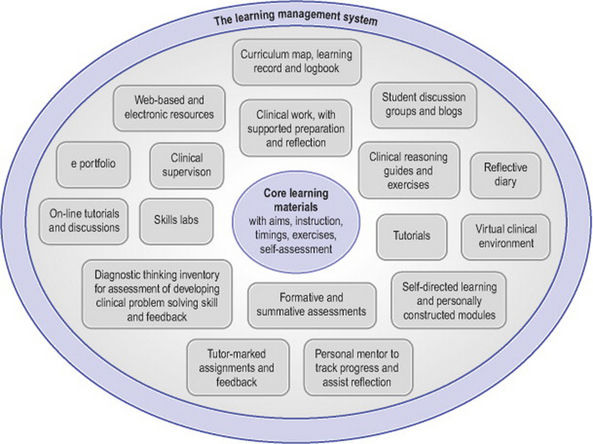

Distance learning provides a rich and planned experience for learners that is quality assured, flexible and cost-effective. Often distance learning is equated with e-learning. But it is much more, as Figure 42.1 shows.

Figure 42.1 The components of a distance learning programme, organized within a learning management system

Firstly, there is a learning management system which, these days, is usually the electronic framework in which all the other elements hang. Information technology is then called a virtual learning environment (VLE). But it could equally be a management system based on central office functions if computing power is unavailable. Within this system, students can be offered a variety of carefully planned, developed and quality assured elements (Grant 2001) which ensure curriculum coverage. Electronic (or print) elements can be:

Face-to-face elements can include tutorials, clinical supervision, skills labs, residential and elective events and assessments. These elements require careful planning and integration but many, such as the unpublished clinical problem solving exercises which we use as the basis of current workshops, are already available in print form. Distance learning components, then, can be divided into three main types, each of which has its role to play: (a) traditional paper-based approach; (b) electronic learning (e-learning); and (c) mobile learning (m-learning using, for example, hand-held computers for continuing professional development, as described by Walton et al 2005).

The medium can offer a rich virtual learning environment made up of blogs (open web-log diaries) and wikis (participant-led glossaries), structured conferencing, instant messaging and e-portfolios. So e-learning is more than structured course materials. E-learning itself can also replicate the less formal interactions between students and teachers, as McConnell (2006) explains: ‘students and teachers do “meet”; they meet in virtual learning environments (VLEs) through the use of computers’ (p. 1).

However, although students are enthusiastic about e-learning, they also wish to retain some printed text which offers active learning, problem solving and feedback (Clarke et al 2005, Donnelly & Agius 2005, Markova et al 2005, Urquhart et al 2002). And we should not forget that there is still the concern that having learning materials exclusively on-line or reliant on computer-based software might penalize those who cannot afford or access computers, those who are in remote areas with only unreliable dial-up connections, and those who are not computer literate. But distance learning allows the use of print as well as more technology-based media, and it may well be that different modalities are equally as effective in achieving learning objectives associated with clinical reasoning (Lysaght & Bent 2005).

CAN DISTANCE LEARNING TEACH CLINICAL MEDICINE AND HEALTH SCIENCES?

But the health professions are different from these other disciplines in some fundamental ways:

Feasibility studies conducted in the Open University and more recently in other universities have shown quite clearly that distance learning is a powerful support to these complex processes. Figure 42.2 shows some of the potential applications of distance learning techniques in a clinical setting.

MODELS AND DESCRIPTIONS OF THE CLINICAL PROBLEM SOLVING PROCESS

To design and implement distance education to teach clinical problem solving we need to understand this phenomenon. The literature provides many models and descriptions of clinical reasoning and problem solving, as discussed in previous chapters. Researchers have chosen either to describe or to model the clinical problem-solving process. Descriptions are based in cognitive psychology and try to portray what is going on inside the head of the clinician, whereas models tend to find another way of representing the process, usually in terms of statistical or algorithmic frameworks. But teaching based on statistical or algorithmic models such as Bayes’ theorem (Gill et al 2005) can only ask students to use a formula which will overlay their own cognitive processing of the data. We therefore propose to advocate strategies that will help students to enhance their thinking processes by preparing for and reflecting on experience.

DESCRIPTIONS BASED ON COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree