The big picture165

12.2 Upper thorax, brachial plexus, pectoral girdle, scapula

166

12.5 Arm, elbow, cubital fossa, supination, pronation

176

12.6 Flexor compartment of the forearm, carpus, carpal tunnel

180

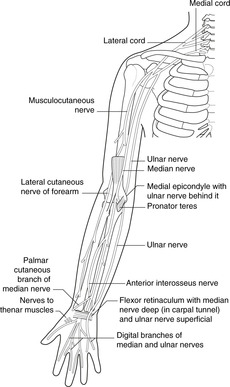

12.8 Innervation, nerve testing, surface anatomy

190

Beware!

‘Arm’ means upper limb from shoulder to elbow, not the entire upper limb. ‘Forearm’ means upper limb from elbow to wrist.

Radial, ulnar, lateral, medial

Particularly in the forearm and hand, the terms radial and ulnar are used in preference to lateral and medial (respectively). This avoids confusion which may arise depending upon the position of the hand. The thumb is always on the radial side, and the little finger always on the ulnar side.

12.1. The big picture

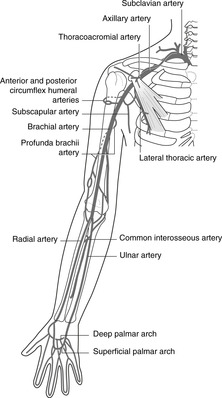

Arterial blood to the upper limb comes from the subclavian and axillary arteries.

• Subclavian: extends from its origin to the lateral border of the first rib.

• Axillary: extends from the lateral border of the first rib to the lateral border of teres major muscle.

• Brachial: extends from the lateral border of teres major to the cubital fossa, where it bifurcates to give:

• Radial (lateral) and ulnar (medial) arteries. These pass down the respective sides of the forearm to the hand where they form two anastomoses in the palm:

• Superficial and deep palmar arterial arches.

Venous blood drains to the subclavian veins, thence to the brachiocephalic veins and the superior vena cava.

Superficial veins are immediately subcutaneous, superficial to the deep fascia which surrounds the muscles, bones and other deeper structures like a sleeve. These veins are visible or palpable (unless the patient is very fat) and are easily accessible for venepuncture. The pattern of superficial veins is very variable: you need only bother with:

• the dorsal venous arch on the back of the hand, very variable pattern, from which arise:

– the cephalic vein: lateral side of the upper limb to the deltopectoral groove between the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles

– the basilic vein: medial side of the upper limb, piercing the deep fascia as it approaches the axilla and contributing to the formation of the axillary vein

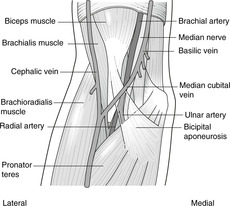

– veins in front of the elbow (often injection sites): these are very variable, but there is usually a median cubital vein (see

Fig. 12.20 and look at your own).

• Deep veins, within the fascial sleeve, accompany the arteries and are thus named venae comitantes (Latin: accompanying veins). They receive connections from the superficial veins and in the axillary region unite to form the axillary vein, which then becomes the subclavian.

Lymph

All lymph drains to axillary nodes.

• From the radial side of the upper limb, lymph drains alongside the cephalic vein to the deltopectoral (infraclavicular) nodes, outposts of the axillary nodes to which they drain. The deltopectoral nodes are the only lymph nodes on this pathway and are the first nodes to be involved in, for example, an infection of the thumb.

• From the ulnar side of the upper limb, lymph drains alongside the basilic vein to the epitrochlear nodes, just above the elbow, thence to the axillary nodes.

Nerves

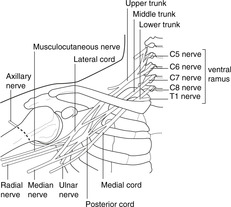

All nerves come from the ventral rami of C5, 6, 7, 8 and T1, which form the brachial plexus.

Dermatomes and myotomes. In the body wall, the muscles and skin supplied by one segmental nerve are roughly coexistent. This is not so in the limbs. The dermatomes (sensory) are shown in

Figure 6.6 (p. 36), but the muscles supplied by the same spinal segments are often far distant. For example, T1 dermatome is in the axilla, but muscles supplied by T1 are in the hand. An embryology book will explain why, but the ‘big picture’ is that dermatomes are arranged roughly from cephalic (above) to caudal (below) if you hold out your arm horizontally with the palms facing forwards, and the myotomes are arranged from proximal (C5 for shoulder movements) to distal (T1 for small muscles of the hand). See

Chapter 6, p. 31.

12.2. Upper thorax, brachial plexus, pectoral girdle, scapula

The subclavian, axillary and branchial arteries, together with their branches, supply the upper limb. Easily palpable pulses are the brachial, radial and ulnar. Upper limb nerves come from the brachial plexus formed by ventral rami of spinal nerves C5, 6, 7, 8 and T1. Extensor muscles and skin over the posterior aspect of the upper limb are supplied by the radial and axillary nerves and their branches. The principal nerves supplying flexor muscles and anterior skin are the median, ulnar and musculocutaneous. The clavicle and scapula articulate with the thorax at the sternoclavicular joint, and with each other at the acromioclavicular joint, diseases of both joints hindering upper limb movements.

You should:

• describe the main arterial tree of the upper limb, and the position of the brachial, radial and ulnar pulses

• explain the principles of venous and lymph drainage of the upper limb

• describe the formation, position and main branches of the brachial plexus

• describe the principal features of the clavicle and scapula, and understand the manner in which they move on the thorax.

Subclavian artery

This is divided into three parts by scalenus anterior muscle.

• Branches of first part (medial to scalenus anterior):

– internal thoracic: to supply breast, anterior chest wall, anterior abdominal wall, pericardium, diaphragm

– vertebral: to spinal cord, brain stem, brain

– thyrocervical trunk, which gives inferior thyroid, suprascapular (unimportant), transverse cervical (unimportant): to supply thyroid gland, upper scapular region and anterior neck.

• Branches of second part (behind scalenus anterior) and third part (between scalenus anterior and lateral border of first rib):

– branches are variable and unimportant, but include the costocervical trunk and dorsal scapular artery, the last named contributing to the scapular anastomosis (see later).

Subclavian pulse. The subclavian pulse is palpable above and behind the middle of the clavicle. The artery is deep to the vein here.

Axillary artery

This is divided into three parts by pectoralis minor muscle.

• Branches of first part (medial to pectoralis minor):

– supreme or highest thoracic (unimportant).

• Branches of second part (behind pectoralis minor):

– thoracoacromial: to upper chest and acromial region, breast

– lateral thoracic: to breast and chest.

• Branches of third part (between pectoralis minor and lateral border of teres major):

– subscapular: to scapular muscles, scapular anastomosis

– anterior circumflex humeral

– posterior circumflex humeral.

These last two may arise by a common trunk. They form an arterial circle round the surgical neck of the humerus (see

Fig. 12.9) and supply the neighbouring bone, muscles and shoulder joint.

Scapular anastomosis

The arterial anastomosis around the shoulder joint receives blood from branches of the subclavian and axillary arteries, and has connections with the intercostals. It may be involved in bypassing a blocked distal subclavian or proximal axillary artery, blood flowing retrogradely up the subscapular to reach the distal axillary; and in bypassing an aortic coarctation (see

Fig. 10.25, p. 88).

Veins

All veins from the upper limb, pectoral and scapular regions, together with the external jugular veins from the neck, drain into the subclavian vein. The only details worth committing to memory are:

• The cephalic vein penetrates the clavipectoral fascia (a fascial sheet between the clavicle and pectoralis minor muscle, occupying the deltopectoral triangle) to become deep before it joins the axillary vein. This is one place where central lines (catheters inserted into the heart) may be inserted.

• The subclavian vein is accessible for catheters, etc. just behind the middle of the clavicle. Aim the catheter downwards and medially: the vein is superficial here.

• The subclavian vein joins the internal jugular to form the brachiocephalic behind the sternoclavicular joint.

Brachial plexus and main branches (Fig. 12.2)

Roots and trunks

Roots of the plexus: ventral rami of C5–T1.

• The ventral rami of C5 and 6 join to form the upper trunk.

• The ventral rami of C8 and T1 join to form the lower trunk.

Branches of roots and trunks, in order of importance

• Long thoracic (supplies serratus anterior), from C5, 6, 7 roots.

• Suprascapular (supplies infra- and supraspinatus), upper trunk C5, 6.

• Dorsal scapular (supplies rhomboids), C5 root; nerve to subclavius, C5, 6 roots (don’t bother with either the nerve or the muscle).

Divisions, cords

Each trunk divides into an anterior and a posterior division, the divisions uniting to form cords as described. The cords are named by the position in respect to the axillary artery: posterior, lateral, medial.

Posterior cord and branches (Fig. 12.3)

Posterior divisions all unite to form the posterior cord, branches of which supply the posterior skin of the upper limb and all the extensor muscles. Its branches are:

• axillary, C5, 6: to deltoid muscle (shoulder abduction), skin over deltoid muscle

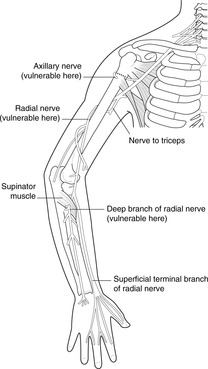

• radial, C5–T1: to all extensor muscles, posterior skin of entire upper limb

• other branches: subscapular nerves, thoracodorsal nerves: to posterior scapular muscles and latissimus dorsi.

Lateral cord and branches (Fig. 12.4)

The anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks unite to form the lateral cord. Its branches are:

• musculocutaneous nerve, C5, 6, 7: to elbow flexors and lateral skin of the forearm

• contribution to the median nerve (see below)

• lateral pectoral: to pectoral muscles (not important).

Median nerve, plexus position and variations

• The median nerve is formed from all roots, C5–T1. The contributions from the lateral and medial cords may unite within a short distance, or they may remain separate until well down the arm. It supplies most forearm flexors, the thenar muscles of the hand, and skin of the radial side of the palm of the hand.

• The brachial plexus is found at the top of the rib cage. It is behind and beneath the clavicle and first rib, and trauma or disease in the posterior triangle of the neck may damage the upper trunk.

• The plexus may arise from C4–8 (prefixed), or C5–T2 (postfixed).

Clavicle

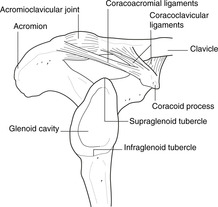

The only feature of note is the tuberosity near the lateral end, for the attachment of the coracoclavicular ligaments. The clavicle tends to fracture immediately medial to this ligamentous attachment (see later).

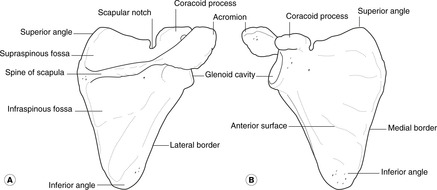

Scapula

• The anterior or costal surface is plain and is the subscapular fossa (sub- because it is ‘underneath’ in the quadruped).

• The posterior or dorsal surface is divided by the spine into the supraspinous and infraspinous fossas.

• The spine is prolonged laterally to form the acromion, which articulates with the clavicle.

• The glenoid fossa is the articular surface for the head of the humerus.

Movements and muscles of the pectoral girdle

Every time you move your upper limb, you move the clavicle and scapula. The joints that link them to the trunk are therefore important and disease of them will limit upper limb movement.

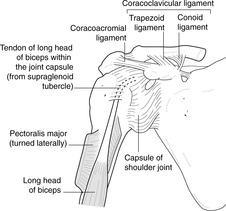

Joints and ligaments (Fig. 12.6)

Sternum–clavicle–scapula

• Sternoclavicular joint: synovial. Important relation: immediately posterior is the formation of the brachiocephalic vein from the subclavian and internal jugular veins. This joint sometimes disarticulates, the medial end of the clavicle appearing as a lump. It may or may not be painful, and often happens for no very obvious reason.

• Acromioclavicular joint: synovial.

• Coracoacromial ‘articulation’. A strong ligament.

• Coracoclavicular ‘articulation’. Strong ligaments, conoid and trapezoid, form an axis around which some rotation of the scapula on the clavicle (or vice versa) takes place, and the union is sufficiently strong for force transmitted up the arm from, say, a fall on the outstretched hand to fracture the clavicle medial to the attachment of the coracoclavicular ligament. The lateral portion of the fractured clavicle is displaced downwards by the weight of the upper limb.

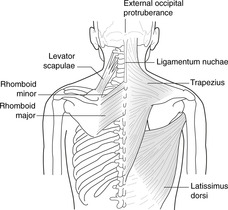

Trapezius. Attachments: external occipital protuberance, spines of cervical (through ligamentum nuchae) and thoracic vertebrae–clavicle, acromion and lateral part of spine of scapula. Upper fibres pass to the clavicle, acromion and lateral end of the spine; lower fibres pass to the medial end of the spine.

Nerve supply to muscles

Accessory (eleventh cranial) nerve. (See Neck, page 256.)

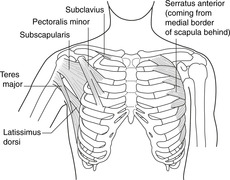

Serratus anterior. Attachments: medial border of scapula – upper eight ribs. This runs laterally and anteriorly from the medial border of the scapula, between the scapula and the rib cage. It is important in a quadruped since it is one of the muscles that suspends the trunk from the limbs. Because of the separate digitations to the eight ribs, the anterior border appears serrated, hence the name serratus. (Serratus posterior muscle: don’t even think about it.)

Long thoracic nerve (of Bell)

Levator scapulae. Attachments: C1–4 vertebrae – upper medial border of scapula.

Branches from C3, 4, 5 ventral rami. Unimportant

Rhomboids. Attachments: medial border of scapula – spines of thoracic vertebrae T2–5.

Dorsal scapular nerve

Pectoralis minor. Attachments: coracoid process–anterior aspect of ribs 3–5.

Pectoral nerves (details not necessary)

Latissimus dorsi. Attachments: thoracolumbar vertebrae and lumbar fascia–humerus. It is considered later, but a small portion of it attaches to the inferior angle of the scapula, and so it may be involved in scapular rotation.

Thoracodorsal nerve from posterior cord

Movements of the scapula

The scapula moves over the chest wall, but there are no distinct anatomical joints. Instead, muscles pull the scapula forward and backwards (protraction and retraction), and they rotate it so that the inferior angle moves laterally and up, and the superomedial angle medially and down.

• Protraction: serratus anterior, pectoralis minor.

• Retraction: trapezius (lower fibres), rhomboids (latissimus dorsi possibly).

• Rotation: trapezius (upper fibres), serratus anterior. Upper fibres of trapezius pull the acromioclavicular region superomedially, and the lower fibres of serratus anterior pull the inferior angle laterally and forwards. This means that the glenoid cavity faces upwards, and this movement is a necessary accompaniment of shoulder abduction (see later).

12.3. Shoulder region

The glenohumeral joint, an articulation between scapula and humerus, sacrifices stability for mobility. Movements in all planes are possible, ligaments and the rotator cuff muscles providing stability lacking in the bony conformation. These may be damaged giving rise to limitation of movement. Dislocations of the humeral head, or fractures of the surgical neck of the humerus, may damage the axillary nerve which supplies the principal shoulder abductor, deltoid.

You should:

• describe the surface anatomy of the shoulder region

• describe the principal features of the upper humerus and scapula

• list the main muscle groups producing shoulder movements, and their innervation

• describe how stability is provided at the joint, and the medical conditions that can arise.

Bones and ligaments

Scapula

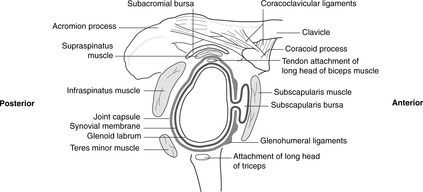

Glenoid fossa. This relatively shallow articular surface is made deeper by a circumferential lip of cartilage, the glenoid labrum. Above and below the fossa are two areas, the supra- and infraglenoid tubercles, to which the long heads of, respectively, biceps and triceps are attached.

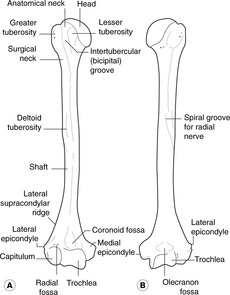

• Head. This articulates with the glenoid fossa of the scapula.

• Greater (lateral) and lesser (anteromedial) tuberosities provide attachments for muscles and are separated by the intertubercular sulcus or groove which, because it transmits the tendon of the long head of biceps is also known as the bicipital groove (the name used in this text).

• Surgical neck. This is important since it is a site of fracture and is related to the axillary nerve that passes from medial to lateral behind the surgical neck. It may be damaged in surgical neck fractures or by shoulder dislocations. The circumflex humeral arteries are also related to it.

• Deltoid tuberosity. This is a roughness just above midway down the lateral aspect of the humerus. Deltoid muscle is attached here.

• Spiral groove. You will see a ‘spiral’ impression running from the upper medial aspect of the bone, behind the shaft and appearing on the lower lateral aspect. This is formed by the attachments of triceps muscle, but its importance lies in the fact that the radial nerve is close to the bone throughout the length of the groove. Mid-shaft fractures of the humerus may damage the radial nerve leading to paralysis or weakness of all extensor muscles distal to the injury. See later: wrist drop (

section 12.8, p. 190).

Muscles of the shoulder region

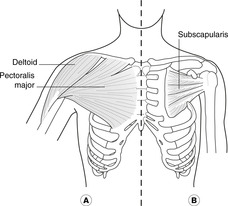

• Pectoralis major (

Fig. 12.11). Attachments: medial half of clavicle (the clavicular head) and sternum, ribs and external oblique aponeurosis (the sternocostal head)–lateral lip of the bicipital groove of the humerus. The two heads can work separately. To demonstrate this, put your hand in front of your chest underneath a desk surface and pull up, feeling the muscle. Now put your hand on top of the desk and push down. Despite its size, we could live well enough without it. It flexes the shoulder (bringing the humerus in front of the chest) and adducts it (although gravity more often than not does this). It is large in creatures that swing from tree to tree and some athletes.

– Nerve supply: medial and lateral pectoral nerves.

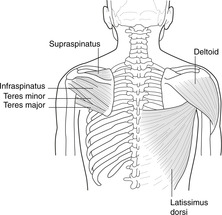

• Latissimus dorsi and teres major (

Fig. 12.12). Latissimus dorsi attachments: lumbosacral fascia, spines of vertebrae L5 up to T7–floor of the bicipital groove of the humerus. It has an extensive trunk attachment but a small humeral attachment. It is the posterior counterpart of pectoralis major, and extends and adducts the shoulder. As it sweeps past the inferior angle of the scapula it is joined by some fibres attached to that bone. It is very closely associated with teres major muscle.

Teres major attachments: lower lateral part of the scapula–medial edge of the bicipital groove of the humerus.

– Nerve supply of both muscles: branches of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus (as befits extensors), the nerve to latissimus dorsi being the thoracodorsal nerve.

•

Deltoid (Figs 12.11,

12.12). Attachments: lateral end of spine of the scapula, acromion, acromioclavicular joint, lateral clavicle–deltoid tuberosity of the humerus.

– Nerve supply; axillary nerve C5, 6. This muscle is often the site of intramuscular injections. If you insert the needle within 4 cm of the acromion you are unlikely to damage the axillary nerve as it enters the muscle from behind the surgical neck of the humerus. If you go lower than this, you deserve to be prosecuted for incompetence.

• Rotator cuff muscles (

Figs 12.12,

12.13). The four muscles of the rotator cuff form a protective sheath for the shoulder joint behind, on top and in front. They are, from back to front:

– Teres minor: lateral aspect of scapula (above teres major)–posterior surface of greater tuberosity of humerus. It is really a slightly detached part of the infraspinatus. Nerve supply: axillary nerve (C5, 6).

– Infraspinatus: infraspinous fossa of the scapula–greater tuberosity of humerus. Nerve supply: suprascapular nerve (C5, 6).

– Supraspinatus: supraspinous fossa of the scapula–upper part of greater tuberosity of humerus. Nerve supply: suprascapular nerve (C5, 6).

– Subscapularis: anterior (costal) surface of scapula (subscapular fossa)–lesser tuberosity of humerus. Nerve supply: subscapular nerves from posterior cord of brachial plexus.

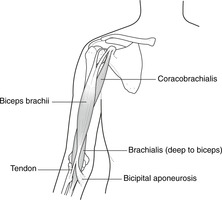

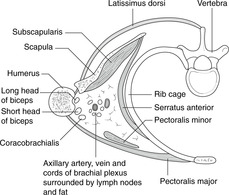

• Biceps and coracobrachialis (

Fig. 12.14). Biceps has two heads: the long head is attached to the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula; the short head is attached to the coracoid process. The tendon of the long head originates within the shoulder joint capsule and passes between the capsule and the synovium to emerge at the bicipital groove of the humerus through which it runs. The two bellies of biceps unite inferiorly to attach to the radius and to the fascia over forearm flexor muscles. Biceps crosses two joints, shoulder and elbow, flexing them both. It is also considered in relation to the elbow joint (see

section 12.5, p. 176).

• Coracobrachialis (unimportant): coracoid process of the scapula–upper humerus.

Both muscles contribute to shoulder flexion.

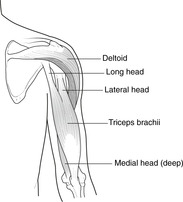

• Triceps (

Fig. 12.15). Attachments: scapula and humerus–ulna. Triceps has three heads:

– long, from the infraglenoid tubercle of the scapula

– lateral, from the back of the humerus, above and lateral to the radial groove (more superficial than lateral)

– medial, from the back of the humerus, below and medial to the radial groove (more deep than medial).

The radial nerve runs through the muscle in the spiral groove of the humerus between the lateral and medial heads.

– Nerve supply: radial nerve (C7, 8).

Movements and stability of the shoulder

The articular surfaces of the shoulder are not a good fit. This means that although the range of movement is very extensive, the joint is unstable and liable to disarticulation with the head of the humerus dislocating, usually anteroinferiorly. Compensating to some extent for the lack of bony stability are the rotator cuff muscles and the glenohumeral ligaments.

Abduction

Deltoid is the main abductor. Supraspinatus is said to initiate the movement by holding the head of the humerus on the scapula so that the deltoid can get some purchase on the movement, but electromyography studies show that both muscles act throughout. When the arm is abducted to about 90°, the greater tuberosity of the humerus comes in contact with the acromion and there is some lateral rotation of the humerus so that more movement is possible.

The accepted wisdom handed down from text to text is that after 90° of abduction the scapula rotates as a result of the action of serratus anterior and trapezius (see above), which allows the arm to be abducted much further. This is wrong, as you will see if you use your eyes: the scapula begins to rotate well before even 45° abduction is reached. Inability to abduct beyond 90°, such as might result from weakness of trapezius and serratus anterior is a nuisance: it would mean that you could not groom your hair, scratch your head, reach for high shelves, and so on.

Nerve supply of abduction

• deltoid and supraspinatus: axillary, suprascapular nerves (both C5, 6)

• scapular rotation: long thoracic nerve (C5, 6, 7); accessory (eleventh cranial) nerve.

Flexion, extension

See above – pectoralis major, biceps, coracobrachialis, latissimus dorsi.

Rotation

• Lateral rotation: mainly by infraspinatus, teres minor and posterior fibres of deltoid.

• Medial rotation: mainly by pectoralis major, subscapularis and teres major.

Shoulder joint capsule, glenohumeral ligaments, dislocations (Fig. 12.13)

Blood supply of the shoulder joint

The blood supply of any joint is profuse. It is necessary to know only that branches of the anterior and posterior circumflex humerals, axillary and brachial arteries supply the shoulder.

Nerve supply of the shoulder joint

As usual (Hilton’s law), sensory fibres from the joint are carried in nerves which supply muscles acting on the joint, particularly the axillary nerve C5, 6.

Synovial cavity and bursas (Fig. 12.13)

The synovial cavity extends inferiorly for some distance, presumably to allow for hyperabduction.

• Subacromial or subdeltoid bursa. This lies between supraspinatus tendon (below) and the acromioclavicular articulation and the attachment of deltoid (above). It has two names because in adduction the bursa is more lateral (subdeltoid), but in abduction it is more medial (subacromial). It is separate from the joint cavity unless supraspinatus tendon is torn.

• Other bursas. There is usually a bursa, an extension of the joint space, deep to subscapularis muscle. Other bursas may also be found.

Nerve injuries

• Axillary nerve: this may be damaged by fractures of the surgical neck of the humerus, or by shoulder dislocations.

• Radial nerve: this may be damaged in the spiral groove by midshaft humeral fractures.

Other conditions

Inflammation of the attachment of supraspinatus to the greater tuberosity is one cause of ‘frozen shoulder’, rotator cuff syndromes, or impingement syndromes (all meaning much the same). It can be very painful and disabling, substantially limiting movement.

Surface anatomy

Normally the most lateral bony point of the skeleton is the greater tuberosity of the humerus. In shoulder dislocations, the head of the humerus is displaced down and medially, and the most lateral point is then the acromion process.

12.4. Axilla

The axilla is bounded by the anterior and posterior axillary folds, the humerus and the rib cage. It contains axillary vessels, components of the brachial plexus, and lymph nodes so often involved in breast disease.

You should:

• describe the boundaries and contents of the axilla

• list the main groups of axillary lymph nodes and the areas and organs, particularly the breast, that drain to them.

Spatial considerations (Fig. 12.16)

The axilla is like a distorted four-sided pyramid:

• base: skin of the armpit

• anterior wall: anterior axillary fold made up of pectoralis major muscle

• medial wall: chest wall with the long thoracic nerve (to serratus anterior) and the lateral thoracic artery passing down

• posterior wall: posterior axillary fold made up of latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles

• lateral ‘wall’: the anterior and posterior walls converge on the bicipital groove of the humerus that contains the tendon of the long head of biceps.

Contents

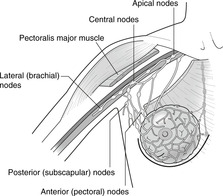

• Lymph nodes (

Fig. 12.17):

– anterior or pectoral group: lymph from most of the breast

– posterior or subscapular group: lymph from the upper trunk and axillary tail of the breast

– lateral group: lymph from the ulnar side of the upper limb

– central group: lymph from all the above groups

– apical group: lymph from the central group (i.e. all the above) and the deltopectoral (infraclavicular) nodes (lymph from radial side of upper limb, alongside the cephalic vein).

From the apical group, which gathers all together, lymph passes to the origin of the brachiocephalic veins where it enters the venous system.

• Fascia. The clavipectoral fascia extends from the clavicle down in the floor of the deltopectoral groove (triangle) and splits to enclose pectoralis minor muscle. Below this, it continues as the suspensory ligament of the axilla that attaches to the axillary skin. None of these details is important.

Long thoracic nerve (of Bell)

It is important in axillary surgery (e.g. for breast cancer) not to damage the long thoracic nerve. This would result in winging of the scapula, impaired shoulder abduction and loss of function. The nerve may also be damaged in those poor unfortunates who fall asleep, for whatever reason, with their arms over the back of a chair.

Lymph from the upper limb

Breast surgery in which the lymphatic channels from the upper limb are occluded will result in lymphoedema (lymphatic engorgement) of the upper limb. This is fortunately less common now with improved pharmacological treatments available.

12.5. Arm, elbow, cubital fossa, supination, pronation

At the elbow, the radiohumeral articulation permits flexion and extension, and the superior radioulnar joint permits pronation and supination. The cubital fossa anterior to the elbow contains the termination of the brachial artery and the median nerve, and is covered by the bicipital aponeurosis. The ulnar nerve passes posterior to the medial epicondyle. Elbow flexion is supplied by C5, 6; extension by C7, 8; pronation and supination by C5, 6.

You should:

• describe the surface anatomy of the elbow region and the cubital fossa

• explain the mechanism of pronation and supination

• describe the innervation of the principal muscles acting at the elbow and superior radioulnar joints.

Bones, joints and ligaments

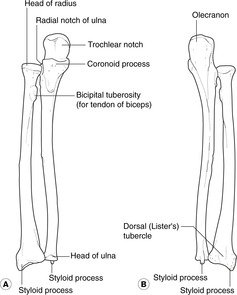

• Olecranon process: triceps attachment.

• Coronoid process: brachialis is attached to its anterior aspect.

• Between the olecranon and coronoid processes is the articular surface for the humerus at which flexion and extension take place.

• Articular surface for radius.

Ulna or ulnar?

Ulna is the name of the bone; ulnar is an adjective that describes other things, as in the ulnar side of the hand.

• Head. This articulates with:

– the capitulum of the humerus, as part of the elbow flexion-extension mechanism; and

– the ulna, as part of the pronation-supination mechanism (see below).

• Neck: immediately distal to the head; the deep branch of the radial nerve (posterior interosseous nerve) is vulnerable here. Damage to it (e.g. radial neck fractures, radial head dislocations) would impair function of the wrist and digital extension.

• Bicipital tuberosity. The tendon of biceps attaches here.

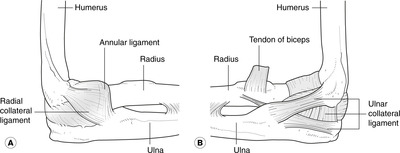

Annular ligament: pronation and supination (Fig. 12.19)

The head of the radius is held against the ulna by the annular ligament attached to the upper and lower margins of the ulnar facet for the superior radioulnar joint. During pronation and supination the head of the radius rotates within this (see below).

Functionally, there are two joints although only one synovial cavity:

• Humerus–ulna: synovial hinge joint for flexion and extension.

• Superior (proximal) radioulnar joint: for pronation and supination. See above.

Injuries

• The ulna can be dislocated posteriorly.

• The head of the radius may be pulled distally, with or without damaging the annular ligament. This is more common in children since the head of the radius is still cartilaginous and the annular ligament is not such a tight fit as in the adult. The deep branch of the radial nerve may be damaged.

Surface anatomy of the elbow region

• The head of the radius is also palpable about 2 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle. You can confirm that it is the head of the radius by feeling it rotate during pronation and supination.

• The brachial artery is a continuation of the axillary at the lower border of teres major. It descends in the flexor compartment of the arm. Soon after its origin it gives off:

• The profunda brachii artery, or deep branch (it usually retains its Latin title), which passes laterally with the radial nerve into the spiral groove.