Chronic prostatitis, although often asymptomatic, may produce a persistent urethral discharge that’s thin, milky, or clear and sometimes sticky. The discharge appears at the meatus after a long interval between voidings, as in the morning. Associated effects include a dull aching in the prostate or rectum, sexual dysfunction such as ejaculatory pain, and urinary disturbances such as frequency, urgency, and dysuria.

Special Considerations

To relieve prostatitis symptoms, suggest that the patient take hot sitz baths several times daily, increase his fluid intake, void frequently, and avoid caffeine, tea, and alcohol. Monitor him for urine retention.

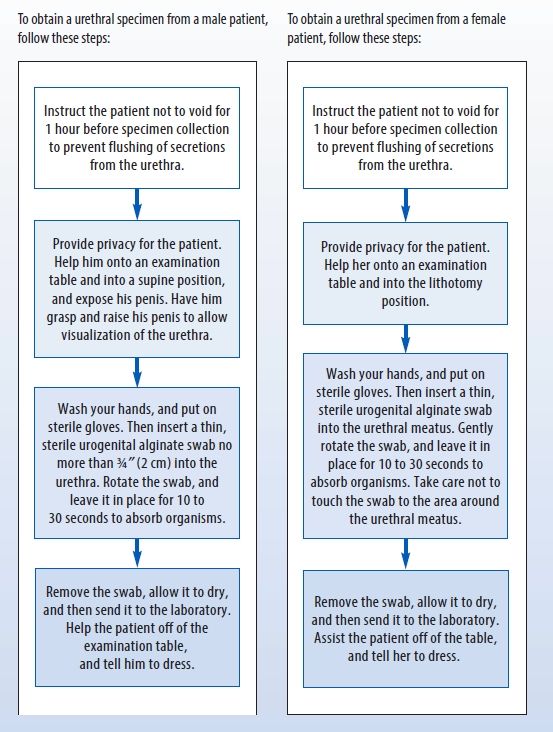

Collecting a Urethral Discharge Specimen

Performing the Three-Glass Urine Test

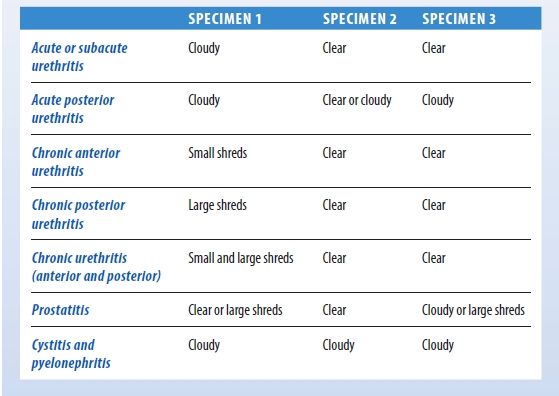

If your male patient complains of urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, flank or lower back pain, or other signs or symptoms of urethritis, and if his urine specimen is cloudy, perform the three-glass urine test.

First, ask him to void into three conical glasses labeled with numbers 1, 2, and 3. First-voided urine goes into glass #1, midstream urine into glass #2, and the remainder into glass #3. Tell the patient to avoid interrupting the stream of urine when shifting glasses, if possible.

Next, observe each glass for pus and mucus shreds. Also, note urine color and odor. Glass #1 will contain matter from the anterior urethra; glass #2, matter from the bladder; and glass #3, sediment from the prostate and seminal vesicles.

Some common findings are shown here. However, confirming diagnosis requires microscopic examination and a bacteriology report.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient with acute prostatitis about the importance of avoiding sexual activity until acute symptoms subside. Conversely, explain to the patient with chronic prostatitis that symptoms may be relieved by engaging in regular sexual activity.

Pediatric Pointers

Carefully evaluate a child with urethral discharge for evidence of sexual and physical abuse.

Geriatric Pointers

Urethral discharge in elderly males isn’t usually related to a sexually transmitted disease.

Reference

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Urinary Frequency

Urinary frequency refers to increased incidence of the urge to void without an increase in the total volume of urine produced. Usually resulting from decreased bladder capacity, frequency is a cardinal sign of urinary tract infection. However, it can also stem from another urologic disorder, neurologic dysfunction, or pressure on the bladder from a nearby tumor or from organ enlargement (as with pregnancy).

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient how many times a day he voids. How does this compare to his previous pattern of voiding? Ask about the onset and duration of the abnormal frequency and about any associated urinary signs or symptoms, such as dysuria, urgency, incontinence, hematuria, discharge, or lower abdominal pain with urination.

Ask also about neurologic symptoms, such as muscle weakness, numbness, or tingling. Explore his medical history for urinary tract infection, other urologic problems or recent urologic procedures, and neurologic disorders. With a male patient, ask about a history of prostatic enlargement. If the patient is a female of childbearing age, ask whether she is or could be pregnant.

Obtain a clean-catch midstream sample for urinalysis and culture and sensitivity tests. Then, palpate the patient’s suprapubic area, abdomen, and flanks, noting any tenderness. Examine his urethral meatus for redness, discharge, or swelling. In a male patient, the physician may palpate the prostate gland.

If the patient’s medical history reveals symptoms or a history of neurologic disorders, perform a neurologic examination.

Medical Causes

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostatic enlargement causes urinary frequency, along with nocturia and possibly incontinence and hematuria. Initial effects are those of prostatism: reduced caliber and force of the urine stream, urinary hesitancy and tenesmus, inability to stop the urine stream, a feeling of incomplete voiding, and occasionally urine retention. Assessment reveals bladder distention.

- Bladder calculus. Bladder irritation may lead to urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, terminal hematuria, and suprapubic pain from bladder spasms. The patient may have overflow incontinence if the calculus lodges in the bladder neck. Greatest discomfort usually occurs at the end of micturition if the stone lodges in the bladder neck. This may also cause overflow incontinence and referred pain to the lower back or heel.

- Prostate cancer. In advanced stages of prostate cancer, urinary frequency may occur, along with hesitancy, dribbling, nocturia, dysuria, bladder distention, perineal pain, constipation, and a hard, irregularly shaped prostate.

- Prostatitis. Acute prostatitis commonly produces urinary frequency, along with urgency, dysuria, nocturia, and purulent urethral discharge. Other findings include fever, chills, low back pain, myalgia, arthralgia, and perineal fullness. The prostate may be tense, boggy, tender, and warm. Prostate massage to obtain prostatic fluid is contraindicated. Signs and symptoms of chronic prostatitis are usually the same as those of the acute form, but to a lesser degree. The patient may also experience pain on ejaculation.

- Rectal tumor. The pressure exerted by a rectal tumor on the bladder may cause urinary frequency. Early findings include changed bowel habits, commonly starting with an urgent need to defecate on arising or obstipation alternating with diarrhea, blood or mucus in the stool, and a sense of incomplete evacuation.

- Reiter’s syndrome. In Reiter’s syndrome, urinary frequency occurs with symptoms of acute urethritis 1 to 2 weeks after sexual contact. Other symptoms of this self-limiting syndrome include asymmetrical arthritis of knees, ankles, and metatarsophalangeal joints, unilateral or bilateral conjunctivitis, and small painless ulcers on the mouth, tongue, glans penis, palms, and soles.

- Reproductive tract tumor. A tumor in the female reproductive tract may compress the bladder, causing urinary frequency. Other findings vary but may include abdominal distention, menstrual disturbances, vaginal bleeding, weight loss, pelvic pain, and fatigue.

- Spinal cord lesion. Incomplete cord transection results in urinary frequency, continuous overflow, dribbling, urgency when voluntary control of sphincter function weakens, urinary hesitancy, and bladder distention. Other effects occur below the level of the lesion and include weakness, paralysis, sensory disturbances, hyperreflexia, and impotence.

- Urethral stricture. Bladder decompensation produces urinary frequency, along with urgency and nocturia. Early signs include hesitancy, tenesmus, and reduced caliber and force of the urine stream. Eventually, overflow incontinence may occur. Urinoma and urosepsis may develop.

- Urinary tract infection. Affecting the urethra, the bladder, or the kidneys, this common cause of urinary frequency may also produce urgency, dysuria, hematuria, cloudy urine, and, in males, urethral discharge. The patient may report bladder spasms or a feeling of warmth during urination and a fever. Women may experience suprapubic or pelvic pain. In young adult males, urinary tract infection is usually related to sexual contact.

Other Causes

- Diuretics. These substances, which include caffeine, reduce the body’s total volume of water and salt by increasing urine excretion. Excessive intake of coffee, tea, and other caffeinated beverages leads to urinary frequency.

- Treatments. Radiation therapy may cause bladder inflammation, leading to urinary frequency.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as urinalysis, culture and sensitivity tests, imaging tests, ultrasonography, cystoscopy, cystometry, postvoid residual tests, and a complete neurologic workup. If the patient’s mobility is impaired, keep a bedpan or commode near his bed. Carefully and accurately document the patient’s daily intake and output amounts.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient in the proper way to clean the genital area, and emphasize the importance of safer sex practices. Explain the need for increasing fluid intake and the frequency of voiding. Teach the patient how to perform Kegel exercises.

Pediatric Pointers

Urinary tract infection is a common cause of urinary frequency in children, especially girls. Congenital anomalies that can cause urinary tract infection include a duplicated ureter, congenital bladder diverticulum, and an ectopic ureteral orifice.

Geriatric Pointers

Men older than age 50 are prone to frequent non–sex-related urinary tract infections. In postmenopausal women, decreased estrogen levels cause urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

Schuiling, K. D. (2013). Women’s gynecologic health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Urinary Hesitancy

Hesitancy — difficulty starting a urine stream generally followed by a decrease in the force of the stream — can result from a urinary tract infection, a partial lower urinary tract obstruction, a neuromuscular disorder, or use of certain drugs. Occurring at all ages and in both sexes, it’s most common in older men with prostatic enlargement. It also occurs in women with gravid uterus; tumors in the reproductive system, such as uterine fibroids; or ovarian, uterine, or vaginal cancer. Hesitancy usually arises gradually, commonly going unnoticed until urine retention causes bladder distention and discomfort.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when he first noticed hesitancy and if he’s ever had the problem before. Ask about other urinary problems, especially reduced force or interruption of the urine stream. Ask if he’s ever been treated for a prostate problem or urinary tract infection or obstruction. Obtain a drug history.

Inspect the patient’s urethral meatus for inflammation, discharge, and other abnormalities. Examine the anal sphincter and test sensation in the perineum. Obtain a clean-catch sample for urinalysis and culture. In a male patient, the prostate gland requires palpation. A female patient requires a gynecologic examination.

Medical Causes

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Signs and symptoms of BPH depend on the extent of prostatic enlargement and the lobes affected. Characteristic early findings include urinary hesitancy, reduced caliber and force of urine stream, perineal pain, a feeling of incomplete voiding, inability to stop the urine stream, and, occasionally, urine retention. As obstruction increases, urination becomes more frequent, with nocturia, urinary overflow, incontinence, bladder distention, and possibly hematuria.

- Prostatic cancer. In patients with advanced cancer, urinary hesitancy may occur, accompanied by frequency, dribbling, nocturia, dysuria, bladder distention, perineal pain, and constipation. Digital rectal examination commonly reveals a hard, nodular prostate.

- Spinal cord lesion. A lesion below the micturition center that has destroyed the sacral nerve roots causes urinary hesitancy, tenesmus, and constant dribbling from retention and overflow incontinence. Associated findings are urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, and nocturia.

- Urethral stricture. Partial obstruction of the lower urinary tract secondary to trauma or infection produces urinary hesitancy, tenesmus, and decreased force and caliber of the urine stream. Urinary frequency and urgency, nocturia, and eventually overflow incontinence may develop. Pyuria usually indicates accompanying infection. Increased obstruction may lead to urine extravasation and formation of urinomas.

- Urinary tract infection. Urinary hesitancy may be associated with urinary tract infection. Characteristic urinary changes include frequency, possible hematuria, dysuria, nocturia, and cloudy urine. Associated findings include bladder spasms; costovertebral angle tenderness; suprapubic, low back, pelvic, or flank pain; urethral discharge in males; fever; chills; malaise; nausea; and vomiting.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Anticholinergics and drugs with anticholinergic properties (such as tricyclic antidepressants and some nasal decongestants and cold remedies) may cause urinary hesitancy. Hesitancy may also occur in those recovering from general anesthesia.

Special Considerations

Monitor the patient’s voiding pattern, and frequently palpate for bladder distention. Apply local heat to the perineum or the abdomen to enhance muscle relaxation and aid urination. Prepare the patient for tests, such as cystometrography or cystourethrography.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient how to perform a clean, intermittent self-catheterization, and discuss the importance of increasing fluid intake and voiding frequently.

Pediatric Pointers

The most common cause of urinary obstruction in male infants is posterior strictures. Infants with this problem may have a less forceful urine stream and may also present with fever due to urinary tract infection, failure to thrive, or a palpable bladder.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Schuiling, K. D. (2013). Women’s gynecologic health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Urinary Incontinence

Incontinence, the uncontrollable passage of urine, can result from a bladder abnormality, a neurologic disorder, or an alteration in pelvic muscle strength. A common urologic sign, incontinence may be transient or permanent and may involve large volumes of urine or scant dribbling. It can be classified as stress, overflow, urge, or total incontinence. Stress incontinence refers to intermittent leakage resulting from a sudden physical strain, such as a cough, sneeze, laugh, or quick movement. Overflow incontinence is a dribble resulting from urine retention, which fills the bladder and prevents it from contracting with sufficient force to expel a urine stream. Urge incontinence refers to the inability to suppress a sudden urge to urinate. Total incontinence is continuous leakage resulting from the bladder’s inability to retain urine.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when he first noticed the incontinence and whether it began suddenly or gradually. Have him describe his typical urinary pattern: Does incontinence usually occur during the day or at night? Does he have any urinary control, or is he totally incontinent? If he is occasionally able to control urination, ask him the usual times and amounts voided. Determine his normal fluid intake. Ask about other urinary problems, such as hesitancy, frequency, urgency, nocturia, and decreased force or interruption of the urine stream. Also, ask if he’s ever sought treatment for incontinence or found a way to deal with it himself.

Obtain a medical history, especially noting urinary tract infection, prostate conditions, spinal injury or tumor, stroke, or surgery involving the bladder, prostate, or pelvic floor. Ask a woman how many pregnancies she has had and how many childbirths.

After completing the history, have the patient empty his bladder. Inspect the urethral meatus for obvious inflammation or anatomic defect. Have female patients bear down; note any urine leakage. Gently palpate the abdomen for bladder distention, which signals urine retention. Perform a complete neurologic assessment, noting motor and sensory function and obvious muscle atrophy.

Medical Causes

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Overflow incontinence is common with BPH as a result of urethral obstruction and urine retention. BPH begins with a group of signs and symptoms known as prostatism: reduced caliber and force of urine stream, urinary hesitancy, and a feeling of incomplete voiding. As obstruction increases, urination becomes more frequent, with nocturia, and, possibly, hematuria. Examination reveals bladder distention and an enlarged prostate.

- Bladder cancer. The patient commonly presents with urge incontinence and hematuria; obstruction by a tumor may produce overflow incontinence. The early stages can be asymptomatic. Other urinary signs and symptoms include frequency, dysuria, nocturia, dribbling, and suprapubic pain from bladder spasms after voiding. A mass may be palpable on bimanual examination.

- Diabetic neuropathy. Autonomic neuropathy may cause painless bladder distention with overflow incontinence. Related findings include episodic constipation or diarrhea (which is commonly nocturnal), impotence and retrograde ejaculation, orthostatic hypotension, syncope, and dysphagia.

- Multiple sclerosis (MS). Urinary incontinence, urgency, and frequency are common urologic findings in MS. In most patients, visual problems and sensory impairment occur early. Other findings include constipation, muscle weakness, paralysis, spasticity, hyperreflexia, intention tremor, ataxic gait, dysarthria, impotence, and emotional lability.

- Prostate cancer. Urinary incontinence usually appears only in the advanced stages of this cancer. Urinary frequency and hesitancy, nocturia, dysuria, bladder distention, perineal pain, constipation, and a hard, irregularly shaped, nodular prostate are other common late findings.

- Prostatitis (chronic). Urinary incontinence may occur as a result of urethral obstruction from an enlarged prostate. Other findings include urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, hematuria, bladder distention, persistent urethral discharge, dull perineal pain that may radiate, ejaculatory pain, and decreased libido.

- Spinal cord injury. Complete cord transection above the sacral level causes flaccid paralysis of the bladder. Overflow incontinence follows rapid bladder distention. Other findings include paraplegia, sexual dysfunction, sensory loss, muscle atrophy, anhidrosis, and loss of reflexes distal to the injury.

- Stroke. Urinary incontinence may be transient or permanent. Associated findings reflect the site and extent of the lesion and may include impaired mentation, emotional lability, behavioral changes, altered level of consciousness, and seizures. Headache, vomiting, visual deficits, and decreased visual acuity are possible. Sensorimotor effects include contralateral hemiplegia, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, apraxia, agnosia, aphasia, and unilateral sensory loss.

- Urethral stricture. Eventually, overflow incontinence may occur here. As obstruction increases, urine extravasation may lead to formation of urinomas and urosepsis.

- Urinary tract infection (UTI). Besides incontinence, UTI may produce urinary urgency, dysuria, hematuria, cloudy urine, and, in males, urethral discharge. Bladder spasms or a feeling of warmth during urination may occur.

Other Causes

- Surgery. Urinary incontinence may occur after prostatectomy as a result of urethral sphincter damage.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as cystoscopy, cystometry, and a complete neurologic workup. Obtain a urine specimen.

Begin management of incontinence by implementing a bladder retraining program. (See Correcting Incontinence with Bladder Retraining.)

If the patient’s incontinence has a neurologic basis, monitor him for urine retention, which may require periodic catheterizations. A patient with permanent urinary incontinence may require surgical creation of a urinary diversion.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient how to perform Kegel exercises and proper self-catheterization techniques, if appropriate. Review with the patient the drugs he is taking.

Pediatric Pointers

Causes of incontinence in children include infrequent or incomplete voiding. These may also lead to UTI. Ectopic ureteral orifice is an uncommon congenital anomaly associated with incontinence. A complete diagnostic evaluation usually is necessary to rule out organic disease.

Geriatric Pointers

Diagnosing a UTI in elderly patients can be problematic because many present only with urinary incontinence or changes in mental status, anorexia, or malaise. Also, many elderly patients without UTIs present with dysuria, frequency, urgency, or incontinence.

Correcting Incontinence with Bladder Retraining

The incontinent patient typically feels frustrated, embarrassed, and, sometimes, hopeless. Fortunately, though, his problem may be corrected by bladder retraining — a program that aims to establish a regular voiding pattern. Here are some guidelines for establishing such a program:

- Before you start the program, assess the patient’s intake pattern, voiding pattern, and behavior (for example, restlessness or talkativeness) before each voiding episode.

- Encourage the patient to use the toilet 30 minutes before he’s usually incontinent. If this isn’t successful, readjust the schedule. Once he’s able to stay dry for 2 hours, increase the time between voidings by 30 minutes each day until he achieves a 3- to 4-hour voiding schedule.

- When your patient voids, make sure that the sequence of conditioning stimuli is always the same.

- Make sure that the patient has privacy while voiding — any inhibiting stimuli should be avoided.

- Keep a record of continence and incontinence for 5 days — this may reinforce your patient’s efforts to remain continent.

CLUES TO SUCCESS

Remember that both your positive attitude and your patient’s are crucial to his successful bladder retraining. Here are some additional tips that may help your patient succeed:

- Make sure the patient is close to a bathroom or portable toilet. Leave a light on at night, and ensure there is a clear pathway to the bathroom.

- If your patient needs assistance getting out of his bed or chair, promptly answer his call for help.

- Encourage the patient to wear his accustomed clothing, as an indication that you’re confident he can remain continent. Acceptable alternatives to diapers include condoms for the male patient and incontinence pads, or panties, for the female patient.

- Encourage the patient to drink 2 to 2½ qt (2 to 2.5 L) of fluid each day. Less fluid doesn’t prevent incontinence but does promote bladder infection. Limiting his intake after 5 p.m., however, will help him remain continent during the night.

- Reassure your patient that episodes of incontinence don’t signal a failure of the program. Encourage him to maintain a persistent, tolerant attitude.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree