(1)

Department of Hematology Oncology, Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute, 33608 Ortega Highway, San Juan Capistrano, CA 92675, USA

(2)

Department of Pathology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

(3)

460 South Spring Street #817, Los Angeles, CA 90013, USA

(4)

Department of Pathology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Keywords

ImmunohistochemistrySurgical pathologyTumor of unknown originUndifferentiated tumorsStain selectionIHC stain panelsAlgorithmsIntroduction

Definition

♦

For this discussion, “unknown tumor” encompasses two situations, an undifferentiated tumor (assumed primary – unknown primary cancer (UPC)) that cannot be reliably diagnosed by light microscopy and a metastasis of unknown origin (MUO)

♦

Tumors of unknown primary account for about 3–5% of all cancer patients, which places them in the ten most common malignancies

♦

The goal is to correctly identify the tumor type and/or primary site while minimizing the number of markers (stepwise panels) and/or the testing time; usually the process is a compromise of these two systems

♦

Tumors of unknown primary define a neoplasm that remains undetermined as to site of origin after thorough clinical, laboratory, imaging, and pathology investigation including immunohistochemistry

♦

Molecular gene expression profiling is a promising method for assigning tissue of origin in cancers of undetermined primary site

♦

The ultimate goal is to direct site-specific antitumor therapy whenever possible

♦

Various studies have shown a success rate of 66–90%

Organization

♦

The initial discussion is primarily about an undifferentiated primary tumor with the following sections concerning an MUO. However, there is extensive overlap between investigation of a UPC and an MUO

♦

The chapter is structured as several groups of tables of differential diagnoses:

By IHC screening panel

By morphology

By a positive reaction for a certain marker

By metastatic site

Approach

♦

Information can guide and simplify the testing:

Is the lesion malignant? This is almost always determined by histological assessment

Is the lesion primary or metastatic?

If metastatic, what is the primary site?

Are there helpful morphologic or clinical features?

•

Distinctive morphology (dirty necrosis in colorectal carcinoma or signet-ring cells in gastric, breast, or occasionally colorectal carcinoma)

•

Clinicoradiographic information (age, gender, location, pattern of spread, serology)

♦

The usual approach is that undifferentiated tumors are first screened to identify the type of cancer – carcinoma, lymphoma, melanoma, or sarcoma. The additional “second-tier” testing is performed to identify the specific type or primary site, as clinically required

♦

Differential diagnosis and additional test panels are based on the results of an initial screening panel, tumor primary or metastatic site, and morphology

♦

With appropriate, useful clinicoradiographic information , the process might be more for confirmation than investigation. This can reduce the test panel to a couple of expected positive and pertinent negative (tissue site) markers. For example, adenocarcinoma in the liver with the history of colon cancer and a panel of CK7, CK20, and CA19-9 can usually identify colon cancer (CK7−, CK20+, CA19-9−) and cholangiocarcinoma (CK7+, CK20±, CA19-9+). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is usually CK7−/CK20−, but the addition of a HepPar1 negative result would help rule out HCC

♦

Ideal tumor markers are highly sensitive (positive in all cases of a particular tumor type) and highly specific (negative in all other tumors). However, less sensitive or specific markers are useful in some situations (e.g., with a limited differential diagnosis). For example, GCDFP-15 is expressed in 35–60% of breast metastases (low sensitivity) but is negative in most other tumors (high specificity). Thus, it is effective when positive but less useful when negative. A probabilistic approach is most appropriate (with an awareness of clinical information, tumor site, morphology, and expected percent positive tumors)

♦

Some markers are positive or negative throughout the tumor tissue (e.g., PSA), but many are typically focal (e.g., CK20, chromogranin). Whether a stain is considered positive depends on the marker, the external and internal controls, the tumor staining intensity and distribution, and the differential diagnosis. For example, a benign schwannoma stains strongly and diffusely for S-100, while a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor is weak and focal

♦

Undifferentiated tumor can be a carcinoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, or melanoma. Sarcomas often require IHC confirmation or subtyping

♦

UPC is predominantly adenocarcinoma, most commonly from the lung, pancreas/bile duct, colon/rectum, kidney, breast, stomach, ovary, liver, esophagus, and prostate. Less commonly, poorly differentiated carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, melanoma, lymphoma, and sarcoma (3%) are identified

♦

Testing panels and differential diagnosis can be based on morphology including epithelioid (carcinoma, melanoma), glandular (carcinoma), spindle (sarcoma, carcinoma, melanoma), small round blue cell (lymphoma, carcinoma, sarcoma, melanoma), and undifferentiated patterns

♦

Immunoreactivity must be assessed in the critical tumor cells while avoiding background stromal cells such as fibroblasts and vascular endothelium as well as tumor-infiltrating macrophages, mast cells, lymphocytes, and other inflammatory cells

Notes

♦

The differential diagnosis of primary tumors is discussed in the immunohistochemistry chapter by organ system and tissue type, with further details included in chapters throughout the book

♦

A few benign and low malignant potential tumors are included when the morphology places them in the differential diagnosis

♦

Tumor genetics are listed in italics. In unknown tumors, molecular testing is most useful for confirming a suspected diagnosis of a sarcoma that has a known and consistent abnormality (e.g., synovial sarcoma). Some genetic results have a prognostic significance. The karyotypic complexity of many tumors limits the usefulness of genetic testing for diagnosis

♦

Molecular testing (cDNA microarrays or RT-PCR) of UPC yields accurate results of 61–89% in various studies. Difficulties occur in test strategy (e.g., microarray design), test performance (e.g., RNA contamination), and tissue availability (e.g., formalin fixed, DNA preservation). Presently, the cost of these studies is high

♦

RT-PCR can be performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue (FFPE) (e.g., c-kit and PDGFRA mutations in GIST)

♦

Using FFPE tissue, FISH probes (e.g., EWS, FKHR, SYT, ALK, CHOP, etc.) can confirm an IHC suspected diagnosis

Limitations

♦

Refer to the introduction of the immunohistochemistry chapter for a discussion; errors may occur in fixation, tissue sampling, processing, and interpretation

♦

Positive controls should be evaluated for every marker, preferably external and internal. The proper expected staining pattern (nuclear, cytoplasmic, or membranous) must be present

♦

Tumors of a certain cell lineage can lose expression of a typical marker or aberrantly express a marker not usually seen in that cell type. This potentially confounding situation is minimized by performing a panel of several expected positive and negative markers

♦

Necrosis and crush artifact can cause false-positive results

♦

Only very rare markers are nearly 100% sensitive and specific. Markers are listed as positive when a significant majority of tumors express the antigen. Low but significant expression is indicated with a percentage

The Undifferentiated Tumor

Screening Panel (Table 3.1)

Table 3.1.

Undifferentiated Tumor Screening Panel a (Listed by Decreasing Expression; Rare Positivity in Parentheses)

Pankeratin | EMA | Vimentin | S–100 | CD45 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Carcinoma | Carcinoma | Sarcoma | Melanoma | Lymphomab |

Nonseminomatous germ cell tumors | (Sarcoma) | Lymphoma | Sarcoma | |

Sarcoma (subset) | (Lymphoma) | Germ cell tumors | (Carcinoma) | |

(Adrenocortical tumors) | (Carcinoma) | (Lymphoma) | ||

(Melanoma) |

♦

To determine cell lineage of an undifferentiated tumor, a typical screening panel includes pankeratin, vimentin, S-100, and ±CD45 (if indicated by morphology). This broadly identifies carcinomas, mesenchymal tumors, melanoma, and lymphomas. CD20, CD3, and CD30 may be added upfront if lymphoma figures high in the differential diagnosis list. Germ cell tumors should be considered based on age and tumor site if known

♦

After the result of the screening panel is obtained, often a second testing panel is chosen to further characterize the tumor type or primary site, for example, lymphoma tested for specific subtype or a carcinoma for neuroendocrine, squamous differentiation or markers of a specific organ tissue type

♦

Tumors can stain with more than one screening antibody (e.g., lymphoma for vimentin and CD45); the strength and combination direct the final diagnosis or additional testing. Even if not definitive, often results of initial screening will reinforce a morphologic impression

♦

Rare tumors show no expression with the screening panel:

False negatives: problems with fixation and test processing (check controls)

True biological negatives: undifferentiated tumors might not express any of the antigens tested; such rare tumors are signed out as “malignant neoplasm, not otherwise specified” with a discussion of the IHC results. Additional sampling and/or molecular testing might be helpful in these rare cases

Tumors that are negative with the initial screen include Hodgkin lymphoma (CD45−, CD15+, CD30+, suspected based on morphology), anaplastic large cell lymphoma (CD45-, CD30+, EMA+), and S-100-negative melanoma (4%)

Expression of all markers or multiple conflicting markers could be due to processing problems or aberrant antigen expression

Unknown Primary Cancer

♦

UPC is primarily carcinoma , with a few percentages of melanoma, lymphoma, and sarcoma

♦

The majority (60%) are adenocarcinomas, and 30% are undifferentiated carcinomas (mostly poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas), with 5–10% squamous carcinomas and 5% neuroendocrine carcinomas

♦

In autopsy studies , the most common unknown adenocarcinoma primary sites are the lung, pancreas, bowel, kidney, biliary, stomach, ovary/uterus, and prostate

♦

Morphology can be helpful but by definition is not a defining feature: dirty necrosis (intraglandular cell debris) is typically associated with colorectal primaries, and signet-ring cells are often seen in gastric, breast, and occasionally colorectal primaries

♦

CK7 and CK20 staining pattern is very helpful in separating carcinomas into groups (Table 3.3). In some cases, combined with morphology and patient history, a diagnosis can be rendered. Alternatively, a third-tier test panel can be based on the CK7/CK20 results for a more definitive diagnosis. Again, the characterization is not absolute. CK7/CK20 testing is not diagnostic in gastric adenocarcinoma, which can show any of the four possible staining patterns (Table 3.3)

Table 3.2.

The Stability of CK7 and CK20 Expression in Primary and Metastatic Adenocarcinoma (Modified from Tot 2002 , Tables 2–3, Reported as Primary and Metastasis (%))

CK7 | CK20 | |

|---|---|---|

Lung | 98 and 73 | 9 and 20 |

Pancreatobiliary | 93 and 93 | 50 and 42 |

Colon | 16 and 15 | 91 and 93 |

Kidney | 17 and 0 | 7 and 0 |

Stomach | 55 and 42 | 71 and 48 |

Endometrium | 96 and 92 | 19 and 13 |

Ovary | 88 and 68 | 25 and 8 |

Urothe lium | N/A | 78 and 79 |

Prostate | 11 and 13 | 19 and 25 |

Breast | 90 and 78 | 7 and 8 |

Table 3.3.

Pankeratin- Positive, Vimentin-Negative Tumors

CK7+ and CK20− | CK7+ and CK20+ | CK7− and CK20+ | CK7− and CK20− |

|---|---|---|---|

Lung, nonmucinous adenocarcinoma TTF-1 (nuclear) Napsin A Lung, squamous cell carcinoma (22%) (Fig. 3.1) CK5/CK6 P40 p63 (nuclear) Lung , small cell carcinoma (24%) TTF-1 (nuclear) CD56 Chromogranin Synaptophysin Breast, carcinoma GCDFP-15 Mammaglobin Her2 (membranous) ER/PR (nuclear) Ovary, nonmucinous carcinoma CA125 WT1 (nuclear) ER/PR Pancreatobiliary, adenocarcinoma (28%) CA19-9 CA125 (50%) CDX2 (70%, nuclear) Endocervix, adenocarcinoma mCEA Thymic carcinoma CD5 CK5/CK6 Stomach, adenocarcinoma (19%) CDX2 (nuclear, 73%) Renal clear cell carcinoma (17%) RCC Ma CD10 PAX 8 3p deletion Hepatocellular carcinoma (15%) HepPar1 pCEA (canalicular) CD10 (canalicular) | Urothelium, carcinoma CK5/CK6, k903 p63 (nuclear) Pancreatobiliary, adenocarcinoma (64%) CA19-9 CA125 (50%) CDX2 (70%, nuclear) Ovary, mucinous carcinoma CA125 WT1 (40%, nuclear) Lung, mucinous adenocarcinoma CDX2 (nuclear) Choriocarcinoma βhCG Stomach, adenocarcinoma (32%) CDX2 (nuclear, 73%) | Colorectum, adenocarcinoma CDX2 (nuclear) Villin (membranous) Merkel cell carcinoma CD56 Chromogranin Synaptophysin Stomach, adenocarcinoma (35%) CDX2 (nuclear, 73%) | Hepatocellular carcinoma (78%) HepPar1 pCEA (canalicular) CD10 (canalicular) Renal clear cell carcinoma (80%) RCC Ma CD10 PAX 8 3p deletion Prostate, adenocarcinoma PSA, PAP, AMACR Squamous cell carcinoma (70%) CK5/CK6, k903 p63 (nuclear) Lung, small cell carcinoma (76%) TTF-1 (nuclear) CD56 Chromogranin Synaptophysin Stomach, adenocarcinoma (14%) CDX2 (nuclear, 73%) |

Organ-“Specific” and Other Markers

♦

None are completely specific or sensitive

♦

TTF-1 (nuclear) is useful for identifying metastatic adenocarcinoma as a lung primary, other carcinomas being rarely positive

However, it is not specific for small cell neuroendocrine tumors; up to 50% of small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas from all other primary sites are positive for TTF-1 [lung 83%, all extrapulmonary 42% (GI 53%, GYN 39%, bladder 33%)]

Also positive in thyroid tumors

♦

CDX2 (nuclear) .

Typically expressed in the GI and pancreatobiliary tract (colorectal, stomach, GEJ, pancreatobiliary tract, intestinal carcinoid tumors)

Also positive in mucinous ovary, lung, and urinary bladder adenocarcinoma

♦

GCDFP-15

Typically used to identify breast tumors

Also positive in salivary gland, prostate, and skin adnexal tumors

♦

ER/PR (nuclear)

Typically used to identify breast and endometrial tumors

Also positive in some ovary, lung, and neuroendocrine tumors

Negative in colorectum and HCC

♦

CA125.

Typically used to identify ovarian tumors

Also positive in mesothelioma, pancreatobiliary tract, lung, endocervix, and urinary bladder adenocarcinoma

♦

CA19-9

Typically used to identify pancreatobiliary tract tumors

Also positive in ovary, colorectum, and lung tumors

♦

PSA

Typically used for prostate tumors

Also positive in rare salivary gland and breast tumors

♦

AMACR is useful for identifying prostatic carcinoma but not as much for identifying the prostate as a primary site unless there is strong clinical context

Carcinomas positive for AMACR: 92% colorectum, 83% prostate, 44% breast, 14% lung, 10% melanoma, and 7% endometrium

♦

HepPar1 .

Typically used to identify HCC

Positive in up to 50% of gastric carcinomas

♦

Thyroglobulin : specific to thyroid follicular cell tumors

♦

RCC Ma

Used to identify conventional clear cell and papillary renal cell carcinoma

Also positive in yolk sac tumor, embryonal carcinoma, and mesothelioma

♦

Monoclonal CEA

Positive in the lung, colon, stomach, pancreas, bladder, endocervix, breast, chordoma, and urothelium

Negative in the mesothelium, prostate, kidney, liver, adrenal, and endometrium

Note: polyclonal CEA antibodies typically show much less specificity, but it can be used to demonstrate a canalicular pattern in HCC

♦

EMA

Positive in most carcinomas and some sarcomas (synovial sarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma), also meningioma, choroid plexus tumors, chordoma, and ependymoma

Negative in adrenocortical carcinoma, HCC, seminoma, embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, granulosa cell tumor, and Sertoli cell tumor

♦

WT1

Typically used to identify Wilms tumor

Also positive in mesothelioma, ovarian serous carcinoma, sex cord-stromal tumors, granulosa cell tumor, Sertoli cell tumor, metanephric adenoma, and desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT)

♦

HMB45

Typically used to identify melanoma

Also positive in perivascular epithelial cell tumors (PEComas) such as angiomyolipoma and clear cell sarcoma of soft parts

♦

Melan-A

Typically used to identify melanoma

Also positive in adrenocortical tumors, PEComas, and clear cell sarcoma of soft parts

♦

SOX 10 .

Nuclear marker common in melanomas, including spindle cell

Also in gliomas, schwannomas, some breast cancers, and others

♦

PAX 8 .

Nuclear marker in most renal, ovarian, endometrial, and cervical cancers

Thyroid cancer also positive

Other cancer types are mostly negative

♦

p63 .

Nuclear marker positive in most squamous carcinomas but also up to a third of adenocarcinomas and some lymphomas

♦

P40 .

Nuclear marker positive in most squamous carcinomas, less than 10% of adenocarcinomas, and not in lymphomas (compare with p63) (Fig. 3.1)

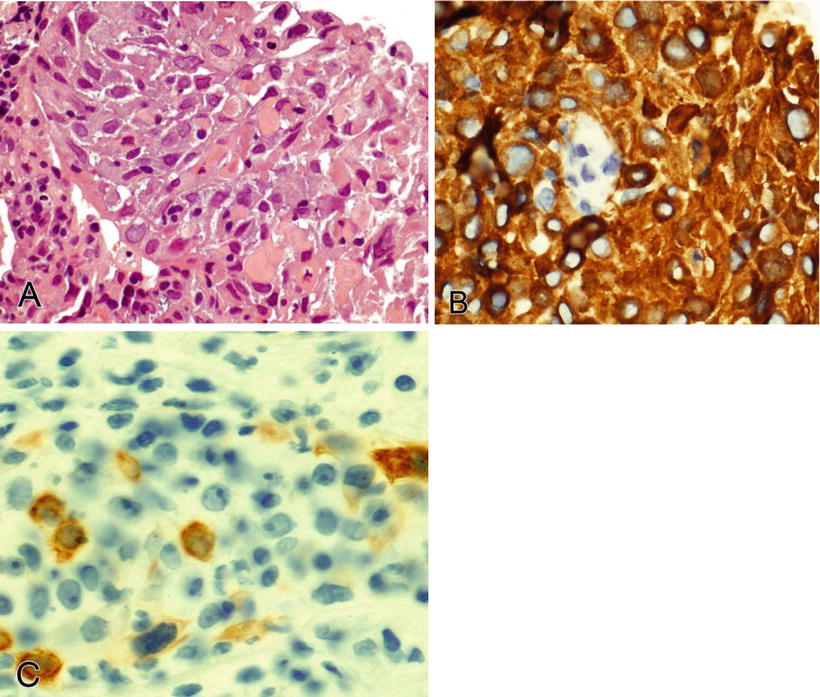

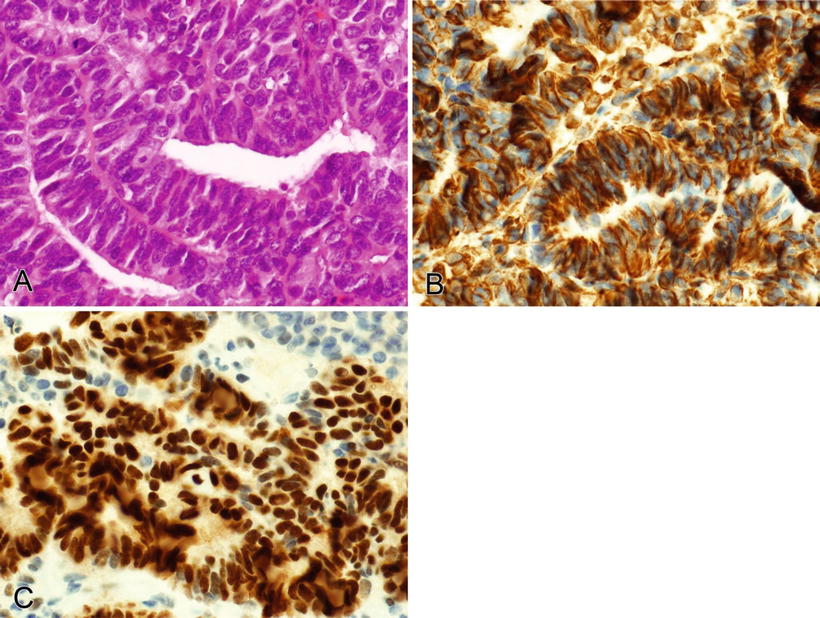

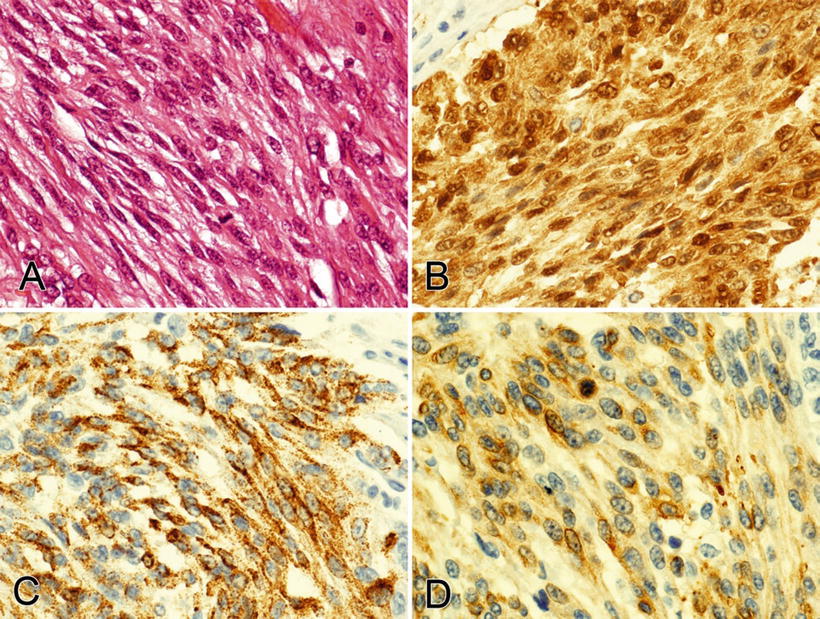

Fig. 3.1.

Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (A) of the lung is diffusely positive for CK5/CK6 (B) and focally positive for CK7 (C).

Pitfalls

♦

EMA: stains plasma cells, L&H cells (nodular lymphocyte predominant HL), and some neoplastic T cells (anaplastic large cell lymphoma)

♦

Pankeratin: stains plasma cells occasionally

♦

CD117: stains mast cells and myeloid precursors

♦

Mucinous tumors show variable staining for tissue-associated markers within primary sites; CK7/CK20/CDX2 can show various patterns in the lung, nasal cavity, ovary, cervix, etc. This could be due to varying degrees of intestinal differentiation

Notes

♦

Based on gender and tumor site, a panel for epithelioid cell tumors (cohesive groups of cells with moderate amounts of cytoplasm) could include HepPar1 for the liver; RCC Ma, PAX8, or CD10 for the kidney; p63 for the bladder; inhibin for the adrenocortex; and CK5/CK6, CK7, and CK20

♦

Benign entrapped cells of the organ tissue (e.g., liver, lung, mesothelium) containing the metastasis must be differentiated from the tumor cells, e.g., benign hepatocytes admixed with cells of metastatic breast carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry must be interpreted in the context of the morphology

♦

Squamous cell carcinoma primary site usually cannot be identified by IHC except for the group of lung tumors that express TTF-1 (up to 25%)

♦

There are no useful positive markers for gastric tumors ; negative results for other markers can be helpful

For example, in the differential diagnosis of primary gastric signet-ring cell carcinoma versus metastatic lobular breast carcinoma, CK20 and CDX2 (nuclear) are positive in the stomach (both negative in the breast), and ER/PR (nuclear) and GCDFP positive in the breast (all negative in the stomach). CK20 and CDX2 are also positive in colorectal carcinoma, and this might be more strongly considered in a different metastatic site

♦

CK7-negative tumors in the lung and ovary are usually metastases

♦

Dennis et al. (2005) identified a ten-marker panel (CK7, CK20, TTF-1, CDX2, CA125, ER, GCDFP-15, lysozyme, mesothelin, and PSA) that correctly classified 88% of UPC. Difficulties were identified when differentiating the stomach and pancreas, stomach and colon, ovary and pancreas, and breast and ovary

♦

Lagendijk et al. (1998) used a six-marker panel (CK7, CK20, CA125, CEA, ER, and GCDFP), which classified 80–90% of tumors

Differential Diagnosis Based On The Screening Panel Result

♦

The differential diagnoses discussed below are based on the results of the screening panel

Pankeratin-Positive, Vimentin-Negative Tumors (Table 3.3)

♦

This staining pattern is presumptive for carcinoma

♦

The subsequent test panel is based on patient history, tumor site, morphology, and extent and strength of keratin staining

♦

If vimentin is not tested, the diagnoses in Table 3.4 (keratin and vimentin positive) should also be considered

Table 3.4.

Pankeratin-Positive and Vimentin- Positive Tumors

Strong keratin | Focal keratin | Rare keratin |

|---|---|---|

Salivary and sweat gland carcinoma CK7+/CK20− GCDFP Endometrioid carcinoma (Fig. 3.2) CK7+/CK20− ER/PR (nuclear) Ovary, serous carcinoma CK7+/CK20− ER/PR (nuclear) WT1 (nuclear) p53 (nuclear) PAX 8 (nuclear) Thyroid, papillary, and anaplastic carcinoma CK7+/CK20− TTF-1 (nuclear) Thyroglobulin PAX 8 (nuclear) Squamous cell carcinoma CK5/CK6 p63 Mesothelioma CK7+/CK20− Calretinin CK5/CK6 D2-40 WT1 (nuclear) Chordoma S-100 EMA Epithelioid sarcoma CD34 INI1 (nuclear, loss of staining) Myoepithelial carcinoma SMA SMMHC Calponin p63 Embryonal carcinoma CK7+/CK20− CD30 PLAP (membranous) OCT4 (nuclear) Yolk sac tumor CK7−/CK20− AFP α1AT PLAP (membranous) Spindle cell carcinoma | Renal clear cell carcinoma CK7−/CK20− (80%) CK7+/CK20− (17%) RCC Ma PAX 8 (nuclear) CD10 3p deletion Adrenocortical neoplasms (Fig. 3.3) Inhibin Melan-A Synaptophysin Synovial sarcoma (Fig. 3.4) bcl-2 CD99 (membranous) S-100 t(X;18) Angiosarcoma (especially epithelioid variant), hemangioendothelioma CD34 CD31 Fli-1 (nuclear) Desmoplastic small round cell tumor Desmin (dot-like) EMA WT1 (nuclear) CD99 (membranous) t(11;22) (p13;q12) Ewing sarcoma CD99 (membranous) Fli-1 (nuclear) t(11;22) (q24;q12) Extrarenal rhabdoid tumor INI1 (nuclear, loss of staining) EMA CD99 (membranous) Synaptophysin MSA Abnormalities 22q11.2 Sarcomatoid carcinoma | Leiomyosarcoma SMA MSA Desmin Calponin Caldesmon Melanoma S-100 SOX 10 HMB45 Melan-A Seminoma CK7+/CK20− (28%) PLAP (membranous) CD117 OCT4 (nuclear) Rhabdomyosarcoma Desmin Myo D1 (nuclear) Myogenin (nuclear) CD99 (membranous, focal) Embryonal: LOH 11p15.5 Alveolar: t(2;13), t(1;13) |

♦

Note that some types of carcinoma are typically or occasionally positive for the mesenchymal marker, vimentin (Table 3.4). These include endometrium (endometrioid), salivary gland, kidney (conventional clear cell), thyroid (papillary and anaplastic), adrenocortex, ovary (endometrioid and serous), and squamous cell carcinoma (Figs. 3.2, 3.3, and 3.4)

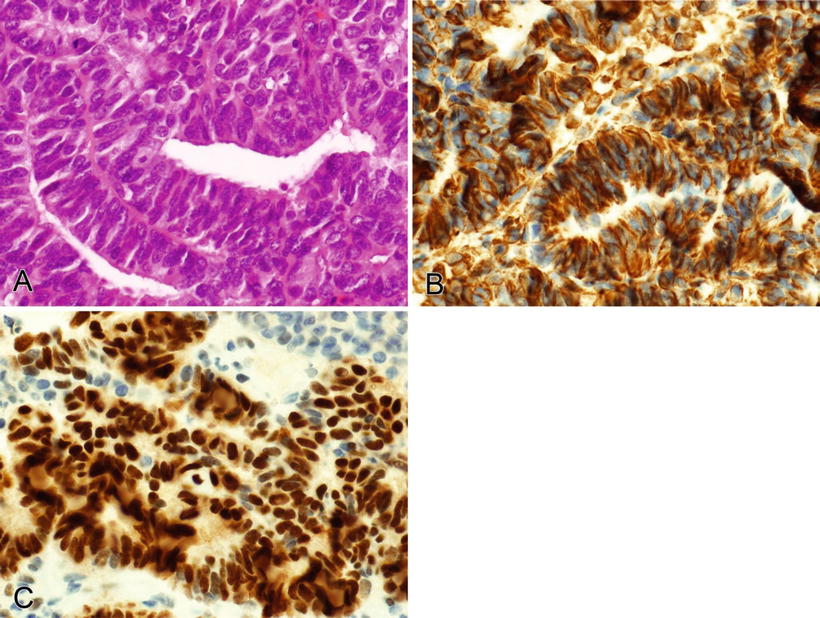

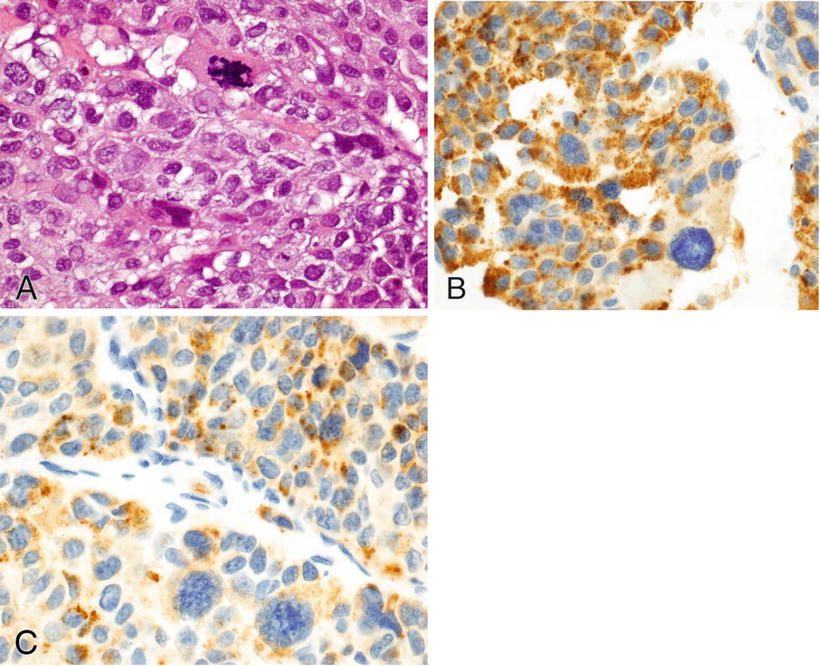

Fig. 3.2.

Endometrioid endometrial carcinoma (A) is positive with vimentin (cytoplasmic) (B) and ER (nuclear) (C).

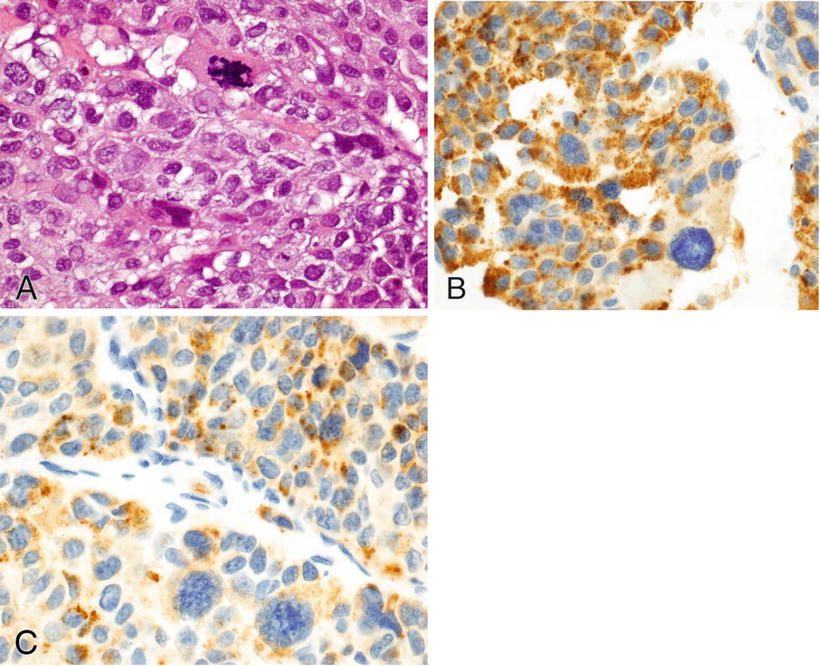

Fig. 3.3.

Adrenocortical carcinoma (A) is positive for inhibin (B) and Melan-A (C).

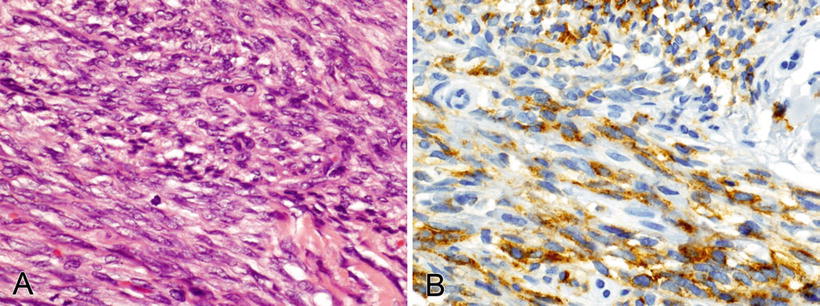

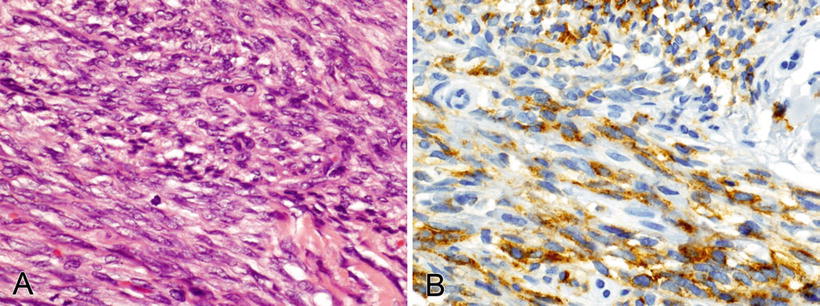

Fig. 3.4.

Synovial sarcoma (A) focally positive for pankeratin (B).

Pankeratin- and Vimentin-Positive Tumors (Table 3.4)

♦

The subsequent test panel is based on patient history, tumor site, morphology, and extent and strength of keratin staining

♦

This staining pattern is seen in some types of sarcoma and in the vimentin-positive subset of carcinoma

Vimentin-Positive, Pankeratin-Negative Tumors (Table 3.5)

Table 3.5.

Vimentin-Positive, Pankeratin-Negative Tumors

S–100 | SMA, MSA | Miscellaneous |

|---|---|---|

Melanoma HMB45 (Fig. 3.5) Melan-A Tyrosinase Mitf (nuclear) SOX 10 (nuclear) Langerhans cell histiocytosis CD1a Langerin Clear cell sarcoma (soft tissue) HMB45 Melan-A t(12;22) Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (Focal) Granular cell tumor Inhibin Adipose tumors Cartilage tumors | Angiomyolipoma HMB45 Fibromatosis β-Catenin Gastrointestinal stromal tumor CD117 CD34 DOG-1 SMA (25%) C–kit, PDGFRA abnormalities Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor ALK 2p23 rearrangements Myofibroblastoma CD34 Desmin ER/PR (nuclear) Leiomyosarcoma Desmin Caldesmon Glomus tumor CD34 Rhabdomyosarcoma Desmin Myo D1 (nuclear) Myogenin (nuclear) CD99 (membranous, focal) Embryonal: LOH 11p15.5 Alveolar: t(2;13), t(1;13) | Seminoma PLAP (membranous) CD117 OCT4 (nuclear) Angiosarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma CD31 CD34 Fli-1 (nuclear) Pankeratin (focal, weak) Kaposi sarcoma CD31 CD34 Fli-1 (nuclear) HHV8 (nuclear) Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma CD99 (membranous) S-100 (cartilage) Alveolar soft parts sarcoma TFE3 (nuclear) t(X;17) Osteosarcoma |

♦

These tumors are primarily sarcomas but also include melanoma, with various morphologic expressions, including spindled, epithelioid, and pleomorphic (Fig. 3.5)

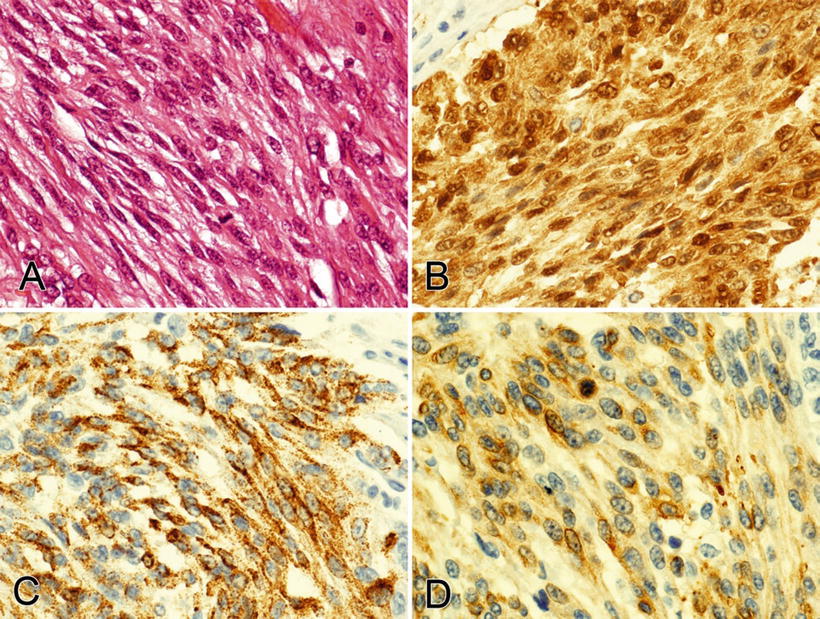

Fig. 3.5.

This spindle cell melanoma (A) is positive for S-100 (B), HMB45 (C), and Melan-A (D); most desmoplastic and spindle cell melanomas are negative for HMB45 (0–19% positive) and Melan-A (0–15% positive).

♦

This table includes those tumors that are typically pankeratin negative (see Table 3.3 for the rarely positive tumors)

♦

The subsequent testing panel is based on patient history, tumor site, and morphology

CD45-Positive and CD45-Negative Hematolymphoid Neoplasms (Table 3.6)

Table 3.6.

Hematolymphoid Tumors with Negative or Frequently Absent CD45 Expression

Blastic or small round blue cell | Plasmacytic (CD20 negative) | Pleomorphic large cell | Spindle cell |

|---|---|---|---|

Lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (Fig. 3.6) B cell CD19, 22, 79a, 99 PAX-5 (nuclear) CD10 TdT (nuclear) CD5, 23, 43 co-expressed T cell CD3, 1a, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 99 TdT (nuclear) Myeloid sarcoma (subtype dependent) CD34 MPO CD13, 33, 99 HLA-DR | Plasmacytoma, multiple myeloma CD38 CD138 CD79a Ig gene rearrangement Plasmablastic lymphoma CD38 CD138 CD79a EBER (EBV) Ig gene rearrangement | Classical Hodgkin lymphoma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|