Chapter 31 Tumors of the hair follicle

Hair follicle nevus

Clinical features

Hair follicle nevus (congenital vellus hamartoma) is an extremely rare hamartomatous lesion, which is usually evident at birth or develops in childhood as a small (less than 1 cm diameter) solitary papule on the face, the preauricular area, and the ear.1–13 Occasional cases presenting in adults have also been described.2,6 Rarely, hair follicle nevi are multiple and may then be arranged in a linear distribution following the lines of Blaschko or they can be associated with epidermal nevus-like lesions.14,15 An association with ipsilateral alopecia, leptomeningeal angiomatosis and frontonasal dysplasia has been documented.11,16

Histological features

Histologically, hair follicle nevus is characterized by proliferation of mature vellus hair follicles, some of which are associated with small sebaceous glands. The follicles appear to be at the same stage of differentiation and are located abnormally high within the dermis. The perifollicular fibrous sheath is thickened and the follicles are embedded in fibrous tissue. Smooth as well as striated muscle may rarely be present and the lesion is occasionally associated with a calcified nodule.8,10

Woolly hair nevus

Clinical features

Woolly hair nevus is an exceedingly rare, nonhereditary condition characterized clinically by a well-defined area of tightly curled hair on the scalp (Fig. 31.1).1–16 The hair is frequently thinner and lighter in color compared to the surrounding normal hair and combing is difficult. There is no gender predilection.

Three distinct groups of patients are identified:

The term ‘acquired progressive kinking of hair’ has, however, been applied to a number of presentations. Most commonly, it refers to progressive kinking of hair in androgen-dependent locations with the subsequent development of androgenic alopecia.18,23–25

Woolly hair nevus has also been associated with systemized linear epidermal nevus, precocious puberty, incontinentia pigmenti, and ocular abnormalities such as persistent papillary membrane.1,4,8,14,27

Comedo nevus

Clinical features

Comedo nevus (comedone nevus, nevus comedonicus) represents an uncommon abnormality of pilosebaceous development and presents as an usually asymptomatic group of comedones, which may be localized or arranged in a linear, sometimes zosteriform, pattern, frequently following the lines of Blaschko.1–3 The lesions are typically unilateral but rare cases with bilateral involvement have been reported.4–6 The face, neck or upper trunk is most commonly affected (Figs 31.2, 31.3).1,2 Rarely involved regions include the genital area in addition to the palm and wrist.7–9 Very occasionally, the condition is much more extensive and widely distributed about the body.1,10–12 Lesions are usually present at birth or develop within the first two decades of life.13 There is an equal sex incidence.2,14 The nevus sometimes shows inflammatory changes and sinuses; fistulae and severe scarring may be evident.2,12,15

Fig. 31.2 Comedone nevus: there is a linear band of comedones.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Fig. 31.3 Comedone nevus: close-up view.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Clinically, plugged sweat pores in a linear distribution may mimic comedones. Nevus comedonicus is sometimes associated with other cutaneous disorders such as ichthyosis, trichilemmal cysts, accessory breast tissue, hidradenoma papilliferum, and syringocystadenoma papilliferum in addition to follicular tumors including trichofolliculoma, dilated pore of Winer, and pilar sheath acanthoma as well as basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma.16–22 An occasional association with systemic manifestations (nevus comedonicus syndrome) has been documented, including scoliosis, fused vertebrae or hemivertebrae, spina bifida occulta, finger deformity, clinodactyly, polydactyly and syndactyly of fingers and toes, rudimentary toe, cataracts, microcephaly, seizures, EEG abnormalities, and transverse myelitis.11,20,23–30

Pathogenesis and histological features

A mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene identical to that documented in Apert’s syndrome has been identified in a nevus comedonicus but not in unaffected skin from the same patient.31 This finding suggests that nevus comedonicus syndrome may potentially represent a mosaic presentation of Apert’s syndrome, which shares at least some of the skeletal manifestations observed in patients with nevus comedonicus syndrome.31

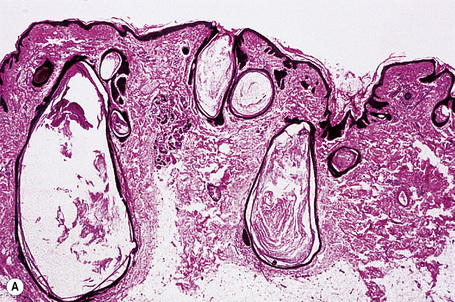

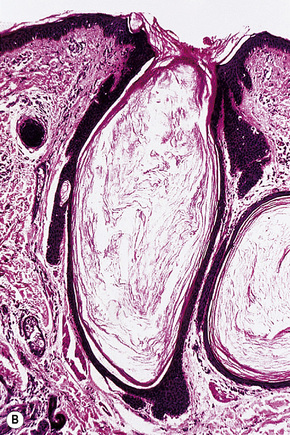

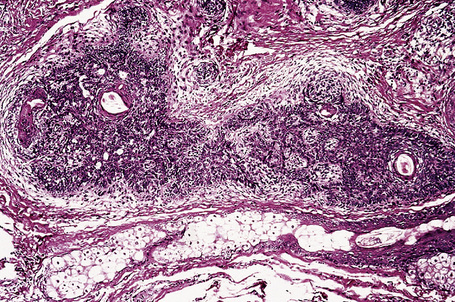

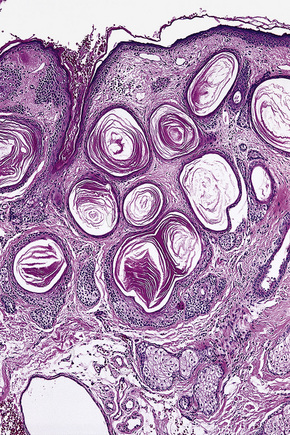

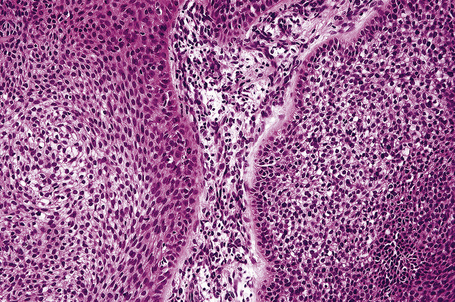

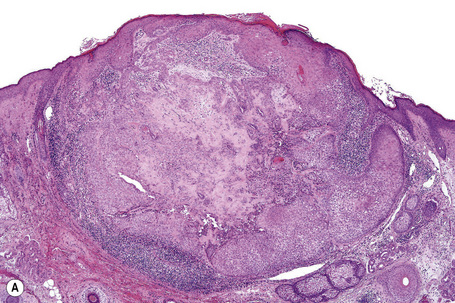

The epidermis is hyperkeratotic and variably acanthotic or atrophic. Occasionally, it shows irregular proliferation into the adjacent dermis.2 Arising from it are large numbers of atrophic cystically dilated hair follicles containing abundant keratinous debris (Fig. 31.4). Sebaceous glands are usually normal, but sometimes they are diminished in number or size.1,2,10 Infection or leakage of cyst contents can result in a focal acute or granulomatous inflammatory response. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis may be an additional feature and the presence of follicular cysts resembling dilated pores of Winer has been described.32–37

Basaloid follicular hamartoma

Clinical features

Basaloid follicular hamartoma is a rare condition with varied clinical expression.1 Solitary, localized, linear nevoid, generalized, and inherited variants are recognized.2–4

Fig. 31.5 Basaloid follicular hamartoma: note the pale infiltrated plaques involving the upper lip.

By courtesy of the late N.P. Smith, MD, Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Pathogenesis and histological features

Molecular studies have demonstrated the importance of the sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathway in the development of basal cell carcinoma. Recent data have implicated alterations in this pathway in the molecular pathogenesis of basaloid follicular hamartoma.29

Fig. 31.8 Basaloid follicular hamartoma: note the peripheral nuclear palisading.

By courtesy of the late N.P. Smith, MD, Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

By immunohistochemistry, basaloid follicular hamartoma shows scarce expression of bcl-2 and Ki-67.13,32 The surrounding stroma contains conspicuous CD34+ cells.32

Differential diagnosis

Basaloid follicular hamartoma can be distinguished from basal cell carcinoma by the absence of a retraction artifact separating the tumor strands from the adjacent dermis, inconspicuous mitotic activity, and apoptosis. Immunohistochemically, basal cell carcinoma shows strong expression of bcl-2 and marked proliferative activity with MIB-1.13,33,34 A CD34+ spindle cell population does not surround the tumor nodules or strands of basal cell carcinoma.13

Dilated pore

Clinical features

Dilated pore (Winer) is a common, usually solitary, lesion which presents as a large comedone on the face or neck, typically in an adult.1 There is a slight male predilection (2:1).2 Development of basal cell carcinoma within a dilated pore has rarely been reported.3

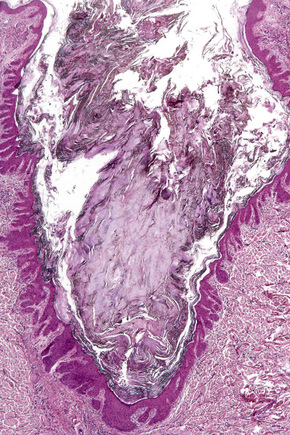

Histological features

The dilated pore consists of a keratin-plugged, cystically dilated hair follicle, which is usually superficially located, although occasionally it extends into the subcutaneous fat (Fig. 31.10).2,4,5 It is lined by stratified squamous epithelium, which is typically acanthotic, particularly in the deeper aspect of the comedone. Characteristically, the epithelium proliferates as irregular strands into the adjacent dermis (Fig. 31.11). Vellus hairs and sebaceous glands are sometimes present within the cyst wall.

Pilar sheath acanthoma

Clinical features

Pilar sheath acanthoma, which is usually located on the upper lip, consists of a solitary asymptomatic, small (0.5–1 cm) skin-colored nodule with a central pore containing keratinous debris.1–5 It occurs equally in men and women.

Histological features

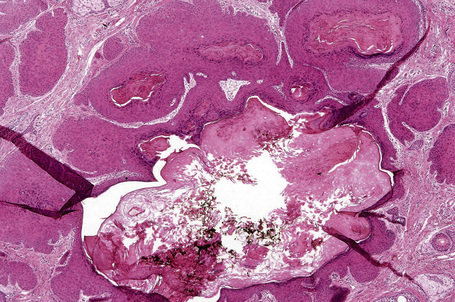

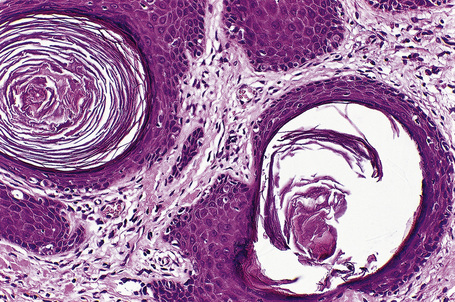

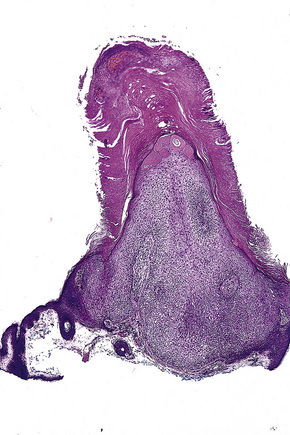

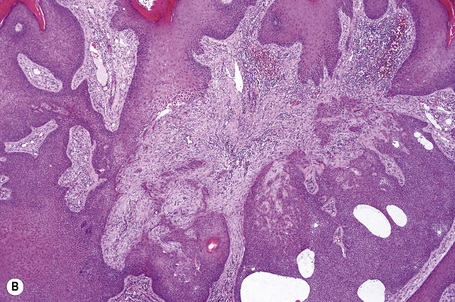

Arising from the epidermis is a multilobulated cystic invagination from which numerous tumor lobules extend into the surrounding dermis and sometimes involve the subcutaneous fat or skeletal muscle (Fig. 31.12).1 The cyst wall is composed of keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium with a granular cell layer. The lobules are of pilar epithelium which, due to the presence of glycogen, may be vacuolated (Fig. 31.13).2,3 Peripheral palisading of nuclei can be a feature, and occasionally a diastase-resistant, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive hyaline sheath encircles the lobules (Fig. 31.14). Keratinization is usually infundibular and accompanied by keratin cyst formation. Occasionally, however, the latter shows a trichilemmal epithelial lining.3 A tumor stroma is usually inconspicuous.

Follicular infundibulum tumor (infundibuloma)

Clinical features

Follicular infundibulum tumor is a rare lesion that occurs most frequently on the head and neck. It presents as an asymptomatic, solitary, scaly nodule up to 1.5 cm in diameter often misdiagnosed clinically as basal cell carcinoma.1–7 It is more common in females and affects the middle aged and elderly.5 Rarely, it presents with multiple lesions and an eruptive variant has been documented.8–13 Tumor of follicular infundibulum may arise within an organoid nevus and occasionally it is associated with Cowden’s disease.7,10,14

Histological features

The lesion is characterized by a fenestrated epithelial plate connected to the epidermis at multiple points and showing a point of attachment to the follicular external root sheath of adjacent vellus hairs (Fig. 31.15).2,5 The tumor cells are pale staining due to glycogen and show peripheral palisading (Fig. 31.16).2 An eosinophilic basement membrane is usually evident.2 A characteristic feature is marked condensation of elastic fibers outlining the base of the lesion.2 Eccrine and sebaceous differentiation have rarely been reported and one example has been described in association with a trichilemmal tumor.15–17

Trichoadenoma

Clinical features

Trichoadenoma is a rare tumor that most commonly presents on the face and to a lesser extent the buttocks of adults, occurring equally in men and in women.1–7 Very occasionally the neck, upper arm, and thigh may be affected. Congenital and childhood presentation is unusual.4,8,9 The solitary asymptomatic lesions are soft or firm nodules 3–50 mm in diameter and variably yellowish or erythematous in color. They rarely present as linear and verrucous plaques.3,9 Development of a trichoadenoma within a dermal nevus is likely to be coincidental.10 Trichoadenoma is completely benign.

Histological features

Trichoadenoma is believed to be midway between trichoepithelioma and trichofolliculoma in terms of morphological differentiation and probably reflects differentiation towards the infundibular portion of the pilosebaceous canal.1,5,11

The epidermis is normal. Within the dermis is a well-defined fibroepithelial tumor composed of keratinous cysts and a conspicuous fibrovascular stroma (Fig. 31.17). The cyst wall is composed of squamous epithelium, which manifests epidermoid keratinization (with a granular cell layer) (Fig. 31.18). Solid epithelial islands may also sometimes be evident. There is generally no evidence of hair follicle formation, although in the verrucous variant (verrucous trichoadenoma), the cysts regularly contain vellus hairs.3,8

Trichilemmoma and Cowden’s disease

Clinical features

Trichilemmoma may be solitary or multiple.1–4 The solitary variant occasionally develops within a pre-existent nevus sebaceus, but most often it presents as a single, small, warty or smooth, skin-colored papule on the face of older adults.2–8

The presence of multiple trichilemmomas is diagnostic of Cowden’s (multiple hamartoma) disease.9–11 This disorder is characterized by multiple hamartomas and a high risk of breast and thyroid carcinoma with variable expression and age-related penetrance. The incidence of this autosomal dominant condition is estimated at approximately 1:200 000 and there appears to be a female predominance of 3:1.11

The facial lesions are skin colored and often very numerous, occurring predominantly around the mouth, nose, and ears. Patients may also develop trichilemmomas on the neck. Dermal fibromas are common and acrochorda are often present.12 Also seen in Cowden’s disease are skin-colored or brownish scaly acral keratoses with a predilection for the dorsal and ventral aspects of the hands and feet (Fig. 31.19). Punctate keratoses of the palms and soles may also be evident (Fig. 31.20). Other cutaneous manifestations include vitiligo, lipomas, hemangiomas, neurofibromas, schwannomas, and xanthomas.

Fig. 31.19 Cowden’s disease: there are numerous keratoses on the back of this male patient’s hand.

By courtesy of R. Graham, MD, and R. Emmerson, MD, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, UK.

Fig. 31.20 Cowden’s disease: note the presence of multiple plantar keratoses.

By courtesy of R. Graham, MD, and R. Emmerson, MD, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, UK.

Oral lesions are common and include papules and polyps of the tongue, palate, lips, and buccal mucous membranes (Fig. 31.21). A cobblestone appearance is characteristic, due to gingival oral fibromas (Fig. 31.22).

Fig. 31.21 Cowden’s disease: the innumerable shiny papules on this patient’s tongue are characteristic.

By courtesy of R. Graham, MD, and R. Emmerson, MD, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, UK.

Fig. 31.22 Cowden’s disease: this patient shows the typical cobblestone appearance of the buccal mucosa.

By courtesy of R. Graham, MD, and R. Emmerson, MD, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, UK.

Cowden’s disease is also associated with a wide variety of systemic manifestations. Most importantly, these include carcinomas of the breast, thyroid, and endometrium as well as macrocephaly and L’hermitte-Duclos disease (dysplastic cerebellar gangliocytoma).13–18 Other manifestations are thyroid adenomas and goiter, fibrocystic disease of the breast, renal cell carcinoma, ovarian cysts and dysgerminoma, uterine fibroids, and colonic polyps.13–17,19 The clinical diagnosis of Cowden’s disease is currently based on the constellation of major and minor criteria established by the International Cowden Consortium (Box 31.1).13 Over 90% of patients are believed to manifest a phenotype by age 20. The risk of breast cancer is estimated at 25–50% and the risk of thyroid cancer is approximately 10%.20

Pathogenesis and histological features

The susceptibility gene for Cowden’s disease has been mapped to 10q22-23 and identified as the tumor suppressor gene PTEN.21,22 Germline mutations in PTEN are present in approximately 80% of patients with this syndrome.23,24 The PTEN tumor suppressor gene is a lipid phosphatase mediating cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Germline mutations in this gene have also been observed in other syndromes including the Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, characterized by macrocephaly, lipomatosis, hemangiomatosis, and speckled penis, in addition to Proteus syndrome.25–30

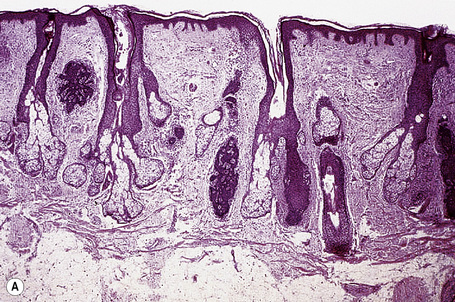

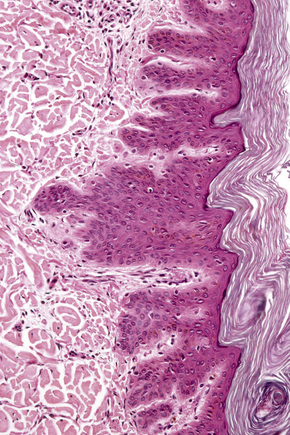

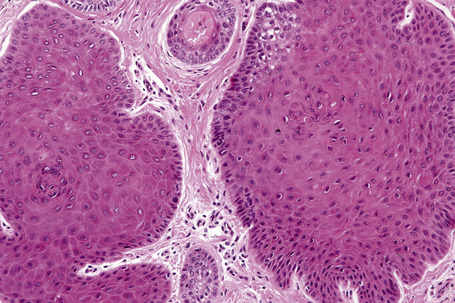

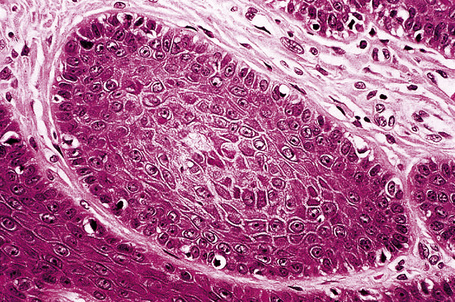

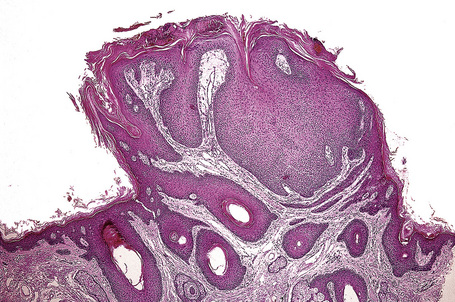

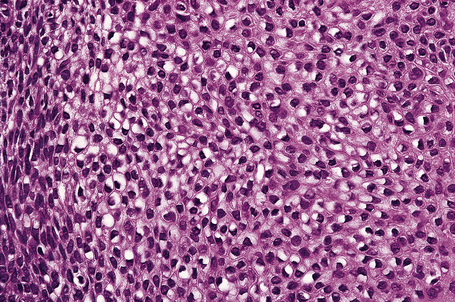

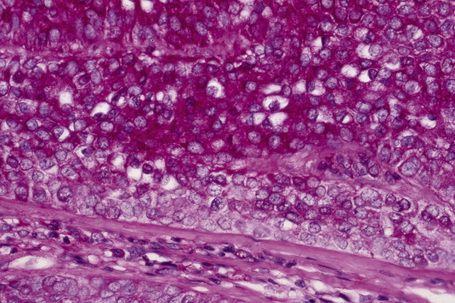

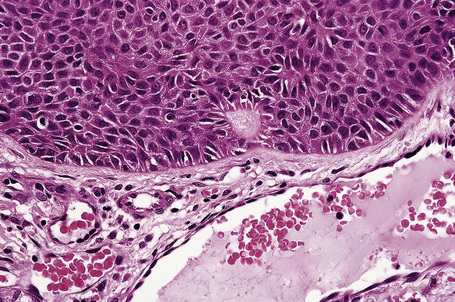

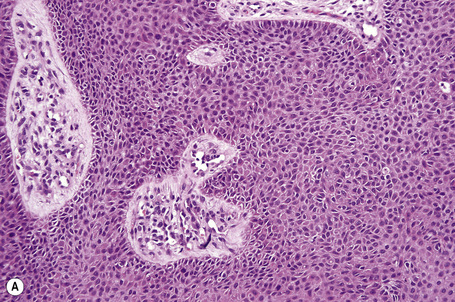

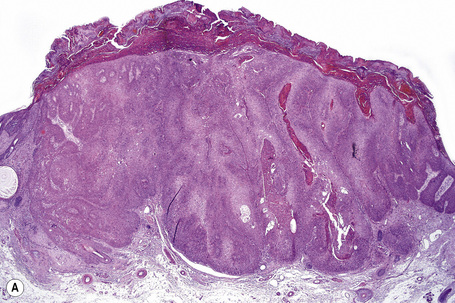

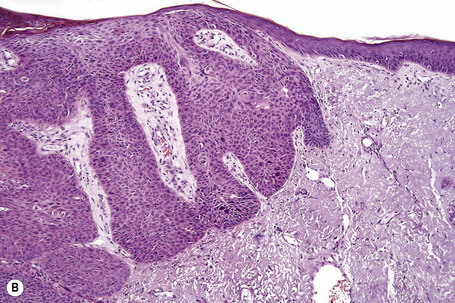

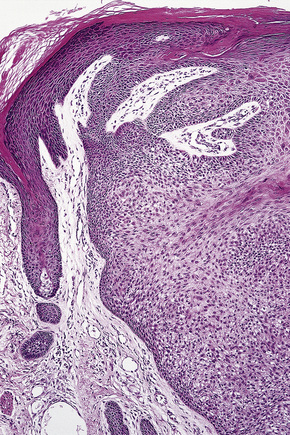

Solitary trichilemmoma, which represents proliferation of the follicular outer root sheath, appears as a small solid lobule or a group of close-set lobules connecting with the epidermis (Figs 31.23, 31.24).1,31,32 If early lesions are examined the tumor may often be seen to arise in relation to the follicular external root sheath. The lobules characteristically show peripheral nuclear palisading and are composed of uniform small cells with round or oval vesicular nuclei (Figs 31.25, 31.26). Pleomorphism is not a feature and mitoses are usually absent. A heavy glycogen content results in many of the tumor lobules having a conspicuous clear cell component (Fig. 31.27). A dense eosinophilic, diastase-resistant, PAS-positive hyaline mantle surrounding individual lobules is a typical feature (Fig. 31.28). Keratinization is usually minimal, superficial, and trichilemmal. Occasionally, however, there may be marked keratinization in association with follicular dilatation and squamous eddy formation, resulting in histological resemblance to an irritated seborrheic wart – so-called keratinizing trichilemmoma.12,33 The surface epithelium is hyperkeratotic or parakeratotic and sometimes a cutaneous horn is present (Fig. 31.29).1

Fig. 31.24 Trichilemmoma: the tumor is composed of small, uniform cells showing cytoplasmic vacuolation.

In Cowden’s disease about 50% of the facial lesions show features typical of trichilemmomas; most of the others show non-specific appearances of benign verrucous acanthomas. Occasional tumors show features intermediate between trichilemmoma and follicular infundibulum tumor or irritated seborrheic keratosis.34 Filiform wartlike lesions may also be present.34 The nonfacial keratoses show a grossly thickened keratin horn in association with a prominent granular cell layer and epidermal hyperplasia, sometimes reminiscent of acrokeratosis verruciformis or verruca vulgaris.35

The dermal fibromas often show a distinctive appearance, consisting of dense hyalinized bundles of collagen arranged in a whorled pattern reminiscent of storiform collagenoma.12,36 There is typically abundant mucin and these lesions are therefore often strongly PAS-positive.

Desmoplastic trichilemmoma

Clinical features

This rare variant of trichilemmoma, which appears to be more common in males, presents as a solitary, slowly growing, skin-colored or erythematous, dome-shaped papule.1–7 Lesions, which are usually less than 1 cm in diameter, are found predominantly on the face, although the scalp, neck, chest, and vulva may sometimes be affected.3 Occasionally, it arises within a pre-existent nevus sebaceus and coexistence with basal cell carcinoma has been described.8–10 There is no association with Cowden’s disease.

Histological features

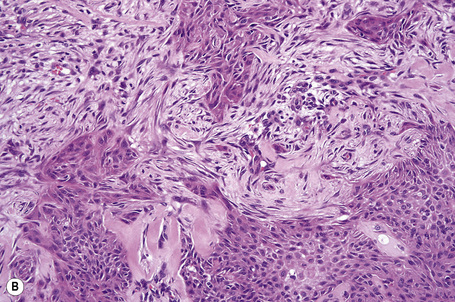

Desmoplastic trichilemmoma shows a characteristic biphasic tumor cell population. At the periphery, typical lobules of conventional trichilemmoma are present (Fig. 31.30). Towards the center, however, these merge with narrow irregular cords of smaller epithelial cells distributed in a dense, often pale eosinophilic hypocellular stroma containing diastase-resistant, PAS-positive and Alcian blue-positive material (Fig. 31.31).2,3 A chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells may be evident in the adjacent dermis.2

Trichilemmoma expresses keratin in addition to CD34, but not EMA or CEA.2,11,12

Trichilemmal carcinoma

Clinical features

Trichilemmal carcinoma is a rare tumor located predominantly on sun-exposed skin of the elderly.1 Sites of predilection therefore include the face, scalp, neck, and dorsum of the hand.2–4 The eyelid and the thigh have also rarely been involved.5,6 The age range is wide, but the tumor usually presents in patients in the seventh to ninth decades with a mean age of 71 years.1–4 Lesions are variably described as single papules, nodules, and plaques, which are frequently ulcerated and sometimes crusted. They are usually erythematous or flesh colored and measure 0.5–2.0 cm in diameter. Development of a cutaneous horn is an unusual manifestation.7 Presentation with multiple tumors and occurrence in colored races are extremely rare. Trichilemmal carcinoma has been described in association with localized pretibial pemphigoid and has arisen within burn scars, seborrheic in addition to solar keratoses, and Bowen’s disease.8–14 It may also arise in the setting of immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation.15–17

Despite histological features suggestive of likely aggressive behavior, this tumor appears to have an indolent course. Recurrence and perineural infiltration are exceedingly rare and no metastases have been reported.18

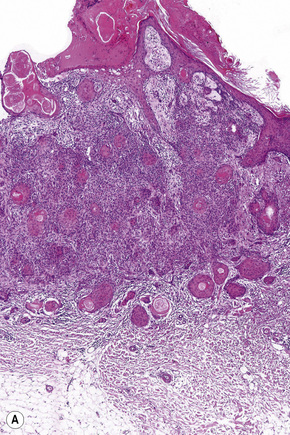

Histological features

Although the tumor can be purely intraepidermal (trichilemmal keratosis), more commonly it is associated with an invasive component, which may extend to the deep dermis or even into the subcutaneous fat.1,2,4 The intraepidermal variant is often centered on, and sometimes partially replaces, the pilosebaceous follicles with frequent involvement of the interfollicular epithelium.2

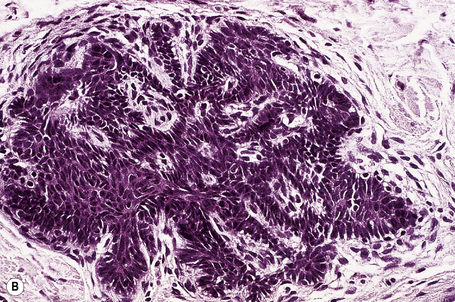

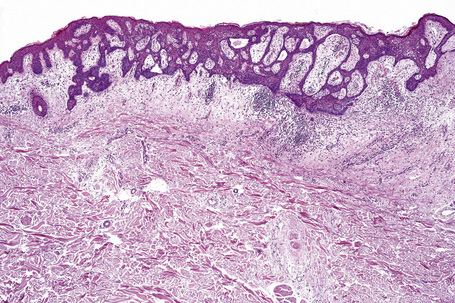

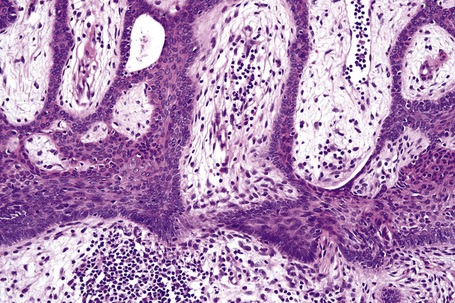

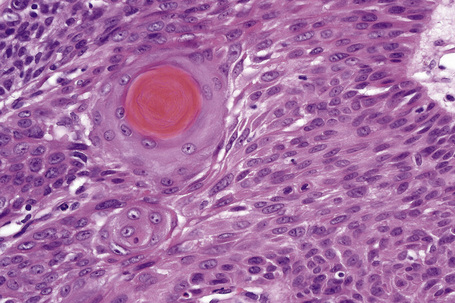

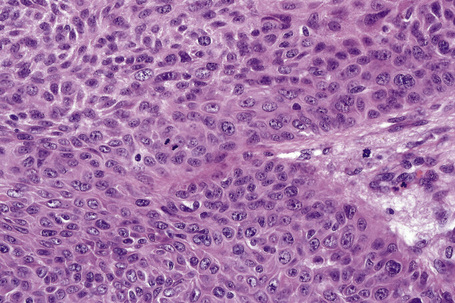

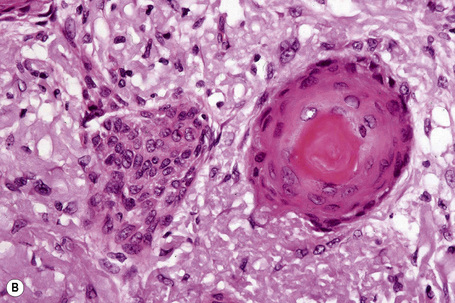

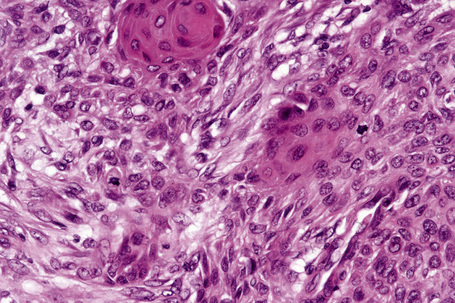

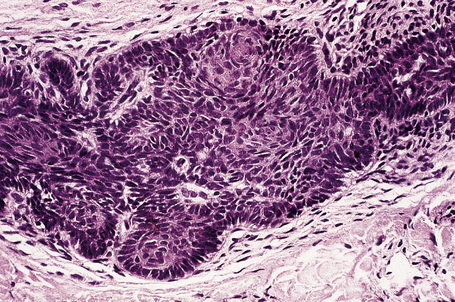

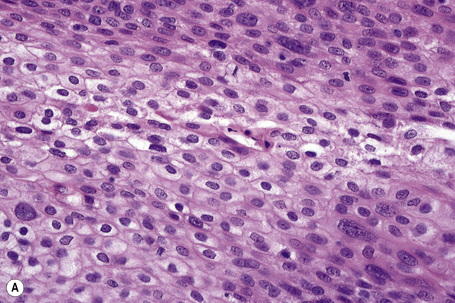

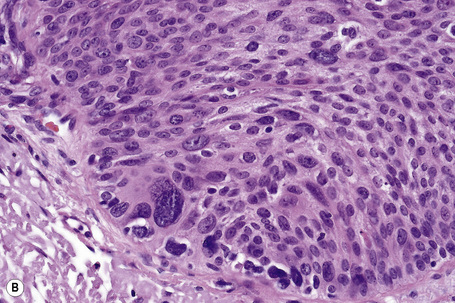

Invasive tumor commonly displays continuity with both the epidermis and hair follicles. It shows a variety of features including diffuse, lobular, and trabecular growth patterns (Fig. 31.32).4 A pushing rather than infiltrating lower border is generally present. The neoplastic epithelium consists of large cells with diastase-sensitive, PAS-positive clear cytoplasm (Fig 31.34). There is a striking tendency to trichilemmal keratinization (i.e., in the absence of a granular cell layer) (Fig. 31.33). Nuclear pleomorphism is variable, ranging from mild in well-differentiated examples through to marked in high-grade tumors. Mitotic activity is often conspicuous and abnormal forms may be found (Fig. 31.35). Large tumors commonly show foci of hemorrhage and/or necrosis.3 The periphery of the tumor lobules is characterized by nuclear palisading and subnuclear vacuolation, and sometimes a hyalin mantle is evident. Some tumors are characterized by an infiltrative growth pattern such that distinction from squamous cell carcinoma depends upon identification of pilar keratinization (Figs 31.36, 31.37). Occasional features include acantholysis, intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions, and focal pagetoid spread.1,2,4 A lymphocytic/plasma cell infiltrate is often present. Neuroendocrine differentiation with expression of chromogranin, synaptophysin, and CD56 in tumor cells is exceptional.19

Fig. 31.33 Trichilemmal carcinoma: (A) there is clear cell change; (B) there is marked nuclear pleomorphism.

Immunohistochemistry reveals high molecular weight keratin expression.1 The tumor is usually CEA and EMA negative although expression of the latter has occasionally been documented.3

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree