Chapter 27 Tumors of the conjunctiva

Introduction

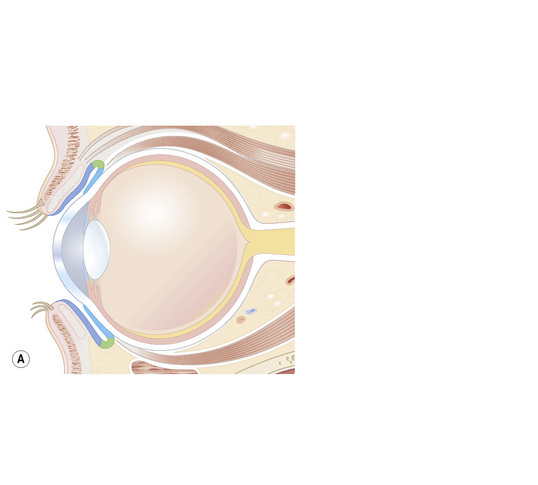

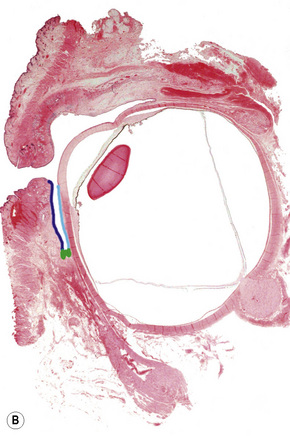

The conjunctiva is a translucent, vascularized mucous membrane that can be divided into three regions: the bulbar conjunctiva, including the corneo-conjunctival limbus, which covers the sclera in the anterior part of the eyeball; the superior, inferior, and lateral conjunctival fornices; and the palpebral conjunctiva, including the mucocutaneous transitional zone in the lid margin, which covers the posterior surface of the eyelids (Fig. 27.1).1 The conjunctiva is movable over the globe and in the fornix, where it is loosely adherent to the sclera, but fixed to the posterior surface of the eyelids, where it is markedly adherent to the tarsal plate.

Although the conjunctiva is a very thin tissue, its histological constituents can give rise to many types of tumors. It is composed of epithelium and subepithelial stroma (the substantia propria). The epithelium near the limbus is continuous with the corneal epithelium, and the epithelium in the mucocutaneous epithelial zone is continuous with the eyelid epidermis; these two sites are probably the location of conjunctival stem cells.2 The epithelial cells are stratified in a columnar manner in the fornix but tend to be cuboidal in the bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva. Goblet cells are present in the middle and superficial layers of the epithelium and are most numerous in the lower forniceal portion of the conjunctiva. They are absent in the normal limbal conjunctiva. Melanocytes are scattered throughout the basal layer of the epithelium.

Classification

In this chapter, the classification of conjunctival and corneal tumors is based on the second edition of the World Health Organization International Histological Classification of Tumors.3 Other major texts have also been consulted.4–6 The tumors discussed in this chapter are listed in Box 27.1.

Differential diagnosis

Conditions that may simulate pigmented conjunctival tumors include drug and metal deposits, mascara, foreign bodies, postinflammatory melanoses, and flat pigmentary patches from systemic conditions such as Addison’s disease.7 Inflammatory and infectious lesions such as lepromatous leprosy and sarcoidal nodules and, more commonly, allergic and other granulomatous nodules should be included in the differential diagnosis of conjunctival tumors.

Benign epithelial tumors

Squamous cell papilloma

Clinical features

Conjunctival squamous papilloma is a common benign epithelial tumor that can occur at almost any age, although it is most common in young men.1–4

It presents as sessile or pedunculated pink or red fleshy fronds of tissue or finger-like projections with irregular surfaces that sometimes appear cauliflower-like (Fig. 27.2). It is often asymptomatic, without an associated inflammatory reaction. However, large pedunculated lesions are usually symptomatic and may cause foreign body sensation, mucous secretion, hemorrhagic tears, incomplete eyelid closure or poor cosmetic appearance. Although usually solitary, it can be bilateral or multiple and may become confluent.

Conjunctival squamous papilloma often occurs in the inferior fornix or bulbar conjunctiva but may present in any part of the conjunctiva, including the palpebral conjunctiva, lid margin, caruncle, and plica semilunaris. According to one study, papillomas are located medially and inferiorly, which is explained by the direction of the flow of tears.4 Conjunctival papillomas tend to recur frequently, particularly if there are multiple lesions or the conjunctiva is infected with human papillomavirus (HPV).

Pathogenesis and histological features

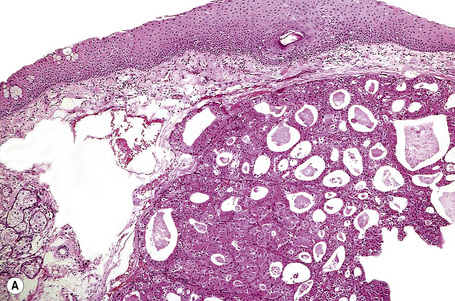

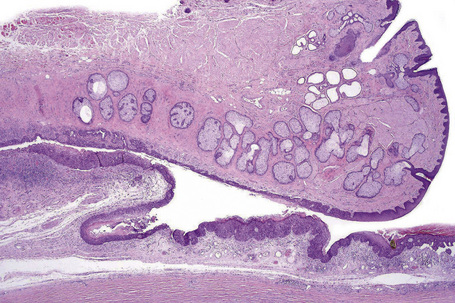

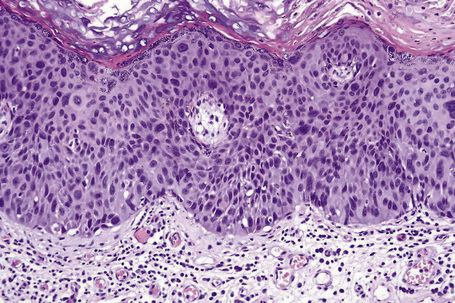

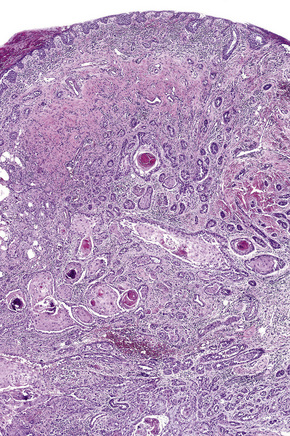

In children, squamous papillomas have been found to be associated with HPV (mostly types 6 and 11) infection of the conjunctiva. Histologically, squamous papilloma in children is composed of epithelial projections covered with nonkeratinized, acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium in which goblet cells are sometimes present. The fibrovascular cores of these lesions typically contain acute and chronic inflammatory cells (Fig. 27.3). The basement membrane is always intact. HPV may be identified using a variety of immunohistochemical and molecular techniques.5,6

Inverted papilloma

Clinical features

Inverted papillomas are exceedingly rare, solid or cystic solitary nodules that occur in the limbus, plica semilunaris, and tarsal conjunctiva. They are so named for their propensity to invaginate inward into the underlying conjunctival substantia propria instead of growing in an exophytic manner similar to other conjunctival papillomas. Some of these lesions may show a mixed inverted–exophytic papilloma.1

Pathogenesis and histological features

Unlike inverted papillomas in the nose, paranasal sinuses or lacrimal sac, conjunctival inverted papillomas do not generally exhibit locally aggressive behavior, involve extensive segments of the conjunctival epithelium or display diffuse spread or multicentricity. Therefore, conjunctival inverted papilloma should be clearly distinguished from inverted squamous papillomas of the nasal cavity and sinuses.2 However, there is a single case report documenting malignant change within an apparent inverted papilloma.3 Complete removal of this lesion is therefore recommended.

Reactive epithelial hyperplasia

Reactive epithelial hyperplasia (pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia) occurs secondary to irritation caused by concurrent or pre-existing stromal inflammation.1–3 It presents as an elevated, leukoplakic pink lesion that usually occurs in the limbic area. Histologically, it shows acanthosis, hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis and subepithelial inflammation. Mitotic figures may be present, but cytological atypia is generally absent. Clinically and histologically, reactive epithelial hyperplasia may be difficult to differentiate from conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma. An infiltrative growth pattern, marked cytological atypia, and excessive mitotic activity (including atypical forms) obviously favors the latter diagnosis.

Keratoacanthoma

Clinical features

Keratoacanthoma, a very rare variant of conjunctival reactive epithelial hyperplasia, is a rapidly growing benign, solitary, gelatinous or leukoplakic nodule on the bulbar conjunctiva that does not spontaneously regress and is surrounded by dilated blood vessels.1–3 In some cases, it shows an umbilicated center (Fig 27.4). It presents in the middle aged and has a predilection for males.4 In some cases there is a prior history of a foreign body in the eye.

Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis

Clinical features

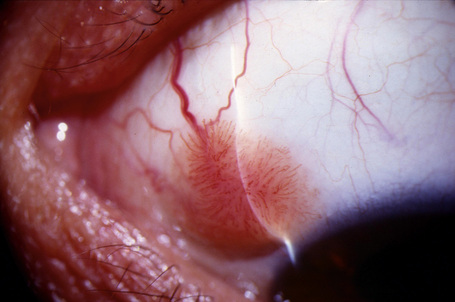

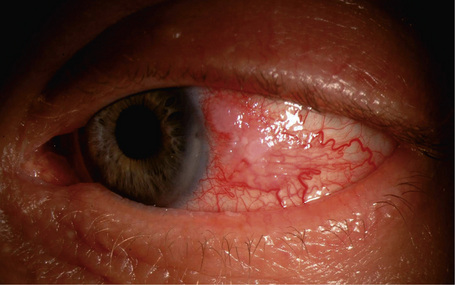

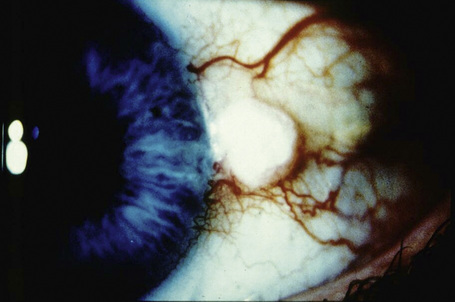

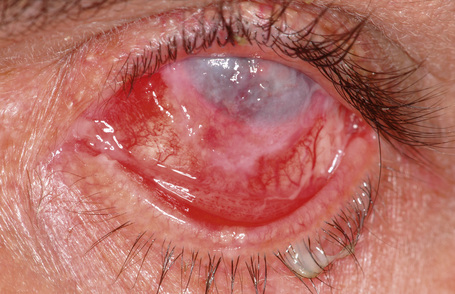

Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis (HBID) is a nonmalignant, autosomal dominant disorder, with a high degree of penetrance. It is char-acterized by bilateral elevated fleshy plaques surrounded by dilated conjunctival vessels on the nasal or temporal perilimbic bulbar conjunctiva and causes the eye to appear red (Fig. 27.5).1,2 In mild cases, HBID patients are asymptomatic; however, in severe cases, most of the bulbar conjunctiva and cornea is involved, causing corneal opacification and vascularization, leading to blindness. Patients may complain of a foreign body sensation, photophobia, and tearing. Similar lesions sometimes occur in the buccal mucosa.3 HBID occurs primarily in descendants of an inbred, isolated population of European, African-American, and Native American (Haliwa Indian) origin in Eastern North Carolina. HBID has been subsequently detected in other parts of the United States. Using genetic linkage analysis, the HBID gene has been localized to chromosome 4 (4q35).4

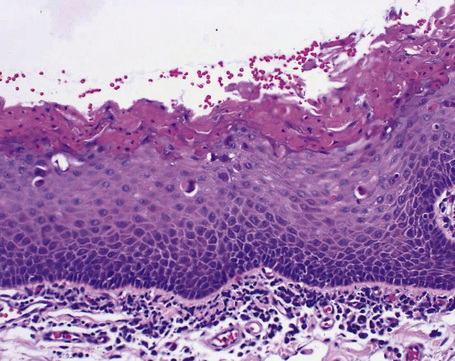

Histological features

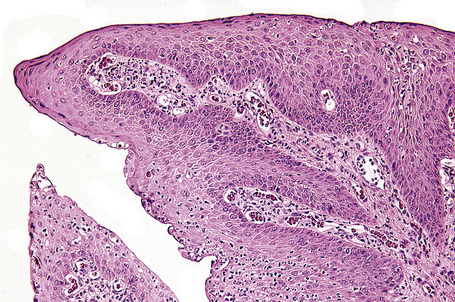

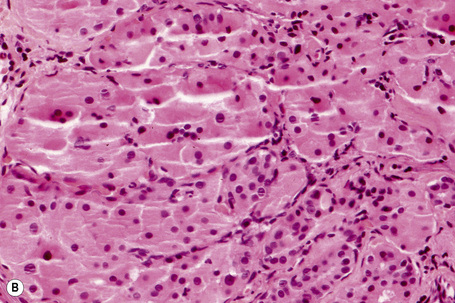

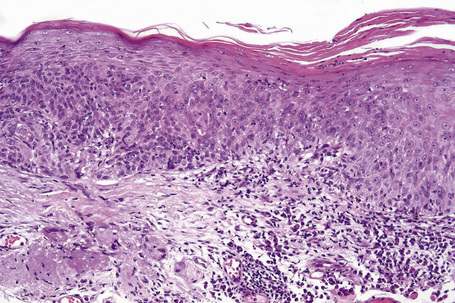

Histologically, HBID is characterized by acanthosis, prominent dyskeratosis in the surface and deep epithelium, and severe chronic inflammation in the stroma (Fig. 27.6). The basement membrane is intact.

Fig. 27.6 Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis: histology of the lesion shown in Figure 27.5 displaying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, dyskeratosis, and marked chronic inflammation in the stroma, beneath the intact basement membrane.

By courtesy of G. Klintworth, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Dacryoadenoma

Clinical features

Dacryoadenoma, an exceedingly rare conjunctival tumor that occurs in children and young adults, is a translucent pink lesion that occurs in the bulbar, forniceal or palpebral conjunctiva.1 Whether the lesion is congenital or acquired remains unknown.

Oncocytoma

Clinical features

Oncocytoma, also known as oxyphilic cell adenoma, is a rather common lesion of the lacrimal gland that often arises as a slow-growing, benign yellow–tan or reddish lesion in the caruncle or adjacent plica semilunaris and canthal conjunctiva. It presents in older individuals, usually women.1–3

Histological features

Histologically, large cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm are arranged in nests, cords or sheets that may form glandular or ductal structures (Fig. 27.7). Ultrastructurally, the cytoplasm is laden with mitochondria. Oncocytoma rarely undergoes carcinomatous transformation.

Epithelial cysts

Clinical features

Conjunctival epithelial cysts are common and may be congenital or acquired. Acquired cysts, which are more common than congenital variants, are mostly epithelial inclusion cysts that occur spontaneously or after surgical or nonsurgical trauma (Fig. 27.8).1,2 Ductal cysts, which usually arise from the accessory lacrimal gland, are also common.

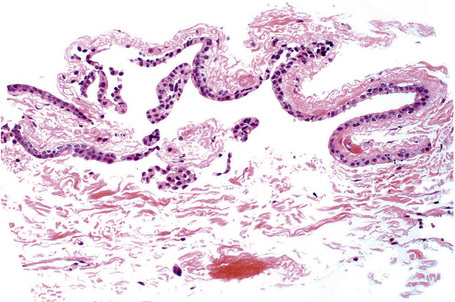

Histological features

Histologically, epithelial inclusion cysts are lined with conjunctival epithelium. Goblet cells may be present.3 The lumen can be clear, or it can contain mucinous material, epithelial debris or keratin. Ductal cysts are lined with two layers of epithelium and may contain periodic acid-Schiff-positive material (Fig. 27.9).

Keratotic plaque

Clinical features

Keratotic plaque is a white leukoplakic lesion that usually develops in the interpalpebral region of the limbic or bulbar conjunctiva (Fig. 27.10).1,2

Premalignant and malignant epithelial tumors

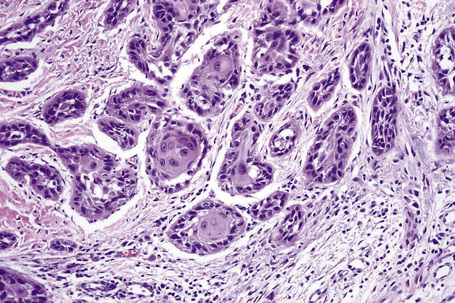

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) represent precancerous and cancerous epithelial lesions of the conjunctiva and cornea.1,2 The term includes dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Previously, intraepithelial OSSN was known as ‘intraepithelial epithelioma’, ‘Bowen’s disease of the conjunctiva’ or ‘bowenoid epithelioma’ because of its histological similarities to Bowen’s disease of the skin. Currently, these lesions are also known as conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).3

Clinical features

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia is found in all races. It is uncommon in the Northern hemisphere and is much more often seen in countries closer to the equator and in areas where people are exposed to sunlight more frequently. The incidence of OSSN in the United States is approximately 0.03 per 105 of the population.4 In Uganda, the incidence of OSSN is about 0.13 per 105, and in Australia, the incidence rate is around 1.9 per 105.1 Although OSSN occurs predominantly in adults, there are a small number of reports of childhood lesions.5 According to some studies, intraepithelial squamous neoplasia presents in patients who are 5–9 years younger than patients with invasive tumors, suggesting that precancerous CIN may become invasive SCC.6 OSSN is more common in men than women, which can be explained at least in part by the greater exposure to sunlight men receive from working outdoors.4

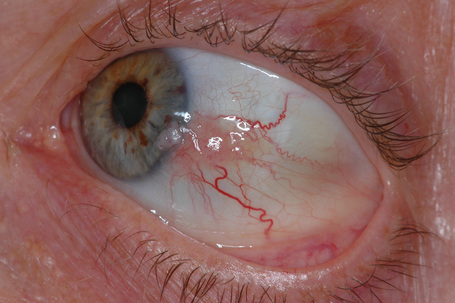

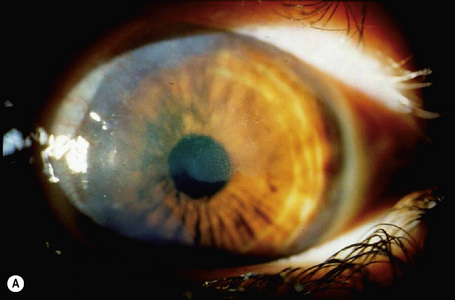

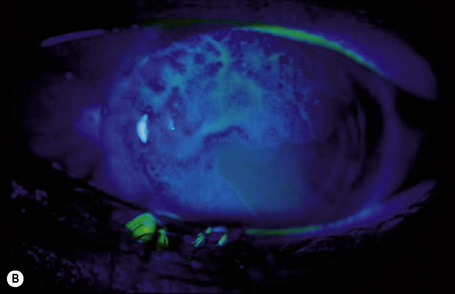

Clinically, conjunctival epithelial dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and invasive squamous carcinoma may be difficult to distinguish from one another. Although these lesions commonly arise within the interpalpebral fissure, mostly at the limbus, they can be found in any part of the conjunctiva and cornea (Figs 27.11–27.13). They present clinically in a variety of ways including gelatinous lesions with superficial vessels; papillary structures or as leukoplakia with a white keratin plaque covering the lesion.3 OSSN may also appear in a nodular form, especially when it represents an invasive squamous carcinoma, or as a diffuse lesion that may be mistaken for chronic conjunctivitis.

The clinical features of OSSN can lead to a correct diagnosis. However, because conjunctival tumors may show certain similarities, distinguishing between intraepithelial and invasive squamous neoplasia and other lesions such as pinguecula and pterygium may be difficult, especially in cases with concurrent leukoplakia or squamous papilloma. Use of fluorescein or rose Bengal staining can facilitate diagnosis by emphasizing the papillary or granular surface of part of the OSSN and help in delineating the lesion’s borders (see Fig. 27.13b). Recently, high-frequency ultrasonography has been used in the diagnosis of OSSN, particularly in estimating the depth of tumor invasion.7 However, the definitive diagnosis must be histological.

The main lesions included in the clinical differential diagnosis are pinguecula, pterygium, and squamous papilloma.3 Although OSSN usually appears as a nonpigmented lesion, pigmented conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma can be encountered. Lesions may be accompanied by redness and irritation. Visual acuity is usually not reduced unless the center of the cornea is affected. OSSN may grow within weeks to years; in most cases, however, the history is of several months.

OSSN is a low-grade malignancy.3 CIN, including dysplasia and carcinoma in situ, are precancerous lesions that rarely progress to invasive SCC. However, CIN lesions commonly recur after surgical excision, depending on the involvement of the surgical margins.3 Erie and coworkers reported that 24% of patients had a recurrence after excision of CIN and 41% of patients had a recurrence after excision of squamous cell carcinoma.6 Lee and coworkers found recurrence rates of 17% in patients with conjunctival dysplasia, 40% of patients with carcinoma in situ, and 30% in patients with SCC.1 In the same series, it was reported that 31% of patients had a second recurrence, and 8% of patients had more than two recurrences. Although most tumor recurrences develop within 2 years, later recurrences may also occur. New treatment methods including photodynamic therapy, mitomycin C, and interferon alpha-2b have reduced the recurrence rate significantly.

Although rare, intraocular invasion associated with OSSN may occur, typically in older patients who have squamous carcinoma near the corneoscleral limbus with one or more recurrences after surgical excision.8 Histopathological examination may show invasive tumor through the limbus and involving Schlemm’s canal, trabecular meshwork, anterior chamber, iris, ciliary body, suprachoroidal space, and choroid, sometimes even behind the equator. In very advanced cases, squamous carcinoma may involve the entire orbital content (Fig. 27.14).

Metastatic conjunctival squamous carcinoma is extremely rare but the parotid gland, lungs, bones, and preauricular, submandibular, and cervical lymph nodes may be involved.6,9 The main cause of metastasis is delay in diagnosis and treatment. Because regional lymph node involvement precedes the development of distant metastases, these lymph nodes should be examined on a regular basis to enable lymph node and radical neck dissection in cases with nodal involvement. Local invasion and distant metastases rarely cause death in conjunctival SCC patients.9

Pathogenesis and histological features

Exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation is a major etiologic factor in the development of OSSN.3,6 The rarity of OSSN in Europe and North America and its high incidence in sub-Saharan African countries and Australia, where people are more exposed to sunlight, suggests that ultraviolet radiation exposure plays an important role in the development of OSSN.1 Lee and coworkers reported a significant relationship between lifetime exposure to solar ultraviolet light and the development of OSSN.1 Similarly, Newton and coworkers found that the incidence of squamous carcinoma of the eye increases by 29% per unit increase in exposure to ambient solar ultraviolet radiation, equivalent to a 49% increase in incidence with each 10° decline in latitude.10 A history of actinic skin lesions such as solar keratoses and squamous carcinoma was also found to be strongly associated with the development of OSSN. Ultraviolet B rays damage DNA in human epithelial cells. Failure in DNA repair, as occurs in xeroderma pigmentosum, leads to somatic mutation and the development of cancerous cells, including OSSN.

In recent years, HPV, mainly type 16, has been demonstrated in OSSN tissue.11 HPV DNA was found in OSSN tissue using amplification with PCR and DNA sequencing, in ocular surface swabs of OSSN patients, and in studies of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue using immunohistochemistry. However, HPV may also be detected in uninvolved eyes with apparently healthy conjunctiva and in cases of persistent infection many years after successful eradication of OSSN. In a study in which antibodies against HPV were examined in OSSN, no statistically significant association between anti-HPV antibody status and the risk of conjunctival neoplasia was found, indicating that HPV alone may be incapable of causing OSSN.12

The incidence of OSSN has increased significantly since the development of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, especially in sub-Saharan African countries.13 In Rwanda, Uganda, Congo-Kinshasa, and Zimbabwe, HIV infection is strongly associated with an increase in incidence of OSSN. In these countries, OSSN tends to occur at a younger age than previously reported and appears to grow faster, indicating high aggressiveness. Although HIV infection alone seems to be a risk factor for OSSN, the interaction of HIV, ultraviolet light, and HPV appears to accelerate the development of OSSN in this part of the world.

Given the high incidence of OSSN in the limbic area, where the stem cells for the corneal and conjunctival epithelium are located, Lee and coworkers posited the limbic transition zone/stem cell theory for the development of OSSN.1 Based on Tseng’s concept of the long-living and high proliferation rate of stem cells in the limbic area, Lee and coworkers postulated that alterations in the limbic area could cause abnormal maturation of the conjunctival and corneal epithelium, resulting in OSSN.

Preoperative cytological diagnosis may help prevent removal of unnecessarily large pieces of normal conjunctiva in cases of benign lesions and avoid partial excision in cases of malignant lesions, thus sparing normal conjunctiva. One method used to diagnose OSSN preoperatively is exfoliative cytology, in which a platinum spatula, brush, or cotton-wool tip is used to obtain cells from the conjunctival surface and Papanicolaou and Giemsa stains are used to examine the cells.14 Exfoliative cytology can be used to obtain prospective cytological information about the lesion, mainly to detect malignancy; furthermore, it can be used to sample multiple sites easily and provides a convenient method of follow-up evaluation. However, because a very superficial sample – sometimes consisting of keratinized cells only – is obtained, exfoliative cytology does not enable evaluation of the structure of the lesion or the degree of tumor invasion, factors that are crucial in determining management.

Another method of obtaining cells from the surface of conjunctival lesions is impression cytology, in which several types of filter paper, such as cellulose acetate filter paper, Millipore filter paper or Biopore membrane device, are gently placed on the ocular surface to sample the most superficial cells and then fixed and stained with Papanicolaou stain.15 Impression cytology has the same advantages and disadvantages as exfoliation cytology.

Only histological evaluation of an excised lesion from an incisional or excisional biopsy can differentiate OSSN.1,2

Three variants of invasive, sometimes aggressive, conjunctival squamous carcinomas have been described.2 Spindled cell squamous carcinoma exhibits spindled cells that may be difficult to distinguish from fibroblasts. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma has mucous-secreting cells that are stained positively with special stains for mucopolysaccharides. Adenoid squamous carcinoma shows extracellular hyaluronic acid but no intracellular mucin. Because of the potential aggressiveness of these variants, which may invade the eyeball or orbital tissue or even metastasize, it is important that they are distinguished from the less aggressive conventional tumor.

OSSN arising in the corneal epithelium is rare.6,16 Some authors postulate that the corneal epithelium has the potential to undergo dysplastic and malignant change,17 while other authors think that corneal OSSN originates in the limbus. Histologically, corneal lesions are similar to those that occur in the limbus and conjunctiva. The Bowman’s layer is usually intact. Corneal CIN may rarely recur due to inadequate scraping.9,10

Benign melanocytic tumors

Conjunctival nevus

Clinical features

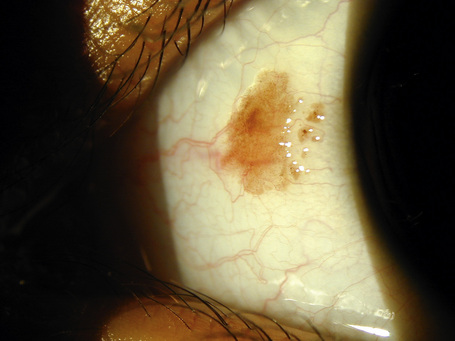

Circumscribed nevi are the most common melanocytic tumors of the conjunctiva.1,2 Although they can appear in all races, they are most commonly seen in Caucasians. Nevi that appear at birth or within the first 6 months of life are generally considered congenital, while those that appear more than 6 months after birth are regarded as acquired. Most acquired conjunctival nevi appear during the first two decades of life. Melanocytic conjunctival lesions that appear after the first two decades of life may represent PAM or melanoma.

Conjunctival nevi are typically located in the interpalpebral bulbar conjunctiva, commonly near the limbus, and rarely involve the cornea.2 The presence of melanocytic tumors in locations other than bulbar conjunctiva, plica semilunaris or caruncle is rare and should raise suspicion for PAM or melanoma.

Clinically, conjunctival nevi are discrete, variably pigmented, slightly elevated sessile lesions that typically contain cystic structures which can be seen with the naked eye or on slit-lamp biomicroscopy (Fig. 27.20). Conjunctival nevi may vary in size from tiny lesions to larger ones that occupy much of the bulbar conjunctiva. Nevi can become darker or lighter as a patient ages. They sometimes become more pink and congested because of inflammatory changes. However, conjunctival nevi usually do not change in size or color after adolescence, and such changes during adulthood should raise suspicion for malignant transformation. Conjunctival nevi can be clinically amelanotic. The presence of cystic structures may help to differentiate such conjunctival nevi from other amelanotic conjunctival lesions.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree