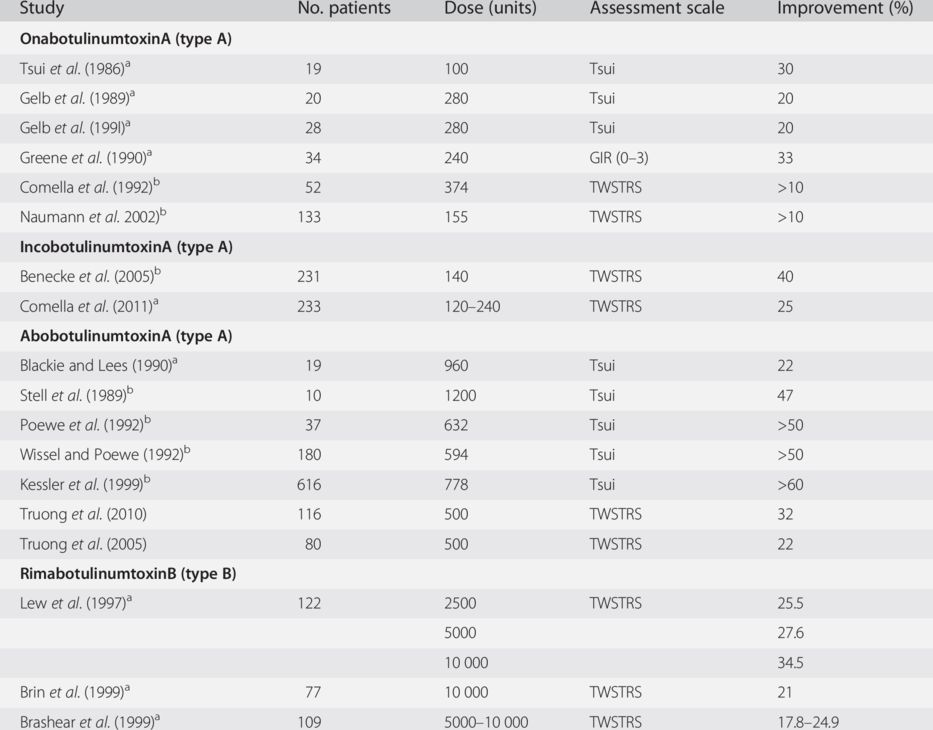

GIR, Global Improvement Rating (comparative study of two type A preparations only including responders, pain reduction 52%); TWSTRS, Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale.

a Double-blind study.

b Open study.

Use of BoNT therapy is indicated in all forms of CD. Worsening of CD while being treated with BoNT could reflect resistance to BoNT or an actual increase in severity – often, the wrong muscles have been injected. Treatment with BoNT should be initiated as early as possible, since secondary changes to the muscles involved (contractures) and of connective tissues, bony tissues and cervical discs may occur with long-standing CD.

Treatment with BoNT results in the improvement of neck posture, muscle hypertrophy and pain. The effect begins 3 to 12 days after an injection and is sustained for approximately 3 months. Injections at 3-month intervals (or longer) are thought to reduce the risk of antibodies arising to BoNT. Less experienced physicians should perform EMG recordings from sternocleidomastoid, splenius capitis, trapezius (upper portion) and levator scapulae muscles to confirm their clinical impression on the basis of head posture and muscle palpation – particularly prior to the first BoNT treatment session. Needle EMG is needed for deeper muscles, but sometimes can even be useful for superficial muscles when they are close together. It may also be useful to employ EMG when response to BoNT treatment becomes unsatisfactory, in order to determine whether injected muscles are denervated and to assist in identifying overactive muscles that may not have been injected. There may also be a change in the dystonic posturing of the head and EMG can also assist in modifying injection pattern when this occurs.

The number of injection sites within a muscle ranges from one site in smaller muscles to eight sites in larger muscles. There is little evidence to assist in determining the optimum number of injection sites. Although a study by Borodic and colleagues (1992) suggests that multiple injection sites may provide an improved result, this has not been adequately evaluated. Multiple injections with smaller doses might well also limit diffusion and reduce side effects. This might be particularly relevant in the neck, where dysphagia might result if there is excessive spread. Patients should be re-examined prior to each treatment. Muscle hypertrophy and involved muscle patterns may change over time, necessitating the alteration of injection sites over the course of repeated treatments. It is important to document the injected muscles as well as the dosage given. Upon follow-up, this can help when adjusting injection patterns and dosage.

Neck muscles and their functions

Figures 5.1 to 5.4 show the location of the muscles, which are described below.

- Iliocostalis cervicis.

The iliocostalis cervicis arises from the angles of the third, fourth, fifth and sixth ribs, and is inserted into the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C4–C6. The iliocostalis flexes the head laterally. When both iliocostalis cervicis are activated bilaterally they extend the neck dorsally (Fig. 5.1).

- Interspinalis cervicis.

These muscles lie between the spinosus processes of the cervical vertebrae. They assist in dorsal extension (Fig. 5.1).

- Intertransversarii cervicis.

These muscles are arranged in pairs, passing between the anterior and the posterior tubercles, respectively, to the transverse processes of two contiguous vertebræ. The anterior primary division of the cervical nerve separates the intertransversarii anteriores cervicis muscle from the posterior intertransversarii. They assist in the lateral and the dorsal flexion of the neck (Fig. 5.2).

- Levator scapulae.

The levator scapulae arises from the transverse processes of C1–C4 and inserts into the medial border of the scapula. This muscle elevates the medial border of the scapula while rotating the lateral angle downward. Together with the rhomboid and trapezius muscles, it pulls the scapula upward and medially, as well as tilts the neck ipsilaterally (Fig. 5.3).

- Longissimus cervicis.

The longissimus cervicis is located laterally to the semispinalis. It is the longest subdivision of the sacrospinalis and extends forward into the transverse processes of the posterior cervical vertebrae. Arising from long, thin tendons at the transverse processes of the upper four or five thoracic vertebræ, it is inserted into the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of the C2–C6. It tilts the head ipsilaterally. When the longissimus cervicis muscles are activated bilaterally, they extend the neck dorsally (Fig. 5.1).

- Longus capitis.

The longus capitis arises by four tendinous slips from the anterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C3–C6 and ascends, converging toward its fellow of the opposite side, to be inserted into the inferior surface of the basilar part of the occipital bone (Fig. 5.2).

- Longus colli.

The longus colli originates from the lower anterior vertebral bodies and transverse processes and inserts into the anterior vertebral bodies and transverse processes several segments above, flexing the head (Fig. 5.2).

- Multifidi.

The mutifidus muscle fills up the groove on each side of the spinous processes of the vertebrae. It arises, in the cervical region, from the articular processes of the lower four vertebrae and inserts into the spinous process of one of the vertebræ above. It rotates the neck contralaterally. When both multifidus are activated they extend the neck (Fig. 5.1).

- Obliquus capitis inferior.

This muscle arises from the spinous process of the axis and inserts into the inferior and dorsal part of the transverse process of the atlas. It rotates the head and the first cervical vertebra ipsilaterally (Fig. 5.1).

- Obliquus capitis superior.

The oblique capitis superior originates in the atlas mass, inserting into the lateral half of the inferior nuchal line of the occipital bone. At the atlanto-occipital joint, it extends and flexes the head ipsilaterally (Fig. 5.1).

- Rectus capitis anterior.

The rectus capitis anterior is a small muscle originating in the anterior base of the transverse process of the atlas and inserting into the occipital bone anterior to the foramen magnum, flexing the head. Furthermore, the rectus capitis anterior stabilizes the atlanto-occipital joint (Fig. 5.2).

- Rectus capitis lateralis.

The rectus capitis lateralis originates in the transverse process of the atlas and inserts into the jugular process of the occipital bone. It tilts the head laterally (Fig. 5.2).

- Rectus capitis posterior major.

This muscle arises from the spinous process of the axis, ascending into the lateral part of the inferior nuchal line of the occipital bone. As the two muscles of the two rectus capitis posterior major pass upward and laterally, they create a triangular space occupied by the recti capitis posteriores minores. The rectus capitis posterior major extends the head and rotates it to the same side (Fig. 5.1).

- Rectus capitis posterior minor.

This is a muscle of triangular form arising from the posterior arch of the atlas and inserting into the medial part of the occipital bone at, and below, the nuchal line. It extends the head (Fig. 5.1).

- Rotatores cervicis.

The rotatores cervicis arises from the transverse spinosus process and inserts into the above vertebrae, extending the neck and assisting in contralateral rotation (Fig. 5.1).

- Scalene anterior.

The scalene muscles are lateral vertebral muscles that begin at the first and second ribs and pass up into the sides of the neck. There are three of these muscles. The anterior scalene originates in the anterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C3–C6 and inserts into the first rib. It elevates the ribs for respiration and weakly rotates the head to the opposite side. When both anterior scalene muscles are contracted they flex the head forward (Fig. 5.3).

- Scalene medius.

The middle scalene arises from the transverse processes of all cervical vertebrae and inserts into the first rib (behind the anterior scalene). It bends the neck to the same side and also can flex the neck as it lies anterior to the axis (Fig. 5.3).

- Scalene posterior.

This muscle arises from the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C5 and C6 cervical vertebrae and inserts into the second and/or third rib. The action of the posterior scalene is to elevate the second rib and tilt the neck to the same side (Fig. 5.3).

- Semispinalis capitis.

The semispinalis capitis originates in the transverse processes of the T6 and C7, as well as the articular processes of C4–C6. It inserts between the superior and inferior nuchal lines of the occipital bone. The semispinalis capitis is often a cause of neck pain. Even through its main action is extension, restriction in this muscle can cause pain on rotation at the end of the range. It also rotates the head to the opposite side (Fig. 5.3).

- Semispinalis cervicis.

This muscle arises from the transverse processes of the upper five or six thoracic vertebræ. It inserts into the spinous processes of C2–C5. The semispinalis tilts the head to the same side and rotates the head to the contralateral side. Working together, the two semispinalis cervicis extend the head backward. The semispinalis capitis and cervicis and longissimus capitis are commonly overused because of their role in supporting the head when leaning forward. They are often involved in headache pain (Fig. 5.1).

- Splenius capitis.

The splenius capitis originates in the spinal process of the body of C7 and the bodies of T1 to T3. It inserts into the mastoid process. This muscle turns and tilts the head ipsilaterally. Together, the two splenius capitis muscles extend the head backward (Fig. 5.4).

- Splenius cervicis.

This muscle arises from the spinosus processes of T3–T6. It is inserted, by tendinous fasciculi, into the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C1 to C3. This muscle turns the head ipsilaterally. When both splenius cervicis are activated, they extend the head backwards.

- Sternocleidomastoid.

This muscle originates on the mastoid processes and inserts in two areas, one on the sternum and the other on the clavicle, hence the name sternocleidomastoid. It turns the head to the opposite side and the chin upward to the opposite side. It also tilts the head to the same side (Fig. 5.3).

- Trapezius.

The trapezius originates from the occipital protuberante, the ligamentum nuchae and the processes spinosus and inserts into the lateral third of the clavicle. The trapezius turns the head and neck contralaterally. It also elevates the shoulder (Fig. 5.4).

Fig. 5.1 The major neck muscles, which play some role in retrocollis but are usually not injected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree