Chapter 27 Treatment decision making in the medical encounter

the case of shared decision making

INTRODUCTION

Over the last two decades, there has been increasing interest among health researchers, clinicians and ethicists in the general topic of treatment decision making between patients and physicians and, more recently, in shared treatment decision making in particular. In this chapter we describe some of the reasons for this interest, the meaning of shared decision making, physician attitudes towards shared decision making and the development and use of decision aids to promote shared decision making. In doing so, we draw heavily on our own conceptual and empirical research on the topic of shared treatment decision making conducted over a period of more than 10 years (Charles et al 1997, 1999a).

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE SHARED DECISION MAKING APPROACH

Prior to the 1980s, the most prevalent approach to treatment decision making in North America was paternalistic, with the physician assuming the dominant role in the medical encounter (Levine et al 1992). Underlying this deference to professional authority were a number of assumptions (Charles et al 1999a). The first was that for most illnesses, a single best treatment existed and that clinical expertise and experience provided the basis for making the ‘right’ decision. Second, physicians were assumed to consistently and uniformly apply this clinical judgement when selecting treatments for their patients. Third, because of their expertise, physicians were assumed to be in the best position to evaluate treatment benefits and risks for the patient. Finally, professional ethics enjoined physicians to put the patient’s welfare first – a kind of ‘doctor knows best’ mentality.

After 1980, these assumptions began to break down. It became apparent that for an increasing number of illnesses there was no one best treatment, and a more complex decisional context emerged wherein different treatments (including the ‘do nothing’ option) had different types of trade-off between benefits and risks. Because the patient had to live with the consequences, the assumption that physicians were in the best position to evaluate these trade-offs for the patient was increasingly challenged (Eddy 1990, Levine et al 1992, Lomas & Lavis 1996). Moreover, the burgeoning literature in North America on small area variations in medical practice was beginning to show consistent evidence that physician treatments for the same disease often varied considerably across small geographic areas, and that these variations were unrelated to differences in the health status of the respective populations (Chassin et al 1986, 1987; Roos et al 1988; Wennberg et al 1987). These findings called into question the precision of medical practice, including the assumption that physicians uniformly provided the best treatment to patients with a similar disease.

Two other system level trends also cast a negative light on the autonomy of physicians in clinical practice. The first was concern over rising healthcare costs which raised the issue of accountability of physicians to patients, governments and, in the case of the US, to third party payers for clinical decisions (Katz et al 1997). The second and even more direct influence was the rise of consumerism and consumer/patient sovereignty (Charles & DeMaio 1993; Haug & Lavin 1981, 1983) in particular, as manifested in new government legislation safeguarding the rights of patients to be informed about all available treatment options (Nayfield et al 1994) and in the growing interest among many individuals and groups (e.g. physicians, patients and ethicists) to develop and advocate new approaches to treatment decision making which would incorporate a greater role for patients in this process (Gafni et al 1998).

As a result of these and other trends, the appropriateness of the paternalistic model of treatment decision making began to be questioned, and other models, such as the informed and shared approaches, were identified and advocated as potentially preferred options for treatment decision making (Charles et al 1997, 1999a; Gafni et al 1998). One major problem with this emerging literature, however, was that these concepts themselves were not clearly defined; the same words (for example ‘shared decision making’) were used to mean different things, and different labels (such as ‘informed’, ‘shared’) were used without clear distinctions in their application. Thus, while more patient involvement in treatment decision making was being advocated, it was not clear exactly what this meant or how it could be implemented. To shed light on these issues we wrote two papers in the late 1990s (Charles et al 1997, 1999a) attempting to clarify the meaning of shared decision making, to define the key components of this approach and to compare them with those of the informed and paternalistic models of treatment decision making.

THE MEANING OF SHARED DECISION MAKING

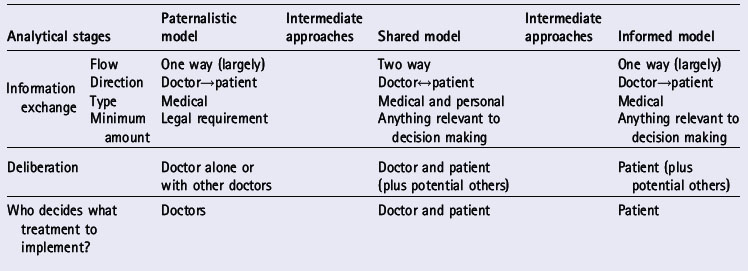

Both the informed and the shared decision making models were developed to compensate for alleged flaws in the paternalistic approach. These three models are the most widely discussed in the literature on treatment decision making. The different stages of the treatment decision making process in general are identified in Table 27.1. These stages are: information exchange, deliberation about treatment options and deciding on the treatment to implement (Charles et al 1999a). We have identified these as distinct stages, although in reality they may occur together or in an iterative process. Table 27.1 identifies the ‘ideal type’ roles that both physicians and patients play at each decision-making stage and how these differ by decision-making approach.

INFORMATION EXCHANGE

Information exchange refers to the type and amount of information exchanged between physician and patient and whether information flow is one way or two way. In the paternalistic model, the exchange is largely one way and the direction is from physician to patient. At a minimum, the physician must provide the patient with legally required information on treatment options and obtain informed consent to the treatment recommended. The patient is depicted in this model as a passive recipient of whatever amount and type of information the physician chooses to reveal. In general, this model assumes that the physician knows best and will make the best decision for the patient, without necessarily requiring any patient input.

DELIBERATION

In the informed model, the physician’s role is limited to information transfer, that is, providing the patient with information about the relevant treatment information and the risks and benefits of each. The patient alone or with input from friends and family undertakes the deliberation process to arrive at an informed decision reflecting personal values and preferences. Underlying this approach are two key assumptions. The first is that information is both necessary and sufficient to enable the patient to make the best decision. The second is that the physician should not have an investment in the decision-making process or the decision made. In other words, patient sovereignty reigns in this approach, with the physician providing technical input only, in the form of relevant scientific information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree