Tracheal Resection and Reconstruction

Alexander T. Hillel

William Grist

DEFINITION

Tracheal resection is usually performed for the external excision of tracheal stenosis or hypertrophic scarring of the trachea with critical obstruction of the airway. The term cricotracheal resection is used when the anterior section of the cricoid cartilage requires removal due to extension of the scar near the vocal folds. Tracheal resection is performed following failure of other surgical therapy, primarily endoscopic excision and dilation of tracheal stenosis. A successful tracheal resection allows the patient to avoid a lifelong tracheostomy tube.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Tracheal stenosis is primarily due to postintubation injury, although autoimmune disease can also cause subglottic stenosis. Acquired stenosis is usually secondary to pathogenic wound healing, with the formation of permanent scar tissue in the airway.

Tracheal neoplasms, including adenoid cystic and squamous cell carcinoma, or thyroid tumors with tracheal invasion are less frequent etiologies for segmental tracheal or cricotracheal resection.1

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history should be performed, including past medical history, past surgical history—including previous intubations or surgery on the trachea or esophagus, medications, allergies, and a family history of autoimmune disease.

Patients with an idiopathic etiology, who have not undergone intubation, or those with a history/family history of autoimmune disease should have an autoimmune serum panel.

A detailed medical history for comorbidities that could affect recovery following resection includes diabetes, coronary artery disease, and lung disease including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and tracheobronchial malacia. Severe COPD and tracheobronchial malacia may necessitate the need for tracheostomy even following successful resection.

Patients who had multiple previous procedures, especially open tracheostomies or cervical tracheoesophageal fistula repair, may have extratracheal fibrosis, making dissection more challenging and increasing the risk of injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN).

Table 1: Absolute and Relative Contraindications for Tracheal Resection

Active autoimmune diseases affecting the airway (Wegener’s granulomatosis, relapsing polychondritis)

Stenosis extending to include the vocal folds

Stenosis greater than half the length of the trachea (relative contraindication)

Concurrent laryngeal stenosis (relative contraindication)—tracheostomy will need to remain in place until laryngeal stenosis is addressed.

Thorough evaluation of vocal fold mobility is recommended to document preoperative function. Patients often have multiple levels of stenosis, and glottic narrowing due to a second stenosis at level of vocal folds (relative contraindication) may limit the efficacy of successful tracheal resection.

Accurate understanding of the length of stenosis will impact the necessity of surgical release maneuvers. These are rarely required for stenosis less than 5 cm.

Contraindications for tracheal resection are listed in Table 1.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

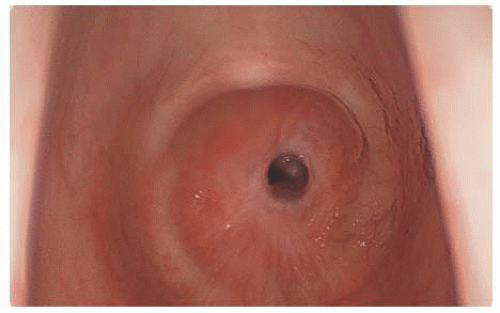

Bronchoscopy is required to accurately map out the stenosis, including its length, width, and distance from the vocal folds and carina when appropriate. Bronchoscopy is usually performed in the operating room or endoscopy suite (FIG 1); however, with appropriate topical anesthesia, in-office bronchoscopy can provide similar results and avoid a trip to the operating room.

As detailed in the preceding section, laryngoscopy or stroboscopy, when indicated, should be performed to assess preoperative vocal fold mobility and the presence of laryngeal stenosis.

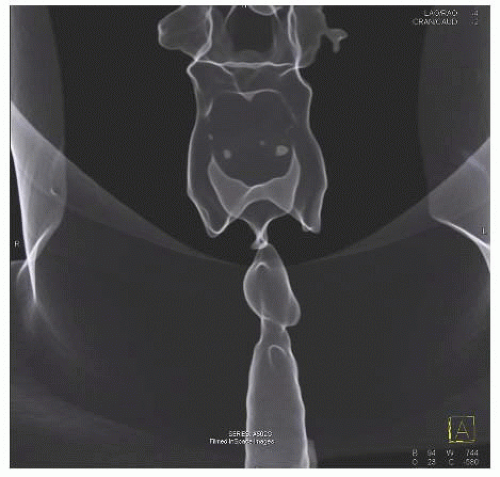

Computed tomography (CT) can provide key anatomic detail of the trachea, especially of the external trachea and adjacent vasculature. Three-dimensional CT provides excellent reconstructions of the tracheal and bronchial airways (FIG 2).

If the patient complains of dysphagia, a modified barium swallow study may yield relevant results especially if the patient requires infra- or suprahyoid laryngeal release maneuvers, which will adversely affect swallowing postoperatively.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

When relevant, preoperative discussion between surgical teams about the extent of the stenosis is recommended. If the otolaryngologist represents the primary surgeon and repair of the stenosis may require a sternotomy, thoracic surgery should be consulted.

FIG 2 • Three-dimensional sagittal CT image of cervical tracheal stenosis with dilated segment proximal to stenosis.

Similarly, if it is a primary thoracic team performing surgery and the stenosis requires a suprahyoid release maneuver, preoperative inclusion of otolaryngology team is recommended. Use of an NIM™ RLN monitoring endotracheal tube (ETT) is recommended to allow for monitoring of the RLN during dissection.

Having a second anesthesia circuit in a sterile sleeve allows for easy control of the airway when the anode tube is placed in the distal trachea following the tracheal cuts.

Positioning

An inflatable shoulder roll should be inflated to provide complete neck extension and deflated prior to closure.

Initial bronchoscopy may be performed with the bed rotated 90 degrees from the anesthesia team to allow the surgical team to dilate the stenosis in order to place an ETT.

Following intubation, the bed should be rotated another 90 degrees to have the head 180 degrees from anesthesia.

This allows for adequate room around the head and neck. If tracheostomy tube cannot be replaced with placement of an ETT following dilation, replace the tracheostomy tube with an anode tube to remove the flange from the operative field.

TECHNIQUES

BRONCHOSCOPY

Initial bronchoscopy is recommended to assess the stenosis; dilate and place an ETT prior to resection. We encourage perioperative placement of an ETT in patients with tracheostomies to remove the tracheostomy tube from the surgical field.

A key determination on bronchoscopy is the proximity of the stenosis to the vocal folds. If the proximal portion is within 2 cm of the superior aspect of the vocal folds, the cricoid will usually need to be included in the excision, which will influence the location of the initial tracheal incision.

PLACEMENT OF INCISION

A low transverse neck incision should be placed in a neck crease below the cricoid cartilage extending from the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscles on each side of the neck.

If there is existing tracheostomy skin scar, the incision should include the scar around the tracheostomy site in an ellipse fashion.

SKIN INCISION AND RAISING OF FLAPS

An incision is extended deep to the platysma, and inferior and superior subplatysmal flaps should be elevated from the sternal notch to the hyoid superiorly.

The authors are proponents of the Mayfield thyroid retractor to provide adequate exposure.

EXPOSURE OF TRACHEA

The sternohyoid and the sternothyroid muscles should be dissected and retracted laterally to expose the thyroid isthmus, which should be transected and reflected laterally.

This provides exposure of the trachea, which should be skeletonized with blunt dissection to free up the anterior ligamentous attachments to just above the carina. This assists in for tension-free anastomosis. Lateral dissection should be limited to maintain the vascular supply.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree