Patient Story

A 55-year-old woman presents for follow-up of hypertension. She has been smoking 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day since her late teens and reports that she is now ready to stop smoking. She realizes that smoking is bad for her health and does not like how smoking causes more wrinkles on the face (Figure 236-1). She has tried unsuccessfully to stop smoking on 3 different occasions using nicotine replacement therapy (patches and gum) and bupropion. She has no history of a psychiatric or seizure disorder. She would like to try stopping smoking using varenicline. She is also willing to return for 4 follow-up sessions at weekly intervals. She agrees to call a stop smoking telephone helpline (1-800-QUIT NOW) for counseling help. The patient tolerates the varenicline well and is able to stop successfully without any adverse effects. Two years after treatment she continues to be abstinent and very glad of this outcome. The clinician used elements of the “5 A’s” model for treating tobacco use and dependence to successfully help this patient quit smoking. (Table 236-1)

Ask about tobacco use. | Identify and document tobacco use status for every patient at every visit. |

Advise to quit. | In a clear, strong, and personalized manner, urge every tobacco user to quit. |

Assess willingness to make a quit attempt. | Is the tobacco user willing to make a quit attempt at this time? |

Assist in quit attempt. | For the patient willing to make a quit attempt, offer medication and provide or refer for counseling or additional treatment to help the patient quit. For patients unwilling to quit at the time, provide interventions designed to increase future quit attempts. |

Arrange followup. | For the patient willing to make a quit attempt, arrange for followup contacts, beginning within the first week after the quit date. For patients unwilling to make a quit attempt at the time, address tobacco dependence and willingness to quit at next clinic visit. |

Introduction

Half of all deaths (more than 440,000) in the United States are attributed to tobacco addiction, including those caused by passive smoking. Tobacco addiction is a chronic disease, often developed during adolescence and early adulthood, that requires ongoing assessment and repeated intervention. There are effective treatments that can significantly increase rates of long-term abstinence. There are also effective preventive interventions that can prevent the initiation of tobacco use and reduce its prevalence among youth.

Epidemiology

- Among adults who become daily smokers, nearly all first use of cigarettes occurs by 18 years of age (88%), with 99% of first use by 26 years of age.1

- Almost 1 in 4 high school seniors is a current (in the past 30 days) cigarette smoker, compared with 1 in 3 young adults and 1 in 5 adults. Approximately 1 in 10 high school senior males is a current smokeless tobacco user, and approximately 1 in 5 high school senior males is a current cigar smoker.1

- Significant disparities in tobacco use remain among young people nationwide. The prevalence of cigarette smoking is highest among American Indians and Alaska Natives, followed by whites and Hispanics, and then Asians and blacks. The prevalence of cigarette smoking is also higher among lower socioeconomic status youth.1

- The latest data show the use of smokeless tobacco is increasing among white high school males, and cigar smoking may be increasing among black high school females.1

- Concurrent use of multiple tobacco products is prevalent among youth. Among those who use tobacco, nearly one-third of high school females and more than one-half of high school males report using more than 1 tobacco product in the last 30 days.1

- Persons with psychiatric diagnoses have much higher rates of smoking than the general population.2

- Persons with mental illness and/or substance abuse consume 44% of all cigarettes sold in the United States, despite being only 22% of the population.2

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- The evidence on the mechanisms by which smoking causes disease indicates that there is no risk-free level of exposure to tobacco smoke.3

- Inhaling the complex chemical mixture of combustion compounds in tobacco smoke causes adverse health outcomes, particularly cancer and cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, through mechanisms that include DNA damage, inflammation, and oxidative stress.3

- There is sufficient evidence to infer that a causal relationship exists between active smoking and (a) impaired lung growth during childhood and adolescence; (b) early onset of decline in lung function during late adolescence and early adulthood; (c) respiratory signs and symptoms in children and adolescents, including coughing, phlegm, wheezing, and dyspnea; and (d) asthma-related symptoms (e.g., wheezing) in childhood and adolescence.1

- The evidence is suggestive but not sufficient to conclude that smoking by adolescents and young adults is not associated with significant weight loss, contrary to young people’s belief.1

- Through multiple defined mechanisms, the risk and severity of many adverse health outcomes caused by smoking are directly related to the duration and level of exposure to tobacco smoke.3

- Sustained use and long-term exposures to tobacco smoke are caused by the powerfully addicting effects of tobacco products, which are mediated by diverse actions of nicotine and perhaps other compounds, at multiple types of nicotinic receptors in the brain.3

- Nicotine stimulates the release of multiple neurotransmitters, including dopamine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, glutamate, serotonin, β-endorphin, and γ-aminobutyric acid.4

- Low levels of exposure, including exposures to secondhand tobacco smoke, lead to a rapid and sharp increase in endothelial dysfunction and inflammation, which are implicated in acute cardiovascular events and thrombosis.3

- There is insufficient evidence that product modification strategies to lower emissions of specific toxicants in tobacco smoke reduce risk for the major adverse health outcomes.3

Risk Factors

Given their developmental stage, adolescents and young adults are uniquely susceptible to social and environmental influences to use tobacco.

- Socioeconomic factors and educational attainment influence the development of youth smoking behavior. The adolescents most likely to begin to use tobacco and progress to regular use are those who have lower academic achievement.1

- The evidence is sufficient to conclude that there is a causal relationship between peer group social influences and the initiation and maintenance of smoking behaviors during adolescence.1

- Affective processes play an important role in youth smoking behavior, with a strong association between youth smoking and negative affect.1

- The evidence is suggestive that tobacco use is a heritable trait, more so for regular use than for onset. The expression of genetic risk for smoking among young people may be moderated by small-group and larger social-environmental factors.1

Diagnosis

- History—Most tobacco users express a desire to stop using tobacco but report repeated failures in their attempts. All patients should be asked if they use tobacco and should have their tobacco use status documented on a regular basis. Evidence shows that clinic screening systems, such as expanding the vital signs to include tobacco use status, or the use of other reminder systems, such as chart stickers or computer prompts, significantly increase rates of clinician intervention.5 SOR A

- Physical—Individuals with tobacco addiction may easily be detected by:

- Distinctive odor of tobacco smoke.

- Smoker’s cough.

- Raspy or hoarse voice (see Chapter 36, The Larynx [Hoarseness])

- Pack of cigarettes in the front pocket of the shirt.

- Wrinkles in excess of what would be expected for their age (Figure 236-2).

- Distinctive odor of tobacco smoke.

- Smoker’s face is described as:

- “Lines or wrinkles on the face, typically radiating at right angles from the upper and lower lips or corners of the eyes, deep lines on the cheeks, or numerous shallow lines on the cheeks and lower jaw.” (Figure 236-2.)

- “A subtle gauntness of the facial features with prominence of the underlying bony contours.”6

- “Lines or wrinkles on the face, typically radiating at right angles from the upper and lower lips or corners of the eyes, deep lines on the cheeks, or numerous shallow lines on the cheeks and lower jaw.” (Figure 236-2.)

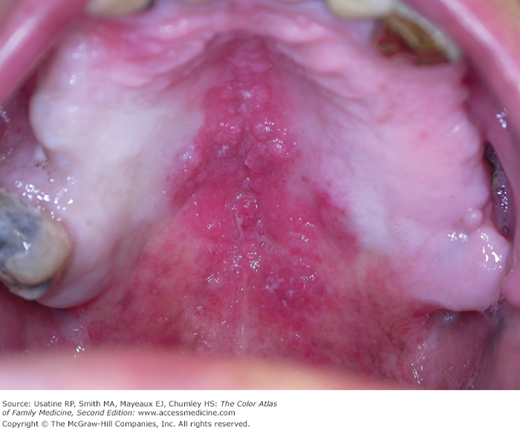

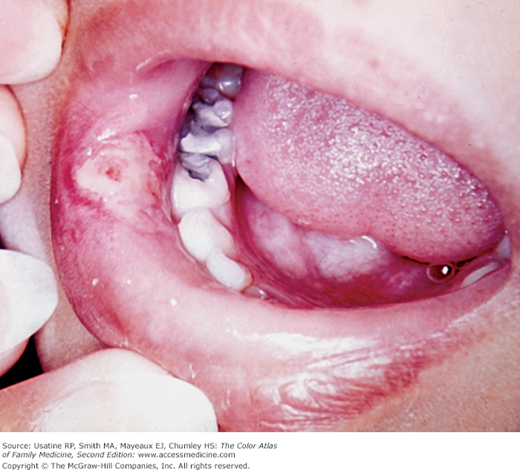

- The oral cavity of smokers often shows signs of prolonged exposure to tobacco in the form:

- Yellow and brown teeth (Figures 236-3, 236-4, and 236-5).

- Angular cheilitis (Figure 236-3) (see Chapter 32, Angular Cheilitis).

- Gingivitis and periodontitis (Figure 236-4) (see Chapter 39, Gingivitis and Periodontal Disease).

- Yellow and brown teeth (Figures 236-3, 236-4, and 236-5).

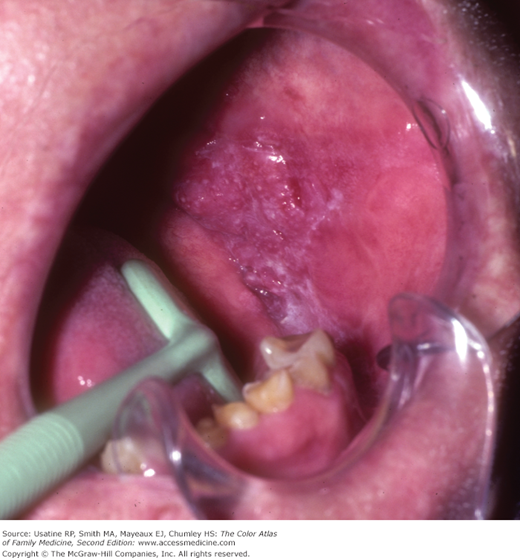

- There may be other serious conditions within the oral cavity such as:

- Leukoplakia—A pre-malignant condition (Figure 236-5) (see Chapter 42, Leukoplakia).

- Nicotine stomatitis (Figure 236-6).

- Squamous cell carcinoma (Figures 236-7 and 236-8) (see Chapter 43, Oropharyngeal Cancer).

- Leukoplakia—A pre-malignant condition (Figure 236-5) (see Chapter 42, Leukoplakia).

- Withdrawal symptoms—Symptoms associated with tobacco addiction withdrawal include a dysphoric or depressed mood, insomnia, irritability, frustration or anger, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, decreased heart rate, and increased appetite or weight gain.7 None of the withdrawal symptoms are life-threatening, as they can be with other drugs like alcohol and opiates. Their intensity peaks during the first week and most last no more than 2 to 4 weeks following abstinence.8

- Complications—Continuing use of tobacco causes multiple cancers and the development and/or exacerbation of multiple chronic diseases as summarized in Figure 236-9.

- Emphysema may significantly impair lung function and lead to death (see Chapter 56, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease). Centrilobular emphysema occurs with carbon deposits in the destroyed lung tissue.

Figure 236-2

Smoker’s face described as “one or more of the following: (a) lines or wrinkles on the face, typically radiating at right angles from the upper and lower lips or corners of the eyes, deep lines on the cheeks, or numerous shallow lines on the cheeks and lower jaw. (b) A subtle gauntness of the facial features with prominence of the underlying bony contours.6 (Courtesy of Usatine R, Moy R, Tobinick E, Siegel D. Skin Surgery: A Practical Guide. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree