Thyroid and Parathyroid

Tatjana Antic

Adriana Acurio

Jerome B. Taxy

Introduction: Thyroid Frozen Section

Historically, intraoperative consultation by frozen section has been used to establish a definitive diagnosis in the surgical treatment of thyroid nodules. The justification for this practice has been that a frozen section diagnosis of malignancy allows for an immediate completion thyroidectomy, thus avoiding an additional procedure. Although, in the past, a near total or total thyroidectomy was reserved for thyroid malignancies only, presently there is a significant literature suggesting that total or near total thyroidectomy is considered a treatment of choice for benign thyroid conditions (1,2,3,4,5). The advent of fine needle aspiration (FNA) has changed the management of thyroid nodules. The American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines consider FNA as the most accurate and cost-effective method for the management of thyroid nodules (6). FNA is most accurate for certain thyroid malignancies such as papillary and medullary thyroid carcinomas, and for recognizing most benign follicular processes; for example, colloid nodules and thyroiditis, therefore possibly avoiding surgery altogether (6,7). In current practice, the reliance on a tissue diagnosis derived from the frozen section must also be supplemented by imprint preparations. Since a diagnosis of follicular carcinoma is not possible by FNA, cellular follicular lesions unaccompanied by concomitant quantities of colloid, referred to in the Bethesda terminology as follicular lesions of undetermined significance (FLUS), suspicious for follicular neoplasm or follicular neoplasm (8) are surgically approached. The questions, however, remain: (i) How necessary is an immediate diagnosis especially if a total thyroidectomy is planned even for a benign condition? (ii) What constitutes the thoroughness of sampling for that tissue diagnosis?

Experience has shown that there are diagnostic challenges in thyroid histopathology even when paraffin-embedded sections of an entire lesion are available. For pathologists, a frozen section of a mass lesion in the thyroid represents a technically less than ideal histologic preparation of inherent limited sampling but with potentially major clinical consequences. Attempting a diagnosis under these circumstances may appear ill advised, and it may occasionally seem to the pathologist that the clinical physicians caring for patients with thyroid disease do not adequately grasp

this. It is not surprising, therefore, that there is occasional contention between surgeons and pathologists and even disagreement among pathologists about the appropriate use of intraoperative diagnosis in thyroid surgery. The irony of the preceding is that the historical accuracy of thyroid frozen section has been quite remarkable.

this. It is not surprising, therefore, that there is occasional contention between surgeons and pathologists and even disagreement among pathologists about the appropriate use of intraoperative diagnosis in thyroid surgery. The irony of the preceding is that the historical accuracy of thyroid frozen section has been quite remarkable.

It is acknowledged that the diagnostic utility of frozen section is limited for cellular follicular lesions, an aspect frequently cited as an example of inaccuracy and a reason to avoid frozen section in this context (9,10,11,12). However, it could also be argued that the combination of FNA and frozen section generally provides the greatest level of intraoperative diagnostic accuracy. The preoperative FNA diagnosis and the limitations of frozen section notwithstanding, definitive surgical treatment is still based on a tissue examination. Also, irrespective of one’s opinion on this issue, frozen section requests are a reality of daily practice. This chapter will not resolve this controversy but will discuss the indications, limitations, and diagnostic challenges encountered in the intraoperative examination of thyroid and parathyroid lesions.

Thyroid Frozen Section: Intraoperative Questions

The frozen section in thyroid disease concerns these major areas.

Confirmation and tissue diagnosis of a clinical thyroid mass, best applied to those with no preoperatively established malignant diagnosis by FNA.

Examination of a regional lymph node for the presence of metastatic disease.

Identification of unanticipated neck masses encountered during surgery; for example, thymic remnants, aberrant parathyroids, or enlarged lymph nodes.

Each point relates to the potential for altering the surgical procedure. Confirmation of a malignant thyroid tumor commits the patient to a total thyroidectomy, much easier to do in an unoperated neck than in a previously explored and possibly fibrotic neck. Regional node metastases are arguably less pressing since formal neck dissections are not indicated in thyroid cancer, but the presence or absence of a nodal metastasis may suggest stopping or expanding the procedure. The identification of unanticipated masses may further individualize the surgical treatment.

Thyroid Frozen Section: Gross Specimen Handling

The best initial examination is that of the gross specimen. A lobectomy is the most common surgical approach to a thyroid mass either having had no preoperative FNA diagnosis of malignancy or with a diagnosis of FLUS (suspicious for follicular neoplasm) or follicular neoplasm. In the age of FNA, enucleations and needle core biopsies are of controversial appropriateness and are fortunately uncommon. The gross specimen is routinely inked, weighed, and serially sectioned perpendicular to the long axis of

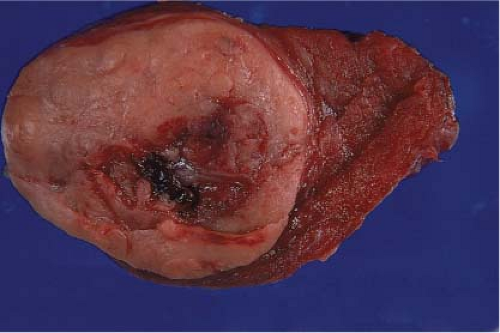

the lobe (“breadloaf” fashion), carefully maintaining the capsular integrity associated with the lesion and maximizing inspection of the capsular–parenchymal interface. For goitrous specimens, one coronal cut will expose a complete hemisected lobar plane which is then breadloafed. This approach will facilitate eventual thorough lesion sampling with adjacent capsular tissue. Important gross features that guide the histologic sampling include the sizes and colors of the lesion(s); circumscription; the presence of cysts, hemorrhage, stellate shape, fibrous components, or necrosis. For example, a solitary circumscribed mass is consistent with a follicular adenoma; a solid brown lesion with a central scar is highly compatible with a Hürthle cell tumor (oncocytoma) (Fig. 11.1, e-Fig. 11.1). A stellate gritty gray mass, with or without encapsulation and occasionally quite small, is suggestive of papillary carcinoma (Fig. 11.2, e-Figs. 11.2 and 11.3). The best sample to take for frozen section study is one that includes the tumor–parenchymal interface and the peripheral external surface.

the lobe (“breadloaf” fashion), carefully maintaining the capsular integrity associated with the lesion and maximizing inspection of the capsular–parenchymal interface. For goitrous specimens, one coronal cut will expose a complete hemisected lobar plane which is then breadloafed. This approach will facilitate eventual thorough lesion sampling with adjacent capsular tissue. Important gross features that guide the histologic sampling include the sizes and colors of the lesion(s); circumscription; the presence of cysts, hemorrhage, stellate shape, fibrous components, or necrosis. For example, a solitary circumscribed mass is consistent with a follicular adenoma; a solid brown lesion with a central scar is highly compatible with a Hürthle cell tumor (oncocytoma) (Fig. 11.1, e-Fig. 11.1). A stellate gritty gray mass, with or without encapsulation and occasionally quite small, is suggestive of papillary carcinoma (Fig. 11.2, e-Figs. 11.2 and 11.3). The best sample to take for frozen section study is one that includes the tumor–parenchymal interface and the peripheral external surface.

The Thyroid: Frozen Section and its Interpretation

Total or near-total thyroidectomy specimens for cancer are generally accompanied by a preoperative diagnosis of carcinoma per FNA. In such cases, the intraoperative consultation is not indicated since the definitive

surgical procedure has already been done. Nonetheless, some surgeons request a frozen section examination to confirm a prior FNA diagnosis. This potential conflict is, at present, an intramural issue and the appropriateness of this examination should be worked out individually between the surgeon and the pathologist. For lobectomy specimens that lack a definitive preoperative diagnosis, frozen section examination may be useful.

surgical procedure has already been done. Nonetheless, some surgeons request a frozen section examination to confirm a prior FNA diagnosis. This potential conflict is, at present, an intramural issue and the appropriateness of this examination should be worked out individually between the surgeon and the pathologist. For lobectomy specimens that lack a definitive preoperative diagnosis, frozen section examination may be useful.

Figure 11.2 Papillary carcinoma. Partially encapsulated “colloid nodule” with a firm gray-white, noncircumscribed mass extending away from the thin fibrous capsular band. |

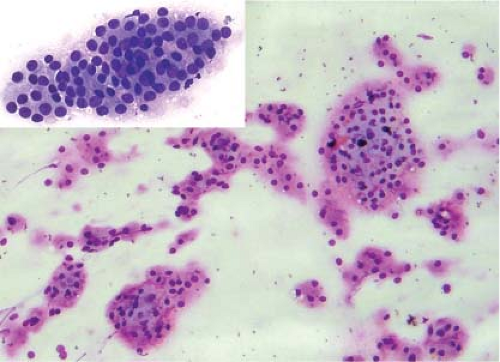

If a frozen section is to be done, a simultaneous cytologic imprint preparation is essential (13,14). The imprint provides cytomorphologic features that are less well represented on the frozen preparation, such as the nuclear grooves and pseudoinclusions characterizing papillary carcinoma. To prepare an imprint slide, a fresh cut through the tissue is made. Excess blood or fluid is blotted off and the tissue is firmly touched against a glass slide. If the slide is to be stained by H&E, it must be fixed immediately in alcoholic formalin to avoid drying artifacts. This stain best maintains nuclear detail and is tinctorially similar to the actual frozen section. When using Diff-Quick or Giemsa staining, the slide is air-dried first. This stain may not as effectively enhance the nuclear detail; however, it preserves acellular background material such as colloid and amyloid. Employing both stains is redundantly beneficial but does require some visual adjustments, easily made with increasing experience. Imprint preparations reviewed concurrently with the frozen section further increase the diagnostic accuracy, especially in cases of papillary carcinoma. In benign colloid nodules or thyroiditis, the imprint findings reflect similar features as seen in the FNA. In the case of follicular neoplasms, cytologic preparations (including imprints) will not distinguish between follicular adenoma and follicular carcinoma, since the diagnosis depends on the histologic recognition of vascular invasion. Small lesions (<5 mm) should have imprints made but should not be frozen.

Colloid Nodules and Follicular Neoplasms

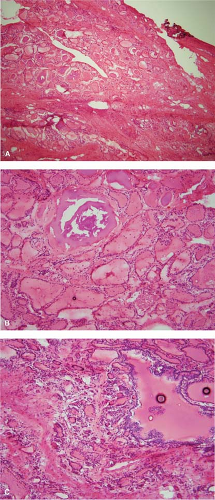

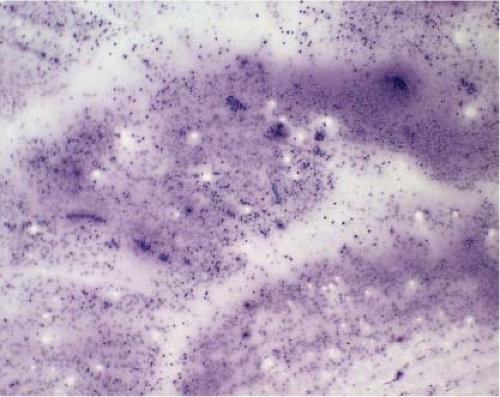

Colloid nodules are grossly multiple and may result in an enlarged or goitrous gland. On cross section, there is often partial encapsulation of the nodules (Fig. 11.3). Degenerative changes in the form of hemorrhage, calcification, cyst formation, and fibrosis are common (e-Fig. 11.4A–C). These areas should be avoided for frozen section sampling (15,16). Imprint preparations show relatively scant bland follicular cells and abundant background colloid (Fig. 11.4). Occasional admixtures of Hürthle cells (oncocytes) are also common and reassure that the lesion is benign (Fig. 11.5). The histologic picture is varied and technically complicated by tissue folds or the tendency of colloid to exhibit “chatter” artifact. Dilated follicles are lined by flat atrophic cells and alternate with smaller follicles lined by plumper cells (Fig. 11.6A–C). Occasionally, there are also benign papillary-like formations that protrude toward the center of a cystically dilated follicle. The foci of cellular stratification may lead to consideration of papillary carcinoma; however, the typical nuclear features required to make this diagnosis are not present. These morphologic features reflect the reaction of the thyroid gland to fluctuations of TSH, which is part of the genesis of colloid nodules.

Figure 11.3 Colloid nodules. Bivalved lobectomy with multiple nodules of varying sizes and circumscription in an enlarged gland. |

Figure 11.4 Colloid nodule (Diff-Quick imprint preparation). Abundant background colloid and limited cellular elements similar to FNA features. |

Figure 11.5 Colloid nodule (Diff-Quick imprint). Clusters of cells with oncocytic (Hürthle cell) features. |

While the histologic distinction between an individual colloid nodule and a true follicular neoplasm may be difficult, follicular neoplasms are grossly typically solitary (Figs. 11.1 and 11.7, e-Fig. 11.1). Imprints of follicular neoplasms are cellular showing numerous microfollicles composed of bland to slightly cytologically atypical follicular cells in a background of scant colloid (e-Fig. 11.5). Histologically, peripheral neoplastic

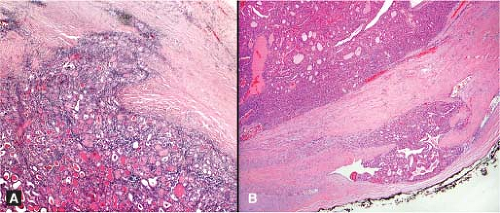

follicles tend to be smaller, more densely packed with scant or absent intraluminal colloid. Since nuclear pleomorphism and atypia are not reliable features of follicular malignancy in the thyroid, the demonstration of capsular and/or vascular invasion are required for a diagnosis of carcinoma (Fig. 11.8). Although this phenomenon is seldom encountered by frozen section, finding it requires a sample from the interface between the capsule and the uninvolved thyroid. In most instances, as recently demonstrated

(17), a frozen section diagnosis of a solitary follicular lesion will be either benign or deferred, with the final diagnosis dependent on a thorough examination of the lesion after appropriate fixation.

follicles tend to be smaller, more densely packed with scant or absent intraluminal colloid. Since nuclear pleomorphism and atypia are not reliable features of follicular malignancy in the thyroid, the demonstration of capsular and/or vascular invasion are required for a diagnosis of carcinoma (Fig. 11.8). Although this phenomenon is seldom encountered by frozen section, finding it requires a sample from the interface between the capsule and the uninvolved thyroid. In most instances, as recently demonstrated

(17), a frozen section diagnosis of a solitary follicular lesion will be either benign or deferred, with the final diagnosis dependent on a thorough examination of the lesion after appropriate fixation.

Figure 11.7 Follicular neoplasm (adenoma): Gross photo of a solitary, circumscribed, and encapsulated mass with central hemorrhage, possibly secondary to prior FNA. |

Figure 11.8 Follicular carcinoma. Partial capsular penetration (A) and vascular invasion (B) rarely encountered in the intraoperative setting. |

From the foregoing, it is apparent that follicular carcinoma is rarely established by frozen section (17,18), supporting those who argue against frozen sections for follicular lesions recognized as such by preoperative FNA. Surgeons who request frozen sections on follicular lesions should understand that follicular neoplasms appearing grossly encapsulated may show only a partially penetrated capsule microscopically and thereby constitute a diagnostic dilemma in the intraoperative setting (Fig. 11.8). Experience suggests that missing an area of vascular invasion is far more likely than recovering it. It is neither practical nor cost effective to submit multiple tissue sections for frozen section study to determine the presence of such invasion. In addition, consideration must be given to the potentially complicating influence of the postfrozen artifacts in the permanent sections. Assuming that the gross differences between follicular adenoma and minimally invasive follicular carcinoma are subtle even under the best of circumstances, the frozen section evaluation of follicular thyroid lesions is likely to fall short of a definitive malignant diagnosis.

Additional confounding factors by frozen section include encapsulated thyroid tumors that exhibit involutional changes or exhibit vascular proliferative changes within the capsular and pericapsular vessels, mimicking vascular invasion. In particular, the various changes associated with FNA-induced or spontaneous bleeding common in colloid nodules can exhibit distention of the vessel lumina by a proliferative cellular infiltrate (15,16). Given the inherent processing difficulties, potential technical artifacts (tissue folds, knife marks, etc.), as well as possible capsular disruption, a diagnosis even on the permanent sections could be significantly compromised.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree