Liver, Extrahepatic Biliary Tree, Gallbladder, and Pancreas

Rish K. Pai

Rebecca Wilcox

Amy Noffsinger

John Hart

Liver

Liver: Major Intraoperative Questions

Frozen sections of the liver are usually performed to evaluate a mass lesion. Frozen sections for the diagnosis of a medical liver condition, such as chronic hepatitis, steatohepatitis, metabolic disorders, or chronic cholestatic conditions, are strongly discouraged. The diagnosis of these latter entities requires excellent slide quality, clinicopathologic correlation, and the use of special stains. Since this is usually not practical in the frozen section suite, the likelihood of diagnostic error is too high to make frozen section evaluation worthwhile in these settings. Moreover, artifactual distortion of the biopsy specimens utilized for frozen section makes this tissue unsuitable for optimal permanent section diagnosis. In any case, the widespread availability of same-day processing of biopsy specimens makes it unnecessary to perform frozen sections on liver biopsies for diagnosis of medical conditions. Of course, there are rare exceptions. For instance, frozen sections are required to evaluate for the presence of microvesicular steatosis by Oil Red O or Sudan Black stain. Also, frozen section analysis of potential donor livers can be essential in predicting the function of the allograft posttransplant.

In contrast, there are many situations in which frozen section evaluation of a mass lesion in the liver is indicated. Surgeons routinely examine the surface of the liver for lesions during abdominal surgery, and, in many cases, an intraoperative ultrasound is performed for suspected deeper lesions. These lesions are commonly submitted for frozen section diagnosis. Occasionally, primary liver tumors are submitted for frozen section diagnosis for histologic confirmation as well as for assessment of the surgical margin. During surgical resections of pancreatic, gastric, and esophageal tumors, the presence of a liver metastasis is a contraindication to resection for cure; thus, the intraoperative consultation directly guides surgical therapy. For colorectal and gynecologic malignancies, finding a small

metastatic tumor deposit in the liver will guide postoperative therapy and does not usually guide intraoperative decision making; nevertheless, surgeons routinely ask for an intraoperative consultation in these cases.

metastatic tumor deposit in the liver will guide postoperative therapy and does not usually guide intraoperative decision making; nevertheless, surgeons routinely ask for an intraoperative consultation in these cases.

Table 13.1 Differential Diagnosis of Mass Lesion in Cirrhotic and Noncirrhotic Livers | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

When reviewing a frozen section on a liver mass, it is essential to know whether the liver is cirrhotic or not, since the differential diagnosis is quite different in these two settings (Table 13.1). For instance, in a noncirrhotic liver, metastatic tumor is always a leading diagnostic consideration while metastatic tumor in cirrhosis is distinctly uncommon. Also, by convention, the diagnosis of hepatic adenoma is not rendered in the setting of cirrhosis.

When performing a frozen section on a small hepatic lesion, it is first important to grossly identify the lesion either visually or with gentle palpation. If no gross lesion is identified, bisecting the tissue may be helpful. When interpreting the frozen section, it is important to keep in mind that the surgeon visualized a lesion; thus, if no mass lesion is evident in the slide, deeper sections should be cut in order to avoid the unpleasant finding

of a worrisome lesion on the permanent sections. Larger lesions should be weighed and the resection margin inked. Since the hepatic capsule does not represent a true oncologic margin, it is not necessary to ink this surface. Serial sections of the specimen should then be performed before selecting the portion of tissue to be frozen.

of a worrisome lesion on the permanent sections. Larger lesions should be weighed and the resection margin inked. Since the hepatic capsule does not represent a true oncologic margin, it is not necessary to ink this surface. Serial sections of the specimen should then be performed before selecting the portion of tissue to be frozen.

If a metabolic disorder is suspected, tissue is snap frozen for possible future enzymatic or genetic testing. However, the first responsibility of the pathologist is to be sure that adequate tissue is reserved for routine H&E examination. If all of the tissue is submitted to rule out a metabolic disorder, and the test is negative, then no diagnosis can be rendered. Tissue for enzymatic or genetic testing should be wrapped in aluminium foil (without OTC) and snap frozen, and then stored at -70°C. It should not be sent for testing until the H&E sections of the other tissue has been examined. Electron microscopy is sometimes helpful in the evaluation of mass lesions, metabolic disorders, and infectious diseases. If a needle core sample is provided, then 1-mm portions from each end of the biopsy can be fixed in glutaraldehyde.

Liver: Frozen Section Interpretation

Metastatic Tumors

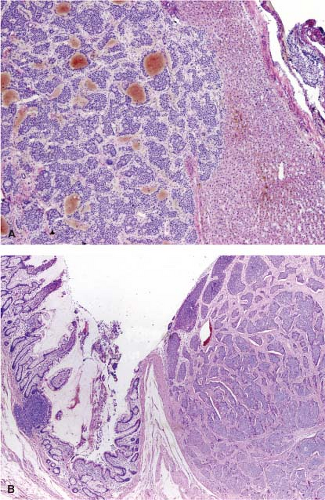

By far, the most common frozen section diagnosis on liver lesions is for metastatic tumor, as the liver is an extremely common site for metastases. Thankfully, the diagnosis of metastatic tumor on a frozen section is usually not difficult. As with other sites of metastasis, desmoplasia is usually very helpful along with the other cytomorphologic features of malignancy (nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, irregular nuclear membranes, atypical mitotic figures, and architectural complexity). Suggesting a source of the primary tumor is not necessary unless asked specifically by the operating surgeon. The exception being a metastatic well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor as its presence should alert the surgeon to look for the primary lesion in the pancreas or small bowel (Fig. 13.1). If the patient has a previous history of a malignancy, review of the prior slides can be extremely helpful.

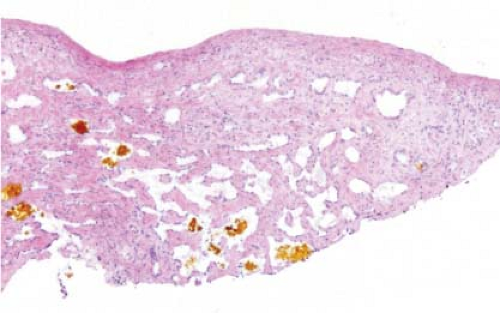

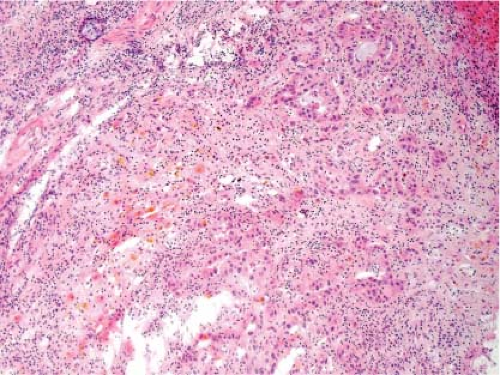

It is not possible to distinguish between primary hepatic cholangiocarcinoma and metastatic adenocarcinoma unless an in situ component can be documented. Colon cancer is the most common metastatic adenocarcinoma, and the presence of tall columnar cells with dirty necrosis is highly suggestive of a colorectal primary (Fig. 13.2). Metastatic pancreatic cancer often induces an exuberant desmoplastic response (Fig. 13.3), although many other tumors such as lung carcinoma can also do this. Gynecologic malignancies have a wide morphologic spectrum, and they can be very difficult to distinguish on a frozen section. A sinusoidal pattern of infiltration by a malignant tumor should suggest the possibility of lymphoma, melanoma, or breast carcinoma. In all cases, if uncertainty exists, it is best to convey that uncertainty to the surgeon and defer a definitive diagnosis until the permanent sections are available.

Bile Duct Hamartoma/Von Meyenburg Complex

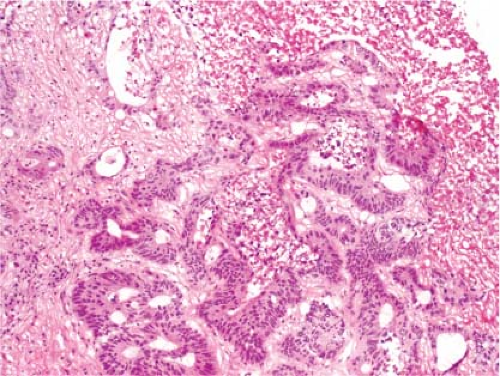

Bile duct hamartomas are the most common diagnoses rendered during frozen section of a liver nodule sampled during abdominal surgery. They are often present just beneath the capsule, and thus are noted by the surgeon. In one autopsy series, bile duct hamartomas were found in 5.6% of individuals (1). Most are less than 5 mm in size. In the majority of cases, distinction between

metastatic carcinoma and bile duct hamartoma is straightforward; however, in one study, bile duct hamartomas were the most common lesion mistaken for metastatic tumor (2). Bile duct hamartomas are well circumscribed, unlike metastatic tumors (Fig. 13.4, e-Fig. 13.1). Moreover, the glandular structures in bile duct hamartomas are lined by cuboidal cells with dilated lumens and rounded contours. Bile or inspissated proteinaceous material can sometimes be present within these lesions. In addition, the stroma surrounding the glands in a bile duct hamartoma is fibrous and quite unlike the desmoplastic stroma seen in metastatic tumors. Distinction between bile duct hamartoma and bile duct adenoma can be difficult at times, but this distinction is of no practical consequence since both lesions are benign and of no clinical significance.

metastatic carcinoma and bile duct hamartoma is straightforward; however, in one study, bile duct hamartomas were the most common lesion mistaken for metastatic tumor (2). Bile duct hamartomas are well circumscribed, unlike metastatic tumors (Fig. 13.4, e-Fig. 13.1). Moreover, the glandular structures in bile duct hamartomas are lined by cuboidal cells with dilated lumens and rounded contours. Bile or inspissated proteinaceous material can sometimes be present within these lesions. In addition, the stroma surrounding the glands in a bile duct hamartoma is fibrous and quite unlike the desmoplastic stroma seen in metastatic tumors. Distinction between bile duct hamartoma and bile duct adenoma can be difficult at times, but this distinction is of no practical consequence since both lesions are benign and of no clinical significance.

Figure 13.2 Metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma. Note the presence of columnar cells with pencillate nuclei and central necrosis. |

Figure 13.3 Metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The desmoplastic stroma is characteristic, but it is not possible to distinguish from a primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. |

Bile Duct Adenoma

Differentiating between bile duct adenomas and metastatic carcinomas can be more challenging. Bile duct adenomas are also fairly small (<1 cm) but can occasionally be quite large (up to 4 cm). They are discovered incidentally during abdominal surgery and are typically subcapsular, circumscribed white-gray firm masses (e-Fig. 13.2). Histologically, they are composed of tightly packed small tubules with scant intervening fibrous stroma (Fig. 13.5, e-Fig. 13.3). At low-power magnification, a bile duct adenoma can closely resemble a metastatic tumor deposit especially when inflamed; however, close inspection reveals glands lined by low-cuboidal epithelium without the histologic features of malignancy (3).

Hepatic Granulomas

On occasion, a frozen section consultation is requested to evaluate a tiny subcapsular nodule to exclude metastatic adenocarcinoma at the time of resection of a gastrointestinal or pancreatic

primary. Often, the sections reveal a bile duct adenoma or bile duct hamartoma, but not infrequently a hyalinized nodule consistent with an old granuloma is identified (e-Figs. 13.4 and 13.5). These granulomas are generally of no clinical consequence, even when there is a small area of central necrosis. If a GMS stain is performed on a permanent section, Histoplasma organisms are sometimes identified, particularly in patients from endemic areas which include the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi river valleys in the United States. Nonetheless, this finding has no bearing on the surgical management of the patient.

primary. Often, the sections reveal a bile duct adenoma or bile duct hamartoma, but not infrequently a hyalinized nodule consistent with an old granuloma is identified (e-Figs. 13.4 and 13.5). These granulomas are generally of no clinical consequence, even when there is a small area of central necrosis. If a GMS stain is performed on a permanent section, Histoplasma organisms are sometimes identified, particularly in patients from endemic areas which include the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi river valleys in the United States. Nonetheless, this finding has no bearing on the surgical management of the patient.

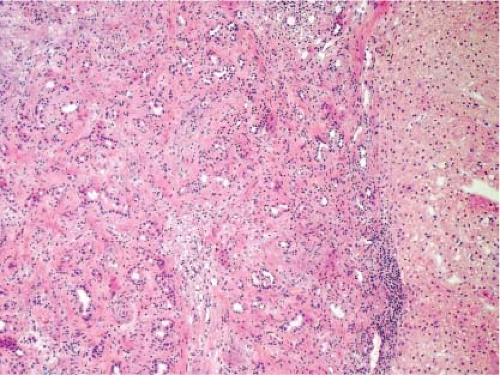

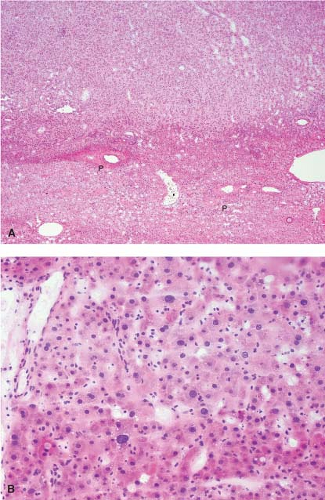

Biliary Obstruction

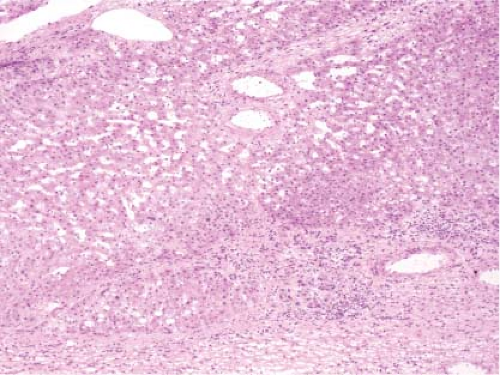

In biliary obstruction caused by pancreatic and common bile duct tumors, numerous small white spots dot the surface of the liver giving the impression to the surgeon of multiple metastatic tumor deposits. A frozen section from these lesions can be quite difficult without complete knowledge of the clinical history particularly when the ductular reaction is florid. The proliferating ductules appear infiltrative and angulated, and a fibrous stromal reaction mimicking a desmoplastic response is also a feature (Fig. 13.6). Recognizing that the proliferating ductules are centered on portal tracts containing portal veins and hepatic artery branches is essential to making this diagnosis.

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), a benign lesion with no risk of malignant degeneration, is sometimes resected to alleviate symptoms. Although FNH occurs in both sexes, these lesions are more common in adult women. Usually, such lesions are more than 10 cm in diameter, and a well-developed central scar containing an anomalous

vessel is evident grossly. FNH is usually circumscribed and paler than the surrounding hepatic parenchyma (Fig. 13.7).

vessel is evident grossly. FNH is usually circumscribed and paler than the surrounding hepatic parenchyma (Fig. 13.7).

FNH can also present as an incidental mass lesion discovered during abdominal surgery. In this setting, the lesion is usually smaller and the central scar may not be grossly evident. In fact, lesions less than 3 cm in diameter usually lack a central scar with a large anomalous vessel. Whether small or large, FNH classically demonstrate three characteristic histologic findings: abnormal lobular architecture, abnormal arteries, and bile ductular proliferation (4). The usual lobular architecture of the liver is disrupted by the presence of thin fibrous septa, which can produce a cirrhosis-like pattern within the lesion. In fact, a clue to the diagnosis of FNH in a needle biopsy is the presence of apparent “cirrhosis,” when in fact the surrounding parenchyma is noncirrhotic. It may even be worthwhile to ask the surgeon to procure a biopsy of the surrounding parenchyma for comparison. The second element of the diagnosis is the presence of abnormal large arteries with intimal proliferation and muscular hypertrophy and a disrupted elastic lamina. The third important component for the diagnosis of FNH is the presence of bile ductules at the periphery of the fibrous septa (Fig. 13.8). Although at first glance, the fibrous septa may appear to represent normal portal tracts, in fact no true native bile ducts are present. Native bile ducts are recognized by their location within the substance of the portal tract (rather than at the interface with the parenchyma), the presence of a normal arteriole of the same caliber nearby (so-called parallelism),

and the presence of a well-formed lumen and surrounding basement membrane. The hepatocytes that make up an FNH are morphologically normal appearing and are arranged in a normal trabecular cord pattern. The hepatocytes near the fibrous septa usually show some evidence of cholate stasis with feathery degeneration, Mallory hyaline, and copper deposition. Steatosis is not uncommon within an FNH. A mild mononuclear cell inflammatory infiltrate is commonly present at the periphery of the fibrous septa along with the proliferating ductules. Needle biopsy frozen section diagnosis of FNH can be challenging, especially without knowledge of clinical impression and radiologic features.

and the presence of a well-formed lumen and surrounding basement membrane. The hepatocytes that make up an FNH are morphologically normal appearing and are arranged in a normal trabecular cord pattern. The hepatocytes near the fibrous septa usually show some evidence of cholate stasis with feathery degeneration, Mallory hyaline, and copper deposition. Steatosis is not uncommon within an FNH. A mild mononuclear cell inflammatory infiltrate is commonly present at the periphery of the fibrous septa along with the proliferating ductules. Needle biopsy frozen section diagnosis of FNH can be challenging, especially without knowledge of clinical impression and radiologic features.

Figure 13.8 Focal nodular hyperplasia. The presence of proliferating bile ductules at the periphery of fibrous septa is characteristic (bottom right). |

As the surgeon usually asks for a frozen section consultation to exclude metastatic tumor, rendering a descriptive frozen section diagnosis stating no evidence of metastatic tumor and deferring further classification of the benign hepatic lesion until the permanent sections is appropriate. Specifically, distinction between FNH and a hepatic adenoma is usually not critical at the time of frozen section consultation if the surgeon is going to perform a complete resection. However, because FNH is benign, resection is not necessary for asymptomatic lesions if a confident frozen section diagnosis is made on a needle biopsy specimen. Likewise, a negative surgical margin is not critical (5).

Hepatic Adenoma

Hepatic adenomas occur only in noncirrhotic livers and never cause an elevation in serum alpha-fetoprotein, two facts that the surgical pathologist should always keep in mind when evaluating a frozen section of a hepatic mass lesion. Large adenomas may cause abdominal pain, while smaller lesions are usually discovered incidentally. Adenomas are much more common in females than males. In fact, the diagnosis of a hepatic adenoma in a male patient who is not taking anabolic steroids should not be made without serious consideration of the possibility of well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (6).

Symptomatic tumors are usually larger than 10 cm in diameter and can be quite a bit larger than that. Adenomas are not encapsulated and are often not well demarcated from the surrounding normal parenchyma. Large adenomas may have large areas of recent and organizing hemorrhage, resulting in a variegated cut surface. Rupture of a very large adenoma through the hepatic capsule can result in catastrophic bleeding, necessitating emergency surgery and a request for a diagnostic frozen section consultation (Fig. 13.9). This dramatic clinical presentation and gross appearance can lead the surgical pathologist to an unwarranted bias toward a malignant diagnosis. Rupture of an adenoma usually occurs in women on oral contraceptives.

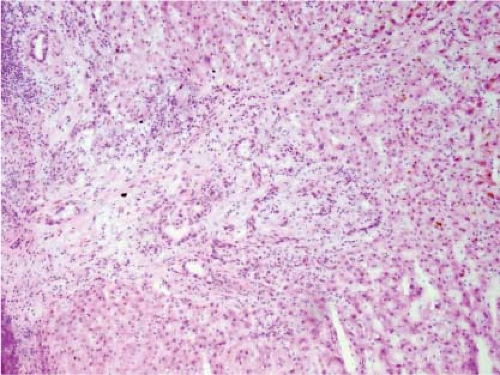

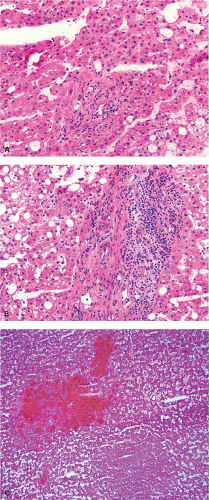

Recently, four molecular and morphologic subtypes of hepatic adenoma have been described: HNF1 A-mutated hepatic adenoma, inflammatory/telangiectatic adenoma, beta-catenin–mutated adenoma, and hepatic adenoma not otherwise specified (7). Of course, subtyping hepatic adenomas at the time of frozen section is not required; however, the inflammatory/telangiectatic variant of hepatic adenoma has some unique

histologic characteristics that warrant mention. Microscopically, adenomas are difficult to distinguish from normal liver and from well-differentiated HCC (6). The key to the distinction from normal liver is the lack of portal tracts within the tumor (Fig. 13.10). One exception is the inflammatory/telangiectatic adenomas which can have portal tract-like structures; however, these portal tract-like structures are often inflamed and contain clusters of arteries rather than an artery and associated bile duct (Fig. 13.11). Adenomas are composed of cytologically bland hepatocytes arranged in the usual pattern of two-cell–thick trabecular cords. Macrovesicular steatosis is common within the tumor especially those with mutations in HNF1 A. Characteristically, there are scattered thin-walled vessels dispersed through the lesion. The fibrous septa with proliferating bile ductules characteristic of FNH are absent in hepatic adenoma although the telangiectatic/inflammatory adenoma may have a subtle ductular reaction at the edge of the portal tract-like structures. Although there may be extensive hemorrhage, necrosis and fibrosis are quite unusual. Mitotic figures should be very rare to absent, but scattered hepatocytes with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei are not uncommon (Fig. 13.10), and should not raise suspicion of HCC. Features that do raise the possibility of well-differentiated HCC include mitotic figures, tumor necrosis, significant increase in nuclear cytoplasmic ratio, and trabecular cords that are more than two to three cells thick. In some cases, it may not be possible to definitely exclude HCC; in such cases, a diagnosis of hepatocellular neoplasm

may be rendered. In most such cases, the surgeon can proceed with the same operation, complete surgical resection of the tumor.

histologic characteristics that warrant mention. Microscopically, adenomas are difficult to distinguish from normal liver and from well-differentiated HCC (6). The key to the distinction from normal liver is the lack of portal tracts within the tumor (Fig. 13.10). One exception is the inflammatory/telangiectatic adenomas which can have portal tract-like structures; however, these portal tract-like structures are often inflamed and contain clusters of arteries rather than an artery and associated bile duct (Fig. 13.11). Adenomas are composed of cytologically bland hepatocytes arranged in the usual pattern of two-cell–thick trabecular cords. Macrovesicular steatosis is common within the tumor especially those with mutations in HNF1 A. Characteristically, there are scattered thin-walled vessels dispersed through the lesion. The fibrous septa with proliferating bile ductules characteristic of FNH are absent in hepatic adenoma although the telangiectatic/inflammatory adenoma may have a subtle ductular reaction at the edge of the portal tract-like structures. Although there may be extensive hemorrhage, necrosis and fibrosis are quite unusual. Mitotic figures should be very rare to absent, but scattered hepatocytes with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei are not uncommon (Fig. 13.10), and should not raise suspicion of HCC. Features that do raise the possibility of well-differentiated HCC include mitotic figures, tumor necrosis, significant increase in nuclear cytoplasmic ratio, and trabecular cords that are more than two to three cells thick. In some cases, it may not be possible to definitely exclude HCC; in such cases, a diagnosis of hepatocellular neoplasm

may be rendered. In most such cases, the surgeon can proceed with the same operation, complete surgical resection of the tumor.

The hepatocytes of an adenoma tend to merge imperceptibly with those of the surrounding parenchyma, making it difficult to evaluate the adequacy of surgical resection (Fig. 13.10, e-Fig. 13.6). The best way to determine the limits of the lesion is to search for portal tracts, which only

occur outside the tumor. Although the surgical aim is always to completely excise the lesion, it is not absolutely critical to do so, since the risk of malignant degeneration is extremely low (8). In rare instances, very large tumors may abut important vascular or biliary structures that make it impossible to completely resect without removal of an unacceptably large portion of the liver.

occur outside the tumor. Although the surgical aim is always to completely excise the lesion, it is not absolutely critical to do so, since the risk of malignant degeneration is extremely low (8). In rare instances, very large tumors may abut important vascular or biliary structures that make it impossible to completely resect without removal of an unacceptably large portion of the liver.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The diagnosis of HCC by frozen section can be quite challenging. These tumors can develop in either a cirrhotic or noncirrhotic setting, but knowledge of the condition of the surrounding parenchyma is still valuable as it influences the differential diagnosis. In a noncirrhotic liver, the distinction between well-differentiated HCC and hepatic adenoma can be extremely problematic. In some cases, only a diagnosis of hepatocellular neoplasm will be possible, as described aforementioned. Fortunately, this is usually the sufficient information for the surgeon to make a decision regarding resection of the mass. On the other hand, in a cirrhotic liver, the problematic distinction is between a well-differentiated HCC and a dysplastic nodule. Again, however, narrowing the differential to these two alternatives is usually adequate for the purposes of surgical management. If the surrounding parenchyma is sampled, the presence or absence of cirrhosis and the degree of macrovesicular steatosis should be made known to the surgeon, since this will influence the decision as to how much of the liver can be resected without threat of postoperative liver failure. The presence of cirrhosis and/or significant macrovesicular steatosis adversely affects the synthetic capacity of the liver, and large resections in the face of these two features can be life threatening, particularly in the elderly or very sick patients. If cirrhosis and/or significant steatosis is present, the surgeon may opt to perform an ablative procedure rather than a resection of the tumor.

The microscopic diagnosis of HCC rests first upon the recognition of hepatocellular origin of the tumor. Most HCCs are composed of large polygonal cells with abundant cytoplasm and a large nucleus containing a

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree