18 Therapeutics and prescriptions

The purpose of drug therapy is to cure or ameliorate disease, or to alleviate symptoms. However, all drugs also have adverse effects and drug therapy is not always necessary. The good prescriber: The good prescriber prescribes only when the balance of benefit to harm is favourable. The choice of drug should be based on an understanding of the relevant pathophysiology and pharmacology, and the dose regimen must take into account the particular circumstances of each patient. The response to treatment should be monitored and the prescription reviewed if adverse effects emerge.

WRITING A DRUG PRESCRIPTION

A prescription should be a precise, accurate, clear, readable set of instructions, sufficient for a nurse to administer a drug accurately in hospital, or for a pharmacist to provide a patient with both the correct drug and the instructions on how to take it. The information that should be written on a prescription is given in Box 18.1. Some abbreviations used in prescribing are listed in Box 18.2. Other abbreviations should be avoided and instructions should, whenever possible, be written in plain English. Because of the problems of drug addiction and misuse of drugs, drugs likely to be abused are, in the UK, the subject of the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971), the Misuse of Drugs (Notification of and Supply to Addicts) Regulations (1973) and the Misuse of Drugs Regulations (1985). The requirements for the prescription of controlled drugs are listed in Box 18.3. Doctors in other countries should make themselves familiar with local regulations.

18.2 ACCEPTABLE ABBREVIATIONS IN PRESCRIPTIONS ![]()

| Abbreviation | Latin meaning | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| b.d. or b.i.d. | Bis in die | Twice a day |

| gutt. | Guttae | Drops |

| i.m. | — | Intramuscular(ly) |

| i.v. | — | Intravenous(ly) |

| o.d. | Omni die | (Once) every day |

| o.m. | Omni mane1 | (Once) every morning |

| o.n. | Omni nocte1 | (Once) every night |

| p.o. | Per os | By mouth |

| PR | Per rectum | By the anal route |

| p.r.n. | Pro re nata | Whenever required |

| PV | Per vaginam | By the vaginal route |

| q.d.s. | Quater die sumendum2 | Four times a day |

| s.c. | — | Subcutaneous(ly) |

| stat. | Statim | Immediately |

| t.d.s. | Ter die sumendum2 | Three times a day |

1 Sometimes written simply as ‘mane’ or ‘nocte’.

2 The abbreviations t.i.d. and q.i.d. (ter/quater in die) are sometimes used instead; do not use q.d. to mean once a day.

ALTERING DOSAGES IN RENAL INSUFFICIENCY

If a drug is more than 50% eliminated unchanged by the kidneys or has active metabolites that are eliminated by the kidneys (Box 18.4), the maintenance dosage must be altered in renal insufficiency, although it is not usually necessary to alter a one-off dose. Creatinine clearance can be used as a guide to reducing maintenance dosages.

18.4 DRUGS WHOSE DOSAGES ARE AFFECTED BY RENAL INSUFFICIENCY1 ![]()

Some drugs should be avoided entirely in renal insufficiency, for either pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic reasons (Box 18.5).

ALTERING DOSAGES IN HEPATIC FAILURE

In contrast to renal insufficiency, there is no easy way of calculating changes in dosage in patients with impaired hepatic function. Dosages of drugs that are metabolised by the liver should therefore be altered according to the therapeutic response, and with careful clinical monitoring for signs of adverse effects.

If a drug has a high rate of hepatic clearance (Box 18.6), it will be mostly cleared during its first passage through the liver (so-called ‘first-pass’ metabolism). In such cases hepatic impairment increases the amount of drug that escapes metabolism in the liver after oral administration, reducing oral dosage requirements but not altering i.v. dosage requirements. The pharmacological effects of some drugs are altered in liver disease, with increased risks of adverse effects (Box 18.7).

18.7 SOME DRUGS WHOSE ACTIONS ARE INCREASEDIN LIVER DISEASE ![]()

| Drug | Adverse effect |

|---|---|

| Oral anticoagulants | Increased anticoagulation (reduced clotting factor synthesis) |

| Metformin | Lactic acidosis |

| Chloramphenicol | Bone marrow suppression |

| NSAIDs | GI bleeding |

| Sulphonylureas | Hypoglycaemia |

ALTERING DOSAGES IN OLDER PEOPLE

Many older people find it difficult to swallow tablets, and the more frail they are, the more difficult this becomes. Tablets or capsules can adhere to the oesophageal mucosa, and tablets should be swilled down with at least 60 ml of water to avoid hold-up.

DRUGS COMMONLY USED FOR INFECTIOUS DISEASES

The optimal selection of antimicrobial therapy requires knowledge of:

ANTIBACTERIAL AGENTS

BETA-LACTAM ANTIBIOTICS (PENICILLINS, CEPHALOSPORINS, CARBAPENEMS)

Mode of action: Exert a bactericidal effect by disrupting bacterial cell wall synthesis.

Penicillins

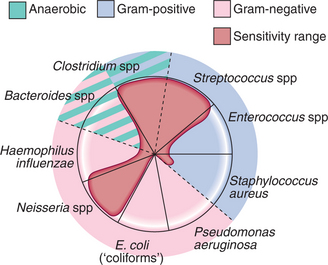

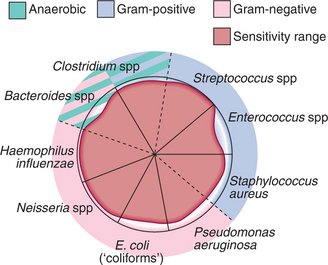

Clinical use: Very cheap, well tolerated, safe and easy to use, but re-sistance is increasing. Natural penicillins are primarily effective against Gram-positive organisms (except staphylococci) and anaerobic organisms (Fig. 18.1).

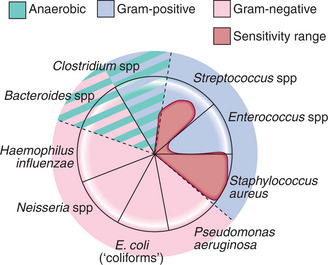

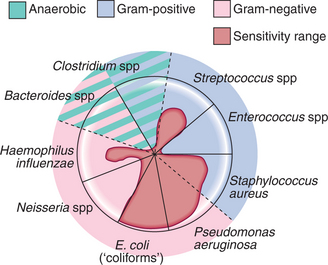

Aminopenicillins have similar activity to natural penicillins with additional Gram-negative cover against Enterobacteriaceae and haemophilus (Fig. 18.3). Addition of the β lactamase inhibitor, clavulanic acid (producing ‘co-amoxiclav’), prevents resistance due to bacterial β-lactamase production and extends the spectrum of activity.

Cephalosporins

Indications: Include sepsis, pneumonia, meningitis, biliary infections, UTIs, peritonitis.

Carbapenems

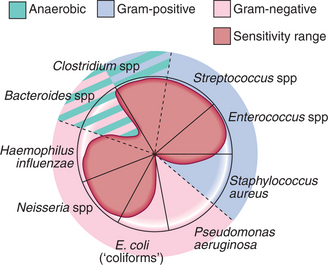

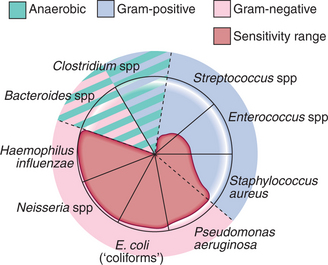

Carbapenems (e.g. meropenem i.v. 500 mg 8-hourly) are very broad-spectrum antibiotics and include activity against anaerobes (Fig. 18.5). They are very expensive, are only available in i.v. formulation, and are reserved for severe infections with organisms resistant to other antibiotics.

MACROLIDES (erythromycin, clarithromycin, arithromycin)

Mode of action: Bind to bacterial ribosomes, preventing protein synthesis.

AMINOGLYCOSIDES (gentamicin, tobramycin)

Mode of action: Bind to ribosomes and interfere with bacterial protein synthesis.

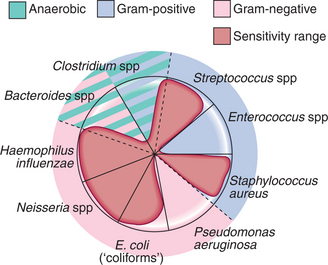

Clinical use: Very effective against Gram-negative organisms (Fig. 18.6), including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and useful in Gram-negative sepsis or serious infections arising from the urinary or biliary tract. They also have some Gram-positive activity and show impressive synergy with penicillins; the combination of gentamicin and penicillin is frequently used in the treatment of endocarditis. They must be administered by injection (e.g. gentamicin i.v./i.m. 3–5 mg/kg 8-hourly), as absorption from the GI tract is negligible. Careful monitoring of renal function and drug levels can help to minimise oto- and nephrotoxicity.

QUINOLONES (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin)

Mode of action: Inhibit bacterial DNA-gyrase, an essential enzyme for DNA replication and repair.

Indications: Infections of the respiratory, urinary and GI tracts; gonorrhoea, anthrax.

Clinical use: Quinolones have very high bio-availability when given by mouth and should only be administered i.v. when the oral route is unavailable.

Ciprofloxacin (oral 250–750 mg 12-hourly; i.v. 200–400 mg 12-hourly) has excellent anti-Gram-negative activity and is also effective against atypical or intracellular organisms, e.g. Mycoplasma and Chlamydia and some Gram-positive organisms (Fig. 18.7). It is used for severe GI infections (e.g. shigellosis, invasive salmonellosis, Campylobacter enteritis) and urinary infections (e.g. acute pyelonephritis, prostatitis, persistent lower UTI).

GLYCOPEPTIDES (vancomycin, teicoplanin)

Mode of action: Inhibit bacterial cell wall synthesis.

Clinical use: Glycopeptides (e.g. vancomycin i.v. 0.5–1 g 12-hourly; teicoplanin i.v./i.m. 200–400 mg daily) are effective against Gram-positive organisms and are particularly useful in infections with MRSA and resistant enterococci, though strains of coagulase-negative staphylococci, enterococci and MRSA resistant to glycopeptides are emerging. Glycopeptides are not active against Gram-negative organisms. Neither drug achieves any useful oral absorption, but oral vancomycin (125 mg 6-hourly for 7–10 days) is effective in diarrhoea due to Cl. difficile infection. The inappropriate use of vancomycin, particularly in the management of Cl. difficile infections (metronidazole is first-line treatment), should be limited to prevent further development of resistance.

FOLATE ANTAGONISTS (trimethoprim)

Indications: UTI, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

TETRACYCLINES (oxytetracycline, doxycycline and minocycline)

NITROIMIDAZOLES (metronidazole)

Oral metronidazole (e.g. 400 mg 8-hourly) is first-line therapy for Cl. difficile infection, bacterial vaginosis, pelvic inflammatory disease (with ofloxacin) and some severe gum and dental infections. I.V. metronidazole (500 mg 8-hourly) is used in patients with sepsis where anaerobic infection is suspected (e.g. post-colonic or pelvic surgery) and, with a broad-spectrum cephalosporin, in peritonitis.

ANTIFUNGAL AGENTS

AZOLE ANTIFUNGALS (clotrimazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole)

Mode of action: Inhibit fungal enzymes necessary for the construction of cell membranes.

DRUGS COMMONLY USED FOR GASTROINTESTINAL DISEASES

ANTACIDS AND ANTISECRETORY DRUGS

H2-RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS (ranitidine)

Indications: Benign gastric or duodenal ulceration, GORD, prophylaxis of acid aspiration in obstetrics and surgery; prophylaxis of stress ulceration in critically ill patients.

PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS (PPIs) (omeprazole, lansoprazole)

Clinical use: PPIs (e.g. omeprazole oral 10–40 mg daily; lansoprazole oral 15–30 mg daily) cause potent acid suppression and rapid ulcer healing, and have become the treatment of choice for many of the above conditions. They form a key component of H. pylori eradication therapy (p. 440) and are effective in both the prevention and treatment of NSAID-associated ulcer. They are superior to H2 antagonists for healing ulcers and oesophagitis. I.V. PPI treatment reduces rates of rebleeding and need for surgery in post-endoscopic therapy for major peptic ulcer haemorrhage, but has not been shown to influence mortality.

ANTIEMETICS

ANTIHISTAMINES (cyclizine, promethazine)

Indications: Nausea, vomiting, motion sickness, vertigo, labyrinthine disorders; also used for the treatment of allergies and urticaria and as an adjunct in anaphylaxis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree