12 Gastrointestinal and nutritional disorders

Diseases of the GI tract are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Approximately 10% of all GP consultations in the UK are for indigestion, and 1 in 14 is for diarrhoea. Infective diarrhoea and malabsorption are responsible for much ill health and many deaths in the developing world.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS

DYSPEPSIA

Dyspepsia (‘indigestion’) may arise from causes within or outside the gut (Box 12.1). Heartburn and other ‘reflux’ symptoms are separate and are considered elsewhere. Although symptoms correlate poorly with diagnosis, careful history may reveal classical symptoms of peptic ulcer, ‘alarm’ features requiring urgent investigation (Box 12.2) or symptoms of other disorders. Dyspepsia affects up to 80% of the population at some time, often with no abnormality on investigation, especially in younger patients.

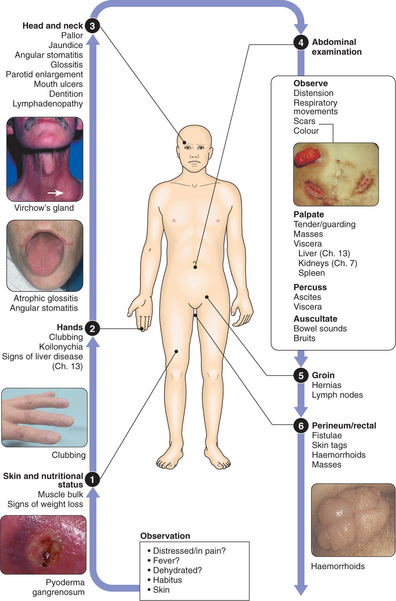

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

VOMITING

The history should reveal associated abdominal pain, fever, diarrhoea, relationship to food, drugs, headache, vertigo and weight loss. Pregnancy, alcoholism or bulimia should be considered. Examination may reveal:

The diagnostic approach will be dictated by the history and examination.

GI BLEEDING

ACUTE UPPER GI HAEMORRHAGE

Haematemesis may be red with clots when bleeding is profuse, or black (‘coffee grounds’) when less severe. Syncope may occur with rapid bleeding. Anaemia suggests chronic bleeding. Melaena is the passage of black, tarry stools containing altered blood. This is usually due to upper GI bleeding, although the ascending colon is occasionally responsible. Severe acute upper GI bleeding occasionally causes maroon or bright red stool. Causes of acute upper GI haemorrhage are shown in Box 12.3.

Management

I.V. access: Should be secured with a large-bore cannula.

Endoscopy: After resuscitation, this will reveal a diagnosis in 80% of cases. Patients with spurting haemorrhage or a visible vessel can be treated by thermal probe, adrenaline (epinephrine) injection or metal clips. This may stop bleeding and, combined with i.v. proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, prevent rebleeding, thus avoiding surgery.

Monitoring: Hourly pulse, BP and urine output.

LOWER GI BLEEDING

This may be due to haemorrhage from the small bowel, colon or anal canal.

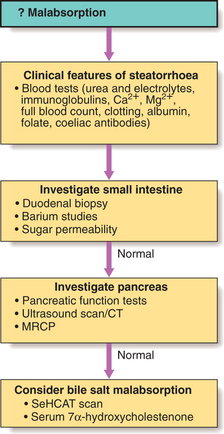

MALABSORPTION

Malabsorption results from abnormalities of the three components of normal digestion:

An approach to investigations is shown in Figure 12.1.

WEIGHT LOSS

History and examination

Systemic diseases: Chronic infections lead to weight loss, and a history of foreign travel, fever, night sweats, rigors, productive cough and dysuria must be sought. Sensitive questions regarding lifestyle (promiscuous sexual activity and drug misuse) may suggest HIV infection. Weight loss is a late feature of disseminated malignancy (carcinoma, lymphoma or other haematological disorders), which may be revealed on examination.

CONSTIPATION

In the absence of a history suggesting a specific cause (Box 12.4), it is not necessary to investigate every person with constipation. Most respond to dietary fibre supplementation and the judicious use of laxatives. Middle-aged or elderly patients with a short history or worrying symptoms (rectal bleeding, pain or weight loss) must be investigated promptly, by either barium enema or colonoscopy. Others should be investigated as follows:

ABDOMINAL PAIN

THE ACUTE ABDOMEN

CHRONIC OR RECURRENT ABDOMINAL PAIN

The choice of investigations depends on the history and examination (Box 12.5). Persistent symptoms require exclusion of colonic or small bowel disease. A history of psychiatric disturbance, repeated negative investigations or vague symptoms not fitting any particular disease or organ pattern may point to a psychological origin.

12.5 INVESTIGATION OF CHRONIC OR RECURRENT ABDOMINAL PAIN ![]()

| Symptom | Probable diagnosis | Investigation |

|---|---|---|

| Epigastric pain; dyspepsia; relationship to food | Gastroduodenal or biliary disease | Endoscopy and USS |

| Altered bowel habit; rectal bleeding; features of obstruction | Colonic disease | Barium enema and sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy |

| Pain provoked by food in widespread atherosclerosis | Mesenteric ischaemia | Mesenteric angiography |

| Upper abdominal pain radiating to the back; history of alcohol misuse; weight loss; diarrhoea | Chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer | USS, CT and pancreatic function tests |

| Recurrent loin or flank pain with urinary symptoms | Renal or ureteric stones | USS and i.v. urography |

DISORDERS OF NUTRITION

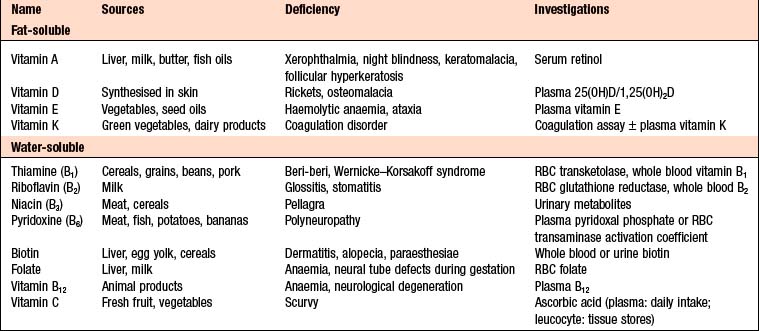

VITAMIN DEFICIENCY

Box 12.6 summarises the sources of vitamins and their deficiency states.

MALNUTRITION

STARVATION AND FAMINE

Decreased energy intake: Causes include:

Increased energy expenditure: Causes include:

Investigations

Management

MALNUTRITION IN HOSPITAL

Nutritional support of the hospital patient

Dietary supplements: If a patient is unable to achieve sufficient nutritional intake from normal diet alone, then liquid dietary supplements with high energy and protein content should be used.

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Anorexia nervosa is a well-defined eating disorder, although a much higher prevalence of abnormal eating behaviour in the population does not meet the diagnostic criteria. There is marked weight loss, arising from food avoidance, in combination with bingeing, purging, excessive exercise, or the use of diuretics and laxatives. Despite their emaciation, patients feel overweight due to body image disturbance. Downy hair (lanugo) develops on the back, forearms and cheeks. Extreme starvation is associated with a range of pathophysiological changes, such as cardiac arrhythmias (prolonged QT and ventricular tachycardia), anaemia and osteoporosis. The condition usually emerges in adolescence, and 90% of cases are female.

Differential diagnosis includes:

OBESITY

Complications of obesity

Health consequences of obesity include:

Obesity has adverse effects on both mortality and morbidity; life expectancy is reduced by 13yrs amongst obese smokers. Coronary heart disease is the major cause of death but cancer rates are also increased.

Clinical features and investigations

Management

Drugs: Drug therapy is usually reserved for obese patients with a high risk of complications. Patients who continue to take anti-obesity drugs tend to regain weight with time. This has led to the recommendation that anti-obesity drugs are used short-term to maximise the weight loss in patients who are demonstrating their adherence to a low calorie diet by current weight loss.

DISEASES OF THE MOUTH AND SALIVARY GLANDS

Parotitis: Due to viral or bacterial infection. Mumps causes a self-limiting acute parotitis. Bacterial parotitis usually occurs as a complication of major surgery and can be avoided by good post-operative care. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are required, whilst surgical drainage is necessary if abscesses are present.

DISEASES OF THE OESOPHAGUS

GASTRO-OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD)

Gastro-oesophageal reflux resulting in heartburn affects ∼30% of the general population.

Clinical features

Complications

Barrett’s oesophagus (‘columnar lined oesophagus’, CLO): A premalignant condition in which the squamous lining of the lower oesophagus is replaced by columnar mucosa with areas of metaplasia. It occurs in response to chronic reflux and is seen in 10% of endoscopies for reflux. The true prevalence may be up to 20 times greater, as it is often asymptomatic or first discovered when the patient develops oesophageal cancer. CLO carries a lifetime risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma of ∼10%. The absolute risk is low and >95% of patients with CLO die of causes other than oesophageal cancer. Prevalence is increasing, especially in white men aged >50. It is weakly associated with smoking but not alcohol. Duodenogastro-oesophageal reflux, containing bile, pancreatic enzymes and pepsin in addition to acid, may be important.

Diagnosis requires multiple biopsies to detect intestinal metaplasia and/or dysplasia.

Investigations

Young patients with typical symptoms of GORD can be treated empirically without investigation.

24-hr pH monitoring: If the diagnosis is unclear after endoscopy or if surgery is considered. Intraluminal pH and symptoms are recorded during normal activities. A pH of <4 for more than 6–7% of the study is diagnostic of reflux.

Management

MOTILITY DISORDERS

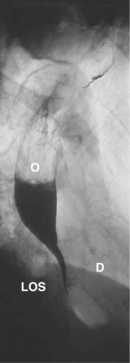

ACHALASIA OF THE OESOPHAGUS

Achalasia is characterised by a hypertonic lower oesophageal sphincter which fails to relax during swallowing and failure of propagated oesophageal contraction, with progressive dilatation. The cause is unknown, although failure of the local nerve supply is implicated. Chagas disease (infestation with Trypanosoma cruzi) is endemic in South America and causes an indistinguishable clinical syndrome (p. 112).

Clinical features and investigations

TUMOURS OF THE OESOPHAGUS

CARCINOMA OF THE OESOPHAGUS

Almost all are adenocarcinoma or squamous cancers. Small-cell cancer is a rare third type.

Clinical features and investigations

Management and prognosis

Approximately 70% of patients have extensive disease at presentation. In these, treatment is palliative and based upon relief of dysphagia and pain. Endoscopic laser ablation or stenting may improve swallowing, while palliative radiotherapy may shrink both squamous cancers and adenocarcinomas.