1 (see

Questions box 15.1

Questions to ask the patient with a rash

It is important to obtain a past history of rashes or allergic reactions. A past history of asthma, eczema or hay fever suggests atopy. Similarly, evidence of systemic disease in the past may be important in a patient with a rash (e.g. diabetes mellitus, connective tissue disease, inflammatory bowel disease).

A detailed social history needs to be obtained regarding occupation and hobbies, as chemical exposure and contact with animals or plants can all induce dermatitis. All medications that have been taken must be documented. Orally ingested or parenteral medications can cause a whole host of cutaneous lesions and can mimic many skin diseases (

TABLE 15.1 Types of cutaneous drug reactions

| 1 Acne, e.g. steroids |

| 2 Hair loss (alopecia), e.g. cancer chemotherapy |

| 3 Pigment alterations: hypomelanosis (e.g. hydroxyquinone, chloroquine, topical steroids), hypermelanosis ( |

| 4 Exfoliative dermatitis or erythroderma ( |

| 5 Urticaria (hives), e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, radiographic dyes, penicillin |

| 6 Maculopapular (morbilliform) eruptions, e.g. ampicillin, allopurinol |

| 7 Photosensitive eruptions, e.g. sulfonamides, sulfonylureas, chlorothiazides, phenothiazines, tetracycline, nalidixic acid, anticonvulsants |

| 8 Drug-induced lupus erythematosus, e.g. procainamide, hydralazine |

| 9 Vasculitis, e.g. propylthiouracil, allopurinol, thiazides, penicillin, phenytoin |

| 10 Skin necrosis, e.g. warfarin |

| 11 Drug-precipitated porphyria, e.g. alcohol, barbiturates, sulfonamides, contraceptive pill |

| 12 Lichenoid eruptions, e.g. gold, antimalarials, beta-blockers |

| 13 Fixed drug eruption, e.g. sulfonamides, tetracycline, phenylbutazone |

| 14 Bullous eruptions, e.g. frusemide, nalidixic acid, penicillamine, clonidine |

| 15 Erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme ( |

| 16 Toxic epidermal necrolysis, e.g. allopurinol, phenytoin, sulfonamides, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| 17 Pruritus ( |

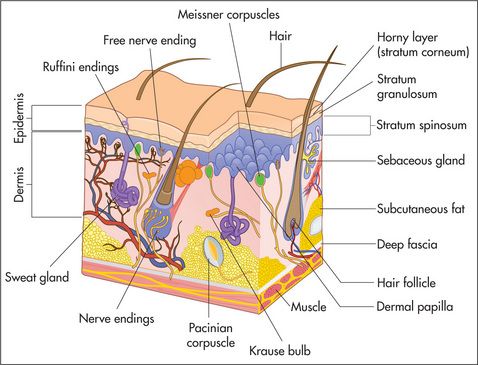

Examination anatomy

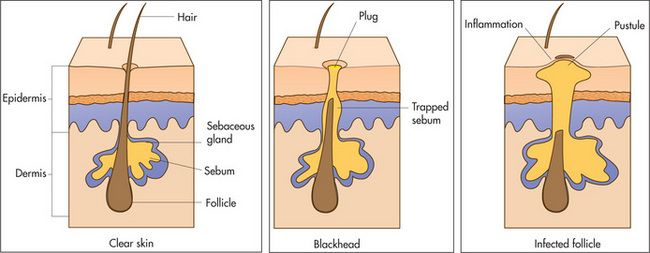

The eccrine glands are present everywhere except in the nail beds and on some mucosal surfaces. They are able to secrete over 5 litres of sweat per day. The apocrine glands are found in association with hair follicles but are confined to certain areas of the body which include the axillae, the pubis, perineum and nipples. They secrete a viscous fluid whose function is unclear in humans.

The nails are formed from heavily keratinised cells that grow from the nail matrix. The matrix grows in a semilunar shape and appears as the lunules in normal finger and toe nails. Hair is also the product of specialised epithelial cells and grows from the hair matrix within the hair follicle.

General principles of physical examination of the skin

The aim of this chapter is to provide an approach to the diagnosis of skin diseases.

Ask the patient to undress. The whole surface of the skin and its appendages should be carefully inspected (

TABLE 15.2 Considerations when examining the skin

| 1 Hair |

| 2 Nails |

| 3 Sebaceous glands—oil-producing and present on the head, neck and back |

| 4 Eccrine glands—sweat-producing and present all over the body |

| 5 Apocrine glands—sweat-producing and present in the axillae and groin |

| 6 Mucosa |

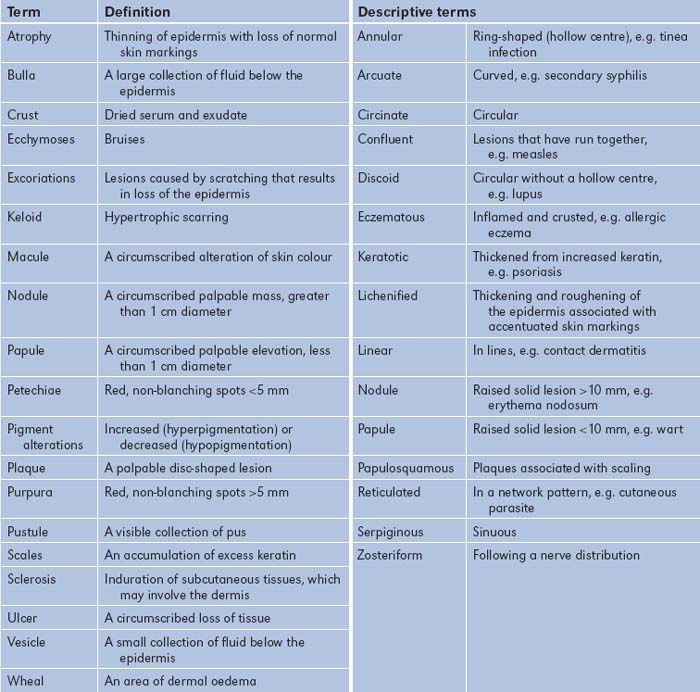

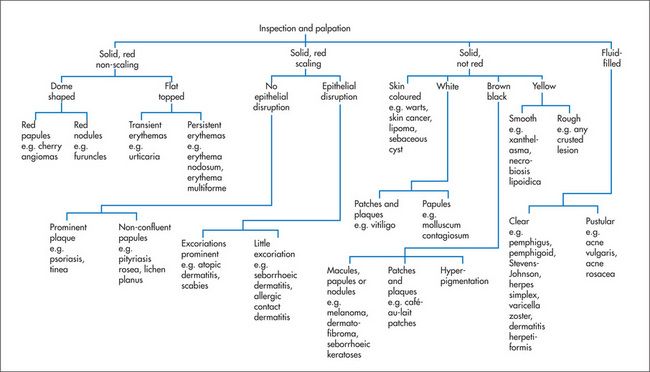

When one is examining actual skin lesions, a number of features should be documented. First, each lesion should be described precisely, including colour and shape. Use the appropriate dermatological terminology (

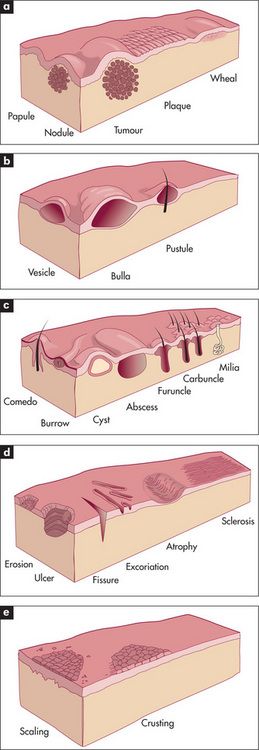

Figure 15.4 Types of skin lesions

(a) Primary skin lesions, palpable with solid mass.

(b) Primary skin lesions, palpable and fluid-filled.

(c) Special primary skin lesions.

(d) Secondary skin lesions, below the skin plane.

(e) Secondary skin lesions, above the skin plane.

Adapted from Schwartz M. Textbook of physical diagnosis, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002.

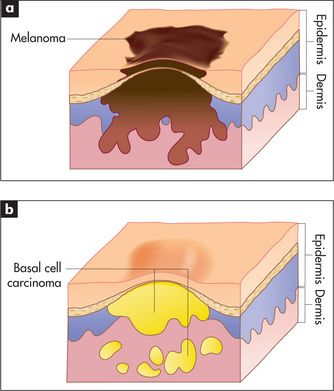

How to approach the clinical diagnosis of a lump

First, determine the lump’s site, size, shape, consistency and tenderness. Next, evaluate in what tissue layer the lump is situated. If it is in the skin (e.g. sebaceous cyst, epidermoid cyst, papilloma), it should move when the skin is moved, but if it is in the subcutaneous tissue (e.g. neurofibroma, lipoma), the skin can be moved over the lump. If it is in the muscle or tendon (e.g. tumour), then contraction of the muscle or tendon will limit the lump’s mobility. If it is in a nerve, pressing on the lump may result in pins and needles being felt in the distribution of the nerve, and the lump cannot be moved in the longitudinal axis but can be moved in the transverse axis. If it is in bone, the lump will be immobile.

Determine if the lump is fluctuant (i.e. contains fluid). Place one forefinger (the ‘watch’ finger) halfway between the centre and periphery of the lump. The forefinger from the other hand (the ‘displacing’ finger) is placed diagonally opposite the ‘watch’ finger at an equal distance from the centre of the lump. Press with the displacing finger and keep the watching finger still. If the lump contains fluid, the watching finger will be displaced in both axes of the lump (i.e. fluctuation is present).

Place a small torch behind the lump to determine whether it can be transilluminated.

Note any associated signs of inflammation (i.e. heat, redness, tenderness and swelling

Look for similar lumps elsewhere, such as multiple subcutaneous swellings from neurofibromas or lipomas. Neurofibromas are smaller than lipomas. They look hard but are remarkably soft; they occur in neurofibromatosis Type 1 (von Recklinghausen’s

If an inflammatory or neoplastic lump is suspected, remember always to examine the regional lymphatic field and the other lymph node groups.

Correlation of physical signs and skin disease

There are many different skin diseases with varied physical signs. With each major sign the groups of common important diseases that should be considered will be listed.

Pruritus

Pruritus simply means itching. It may be either generalised or localised. Scratch marks are usually present. Localised pruritus is usually caused by a dermatological condition such as dermatitis or eczema. Generalised pruritus may be caused by primary skin disease, systemic disease or psychogenic factors.

To determine the cause of the pruritus it is essential to examine the skin in detail (

TABLE 15.4 Primary skin disorders causing pruritus

| 1 Asteatosis (dry skin) |

| 2 Atopic dermatitis (erythematous, oedematous papular patches on head, neck, flexural surfaces) |

| 3 Urticaria |

| 4 Scabies |

| 5 Dermatitis herpetiformis |

When primary skin diseases have been excluded, a detailed history and examination should be undertaken to consider the various systemic diseases listed in

TABLE 15.5 Systemic conditions causing pruritus

| 1 Cholestasis, e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis |

| 2 Chronic renal failure |

| 3 Pregnancy |

| 4 Lymphoma and other internal malignancies |

| 5 Iron deficiency, polycythaemia rubra vera |

| 6 Endocrine diseases, e.g. diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, carcinoid syndrome |

Erythrosquamous eruptions

Erythrosquamous eruptions are made up of lesions that are red and scaly. They may be well demarcated or have diffuse borders. They may be itchy or asymptomatic.

When one is attempting to establish a diagnosis of an erythrosquamous eruption, the history is very important. First ask about the time course of the eruption, about a family history of similar skin diseases and whether or not there is a family history of atopy.

The presence or absence of itching and the distribution of the lesions (often on the extensor surfaces of the limbs) also give clues about the diagnosis.

Asymptomatic lesions on the palms and soles are suggestive of secondary syphilis, whereas itchy lesions in the same location would be more suggestive of lichen planus (

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree